Box in Domesday Book Alan Payne October 2023

The record of local lands in the Domesday Book has been extensively researched and recorded, so this is only a brief outline.[1] gives a fascinating but challenging picture of Box in 1086. Part of the problem is that William I died a year later and his empire was split between Robert Curthose who took Normandy and the younger son, William Rufus, who took England. In the ensuing civil war, allegiances divided and lordships abruptly changed.

The Hazelbury Holdings

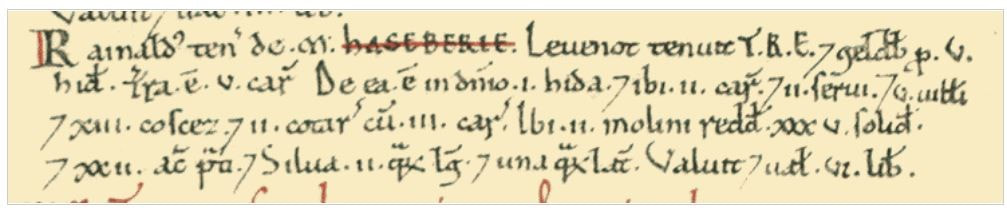

The largest local land holding in the area in 1086 was described as:

The largest local land holding in the area in 1086 was described as:

Rainald holds HAZELBURY from Milo (Miles). Leofnoth held it before 1066; it paid tax for 5 hides. Land for 5 ploughs, of which 1 hide is in lordship; 2 ploughs there; 2 slaves; 5 villani, 13 Cottars and 2 cottars with 3 ploughs. 2 mills which pay 35s; meadow, 22 acres; woodland 2 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. The value was and is £6.[2]

The area described in Domesday cannot be exactly our modern concept of Hazelbury. Rather, it appears to include much of the area we now call Box because the mills would have been on the By Brook.[3] The land appears to include the Box common fields down to the By Brook; in other words, most of the farming land in the village. We can speculate about which fields are described. The land for 5 ploughs may have been the open-field area used in common by the villani (villeins or tenant farmers) of which they cultivated one hide for the lord.[4] The 22 acres of meadow may still be reflected in the name The Ley (meaning temporary pasture). The woodland could have been the ancient wood areas running up the hillside either side of Box Bottom towards modern Box Fiveways.[5]

We can also add something about the inhabitants of the area at that time. We might imagine that the 22 inhabitants listed represented about 100 – or so - residents. The miller would have lived close to the two mills (traditionally believed to be Box and Drewetts Mills) and it is likely that other residents took advantage of the frequency of passing trade so set up work as wheelwrights, blacksmiths and similar in the same locations. The villeins were tenant farmers presumably occupying larger areas of land (probably some in the hamlets at this time as documented by witnesses to the grant of a mill in 1131). The traditional view of cottars is that they grouped together in crofts surrounded by small landholdings for their domestic husbandry needs. From there they walked daily to their strips in the surrounding open-fields. There are several contemporary references to Box’s crofts: a certain croft which Midewynter held (before 1207), the croft which is called Lepeyate, which lies next to that land of theirs called Smith’s croft.[6]

The record states that the lord held a home farm in the area supplying his own personal needs and presumably the slaves were agricultural workers engaged in either the lord’s residence or on his farm. There are some views that they may have been ploughmen who worked as a crew of two on the lord’s ploughing work.[7]

Leofnoth, Box’s pre-Conquest thegn (lord), was possibly killed at the Battle of Hastings and he was replaced by Miles Crispin and his sub-tenant, Rainald. The Crispins were one of the great medieval dynasties. The father, William Crispin, and his sons fought alongside William the Conqueror at Hastings. It is doubtful that Miles ever visited Box. He held the Honour of Wallingford in Berkshire as well as 88 other lordships in England, dying in 1107.[8] The Hazelbury estate continued to pay an annual rent of

2 shillings to Wallingford until 1652.[9] Miles’ tenant, Rainald, is believed to be Reginald Cnut (or Croc). He held 7 manors in Wiltshire together with 20 manors in Oxfordshire and 3 in Southampton.[10] These families were Norman, who spoke French (rather than the coarse English) and whose home and power base was overseas. For example, King Richard I only spent six months of his 10-year reign in England. After Rainald’s death the estate passed to the Crokes of Cannock Chase, Staffordshire until one branch settled in Hazelbury.

It was a time of sudden power shifts in a highly military society. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes William in 1087 as:

The king and his head men loved much, and over-much, the greed for gold and silver ... The king granted his land on hard terms … when some other came and bid more than the first had given, the king let it to the man who offered more… no man dared against his will. He had earls in chains, who went against his will; bishops he deposed from their bishoprics, and thanes he set in prison. It was worse after the death of the Conqueror when Normandy went to the eldest son, Robert Curthose, and the English crown went to Robert’s younger brother William Rufus. This schism necessitated a choice of fealty by the nobility who held land in both countries. The Chronicle describes local insurrection: Bishop Gosfrith and Robert a Mowbray fared to Bristol, ravaged it and brought the plunder to the castle, and after left the castle and ravaged Bath and all the land thereabout and to Berkeley Harness they laid waste.

We can also add something about the inhabitants of the area at that time. We might imagine that the 22 inhabitants listed represented about 100 – or so - residents. The miller would have lived close to the two mills (traditionally believed to be Box and Drewetts Mills) and it is likely that other residents took advantage of the frequency of passing trade so set up work as wheelwrights, blacksmiths and similar in the same locations. The villeins were tenant farmers presumably occupying larger areas of land (probably some in the hamlets at this time as documented by witnesses to the grant of a mill in 1131). The traditional view of cottars is that they grouped together in crofts surrounded by small landholdings for their domestic husbandry needs. From there they walked daily to their strips in the surrounding open-fields. There are several contemporary references to Box’s crofts: a certain croft which Midewynter held (before 1207), the croft which is called Lepeyate, which lies next to that land of theirs called Smith’s croft.[6]

The record states that the lord held a home farm in the area supplying his own personal needs and presumably the slaves were agricultural workers engaged in either the lord’s residence or on his farm. There are some views that they may have been ploughmen who worked as a crew of two on the lord’s ploughing work.[7]

Leofnoth, Box’s pre-Conquest thegn (lord), was possibly killed at the Battle of Hastings and he was replaced by Miles Crispin and his sub-tenant, Rainald. The Crispins were one of the great medieval dynasties. The father, William Crispin, and his sons fought alongside William the Conqueror at Hastings. It is doubtful that Miles ever visited Box. He held the Honour of Wallingford in Berkshire as well as 88 other lordships in England, dying in 1107.[8] The Hazelbury estate continued to pay an annual rent of

2 shillings to Wallingford until 1652.[9] Miles’ tenant, Rainald, is believed to be Reginald Cnut (or Croc). He held 7 manors in Wiltshire together with 20 manors in Oxfordshire and 3 in Southampton.[10] These families were Norman, who spoke French (rather than the coarse English) and whose home and power base was overseas. For example, King Richard I only spent six months of his 10-year reign in England. After Rainald’s death the estate passed to the Crokes of Cannock Chase, Staffordshire until one branch settled in Hazelbury.

It was a time of sudden power shifts in a highly military society. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes William in 1087 as:

The king and his head men loved much, and over-much, the greed for gold and silver ... The king granted his land on hard terms … when some other came and bid more than the first had given, the king let it to the man who offered more… no man dared against his will. He had earls in chains, who went against his will; bishops he deposed from their bishoprics, and thanes he set in prison. It was worse after the death of the Conqueror when Normandy went to the eldest son, Robert Curthose, and the English crown went to Robert’s younger brother William Rufus. This schism necessitated a choice of fealty by the nobility who held land in both countries. The Chronicle describes local insurrection: Bishop Gosfrith and Robert a Mowbray fared to Bristol, ravaged it and brought the plunder to the castle, and after left the castle and ravaged Bath and all the land thereabout and to Berkeley Harness they laid waste.

Other Hazelbury Holdings

There were three smaller areas listed under Hazelbury, probably reflecting previous grants and sales of land before the Conquest.

Nigel the doctor had a small holding in Hazelbury: Before 1066 (Alsi the priest held it) it paid tax for 1 virgate of land (quarter of a hide). Land for 6 oxen. 3 smallholders. Meadow, 3 acres; pasture 4 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. Value 10s.

Nigel the doctor held the land directly of the king and it appears to be a gift for services provided. Nigel acquired 35 landholdings after the Conquest, including many in Wiltshire, Somerset, Gloucestershire, and Hampshire. His most valuable holding was Avenbury, Herefordshire, which was worth £5 in 1086 and included 2 priests. Many of his holdings were small; basically, the land held by Spirtes the priest before the Conquest.[11] Several of his lands were gifted to French monasteries and Nigel appears to have sided with William’s half-brother, Robert, Count of Mortain, who supported Robert Curthose after William’s death. It is probable that this holding changed hands shortly after 1087.

Cypping had a holding: Before 1066; it paid tax for 1 virgate of land. Land for 1 plough, which is there.

Woodland 2 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. Value 7s.

Woodland 2 furlongs long and 1 furlong wide. Value 7s.

Cypping (of Worthy, possibly near Winchester) held this land both before and after 1066. It was one of 35 holdings he retained, almost all in Hampshire and in total worth about £48. It is suggested that this holding was the modern Henley.[12]

Bishop Osbern held Hazelbury church with 1/2 virgate of land. Value 10s.

Osbern was the Bishop of Exeter, who had previously served as clerk to King Edward the Confessor before 1066. The Exeter bishopric held 48 separate churches and lands in 1086, including extensive properties in Chippenham. This holding has traditionally been assumed to be the Oulde Church on the Allen 1626 map.

Ditteridge

Ditteridge had a single owner. Under the holding of tenant-in-chief William of Eu was Warner of Ditteridge, described as:

Osbern was the Bishop of Exeter, who had previously served as clerk to King Edward the Confessor before 1066. The Exeter bishopric held 48 separate churches and lands in 1086, including extensive properties in Chippenham. This holding has traditionally been assumed to be the Oulde Church on the Allen 1626 map.

Ditteridge

Ditteridge had a single owner. Under the holding of tenant-in-chief William of Eu was Warner of Ditteridge, described as:

Before 1066 (Aelstan held Ditteridge) it paid tax for 1 hide and 3 virgates of land. Land for 1 plough, which is there, in lordship; 2 villani and 4 cottars. Half mill which pays 5s; meadow, 7 acres; pasture, 15 acres; underwood, 17 acres. Value 30s. An Abbot of Malmesbury leased 1 hide of this land to Aelstan (before 1066)

To understand what happened to the lord of Ditteridge after 1086, we need to explore the story of a different person, Odo Bishop of Bayeux, who was William the Conqueror’s half-brother. Odo fought with William at Hastings in 1066 but they fell out in 1082. Odo was captured attempting to flee England and his English lands were forfeited to the King. He was banished to Normandy where he retained his possessions and played an active role in the duchy. On King William’s death, Odo was a leader in a rebellious plot in 1088 to support Robert Curthose.

The rebellion by Odo included William of Eu (who held Ditteridge) and Roger Bigod.[13] The rebels burnt Bath and Berkley but were captured. Odo was never allowed to return to England and he focussed his attention on supporting the First Crusade, dying on route in Sicily in 1097. Worse befell William of Eu who was implicated in a further rebellion in 1095, lost a trial by combat and was blinded, castrated, and died shortly thereafter of his wounds, called by the chronicler Oderic prince of traitors.[14]

The ownership moved to the king and custodianship of the Marshall family. Warner of Ditteridge also held land in Somerset at Chilton Cantelo,

The rebellion by Odo included William of Eu (who held Ditteridge) and Roger Bigod.[13] The rebels burnt Bath and Berkley but were captured. Odo was never allowed to return to England and he focussed his attention on supporting the First Crusade, dying on route in Sicily in 1097. Worse befell William of Eu who was implicated in a further rebellion in 1095, lost a trial by combat and was blinded, castrated, and died shortly thereafter of his wounds, called by the chronicler Oderic prince of traitors.[14]

The ownership moved to the king and custodianship of the Marshall family. Warner of Ditteridge also held land in Somerset at Chilton Cantelo,

The Domesday Record gives the names of the owners of the area but subsequent disruption meant that they were dispossessed shortly after. Local historians have often concentrated on whether there was an area called Box at this time and what happened to the village of Hazelbury. This may have been a red herring as probably the Domesday Book gives us a better record of the topography of the area and the unnamed tenants who worked there,

References

[1] See GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, Methuen, and Jane Cox, The Norman Conquest of Box Wiltshire, 2016, Ex-Libris Press

[2] Ploughs = the farm implement made of wood and iron and the teams of 8 oxen needed to pull them. Hides = the amount of land that the team could plough in a year

[3] The first windmills came to England a century later, probably introduced by returning Crusaders

[4] WG Hoskins, Local History in England, 1972, Longman, p.45

[5] Based on 1 acre = 1-furlong long x 1/10 furlong wide; 1 hide =120 acres; 1 virgate = 1/4 hide; 1 ox land = 1/2 virgate

[6] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.101

[7] Christopher Dyer, Making a Living in the Middle Ages, 2002, Yale University Press, p.92

[8] JR Planche, 1874, The Conqueror and His Companions

[9] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.9

[10] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.31

[11] Introduction to the Somerset Domesday | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk)

[12] Jane Cox, The Norman Conquest of Box Wiltshire, 2016, Ex-Libris Press, p.61-62

[13] Catherine Lack, Conqueror’s Son, 2007, Sutton Publishing, p.42

[14] Catherine Lack, Conqueror’s Son, 2007, Sutton Publishing, p.70-71References

[1] See GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, Methuen, and Jane Cox, The Norman Conquest of Box Wiltshire, 2016, Ex-Libris Press

[2] Ploughs = the farm implement made of wood and iron and the teams of 8 oxen needed to pull them. Hides = the amount of land that the team could plough in a year

[3] The first windmills came to England a century later, probably introduced by returning Crusaders

[4] WG Hoskins, Local History in England, 1972, Longman, p.45

[5] Based on 1 acre = 1-furlong long x 1/10 furlong wide; 1 hide =120 acres; 1 virgate = 1/4 hide; 1 ox land = 1/2 virgate

[6] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.101

[7] Christopher Dyer, Making a Living in the Middle Ages, 2002, Yale University Press, p.92

[8] JR Planche, 1874, The Conqueror and His Companions

[9] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.9

[10] GJ Kidston, A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.31

[11] Introduction to the Somerset Domesday | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk)

[12] Jane Cox, The Norman Conquest of Box Wiltshire, 2016, Ex-Libris Press, p.61-62

[13] Catherine Lack, Conqueror’s Son, 2007, Sutton Publishing, p.42

[14] Catherine Lack, Conqueror’s Son, 2007, Sutton Publishing, p.70-71References