|

Where You Live:

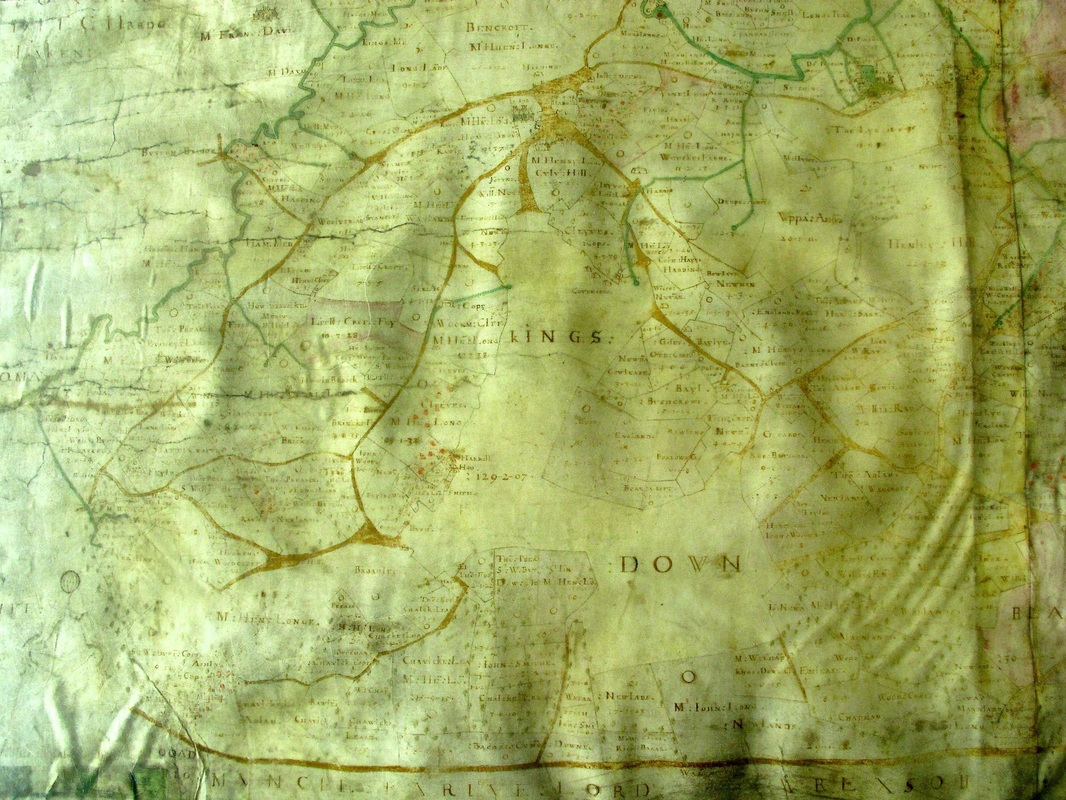

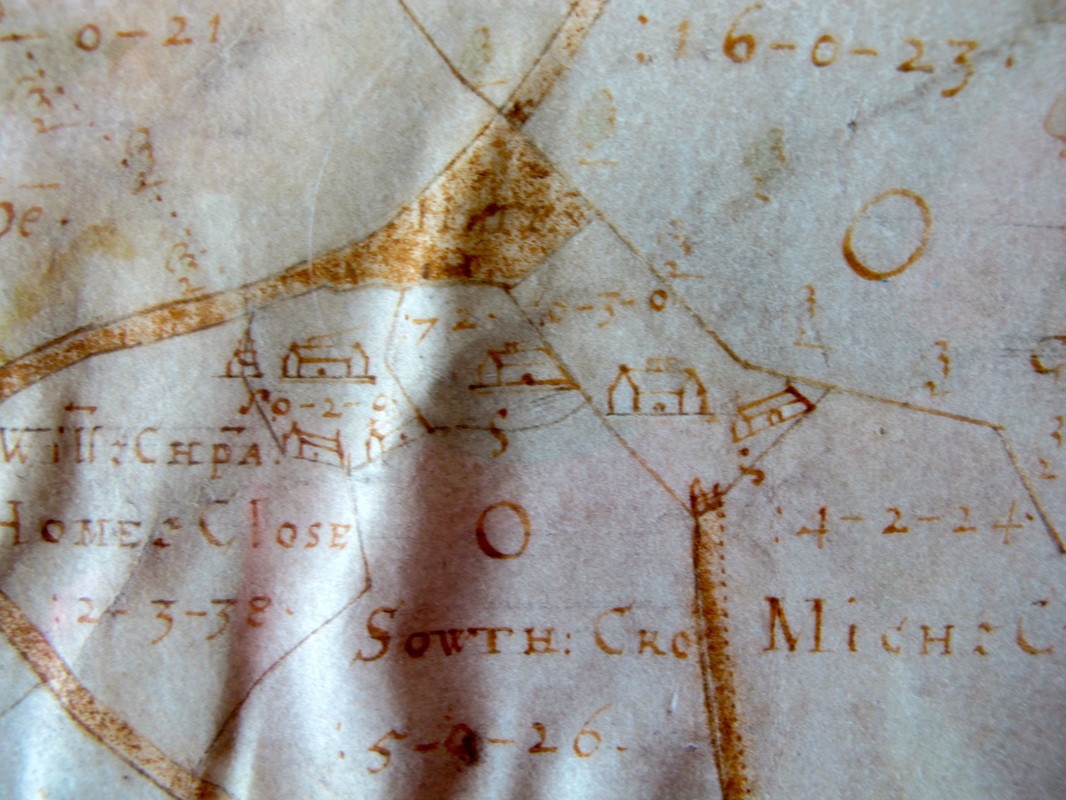

What Was There in 1626? Alan Payne October 2015 Francis Allen’s map of The Mannors of Haiselbury, Box and Ditchridge is full of wonderfully intricate drawings of houses, natural features, roads and information about the usage of individual fields. All map extracts are courtesy of Wiltshire History Centre. Click on headings or maps to enlarge the images and find out more about the area. Please contact us if you are able to add to this information. |

|

Featured Below are the Following Areas

Central Box Ashley Ditteridge Middlehill Rudloe |

Kingsdown Hazelbury and Box Fields Hatt, Old Jockey and Blue Vein Henley |

Please click on blue headings below for the hamlets to access more maps and details about individual areas.

The Allen Maps

These maps come in different forms: a black-and-white version re-drawn in 1907 which carries the date 1630 (below right); and a coloured version dated 1626 which appears to be the original pictorial view of the area (below left).The maps were functional documents, made to record the estate, one apparently on the death of Hugh Speke and the transfer of the estate to his son George in 1624.[1] It was a new science because modern map surveying only begun about 1580 and the first Ordnance Survey not until 1749.

We don't know how many legal properties existed in the village at this time but we might guess that the population of the parish was about 300 households in 1600 (perhaps 700 adults) rising to about 400 households in 1650. What the map does not show are the squatters and migrants who set up on wasteland and common land. Allen records none of these dwellings which were part of a black-market vagrant class.

These maps come in different forms: a black-and-white version re-drawn in 1907 which carries the date 1630 (below right); and a coloured version dated 1626 which appears to be the original pictorial view of the area (below left).The maps were functional documents, made to record the estate, one apparently on the death of Hugh Speke and the transfer of the estate to his son George in 1624.[1] It was a new science because modern map surveying only begun about 1580 and the first Ordnance Survey not until 1749.

We don't know how many legal properties existed in the village at this time but we might guess that the population of the parish was about 300 households in 1600 (perhaps 700 adults) rising to about 400 households in 1650. What the map does not show are the squatters and migrants who set up on wasteland and common land. Allen records none of these dwellings which were part of a black-market vagrant class.

Farming Everywhere

There are all sorts of residences from the grand manor houses dealt with in a separate article to small cottages. Numerous elegant farmhouses are shown which still give character and style to most of the hamlets in Box. Many were built of local stone (at first rubble and later ashlar blocks). They form part of a vernacular style of architecture which characterises the area.

The map shows that Box was mostly composed of small fields (10 to 20 acres). Many of the enclosed fields and their cottage were suitable for subsistence farming, vital for the survival of the tenant both self-employed and wage-earners. Most farmhouses built at this time were of rubble stone with coped gable ends (overhanging roof on side walls) to give extra support to the rubble walls rather than hipped roofs (pyramid shaped). Most had thatch roofs, only a few could afford stone tiles, with smaller tiles at the ridge to enable the pitch of the roofs to be steeper to throw off water. The windows were mullioned (with vertical central support) and made in stone.

New farmhouses were built in outlying blocks of land as part of a complex of farm buildings centred on a farmyard. They were part of a self supporting agricultural unit which is sometimes called horn and corn.[2] Corn was grown to provide fodder as grain and straw; horned cattle and sheep provided hides, wool, meat, tallow, milk and cheese; the dairy waste fed pigs. The animal excrement produced manure to put back on the land to fertilise it. The farmsteads were ideal for family tenants who concentrated on selling butter, cheese and pigs who lived on milk whey. Sheep dominated the steep hillsides and provided wool and skins.

The farmsteads were arranged around a yard often flanked on three or four sides by buildings providing specific services: corn store and threshing barns; livestock sheds and dung storage; wagon-house and implement sheds; and the farmhouse and dairy buildings.[3] The design was primarily to reduce labour in handling the volume of animal feed and waste excrement by reducing unnecessary movement and cleaning. Manure was stored on site with a minimum of cleaning down before recycling onto outlying fields as manure.[4]

The enclosed farmyard enabled better control of young calves and easier milking than open fields. The yards often faced south to catch the sun and avoid rain from the south-west; horse sheds faced east for the early morning sunrise; and implement barns faced north to avoid the wood drying out in the sunshine. Pigs were housed near the farmhouse and dairy.

The prosperity of these tenant farmers was often reflected in new buildings they constructed on the family farm, including barns, granaries, stables, cowhouses and pigsties. Barns were the largest building, usually with a large entrance for carts, ventilation holes to stop overheating, and holes to let in barn owls to kill sparrows and rodents.[5]

There are all sorts of residences from the grand manor houses dealt with in a separate article to small cottages. Numerous elegant farmhouses are shown which still give character and style to most of the hamlets in Box. Many were built of local stone (at first rubble and later ashlar blocks). They form part of a vernacular style of architecture which characterises the area.

The map shows that Box was mostly composed of small fields (10 to 20 acres). Many of the enclosed fields and their cottage were suitable for subsistence farming, vital for the survival of the tenant both self-employed and wage-earners. Most farmhouses built at this time were of rubble stone with coped gable ends (overhanging roof on side walls) to give extra support to the rubble walls rather than hipped roofs (pyramid shaped). Most had thatch roofs, only a few could afford stone tiles, with smaller tiles at the ridge to enable the pitch of the roofs to be steeper to throw off water. The windows were mullioned (with vertical central support) and made in stone.

New farmhouses were built in outlying blocks of land as part of a complex of farm buildings centred on a farmyard. They were part of a self supporting agricultural unit which is sometimes called horn and corn.[2] Corn was grown to provide fodder as grain and straw; horned cattle and sheep provided hides, wool, meat, tallow, milk and cheese; the dairy waste fed pigs. The animal excrement produced manure to put back on the land to fertilise it. The farmsteads were ideal for family tenants who concentrated on selling butter, cheese and pigs who lived on milk whey. Sheep dominated the steep hillsides and provided wool and skins.

The farmsteads were arranged around a yard often flanked on three or four sides by buildings providing specific services: corn store and threshing barns; livestock sheds and dung storage; wagon-house and implement sheds; and the farmhouse and dairy buildings.[3] The design was primarily to reduce labour in handling the volume of animal feed and waste excrement by reducing unnecessary movement and cleaning. Manure was stored on site with a minimum of cleaning down before recycling onto outlying fields as manure.[4]

The enclosed farmyard enabled better control of young calves and easier milking than open fields. The yards often faced south to catch the sun and avoid rain from the south-west; horse sheds faced east for the early morning sunrise; and implement barns faced north to avoid the wood drying out in the sunshine. Pigs were housed near the farmhouse and dairy.

The prosperity of these tenant farmers was often reflected in new buildings they constructed on the family farm, including barns, granaries, stables, cowhouses and pigsties. Barns were the largest building, usually with a large entrance for carts, ventilation holes to stop overheating, and holes to let in barn owls to kill sparrows and rodents.[5]

Agricultural Cottages

The number of cottages built or rebuilt in the 1600s in the outlying hamlets is astounding. There are 60 properties surviving as Listed Buildings in the parish identified to this period. Most replaced medieval cottages but some were new-builds to satisfy rising population numbers. Most of these properties are built in a similar style: rubble, thatch or stone tiled roofs and gable ends.

It is noticeable that in some areas fields on Allen’s map were called croft or close: Slade Croft, Sharp Croft, Alley Croft, and Al Croft. These refer to smaller areas of land which had been enclosed usually at the perimeter of the common arable fields or woodland. They usually had a cottage or house.[6]

At the bottom of the ladder were tenant labourers living in shacks, squatting on wasteland or wooded areas, or living rough. surviving on subsistence wages in the good years and outdoor poor relief in the times of bad harvests. These people had little or no means of supporting themselves in the worst times and required the communal support of the parish.

The number of cottages built or rebuilt in the 1600s in the outlying hamlets is astounding. There are 60 properties surviving as Listed Buildings in the parish identified to this period. Most replaced medieval cottages but some were new-builds to satisfy rising population numbers. Most of these properties are built in a similar style: rubble, thatch or stone tiled roofs and gable ends.

It is noticeable that in some areas fields on Allen’s map were called croft or close: Slade Croft, Sharp Croft, Alley Croft, and Al Croft. These refer to smaller areas of land which had been enclosed usually at the perimeter of the common arable fields or woodland. They usually had a cottage or house.[6]

At the bottom of the ladder were tenant labourers living in shacks, squatting on wasteland or wooded areas, or living rough. surviving on subsistence wages in the good years and outdoor poor relief in the times of bad harvests. These people had little or no means of supporting themselves in the worst times and required the communal support of the parish.

|

The centre of the village is dominated by two buildings:

the church and the Manor House. The church is not dissimilar to the present building in layout. It was obviously the centre of many village activities with about a dozen buildings surrounding it. One field to the west is called Vicre Ground and one to the east is Parson. Water has been diverted from the By Brook towards the church and to a large mill pond at the building now called The Wilderness. The mill building may be that shown on the map. The diversions may also have served to try to drain the field to the west named Stickings. |

What is not shown is also significant. This was a pre-urbanised village before the central developments of the Victorian period. There are only a few properties on the modern High Street. One is in the right place for the Bear Inn and another about where Queen's Square now stands. Nor is there any evidence of Balaam's Passage or a route to Monkton Farleigh. Properties do not become apparent until the area of land controlled by Manor House Farm.

|

The Ashley area of the 1626 map focusses on two things: Ashley Manor House and evidence of field strips and small enclosures of land, some called crofts, left over from Saxon times.[7]

The area between the south side of Ashley Lane (the top track running east-west) and Wormcliffe Lane (the bottom track) has been extensively developed (for the time) with several properties shown at Ashley Grove. Although it is not totally clear, the property at the village end of Ashley Lane appears to be Spencer's Farmhouse. The property at the bottom right is considered to be an early image of Kingsdown House. |

Other properties on Ashley Lane date from later than 1626. Sheylor’s Farmhouse has a magnificent seven-bay barn from the late 1600s with a stone tiled roof, matching the splendour of the farmhouse.[8] The barn at Ashley Farmhouse has a dovecote over the cart-entry.[9] Until the early 1600s only the Lord of the Manor was allowed to keep doves and pigeons without permission, which indicates later date. Pigeons were an important source of meat and eggs and their droppings were useful to make fertiliser and saltpetre. By the middle of the century manor houses often had provision for doves and pigeons and gradually this spread to farmhouses and even humble cottages. The 1630 map identifies the field to the south of Ashley Manor House as Culverhaie, referring to doves bred for food, which appears as Cvlv Hill in the 1626 map.

Ditteridge

The hamlet of Ditteridge still carries its history in its field names and other topography. In the 1630 map the area was dominated by Saxon open fields for the agricultural use of the commoners of the area: Dichridg Uppar Feilde and Low Feilde.

Ditteridge

The hamlet of Ditteridge still carries its history in its field names and other topography. In the 1630 map the area was dominated by Saxon open fields for the agricultural use of the commoners of the area: Dichridg Uppar Feilde and Low Feilde.

The area also shows its medieval history with fields called Newlandes and Ingrove names referring to wasteland around the open fields which were taken into cultivation at times of population pressure before the Black Death of 1348. The shape of the properties and their gardens south of the church are not typical of medieval or Tudor enclosures. Indeed, they have the small, thin shape of Saxon homes, gathered together for safety and using the nearby common fields for joint farming purposes.

The area is dotted in red. It is not clear what this means at first and you would be forgiven for thinking they are trees or shrubs.

There are fields with tree names: Perry Croft refers to pear trees grown for food and timber.[10] There is a field called Crabtree Mead on the banks of the River Lid, appearing to be an enclosure of Ditteridge Lower Field.

But the red dots are more likely to differentiate land paying tithe dues to Ditteridge Church rather than the unmarked land which related to Box Church. This would be of vital interest to the Speke family as they were obliged to collect tithes from tenants and to pay the relevant parochial council.

The area is dotted in red. It is not clear what this means at first and you would be forgiven for thinking they are trees or shrubs.

There are fields with tree names: Perry Croft refers to pear trees grown for food and timber.[10] There is a field called Crabtree Mead on the banks of the River Lid, appearing to be an enclosure of Ditteridge Lower Field.

But the red dots are more likely to differentiate land paying tithe dues to Ditteridge Church rather than the unmarked land which related to Box Church. This would be of vital interest to the Speke family as they were obliged to collect tithes from tenants and to pay the relevant parochial council.

There is an interesting error in the 1907 transcription of the 1630 map. Muttõ Lay (still called Mutton Field) refers to sheep farming, whereas the transcription incorrectly shows Multo Lay.

|

Middlehill

Various fields in Middlehill also appear marked with red dots indicating that their tithe was due to Ditteridge Church, not Box. One significant tree - almost a tree of life - was shown growing isolated in a field (shown bottom left). We known of no reason for this and any suggestions would be appreciated. Although the area is so close to Box village, it was largely without residences. Two fields called Gleeb were the private lands of rector of St Christopher's. One of the glebe fields is specifically marked as an orchard. There are several properties marked and one, probably Toad Hall, was a grand house with ashlar walls and an expensive mansard (4-sided hip) roof. |

We might think that the area was comparatively empty of properties because of the steep hill and the inconvenience of the road infrastructure before the 1840s road was built going north from the A4. But it was also a deliberate policy of the village authorities. Squatters who built on common land were evicted unmercifully.

In 1603 the Chippenham Justices of the Peace refused permission for one cottage house within the Comon of Mydlehill built by Anthony Jones and presented Johane (Joanne) Keynes, widow, for living in a small cottage house in Hatt, as it did not have two hectares of land attached.[11] The justices were frightened that squatter communities would grow up around central Box as they had at Warminster and Broughton Gifford.

In 1603 the Chippenham Justices of the Peace refused permission for one cottage house within the Comon of Mydlehill built by Anthony Jones and presented Johane (Joanne) Keynes, widow, for living in a small cottage house in Hatt, as it did not have two hectares of land attached.[11] The justices were frightened that squatter communities would grow up around central Box as they had at Warminster and Broughton Gifford.

|

Rudloe

We have quite a lot of information about Tudor Rudloe. In 1533 Robert Leversage, Esq of Frowmselwood, Somerset owned the manor of Rudlowe in Box parish and 8 messuages, 100 aces of pasture, 50 acres of meadow, 300 acres of arable land, 20 acres of wood, and 40 acres of gorse and heath in Rudlowe and Boxe, worth £10 yearly.[12] Robert had over-reached his wealth. In March 1533 he was in default of a debt of 500 marks (£333) owed to William Button (executor of William Button, gentleman, of Alton) and the sheriff was ordered to seize his property. He was subject to other litigation because a year later he was sued by William Dauntsey over land in Stokton.[13] |

The family retained their estate, however, because in 1568 it was owned by a person called Edmund Leversege.[14]

|

Kingsdown

Allen's 1626 map is badly faded at the Kingsdown area but it is still possible to piece together the history of the area. The area is a large open grassland for the use of the commoners who lived nearby. What we don't see is the pronounced east-west route through the downland, that dominates the passage through the golf course today. We know that the medieval Old Bath Road went through Kingsdown but we should not think of this route as a modern road. Rather, it was more like an area of trackway, often extremely wide where animals and people chose the best path for the time of year. |

|

There is a better view of the area in the 1630 map. We can see that there had been considerable enclosure surrounding the common land at Kingsdown with small fields called New Close, Burrow Croft (referring to rabbit farming), Wan Croft and Hooke Croft. The modern name of Closes Farm still recalls the enclosure movement needed for animal husbandry.

Even by the time of Allen's map, common land clearly had been much larger than it was in the early 1600s with field names of Comon Dowe, New Landes and Innox all shown as closes off the main commonland to the south of Kingsdown Common. |

There are one or two references to quarrying in the area, notably two separate fields called Cleeves. But this period was long before the quarry trade mushroomed with heavy lifting equipment and railways to transport the stone.

|

Hazelbury and Box Fields

Allen's map was drawn to record the extent of the Speke estate in Box. Little wonder that Hazelbury Manor is drawn so carefully and in so much detail. The house is shown on the 1630 map as surrounded by a warren. There are other references in this area; Coneger (an enbanked enclosure warren) at Fiveways was for the breeding of young rabbits. It was a very valuable resource and on his death Sir John Young left to his wife, Joan, his mansion at Hazelbury and the rabbit warren there, allowing her: two hundrethe cupple of connies yearlie to be taken uppon the warren groundes there to her said use at such time as she shall require the same.[15] |

|

It is evident that the old Saxon common field (Box Feilde) was within the authority of the lord of the manor. The maps show the fields running off the Hazelbury lands. The common land, however, had reduced to just 130 acres and only in isolated pockets. Some of the enclosure is marked as general Quare (quarry); others are specified as The Tile Pitte Feilde.

Marked in the middle of one of the common fields is Owld Church, the remains of the Hazelbury church which is situated close to inter-connecting tracks through the fields and may have originally been a field cross church. The church is reputed to have become deserted after the Black Death of 1348 had significantly affected the Hazelbury area. |

Around Box Fields are closes called Feilde Close, West Croft, Twelve Acres, Long Croft and Tile Pitte Closes; and In the woodland areas are enclosures called Wood Croftes, Log Croft and South Croft.

|

Hatt, Old Jockey and Blue Vein

This area was much more important in Tudor and Stuart times than it is today because it was on the old medieval road from London to Bath and Bristol. In Allen's time it was used by foot travellers, horse-riders and drovers herding flocks of cows, pigs and sheep from Wales to London. In the early Georgian period carriages and stage coaches became more common. And later the road was by-passed by the A4 route through Box and the building of the Devizes Road, both paid for by toll trusts.The area was (and is) deeply rural. Leuertes at Hatt is a reference to leverets (young rabbit). |

With these developments horses became more common. Horse stables usually had mangers with a hayloft above for pitching hay down through square pitching holes. Old Jockey Farmhouse has a horse barn with hayloft and racks. A number of old agricultural cottages were converted into farms, including Old Jockey and Blue Vein Cottage which originally had a thatch roof and later became sufficiently wealthy to have a slate roof.[16]

|

Henley and Washwells

A barn at Henley has a medieval window incorporated into a later building of the 1700s.[17] The cultivation of the village was limited by the steep valley inclines. At Henley, timber cultivation largely replaced animal husbandry. The coppicing fields include Whit Wood shown as a plantation, and the forestation continues up the hill with Stake Leases and Hat Copp(ic)e for the coppicing of wood for kindling and fencing needs by removing the main stem of the tree and harvesting young growth from the stump.[18] Woodland areas were an important part of the economy for centuries and the king kept his rights over Chippenham Forest up until 1618.[19] |

Other animals too are mentioned. Other fields refer to more usual animal husbandry. Stey Feilde at Middlehill and Swine Leyes at Hazelbury refer to out-pasture for pigs, possibly where the animals were once allowed to root free in woodland.

Your Views

Can you add to the information with detailed knowledge of your area? Do you disagree with any of the comments?

We welcome your contributions to get better accuracy, particlularly where there is so little documentary evidence.

If your area hasn't been mentioned, you can write to us via the Contact tab and we will do our best to bring it into the spotlight.

Can you add to the information with detailed knowledge of your area? Do you disagree with any of the comments?

We welcome your contributions to get better accuracy, particlularly where there is so little documentary evidence.

If your area hasn't been mentioned, you can write to us via the Contact tab and we will do our best to bring it into the spotlight.

References

[1] The map was redrawn in 1907 by Thomas Holloway, Surveyor in Chippenham. This version is available at the Wiltshire History Centre, Chippenham.

[2] Jeremy Lake, Historic Farm Buildings, 1989, Blandford Press, p.16

[3] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, 1970, David & Charles, p.77-79

[4] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, p.76

[5] Jeremy Lake, Historic Farm Buildings, p.20

[6] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.20

[7] See Tudor and Stuart Mansions for Ashley Manor House

[8] See Historic Buildings

[9] See Historic Buildings

[10] John Field, A History of English Field-names, p.66

[11] BH Cunniston, Records of the County of Wilts, 1932, Devizes, p.5

[12] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol. XXVIII

[13] The National Archives DD\BR\Wt/11

[14] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, edited by Canon Jackson, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.56

[15] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 57, p.293

[16] Katherine Harris, papers in Wiltshire History Centre

[17] See Historic Buildings

[18] John Field, A History of English Field-names, p.55

[19] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.413

[1] The map was redrawn in 1907 by Thomas Holloway, Surveyor in Chippenham. This version is available at the Wiltshire History Centre, Chippenham.

[2] Jeremy Lake, Historic Farm Buildings, 1989, Blandford Press, p.16

[3] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, 1970, David & Charles, p.77-79

[4] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, p.76

[5] Jeremy Lake, Historic Farm Buildings, p.20

[6] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.20

[7] See Tudor and Stuart Mansions for Ashley Manor House

[8] See Historic Buildings

[9] See Historic Buildings

[10] John Field, A History of English Field-names, p.66

[11] BH Cunniston, Records of the County of Wilts, 1932, Devizes, p.5

[12] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol. XXVIII

[13] The National Archives DD\BR\Wt/11

[14] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, edited by Canon Jackson, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.56

[15] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 57, p.293

[16] Katherine Harris, papers in Wiltshire History Centre

[17] See Historic Buildings

[18] John Field, A History of English Field-names, p.55

[19] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.413