Tudor and Stuart Manor Houses in Box Alan Payne January 2016

The earliest private residential houses tend to date from the Tudor period for the interiors and the Stuart period for the building itself. This is not because there was a general property rebuilding custom at that time (as was once thought) but rather because the materials used prevented water ingress because private owners could afford stone walls, stone roof tiles and glass windows.

The words Manor House imply more than just a grand building. It was an authority for the regulation of the lives of the people in the surrounding area. In the late medieval period there was a manorial court controlling agricultural crops and law and order. But by Tudor times this was turning into a more general deference characterised by the description of the lord as Esquire or a Gentleman. These are the manor houses that we know of in Box.

The words Manor House imply more than just a grand building. It was an authority for the regulation of the lives of the people in the surrounding area. In the late medieval period there was a manorial court controlling agricultural crops and law and order. But by Tudor times this was turning into a more general deference characterised by the description of the lord as Esquire or a Gentleman. These are the manor houses that we know of in Box.

|

1. Box Manor House

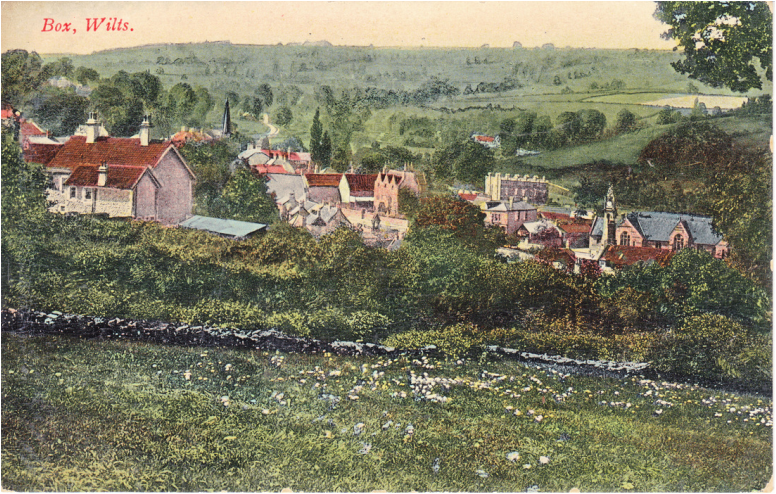

The Manor House is, of course, right in the centre of Box village. The house was rebuilt in about 1609 by Hugh Speke as a show house, the manifestation of his takeover of the manor of Box.[1] We don't know what the earlier house looked like before Speke rebuilt it but we might imagine it was an old-fashioned feudal hall with just two rooms: a long Great Hall for people, servants and animals, with a solar (private chamber) above it for the family 's bedchamber.[2] It was a three-storey house built of stone that lasts longer than wood and showed the owner's wealth. But Hugh did not take up residence; he let it out to his leading farming tenant. |

The house was built of ashlar (cut stone) blocks in order to impress, with a stone tiled roof and gable ends (overhanging stones on straight end walls). There are several Tudor-style features: the main entrance doorway, a stone fireplace and fine oak spiral staircase. The new house had a parlour (family dining room), fireplaces on side walls rather than an open central fire, and glass at windows instead of shutters or parchment coverings.[3]

Manor Barn

The property was on the brow of the ridge, standing alone in open fields, approached by the lane from The Market Place.[4] The site was designed as an early farmstead with a splendid stone barn to the west, positioned to allow the prevailing west/east wind to pass across the threshing bay for winnowing the corn. The central threshing floor has four storage bays surrounded by aisles for easy cart access. An external porch extends the threshing floor for extra weather protection.[5]

The barn was for storage and for processing corn, entirely different to the medieval threshing arrangements typified by great outlying tithe barns in the middle of open fields.[6] It was convenient for the tenant to supervise work but it wasn't designed as a four-sided farmstead unit for livestock, which played such a part in later farm plans.

The property was on the brow of the ridge, standing alone in open fields, approached by the lane from The Market Place.[4] The site was designed as an early farmstead with a splendid stone barn to the west, positioned to allow the prevailing west/east wind to pass across the threshing bay for winnowing the corn. The central threshing floor has four storage bays surrounded by aisles for easy cart access. An external porch extends the threshing floor for extra weather protection.[5]

The barn was for storage and for processing corn, entirely different to the medieval threshing arrangements typified by great outlying tithe barns in the middle of open fields.[6] It was convenient for the tenant to supervise work but it wasn't designed as a four-sided farmstead unit for livestock, which played such a part in later farm plans.

The Pound

The Pound is a reminder of this, an enclosure for keeping stray animals, controlled by the lord of the manor, and sited adjacent to the barn of the Manor House. It was mainly useful before fenced enclosure restricted the open migration of animals. Since early feudal times the manorial court appointed a pound-keeper, responsible for feeding and watering the animals, to whom a fine had to be paid before their release and a charge can still be made of £20 for this.[7]

The Pound is a reminder of this, an enclosure for keeping stray animals, controlled by the lord of the manor, and sited adjacent to the barn of the Manor House. It was mainly useful before fenced enclosure restricted the open migration of animals. Since early feudal times the manorial court appointed a pound-keeper, responsible for feeding and watering the animals, to whom a fine had to be paid before their release and a charge can still be made of £20 for this.[7]

Box Manor has intrigued residents for many years including a rumour that it had a secret passageway connecting it with Hazelbury Manor, two miles away.

2. Hazelbury Manor

|

When the travel writer John Leland visited Hazelbury about 1536 he described it as: The Manor Place of Haselbyry stondith in a litle Vale, and was a Thing of simple Building afore that old Mr Boneham Father did build there.[8]

The Bonham family were typical of the rising gentry class in the Tudor period. They came from humble yeomen beginnings and rose through hard work and judicious marriage, including John Bonham's wedding to Ann Croke, heiress of John Croke of Hazelbury. The marriage in 1475 is documented in English reflecting the local rural accent: Thys indentur ... wytnessythe ... to the seyd John Bonham and to Ann hys wyffe the dowzter (daughter) of the seyd John Croke.[9] Anne’s marriage settlement included the Manor of Hazelbury and 1 dovecote, 1 garden, 140 acres of land, 6 acres meadow, 40 acres pasture and 120 acres wood there.[10] |

The third John Bonham bought the dissolved abbey at Lacock in 1540 and in 1544 Farleigh Priory’s possessions in Box from Sir William Sharington. This included the rectory and advowson (right to nominate the vicar) of Box Church, various lands and tenements, 1½ virgates in Wadswick called Raylands, a tithe barn and the Great Tithes (corn and hay) in Rudloe.[11]

The Bonham's monument in the area is the manor house at Hazelbury, which they rebuilt. They borrowed and invested heavily to take advantage of inflation. John Bonham III became Sheriff of Wiltshire, bought a knighthood, and married Lady Anne Mountjoy. Shortly thereafter they left Hazelbury, which was rented out, moving to Westbury.[12]

The Bonham's monument in the area is the manor house at Hazelbury, which they rebuilt. They borrowed and invested heavily to take advantage of inflation. John Bonham III became Sheriff of Wiltshire, bought a knighthood, and married Lady Anne Mountjoy. Shortly thereafter they left Hazelbury, which was rented out, moving to Westbury.[12]

|

But the family fortune started to decline with a series of disputes and court cases and much of their land was subject to mortgage or sale after 1573.[13]

Royal Visit, 1575 There was still one pretension to grandeur, however, welcoming Queen Elizabeth I to the area on 23 August 1575. Her secretary recorded events as: Her Majestie removed from Bathe to Mr Bonhams at Hazelburie to dinner and afterwards to Mr Sheringtons.[14] The Elizabethan royal progresses were great state occasions. The queen often travelled in a litter, accompanied by the great officers of state, hundreds of lesser ranks with 600 baggage wagons pulled by thousands of horses.[15] |

This was the last throw of the dice for the Bonhams. The family had significantly over-reached themselves and disaster came quickly. Matthew Smyth (agent for Sir John Smyth of Long Ashton) took possession of the advowsons of Box and Hazelbury Churches in 1578 when the family defaulted on their 1574 mortgage.[16] Sir John Young of Bristol acquired whatever was left of the estate in 1580. It was not to be long lasting, however, because the Youngs held the property for less than 30 years, before selling to the Spekes in 1602.

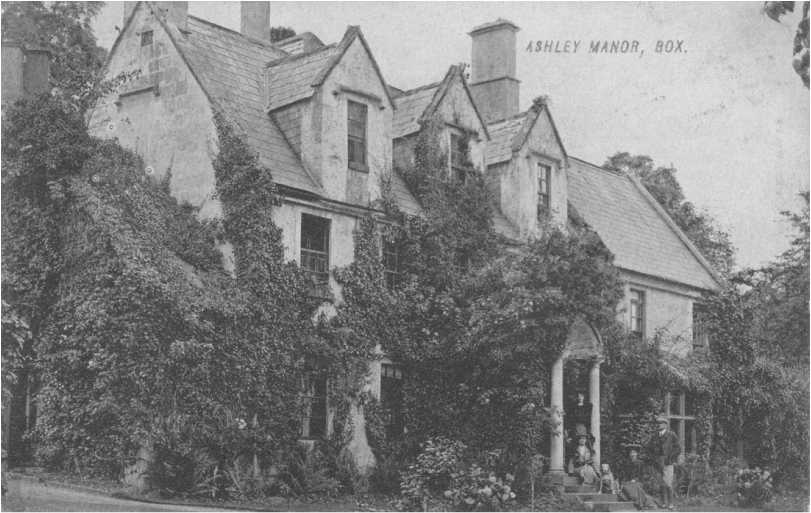

3. Ashley Manor

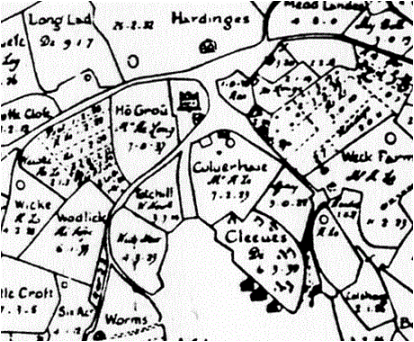

The Long family rebuilt Ashley Manor after about 1550 when a very junior branch of the family settled there following the marriage of Anthony Long, the fourth of seven sons of Sir Henry Long, to a local woman, Alice Butler.[17] The building is shown as a very significant property in Allen’s 1630 map.

The Long family became of great local influence as can still be seen from the array of insignia and epitaphs in Box church. Anthony’s effigy carries the inscription: Here lyeth the body of Anthony Long, Esqr, buried 2nd of May 1578. Originally the Longs were clothiers and John Aubrey describes them: The Longs are now the most flourishing and numerous family in the county.

The Long family rebuilt Ashley Manor after about 1550 when a very junior branch of the family settled there following the marriage of Anthony Long, the fourth of seven sons of Sir Henry Long, to a local woman, Alice Butler.[17] The building is shown as a very significant property in Allen’s 1630 map.

The Long family became of great local influence as can still be seen from the array of insignia and epitaphs in Box church. Anthony’s effigy carries the inscription: Here lyeth the body of Anthony Long, Esqr, buried 2nd of May 1578. Originally the Longs were clothiers and John Aubrey describes them: The Longs are now the most flourishing and numerous family in the county.

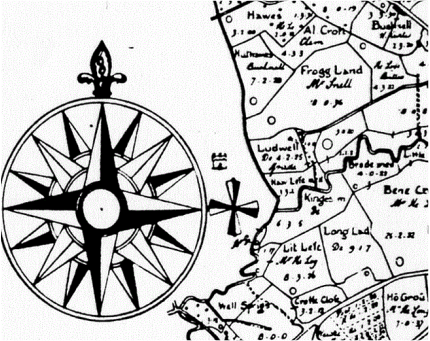

Francis Allen's map (courtesy Wiltshire History Centre); Left: the original map of 1626 and Right: the 1630 map from the 1907 transcription

The Long family took advantage of a rapidly changing situation in Tudor Box.[18] We believe that they grabbed land field by field in the area and exploited this through the enclosure of common pasture land. We can see this at Ashley where small parcels of enclosed dairy land replaced the arable field strips to the east and west of the manor house.

It was a boom time for those who borrowed long and invested in property and income-raising assets and the Long family become wealthy in the Box area by property speculation.

It was a boom time for those who borrowed long and invested in property and income-raising assets and the Long family become wealthy in the Box area by property speculation.

4. Cheney Court

The Bath Chronicle of 1910 recorded about the house that It was at this house that Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I, held her Court. A peculiarity of the entrance hall is that on the left is a raised dais, which it is supposed was erected for the Queen, the lower part of the Hall being used by the Royal retinue.[19]

The Bath Chronicle of 1910 recorded about the house that It was at this house that Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I, held her Court. A peculiarity of the entrance hall is that on the left is a raised dais, which it is supposed was erected for the Queen, the lower part of the Hall being used by the Royal retinue.[19]

|

King Charles I had married Henrietta Maria, daughter of Henry IV of France, in 1625. The marriage was deeply unpopular in the country at large because she was a Catholic and insisted on having mass held in the royal court.

The newspaper was repeating the Royalist connection that has traditionally been associated with the Court. Contemporary John Aubrey claimed this when he said: There is a tradition that (Cheney) Court, which is large and surrounded by a high wall, was used for some military purpose in the Civil Wars.[20] By popular legend, during her escape to France in July 1644, Queen Henrietta Maria, Catholic wife of Charles I, hid in the barn of Cheney Court to avoid Cromwell's troops.[21] The visit was reported by Sir William Dugdale who wrote in his diary on 17 April The Queen went out of Oxford towards Exeter. The King went with her to Abingdon where she lay the night and returned to Oxford the next day. It had been decided that it was not safe for her to continue at Oxford, especially as the King was about to take the field and she would be alone with a large body of Parliamentary troops as near as Marlborough. So when she left Oxford, the King accompanied her to Abingdon where he took leave of her for ever. |

This is perhaps rather speculative but we are unlikely to have better confirmation than a contemporary diary. The origin of the house is equally vague. The present building appears to date from the early 1600s, but the interior ground floor on the east is earlier, possibly dating back to 1431 when it was owned by Sir Edmund Cheney.[22] Probably it originated as a farmhouse because court is an early word for the yard of a farm.[23] The barn to the north east of Cheney Court is also early 1600s. Following the death of Hugh Speke of Hazelbury Manor in 1624 and the succession of his son, George Speke, Cheney Court was rebuilt for George and his wife Margaret Tempest to move into as their residence. There are family crests over the exterior door and decoration in a bedroom of the arms of George Speke and Margaret flanked by cherubs.

The house has considerable aesthetic pretensions.[24] The windows on the left are staggered to light the main staircase, but the windows on the right are a sham, symmetrical with those on the left but unrelated to the internal layout behind.[25] It is possible that both wings may have had staircases at some stage.[26]

The house has considerable aesthetic pretensions.[24] The windows on the left are staggered to light the main staircase, but the windows on the right are a sham, symmetrical with those on the left but unrelated to the internal layout behind.[25] It is possible that both wings may have had staircases at some stage.[26]

5. Coles Farmhouse

Not strictly a medieval manor house, Coles Farmhouse in Alcombe is an ornate Jacobean-style property which occupies a magnificent site looking down the Box valley. The left gable end is marked 1646, the right gable is dated 1685.

Not strictly a medieval manor house, Coles Farmhouse in Alcombe is an ornate Jacobean-style property which occupies a magnificent site looking down the Box valley. The left gable end is marked 1646, the right gable is dated 1685.

|

The house was the creation of Peter Webb, who bought land at Coles and at Rudloe in 1633, possibly from the Hungerford estate.[27] The family owned other parcels of land in Box and Allen’s 1630 map shows an adjacent field belonging to Webb. The origin of the house's name is believed to be Robert Cole in 1362.[28] It is a house of quality built for a country gentleman before the Classical era superseded this style of architecture.

There are still some fine 1600s stone fireplaces inside and a very beautiful room on the ground floor with rich panelling and a plaster ceiling.[29] In a later issue we are going to tell the story of the house which at one stage was called The Falconers. |

|

6. Alcombe Manor

Francis Allen's map of 1630 calls the name of the area Awcon but there is no evidence that a manor house existed there at that time. Indeed, Alcombe is reputed to be a wealthy clothier’s house built in 1641. It does have a much older origin, perhaps medieval, with a small window to the rear of the entrance dating from the 1300s.[30] There is a local anecdote that the house has a medieval entrance hall once used by pilgrims on their way to Glastonbury. It was originally a farmhouse which appears to have been upgraded. |

|

7. Rudloe Manor

The manor house is a Grade II listed building dating from about 1685 but much restored in the course of its history. Rudloe (originally called Ridlaw) Manor had a chequered history of ownership. In 1533 it was held by Robert Leversage, Esquire of Frowmselwood, Somerset who owned the manor of Rudlowe in Box parish and 8 messuages, 100 acres of pasture, 50 acres of meadow, 300 acres of arable land, 20 acres of wood, and 40 acres of gorse and heath in Rudlowe and Boxe, worth £10 yearly.[31] But in March of that year he failed to repay a debt of 500 marks owed to William Button. A year later he was sued by William Dauntsey over land in Stokton.[32] |

In 1589 the manor was owned by Sir Walter Hungerford and in 1629 by Sir Edward Hungerford of Corsham, Commander of the Wiltshire Commonwealth troop in the Civil War.[33] The present Manor house was built by Thomas Goddard and a few medieval windows remain in the building.[34]

|

8. The Old Parsonage

Again not a true manor house but in control of much tithe income, the Old Parsonage House stood in the grounds of the present Box House before it burned down on 6 November 1805. It was a large property built on extensive glebe land, allowed for the vicar's residence.[35] A 1672 description of it says three bays of buildings, with a dove house adjoining to the south side of it, with outlets to gardens and orchards belonging to the said house. Also a stable containing one bay of buildings.[36] With the destruction of the house went its stained glass windows bearing the formidable warning: Remember the four last things - Death, Judgement, Heaven and Hell.[37] |

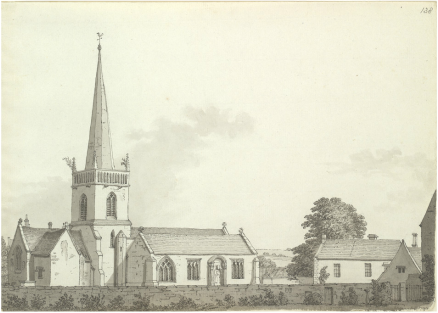

Above Right: Illustration of 1790 appears to show the Old Parsonage chimney on the right (courtesy Box Parish Council).

Below: Box Church and the Old Parsonage (marked as Vicarage) to the west of the church in Francis Allen's map of 1626 (courtesy Wiltshire History Centre).

Below: Box Church and the Old Parsonage (marked as Vicarage) to the west of the church in Francis Allen's map of 1626 (courtesy Wiltshire History Centre).

9. Bayliff's Farm, Wadswick (also called Manor Farm, Wadswick)

|

The manor of Wadswick is ancient. The generally accepted origin of the name Wadswick is the Saxon words, the dairy farm of Waeddi and the first recorded reference is Wadeswica in a charter of the 1100s in the British Museum.[38] There are several later references to the area including one in about 1190 when Walter Croke of Hazelbury gifted to Bradenstoke Priory all the tithes of my men of Haselbury and of Wadswick.[39]

We can see that by Tudor and Stuart times the area had been substantially developed with the farmhouse and farmworkers cottages. Right: Extract from Francis Allen's 1630 map showing the lane and properties at Wadswick (courtesy Wiltshire History Centre). |

10. Shockerwick House

Outside the modern parish but part of Hugh Speke's property was the manor of Shockerwick. Francis Allen has drawn the property just off his map but not given any details about it. The 1630 map replicates the picture of the house.

Outside the modern parish but part of Hugh Speke's property was the manor of Shockerwick. Francis Allen has drawn the property just off his map but not given any details about it. The 1630 map replicates the picture of the house.

References

[1] www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/england/wiltshire/box and Historic Buildings

[2] Nathaniel J Hone, The Manor and Manorial Records, 1971, Kennikat Press, p.37

[3] Pamela M Slocombe, Medieval Houses of Wiltshire, 1992, Wiltshire Buildings Record, p.63

[4] Pamela M Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, 1989, Wiltshire Building Record, p.16

[5] Pamela M Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, p.16

[6] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, 1970, David & Charles, p.17

[7] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.92

[8] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol I, p.144

[9] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.91-3

[10] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.132 and 296-8

[11] JH Bettey, Suppression of Monasteries in the West Country, 1989, Alan Sutton, p.135

[12] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.183-4

[13] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.172 and 304-8

[14] Pamela Slocombe, Survey of Countryside Treasures, Box, 1969, notes in Wiltshire History Centre, p.15

[15] Sir William Addison, The Old Roads of England, 1980, BT Batsford Ltd, p.92

[16] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.190

[17] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, p.57

[18] We will later publish the Story of Tudor Ashley

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[20] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, p.59

[21] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, 1987, p.7 reverse

[22] WI leaflet and Historic Buildings

[23] Pamela M Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, p.16

[24] The Royal Commission on Historic Monuments described the house in 1992 as: a provincial builder’s attempt to build a house to the compact, rectangular double-pile plan that was becoming increasingly widespread during the 17th century but whose acceptance throughout the country was affected by the strength of existing building traditions.

[25] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, p.8

[26] See Historic Buildings

[27] PM Slocombe, Coles Farm, Alcombe, Box, 1985, Wiltshire History Centre

[28] JEB Gover, Allen Mawer, and FM Stenton, The Placenames of Wiltshire, 1939, Cambridge University Press, p.85

[29] See Historic Buildings

[30] Brig E Felton-Falkner, Wormcliffe House, Box, 1942, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Vol 49, p.534

[31] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol. XXVIII

[32] The National Archives DD\BR\Wt/11

[33] Pamela Slocombe, Survey of Countryside Treasures, Box, 1969, notes in Wiltshire History Centre

[34] PSA Register 1984, Wiltshire History Centre

[35] Pamela M Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, 1989, Wiltshire Building Record, p.58

[36] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, p.28

[37] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, p.58

[38] JEB Gover, Allen Mawer, and FM Stenton, The Placenames of Wiltshire, 1939, Cambridge University Press, p.85

[39] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, p.49 and 253