Box Church and Farleigh Priory Alan Payne October 2023

Origins of Box Church

The origins of Box Church are shrouded in uncertainty. The only reference seems to be John Aubrey’s assertion that

Parson Bridges says Sir Hugh Speke told him that he had searched in the Black Book and found …. That 100 years after the conquest Box church was built by the Earl of Hereford (the Bohun family).[1] In John Edward Jackson’s commentary, he wondered if the real builders were the Bigod family and a plaque in the church’s north aisle says This church was first built in 1200s.

The consensus seems to be that it was built by the lords of the manor around the end of the 12th century.

The location of the building is problematic - at the bottom of a slope and isolated from the residents in the Market Place. It could have been positioned as the Bigods’ private chapel (but we do not know where their Manor House or Hall was situated). Alternatively, like many other Wiltshire churches, it could have been sited close to the Roman Villa, a place of ancient significance, where it inherited the greatness of the ancient Romans and where stone could be plundered.[2] The early stone building was a simple rectangular shape, comprising a nave for laymen and a chancel for the priest, which possibly doubled as the vicar’s accommodation.[3] It was just such a building that William of Malmesbury described in 1125 as Churches rise in every village,[4] mass-produced buildings, thrown up quickly as were hundreds of others in the period before 1150.[5]

The origins of Box Church are shrouded in uncertainty. The only reference seems to be John Aubrey’s assertion that

Parson Bridges says Sir Hugh Speke told him that he had searched in the Black Book and found …. That 100 years after the conquest Box church was built by the Earl of Hereford (the Bohun family).[1] In John Edward Jackson’s commentary, he wondered if the real builders were the Bigod family and a plaque in the church’s north aisle says This church was first built in 1200s.

The consensus seems to be that it was built by the lords of the manor around the end of the 12th century.

The location of the building is problematic - at the bottom of a slope and isolated from the residents in the Market Place. It could have been positioned as the Bigods’ private chapel (but we do not know where their Manor House or Hall was situated). Alternatively, like many other Wiltshire churches, it could have been sited close to the Roman Villa, a place of ancient significance, where it inherited the greatness of the ancient Romans and where stone could be plundered.[2] The early stone building was a simple rectangular shape, comprising a nave for laymen and a chancel for the priest, which possibly doubled as the vicar’s accommodation.[3] It was just such a building that William of Malmesbury described in 1125 as Churches rise in every village,[4] mass-produced buildings, thrown up quickly as were hundreds of others in the period before 1150.[5]

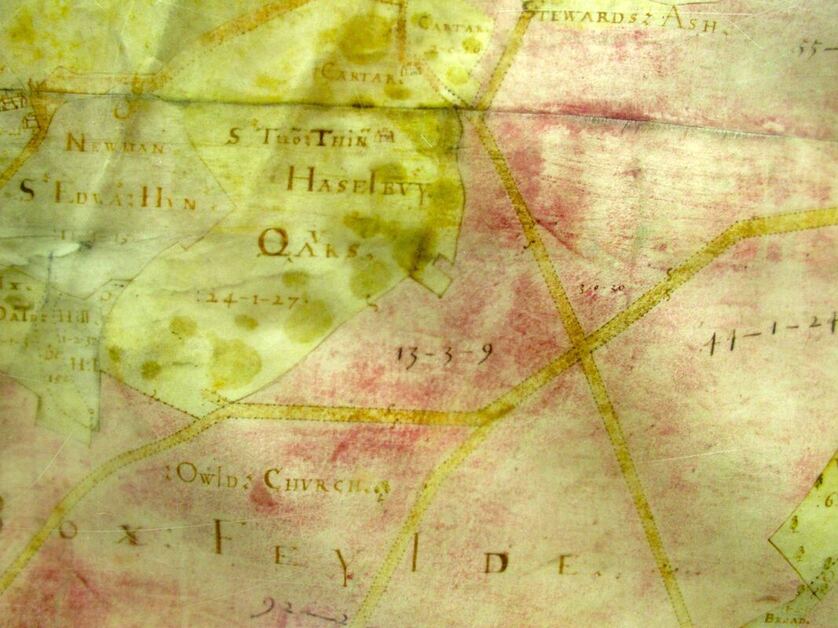

The Domesday survey records another church in the area at Hazelbury in 1086: Bishop Osbern has Hazelbury church with 1½ virgate of land, value 10s. It was held by Osbern bishop of Exeter who was also the rector of Chippenham Church.[6] This was a substantial amount of land (about 50 acres) held directly from the king. It is usually claimed that this church was that shown on Allen’s 1630 map as Oulde Church outside the central area at the intersection of field access tracks. In a later deed the church is cited as juxta Fogham (next to Fogham), suggesting it was nearer Foggam Barn.[7] Both locations suggest it was probably a preaching station in the centre of the common fields, as does the name All Saints which again reflects general usage.[8] In that event, it is likely that the ownership of adjacent field strips prevented a churchyard being established to hold the bones of the dead until the Second Coming.

Box Church quickly established local superiority as evidenced by a gift (undated but probably between 1190 and 1219) from Walter Croke of Hazelbury to St Peter’s Church at Box (ecclesie beati Petri Boxa). The gift comprised four acres in a field close to the chapel of St David at Hazelbury and it gives Box Church’s original name, St Peter.[9] Box had advantages that other local churches lacked burial rights and an income to support the priest. When Walter Croke gifted some of Hazelbury’s tithes to Bradenstoke Priory in about 1190, he called Hazelbury a chapel (capellam) meaning that it had no rights to bury parishioners, and he accepted that its subordination to Box as the mother church: all the tithes of my men of Haselbury and of Wadswick, save the half of the tithe of sheaves which belongs to the mother church (matricem ecclesiam).[10] A different situation existed at Ditteridge which had burial rights but too few parishioners to support a resident priest.[11] Box on the other hand had considerable small tithes, including calves, milk, cheese, lambs, wool, vegetables and fowl whose tithes went to support the priest.[12]

Norman Reformation

The Norman invasion of England had a spiritual element as well as political aims. The English Orthodox (or Western) Church had adopted different practices to the Franco-Papist centralisation based on one Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church led by Rome.

As a result, the Pope had banned the English archbishop Stigand in 1052 after his appointment by the lay king Edward the Confessor on the grounds of pluralism (holding two bishoprics).[13] Much of the subsequent Norman commitment to church reform in Box was the practical implementation of the Roman Papacy’s decrees.

Box Church complied with the important canon law reforms introduced after 1075 by Pope Gregory VII.[14] To regularise the parish system Gregory sought three things: that priests with care of souls (which covered most ecclesiae but not capellae) should have a defined area so that people knew which church received their tithes; that the church had an independent legal persona of which the vicar was the defender not the owner; and that there was sufficient income to the vicar to ensure continuity. Probably the arrangement suited all parties because the Bigods and Bohuns were prepared to fund the building; the Crokes wanted Hazelbury residents to have burial rights in the area; both lords were prepared to allow Malmesbury to retain their existing spiritual authority; and, perhaps above all, the Bohuns had the ear of the papacy to over-rule any other objections.

Walter Croke’s gift of land to Box Church between 1190 and 1219 names the church as St Peter’s Church and there is an absence of a patrimony in the gift of the church 1227 to Farleigh Priory. We might speculate that the Priory dedicated the name St Thomas à Becket between 1227 and 1291, when it was recorded as in the survey carried out by Pope Nicholas IV of church income in England, although it would be good to see the original survey document before confirming this.[15] More than 80 churches were re-dedicated to him after 1200.[16] A belief grew up of miraculous cures from St Thomas’ blood immediately after his murder by Henry II in 1170. We might imagine that Box acquired a sample of the waters of Canterbury (a phial of watered-down blood) which was put on show in Box Church for everyone to touch, venerate and leave donations.[17] It would have generated increased income for the church, as the patrimonal day for St Peter was 29 June, not a good date for donations before the yearly harvest was gathered. The local feast day changed to 29 December at the full abundance of the autumn surplus harvest and Hazelbury chapel was possibly a Thomas chapel for daily prayers to be said by the chantry priest.[18]

Cluniac Order at Farleigh Priory

The Priory was a Cluniac house, a strict Benedictine order, founded by Humphrey de Bohun II in 1120. Farleigh Priory was the fourth daughter church established by Lewes Priory, Sussex (founded 1077) and grouped under the Abbey of Cluny in Burgundy. The deed by Humphrey III confirming its establishment was witnessed by Bartholomew Bigot.[19] The Priory had specific aims in its foundation, hiring labour to manage the estate which allowed monks to concentrate on prayer. Silence, cleanliness, and order put the Cluniacs at the forefront of religious observance and becoming one of the wealthiest orders in Europe.[20] There was a slew of local land and ecclesiastic donations to the Priory in the years that followed its foundation including Chippenham, Slaughterford, Broughton Gifford and Trowbridge. Farleigh was highly regarded and in 1184 Pope Lucas gave it protection by the Holy See.

But the order was in decline by the 1200s.[21] After 1217 there was pressure from an entirely new movement, the missionary friars, monks who lived and worked amongst the poorest in society, the opposite of the closed monasteries. They caught the mood of a time excited by the Renaissance and the rediscovery of Aristotle. Various friar orders came to England, including Dominicans (Black Friars) in 1217, Franciscans (Grey Friars) in 1224, Carmelites (White Friars) and Austen Friars. These were preaching orders and, because they were mendicant (surviving by charitable donations), they attracted considerable bequests, to the detriment of the monasteries. At approximately the date of its construction, Humphrey de Bohun gifted Box Church to Farleigh Priory in 1227 saying that it was in recognition of the poverty of the Priory and its hospitality to all comers, at the request of Richard Poore Bishop of Salisbury, The Bohuns had family connections with the priory which had been founded by Humphrey’s great grandfather.[22] The gift had local implications and introduced a higher standard of priest, ending any landlord nepotism of semi-literate laymen, with only rudimentary knowledge of the scriptures.[23] The transfer meant that Farleigh Priory retained the great tithes, licences and rental income and the priest at Box Church was stipendiary.[24]

Box Church had to work hard for its income. As the superior church, Box had the tithe income from Hazelbury but it held little local land and was not on a pilgrim's trail. In 1291 the value of Box Church was recorded as: Great tithes due to the Priory £13.6s.8d; Lesser tithes due to the vicar £4.6s.8d.[25] The Priory monks guarded its assets in Box carefully. Balaam's Passage was reputed to be the pathway to the Priory (mirroring Balaam’s journey on a donkey to praise the Israelites) which reflects how the Priory’s involvement in Box Church was a positive happening. In 1249 there was a dispute over the tenancy of a mill: Assize of mort d’ancestor to declare whether Walter Crok’ uncle of Henry Crok’ was seised of 1/2 virgate of land and 1 mill at Hasilbergh, which the prior of Farnlegh holds.[26] Land transactions in the second half of the 13th century show how the commercial acumen of the Farleigh monks with many gifts to the Priory to secure them a substantial income.[27]

The story of the Priory in the 14th century was one of continual interference by the king, taking possession of all alien priories and releasing them against payment of fines. This undermined the authority of the Farleigh Prior and its autonomy and probably influenced his authority in Box. At its maximum, the house seems to have had about 20 monks but by its dissolution in 1535 was down to 8. Presumably by then its influence in Box was minimal.

Box Church quickly established local superiority as evidenced by a gift (undated but probably between 1190 and 1219) from Walter Croke of Hazelbury to St Peter’s Church at Box (ecclesie beati Petri Boxa). The gift comprised four acres in a field close to the chapel of St David at Hazelbury and it gives Box Church’s original name, St Peter.[9] Box had advantages that other local churches lacked burial rights and an income to support the priest. When Walter Croke gifted some of Hazelbury’s tithes to Bradenstoke Priory in about 1190, he called Hazelbury a chapel (capellam) meaning that it had no rights to bury parishioners, and he accepted that its subordination to Box as the mother church: all the tithes of my men of Haselbury and of Wadswick, save the half of the tithe of sheaves which belongs to the mother church (matricem ecclesiam).[10] A different situation existed at Ditteridge which had burial rights but too few parishioners to support a resident priest.[11] Box on the other hand had considerable small tithes, including calves, milk, cheese, lambs, wool, vegetables and fowl whose tithes went to support the priest.[12]

Norman Reformation

The Norman invasion of England had a spiritual element as well as political aims. The English Orthodox (or Western) Church had adopted different practices to the Franco-Papist centralisation based on one Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church led by Rome.

As a result, the Pope had banned the English archbishop Stigand in 1052 after his appointment by the lay king Edward the Confessor on the grounds of pluralism (holding two bishoprics).[13] Much of the subsequent Norman commitment to church reform in Box was the practical implementation of the Roman Papacy’s decrees.

Box Church complied with the important canon law reforms introduced after 1075 by Pope Gregory VII.[14] To regularise the parish system Gregory sought three things: that priests with care of souls (which covered most ecclesiae but not capellae) should have a defined area so that people knew which church received their tithes; that the church had an independent legal persona of which the vicar was the defender not the owner; and that there was sufficient income to the vicar to ensure continuity. Probably the arrangement suited all parties because the Bigods and Bohuns were prepared to fund the building; the Crokes wanted Hazelbury residents to have burial rights in the area; both lords were prepared to allow Malmesbury to retain their existing spiritual authority; and, perhaps above all, the Bohuns had the ear of the papacy to over-rule any other objections.

Walter Croke’s gift of land to Box Church between 1190 and 1219 names the church as St Peter’s Church and there is an absence of a patrimony in the gift of the church 1227 to Farleigh Priory. We might speculate that the Priory dedicated the name St Thomas à Becket between 1227 and 1291, when it was recorded as in the survey carried out by Pope Nicholas IV of church income in England, although it would be good to see the original survey document before confirming this.[15] More than 80 churches were re-dedicated to him after 1200.[16] A belief grew up of miraculous cures from St Thomas’ blood immediately after his murder by Henry II in 1170. We might imagine that Box acquired a sample of the waters of Canterbury (a phial of watered-down blood) which was put on show in Box Church for everyone to touch, venerate and leave donations.[17] It would have generated increased income for the church, as the patrimonal day for St Peter was 29 June, not a good date for donations before the yearly harvest was gathered. The local feast day changed to 29 December at the full abundance of the autumn surplus harvest and Hazelbury chapel was possibly a Thomas chapel for daily prayers to be said by the chantry priest.[18]

Cluniac Order at Farleigh Priory

The Priory was a Cluniac house, a strict Benedictine order, founded by Humphrey de Bohun II in 1120. Farleigh Priory was the fourth daughter church established by Lewes Priory, Sussex (founded 1077) and grouped under the Abbey of Cluny in Burgundy. The deed by Humphrey III confirming its establishment was witnessed by Bartholomew Bigot.[19] The Priory had specific aims in its foundation, hiring labour to manage the estate which allowed monks to concentrate on prayer. Silence, cleanliness, and order put the Cluniacs at the forefront of religious observance and becoming one of the wealthiest orders in Europe.[20] There was a slew of local land and ecclesiastic donations to the Priory in the years that followed its foundation including Chippenham, Slaughterford, Broughton Gifford and Trowbridge. Farleigh was highly regarded and in 1184 Pope Lucas gave it protection by the Holy See.

But the order was in decline by the 1200s.[21] After 1217 there was pressure from an entirely new movement, the missionary friars, monks who lived and worked amongst the poorest in society, the opposite of the closed monasteries. They caught the mood of a time excited by the Renaissance and the rediscovery of Aristotle. Various friar orders came to England, including Dominicans (Black Friars) in 1217, Franciscans (Grey Friars) in 1224, Carmelites (White Friars) and Austen Friars. These were preaching orders and, because they were mendicant (surviving by charitable donations), they attracted considerable bequests, to the detriment of the monasteries. At approximately the date of its construction, Humphrey de Bohun gifted Box Church to Farleigh Priory in 1227 saying that it was in recognition of the poverty of the Priory and its hospitality to all comers, at the request of Richard Poore Bishop of Salisbury, The Bohuns had family connections with the priory which had been founded by Humphrey’s great grandfather.[22] The gift had local implications and introduced a higher standard of priest, ending any landlord nepotism of semi-literate laymen, with only rudimentary knowledge of the scriptures.[23] The transfer meant that Farleigh Priory retained the great tithes, licences and rental income and the priest at Box Church was stipendiary.[24]

Box Church had to work hard for its income. As the superior church, Box had the tithe income from Hazelbury but it held little local land and was not on a pilgrim's trail. In 1291 the value of Box Church was recorded as: Great tithes due to the Priory £13.6s.8d; Lesser tithes due to the vicar £4.6s.8d.[25] The Priory monks guarded its assets in Box carefully. Balaam's Passage was reputed to be the pathway to the Priory (mirroring Balaam’s journey on a donkey to praise the Israelites) which reflects how the Priory’s involvement in Box Church was a positive happening. In 1249 there was a dispute over the tenancy of a mill: Assize of mort d’ancestor to declare whether Walter Crok’ uncle of Henry Crok’ was seised of 1/2 virgate of land and 1 mill at Hasilbergh, which the prior of Farnlegh holds.[26] Land transactions in the second half of the 13th century show how the commercial acumen of the Farleigh monks with many gifts to the Priory to secure them a substantial income.[27]

The story of the Priory in the 14th century was one of continual interference by the king, taking possession of all alien priories and releasing them against payment of fines. This undermined the authority of the Farleigh Prior and its autonomy and probably influenced his authority in Box. At its maximum, the house seems to have had about 20 monks but by its dissolution in 1535 was down to 8. Presumably by then its influence in Box was minimal.

References

[1] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collection, re-published 1862, The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.55

[2] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, 1990, p.250 and Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, Settlement and Society: Wiltshire in the First Millennium AD, 2004, Durham University Thesis, p.133-35

[3] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, St Thomas à Becket Church Guide and Brief History, p.11

[4]Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.24

[5] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.239

[6] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol III, p.26

[7] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.79

[8] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol X, p.284

[9] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.49 and 253

[10] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.49 and 253

[11] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.233

[12] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.227

[13] Vladimir Moss, The Fall of Orthodox England, 2011, p.4

[14] Aston & Lewis, The Medieval Landscape of Wessex, p.70

[15] The Taxatio Ecclesiastica Database for Benefice SA.WI.MM.04

[16] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.157

[17] History Extra podcast 24 May 2012

[18] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.49 and 253 and Martin and Elizabeth Devon, St Thomas à Becket Church Guide and Brief History, p.5

[19] House of Cluniac monks: Priory of Monkton Farleigh | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk)

[20] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XX, p.218

[21] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.24

[22] Victoria County History, Vol IV

[23] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.164

[24] John vicario de Boxe is referred to in Sampson Bigod II’s accession charter

[25] The Taxatio Ecclesiastica Database for Benefice SA.WI.MM.04

[26] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 26, p.85

[27] House of Cluniac monks: Priory of Monkton Farleigh | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk)

[1] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collection, re-published 1862, The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.55

[2] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, 1990, p.250 and Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, Settlement and Society: Wiltshire in the First Millennium AD, 2004, Durham University Thesis, p.133-35

[3] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, St Thomas à Becket Church Guide and Brief History, p.11

[4]Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.24

[5] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.239

[6] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol III, p.26

[7] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.79

[8] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol X, p.284

[9] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.49 and 253

[10] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.49 and 253

[11] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.233

[12] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.227

[13] Vladimir Moss, The Fall of Orthodox England, 2011, p.4

[14] Aston & Lewis, The Medieval Landscape of Wessex, p.70

[15] The Taxatio Ecclesiastica Database for Benefice SA.WI.MM.04

[16] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.157

[17] History Extra podcast 24 May 2012

[18] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.49 and 253 and Martin and Elizabeth Devon, St Thomas à Becket Church Guide and Brief History, p.5

[19] House of Cluniac monks: Priory of Monkton Farleigh | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk)

[20] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XX, p.218

[21] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.24

[22] Victoria County History, Vol IV

[23] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, p.164

[24] John vicario de Boxe is referred to in Sampson Bigod II’s accession charter

[25] The Taxatio Ecclesiastica Database for Benefice SA.WI.MM.04

[26] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 26, p.85

[27] House of Cluniac monks: Priory of Monkton Farleigh | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk)