Thomas Goddard of Rudloe (part 2) Jonathan Parkhouse December 2020

This is part 2 of Jonathan’s research into the land held by the Goddard family in Rudloe. In the previous article he focussed on the family of Thomas Goddard, and the field-book in which he kept a record of the land they owned. In this article he looks at some newly discovered documentation for the Rudloe estate, and attempts to reconstruct the landscape described in these eighteenth century documents.

|

The text transcriptions and tables which accompany this article are available as a separate downloadable file right.

|

| ||||||

An oath, a paper and a parchment

Within a few weeks of submitting the previous article about the Goddards at Rudloe to the editor of Box People and Places, along with what the author thought would be a final version of the present article, a further set of documents came to light, held in a private collection and previously entirely unknown. I am most grateful to the owner who provided very detailed photographs. The discovery of these ‘new’ documents provides fresh information about the Goddard estate at Rudloe, and the account has been re-written accordingly.

There are three ‘new’ documents, all bundled together, apparently produced as evidence in litigation in 1821. The first is an affidavit, or testimony, by Edward Lee, then living at West Compton, Berkshire, dated 31st October 1821, sworn before George Ryley, Master Extraordinary in Chancery, at Aldbourne, Wiltshire. This affirms that his late father, also Edward Lee, had rented the Rudloe estate from Thomas Goddard, and subsequently, after Thomas's death, from Thomas's brother Ambrose. Edward Lee senior continued to rent the estate until around 1787, by which time Ambrose Goddard had sold it to Thomas Beames. At this date Edward Lee junior was aged about 26 and residing with his father. Edward Lee junior was sole executor for his father, who died in March 1797. At the request of a firm of solicitors in Chippenham, Edward Lee had made a search of his late father's papers for old surveys or terriers, and discovered two documents, one on paper, dated 1722, and the other on parchment, dated 1755. He states that the marginal notes and alterations on both documents were in his father's handwriting, having been made either during the period when he rented the Goddard estate, or previously when he had been the estate manager.

The interest in this affidavit, apart from providing context for the two earlier documents attached to it, is the additional information it gives us about the Goddard estate; that it was first managed and then rented by Lee until 1787, and that it had been sold to Thomas Beames (this must have been at some point between 1770 and 1787). The Lee family seem to have retained an interest in the area even after the elder Edward Lee’s surrender of his tenancy in 1787, as an Edward Lee (possibly the Edward Lee of the affidavit) owned land in Rudloe at the time of the 1838 Tithe Apportionment.[1]

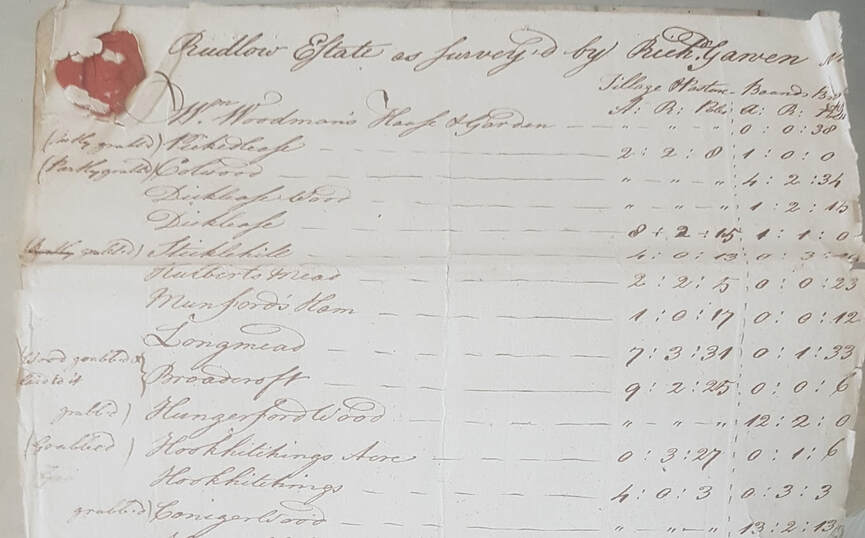

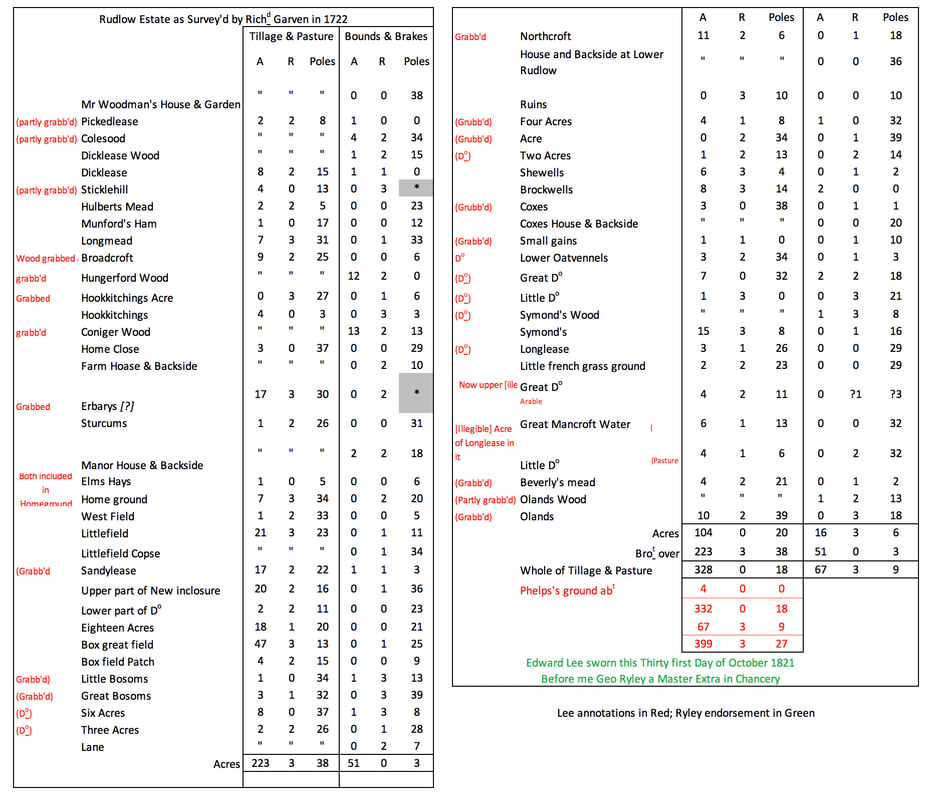

The second document is that identified in the affidavit as being on paper, and is a survey made by Richard Garven or Gawen in 1722. (Garven had surveyed Hartham House, then owned by the Duckett family but adjacent to Hartham Park, the estate of another member of the Goddard family, in 1716).[2] This document gives two measurements for each land parcel; an area of "Tillage and pasture' and another for 'Bounds and Brakes'; the two areas have not been added together. There are also annotations by Edward Lee senior, mainly to indicate which had been 'grabbed' or ‘grubbed’; the meaning of the term here is not entirely clear - it should mean 'dug/ dug up' (ie arable?) although the areas thus described include areas which were woodland (and which continued to be woodland after the eighteenth century).

Within a few weeks of submitting the previous article about the Goddards at Rudloe to the editor of Box People and Places, along with what the author thought would be a final version of the present article, a further set of documents came to light, held in a private collection and previously entirely unknown. I am most grateful to the owner who provided very detailed photographs. The discovery of these ‘new’ documents provides fresh information about the Goddard estate at Rudloe, and the account has been re-written accordingly.

There are three ‘new’ documents, all bundled together, apparently produced as evidence in litigation in 1821. The first is an affidavit, or testimony, by Edward Lee, then living at West Compton, Berkshire, dated 31st October 1821, sworn before George Ryley, Master Extraordinary in Chancery, at Aldbourne, Wiltshire. This affirms that his late father, also Edward Lee, had rented the Rudloe estate from Thomas Goddard, and subsequently, after Thomas's death, from Thomas's brother Ambrose. Edward Lee senior continued to rent the estate until around 1787, by which time Ambrose Goddard had sold it to Thomas Beames. At this date Edward Lee junior was aged about 26 and residing with his father. Edward Lee junior was sole executor for his father, who died in March 1797. At the request of a firm of solicitors in Chippenham, Edward Lee had made a search of his late father's papers for old surveys or terriers, and discovered two documents, one on paper, dated 1722, and the other on parchment, dated 1755. He states that the marginal notes and alterations on both documents were in his father's handwriting, having been made either during the period when he rented the Goddard estate, or previously when he had been the estate manager.

The interest in this affidavit, apart from providing context for the two earlier documents attached to it, is the additional information it gives us about the Goddard estate; that it was first managed and then rented by Lee until 1787, and that it had been sold to Thomas Beames (this must have been at some point between 1770 and 1787). The Lee family seem to have retained an interest in the area even after the elder Edward Lee’s surrender of his tenancy in 1787, as an Edward Lee (possibly the Edward Lee of the affidavit) owned land in Rudloe at the time of the 1838 Tithe Apportionment.[1]

The second document is that identified in the affidavit as being on paper, and is a survey made by Richard Garven or Gawen in 1722. (Garven had surveyed Hartham House, then owned by the Duckett family but adjacent to Hartham Park, the estate of another member of the Goddard family, in 1716).[2] This document gives two measurements for each land parcel; an area of "Tillage and pasture' and another for 'Bounds and Brakes'; the two areas have not been added together. There are also annotations by Edward Lee senior, mainly to indicate which had been 'grabbed' or ‘grubbed’; the meaning of the term here is not entirely clear - it should mean 'dug/ dug up' (ie arable?) although the areas thus described include areas which were woodland (and which continued to be woodland after the eighteenth century).

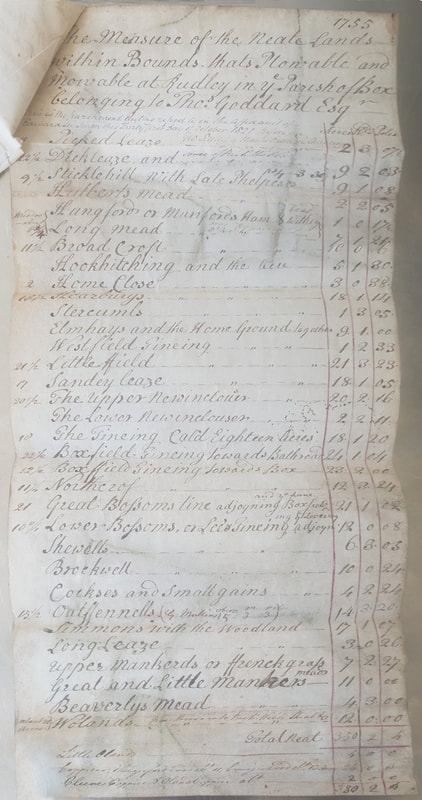

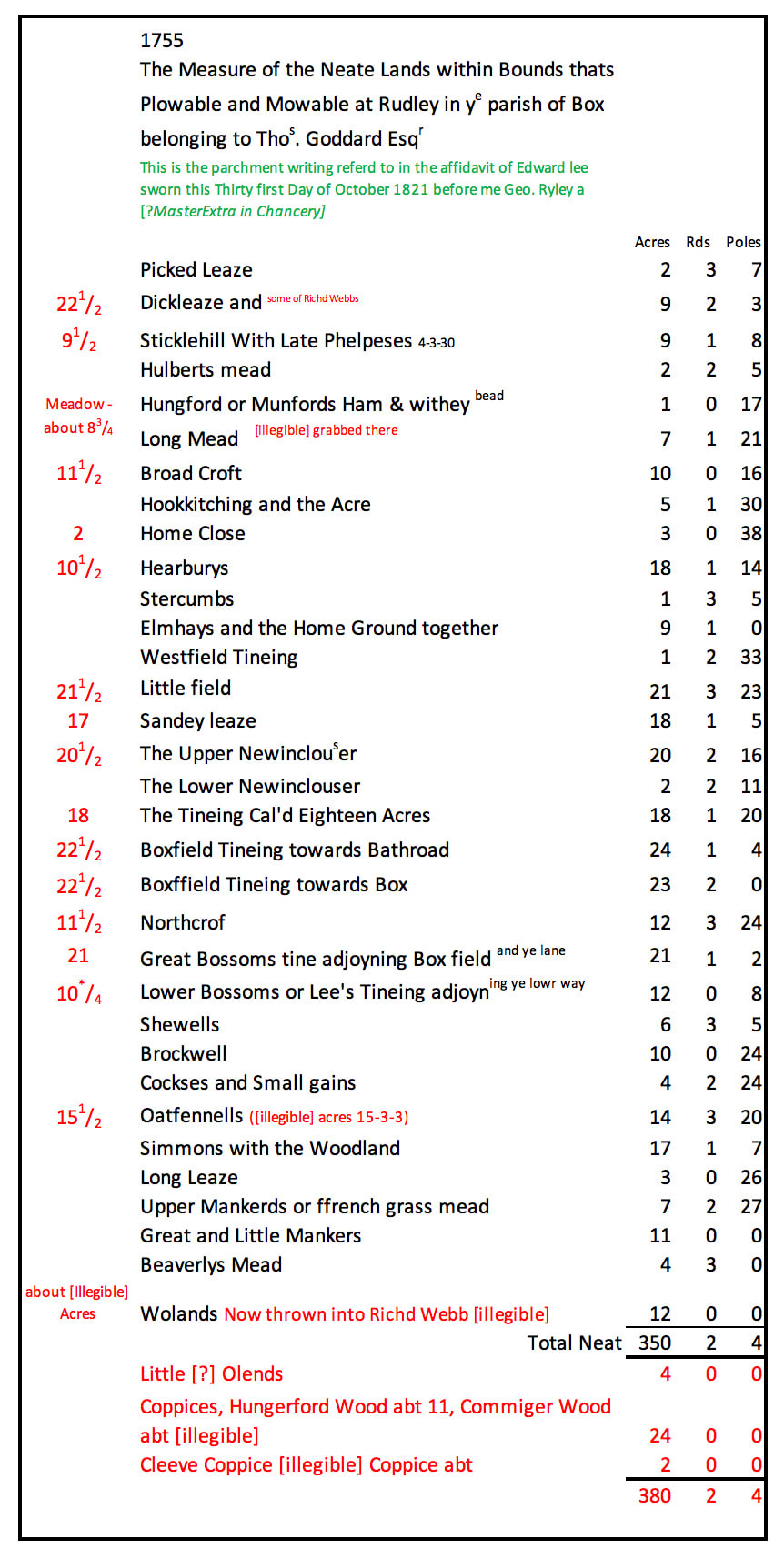

The third document is that described in the affidavit as being on parchment and dated 1755: "The Measure of the Neate Lands within Bounds thats Plowable and Mowable at Rudley in ye parish of Box belonging to Thos. Goddard Esqr". This gives a single measurement of area for each land parcel. The list of land parcels is shorter than that of the 1722 survey and less extensive than the estate described in the Goddard field-book. Woodland, for the most part, is not included. Additions by Edward Lee mainly consist of revised figures for the areas of some of the land parcels, rounded to the nearest half acre, and the addition at the end of the document of measurements for the woodland. We may conjecture that the 1755 survey was occasioned either by the death of Thomas Goddard's father that year, in order to provide an inventory of his estate, or was commissioned by Thomas upon his inheritance of the estate.

Both the 1722 and the 1755 documents are endorsed by George Ryley to affirm that they are the documents referred to in the affidavit.

Both the 1722 and the 1755 documents are endorsed by George Ryley to affirm that they are the documents referred to in the affidavit.

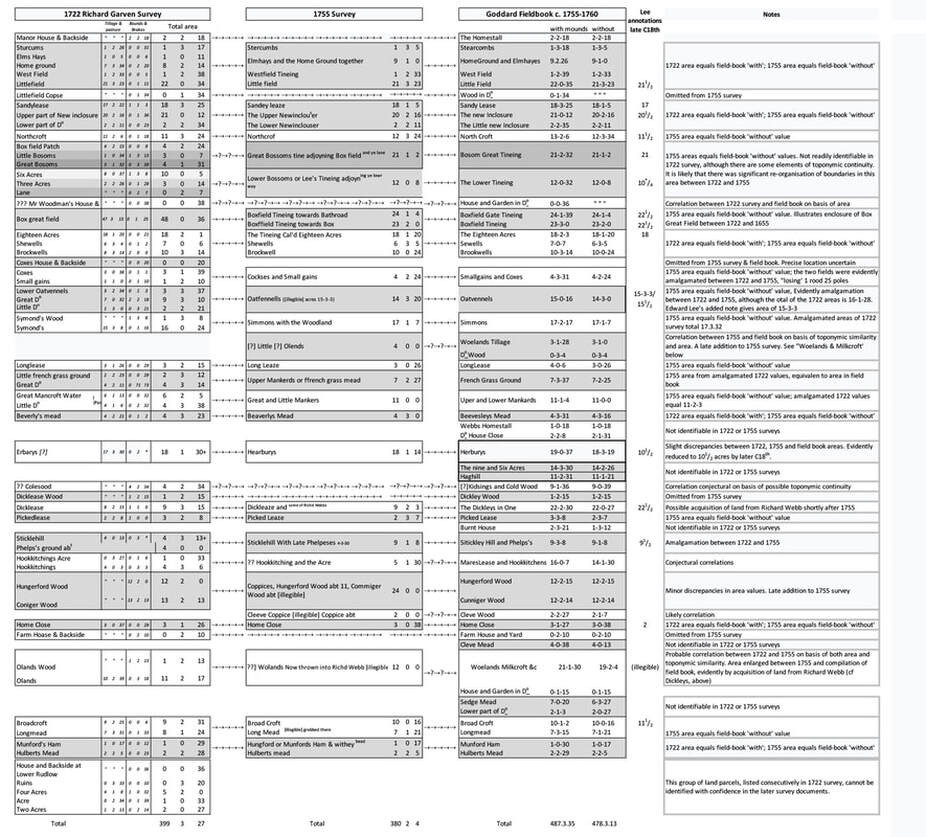

Comparison of the 1722 and 1755 surveys with the entries in the field-book shows numerous differences between the three documents, tabulated in detail in the concordance shown here. The land parcels listed in the 1722 survey total just under 400 acres, those in the 1755 survey 380 acres, and those in the field-book 478 acres. The first two seem to be recording approximately the same area, although there are more entries, and thus more individual land parcels in the 1722 survey than in the 1755 survey. In some instances this will be down to amalgamation of land parcels. There are also more buildings recorded in 1722 than in 1755. The third survey, recorded in the field book, appear to indicate an extension of the estate under Thomas Goddard. Since, as we shall see, the internal evidence of the field-book shows that it must have been compiled by 1761, Thomas seems to have lost little time in extending the estate. Amongst the mid-eighteenth century acquisitions appear to have been Woelands Tillage, Nine and Six acres, Hag Hill, Cleve Mead and Sedge Mead.

Where land parcels are recorded in all three documents, the 'with mounds' areas in the fieldbook are often derived from the sum of the two measurements in the 1722 survey (although often with a difference of a single pole either way), whilst the 'without mounds' areas are in a majority of cases derived from the 1755 survey. We shall discuss the significance of these later, but we may presume that Thomas Goddard used both documents (or at least a copy of the information contained within them) to compile his field-book, and that he knew at least some of the background to the surveys and perhaps the methodologies employed which resulted in two sets of measurements.

We therefore have three eighteenth century documents which all describe a broadly similar area. In the following account we shall identify these as the 1722 survey, the 1755 survey, and the field-book terrier, which must date to between 1755 and 1761.

Where land parcels are recorded in all three documents, the 'with mounds' areas in the fieldbook are often derived from the sum of the two measurements in the 1722 survey (although often with a difference of a single pole either way), whilst the 'without mounds' areas are in a majority of cases derived from the 1755 survey. We shall discuss the significance of these later, but we may presume that Thomas Goddard used both documents (or at least a copy of the information contained within them) to compile his field-book, and that he knew at least some of the background to the surveys and perhaps the methodologies employed which resulted in two sets of measurements.

We therefore have three eighteenth century documents which all describe a broadly similar area. In the following account we shall identify these as the 1722 survey, the 1755 survey, and the field-book terrier, which must date to between 1755 and 1761.

Reconstructing Eighteenth Century Rudloe

In Part 1 we noted that in all likelihood there had originally been a map accompanying the list of fields in Thomas Goddard’s field-book which constituted the Goddard’s Rudloe estate; unfortunately the sole surviving trace is the discolouration from the paste which originally held the map in place within Thomas Goddard’s field-book. Although the loss of what would have been the earliest map of Rudloe is frustrating, it is nevertheless possible to attempt a partial reconstruction of the missing map. The first task is to examine other historic mapping. Rudloe did not form part of the Speke estate and only the southernmost part of the area under consideration is included on the Allen maps of 1626 and 1630, thus we can only speculate about the rest of Rudloe’s 17th century fieldscape and the date and process of enclosure of the common fields. The absence of an Enclosure Act relating to Box makes it likely that enclosure at Rudloe, as was the case in the rest of Box parish, was a piecemeal affair rather than a single episode. The earliest detailed map of Rudloe which still survives is the 1832 Northey map of Hazelbury Box and Ditteridge manors,[3] created a few years before the Tithe Map; the latter (1838) shows no substantial change in the Rudloe field boundaries since the 1832 map (although there are minor differences in the precise delineations of boundaries and roads) and indeed the field numbering on the 1832 map and the Tithe map is the same.

In Part 1 we noted that in all likelihood there had originally been a map accompanying the list of fields in Thomas Goddard’s field-book which constituted the Goddard’s Rudloe estate; unfortunately the sole surviving trace is the discolouration from the paste which originally held the map in place within Thomas Goddard’s field-book. Although the loss of what would have been the earliest map of Rudloe is frustrating, it is nevertheless possible to attempt a partial reconstruction of the missing map. The first task is to examine other historic mapping. Rudloe did not form part of the Speke estate and only the southernmost part of the area under consideration is included on the Allen maps of 1626 and 1630, thus we can only speculate about the rest of Rudloe’s 17th century fieldscape and the date and process of enclosure of the common fields. The absence of an Enclosure Act relating to Box makes it likely that enclosure at Rudloe, as was the case in the rest of Box parish, was a piecemeal affair rather than a single episode. The earliest detailed map of Rudloe which still survives is the 1832 Northey map of Hazelbury Box and Ditteridge manors,[3] created a few years before the Tithe Map; the latter (1838) shows no substantial change in the Rudloe field boundaries since the 1832 map (although there are minor differences in the precise delineations of boundaries and roads) and indeed the field numbering on the 1832 map and the Tithe map is the same.

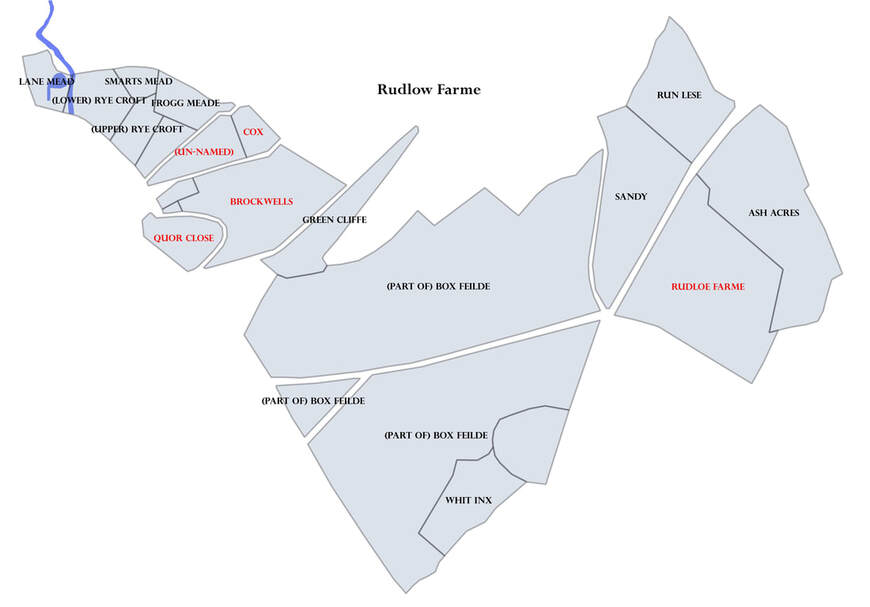

Digitised extract of Francis Allen’s” Plott and description of the Mannors of Haiselbury Box and Ditchridge. The greater part of Rudlow left out” (1630). Sir Edward Hungerford’s lands in red; Run Lese, Sandy and Ash Acres also appear to have been part of Rudloe Farm at this time. Only that part of the Allen map which overlaps with Thomas Goddard’s estate is shown.

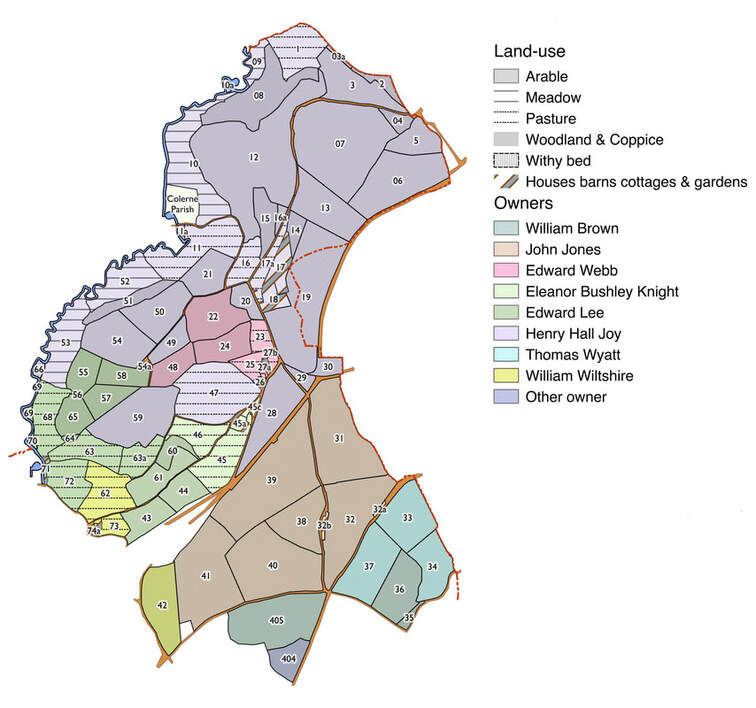

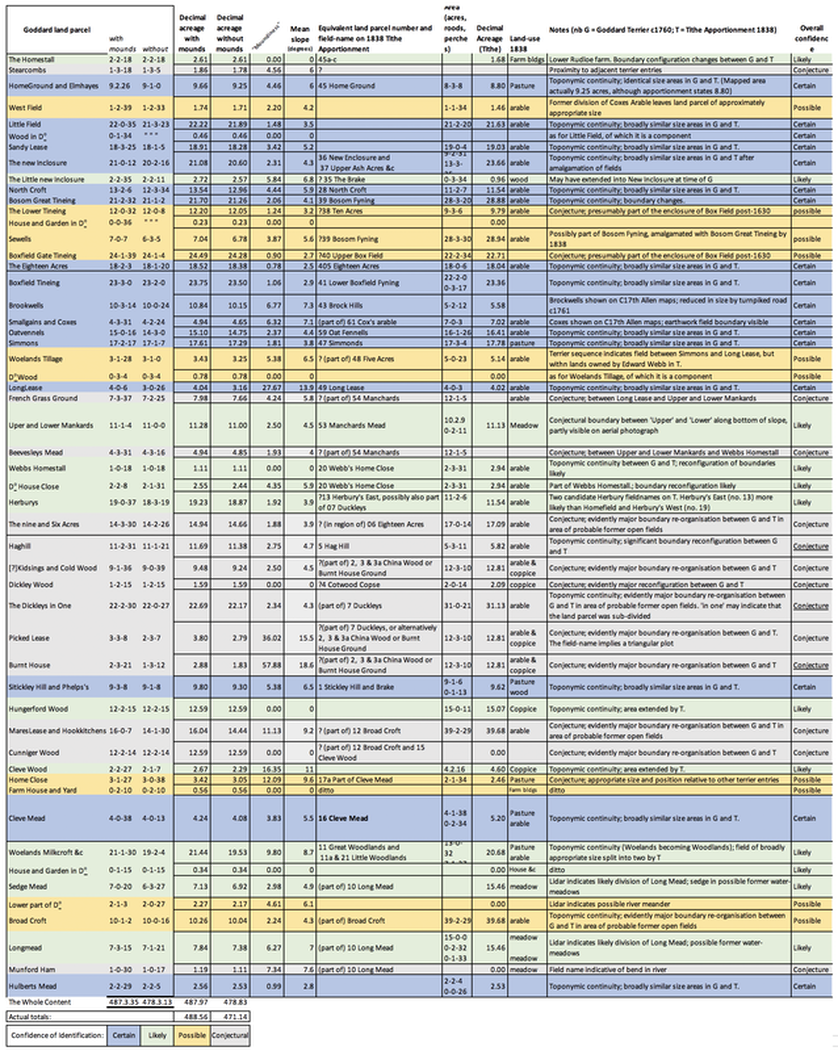

The Tithe apportionment [4] provides fieldnames and acreages as well as details of owners and tenants and information about land use, and on this basis one may attempt to identify some of the land parcels in the Goddard documents. However, attempts to match fields in the Goddard surveys with fields of either the same name or the same area within the parts of the Tithe apportionment relating to land in Rudloe meet with only partial success. A few entries in the terrier fit relatively closely with those in the Apportionment: thus Little Field (land parcel 31 at 21a-2r-20p in the apportionment), Sandy Leaze (land parcel 32, 19-0-4), or Simmonds (parcel 47, 17-3-4) are close enough in size to be readily identifiable, and indeed Sandy is shown on the Allen maps. On the other hand there are several instances where an equivalent field name in the Goddard terrier equates with one in the apportionment, but the area is significantly different, for example Hag Hill, 11-1-21 in the Goddard field-book but not listed in 1722 or 1755, is roughly half the size (5-3-11) in the apportionment (land parcel 5) and Broad Croft (9-2-31 in 1722; 10-0-16 in 1755 and the field-book) has almost quadrupled in area in the apportionment (land parcel 12: 39-2-29). About half the fields in the Goddard terrier have names which do not occur in the Tithe apportionment. This disparity between the Goddard documents and the Tithe apportionment should not come as a surprise; during the 18th and 19th centuries agricultural improvement was taken up enthusiastically, and fields would often have been amalgamated or re-organised. Where a fieldname matches, wholly or in part, but there is a significant disparity in size, we may legitimately draw the conclusion that the fieldname has remained in roughly the same location, even if the field boundaries have not.

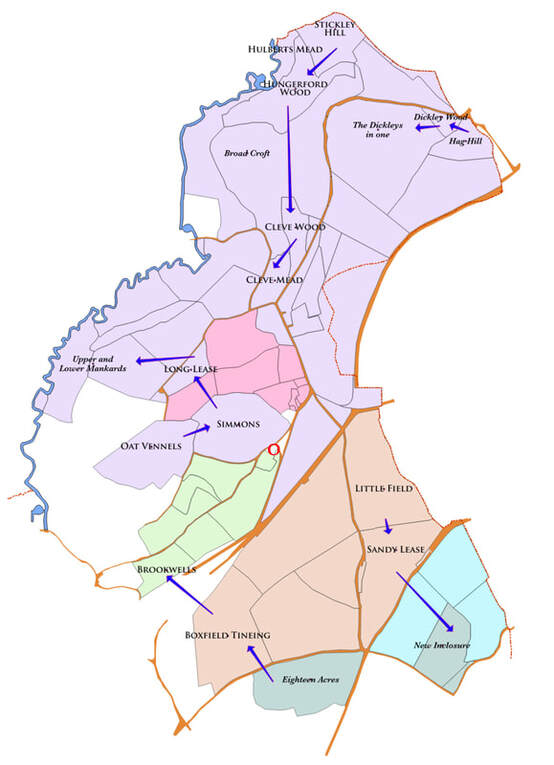

Initial 'certain’ (capitals) and ‘likely’ (italic) identifications of fields in the Goddard field-book, using the 1838 Tithe map, and showing general sequence of citation from the presumed point of origin 0 at Lower Rudloe Farm. Colours show ownership in 1838, as per Tithe map extract above. The transcripts of the 1722 and 1755 surveys demonstrate that the fields were listed in a different order, but still indicative of a perambulation around the estate, whether undertaken on the ground or in the mind’s eye.

Nevertheless, plotting those fields in the Goddard field-book terrier which match those in the apportionment indicates that, as with the Swindon terriers, the sequence in which the fields are listed is broadly systematic, moving around the estate in the order which the owner might have adopted on a tour of inspection. The orders of citation in the 1722 and 1755 surveys, whilst differing from that in the field-book,[5] also seem to reflect actual perambulations. One may therefore hazard a guess as to the likely general areas in which the ‘missing’ fields might be found. Whilst the 1722 and 1755 surveys start near the northeastern end of the estate, the field-book entries start from The Homestall, evidently Lower Rudloe Farm, suggesting that this was the principal set of farm buildings within the Goddard estate at Rudloe following the sale of Rudloe Manor at the end of the 17th century. It is likely that Thomas Goddard senior built (or re-built) Lower Rudloe Farm, which is mid 18th century and incorporates a (reset) datestone of 1749.[6]

It can also be observed that some of the land-holdings shown on the 1838 Tithe apportionment do not appear to have been part of Thomas Goddard’s estate; thus the lands owned in 1838 by Edward Webb,[7] Edward Lee and William Wiltshire are not amongst those identifiable in the Goddard terrier. Although there had very clearly been changes in land ownership between the mid-eighteenth century and 1838, some continuity in the extent of individual estates is likely even if they had changed hands. If one accepts the hypothesis that the Goddard fields are likely to be found amongst a limited number of the later landholdings, this may restrict the areas in which we should be attempting to locate them. Any reconstruction must also avoid isolating fields of other owners as enclaves within Goddard lands; all non-Goddard land would need to be accessible, either from a road or track, or from other fields in the same ownership.

Some evidence for former field boundaries is visible on aerial photographs, both those readily available online and the historic sets of aerial photographs held by Historic England and the Wiltshire Historic Environment Record.[8] Visibility of linear features will be variable; not all will necessarily be field boundaries, and those that are will often be difficult to date. The lidar (aerial laser scanning) data released by the Environment Agency is also useful, although subject to similar limitations as aerial photographs.

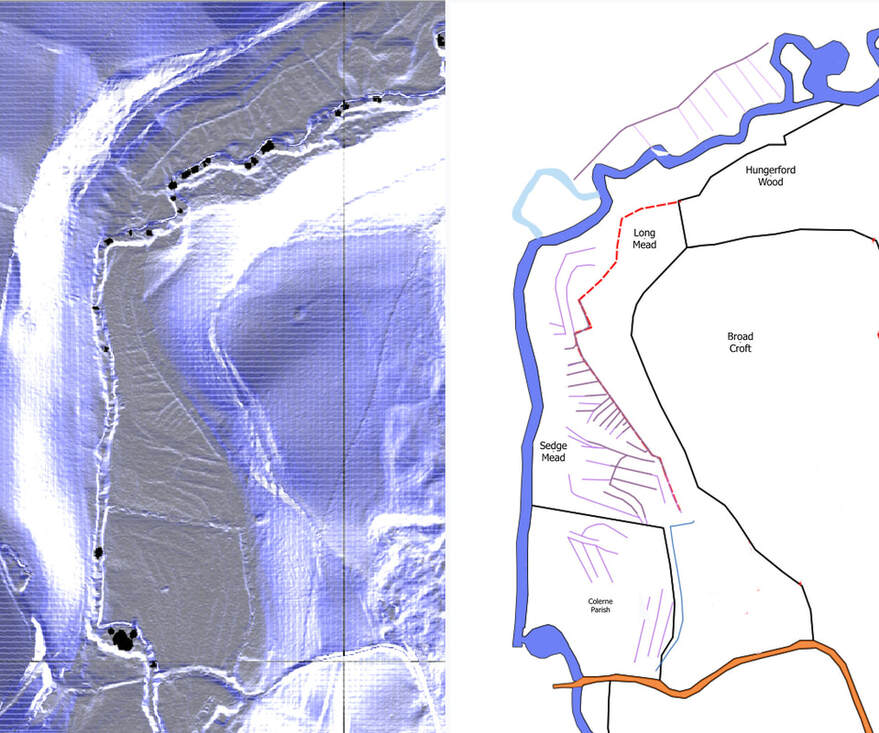

Lidar enables us to identify Sedge Mead, which features in the field-book, with reasonable confidence. Long Mead (8-1-24 in 1722, 7-1-21 in 1755 and the field-book) is clearly smaller than the Long Mead in the Tithe apportionment (15-0-0), but if added to Sedge Mead (6-3-27) the discrepancy is relatively small. Inspection of the Lidar data shows a prominent ditch at the bottom of the hill slope which divides the Long Mead of the tithe map into two almost equal areas of around 7 acres (Figure 9). The low-lying part next to the By Brook shows a prominent series of short ditches running off the boundary ditch, which are likely to be the remains of either a substantial network of drains or even a water meadow. Without the drainage the low-lying area would have been a suitable habitat for sedge.[9]

Some evidence for former field boundaries is visible on aerial photographs, both those readily available online and the historic sets of aerial photographs held by Historic England and the Wiltshire Historic Environment Record.[8] Visibility of linear features will be variable; not all will necessarily be field boundaries, and those that are will often be difficult to date. The lidar (aerial laser scanning) data released by the Environment Agency is also useful, although subject to similar limitations as aerial photographs.

Lidar enables us to identify Sedge Mead, which features in the field-book, with reasonable confidence. Long Mead (8-1-24 in 1722, 7-1-21 in 1755 and the field-book) is clearly smaller than the Long Mead in the Tithe apportionment (15-0-0), but if added to Sedge Mead (6-3-27) the discrepancy is relatively small. Inspection of the Lidar data shows a prominent ditch at the bottom of the hill slope which divides the Long Mead of the tithe map into two almost equal areas of around 7 acres (Figure 9). The low-lying part next to the By Brook shows a prominent series of short ditches running off the boundary ditch, which are likely to be the remains of either a substantial network of drains or even a water meadow. Without the drainage the low-lying area would have been a suitable habitat for sedge.[9]

Sedge Mead and Long Mead. (Left) Lidar data: Digital Terrain Model (DTM), 1m resolution (2005); Slope Gradient merged with hill-shading (30o Altitude, 2o azimuth); (Right) Analytical interpretation, showing possible water-meadow remnants and putative boundary (dashed red line) between Long Mead and Sedge Mead. Field boundaries as per 1838 Tithe plan. Contains Environment Agency Information: © Environment Agency and database right 2020

Both lidar and aerial photographs show a possible meander of the By Brook on the Colerne side. It appears to truncate a series of faintly-visible features which may be vestiges of the ditches of another water meadow on the Colerne bank, in which case the meander may have been carrying water whilst the water meadow was still extant. If this is so, the area within the meander could be the lower part of Sedge Mead described in the field-book.

Although the Rudloe terrier in the field-book is undated, some internal evidence for the date of the survey is provided by the field called Brookwells, identified as Brockwells on the Allen maps and Brock Hills on the tithe apportionment.[10] The field-name refers to a small spring near the bottom of the field. In 1626 the area is given as 11-1-23, in 1722 10-3-14, in 1755 and the field-book as 10-0-24, but in 1838 the size has fallen to 5-2-12. The reason for the reduction in size is the construction of the turnpike road from Hartham through to Bath for which the parliamentary Act had been enacted in 1756-7 and which was completed by 1761.[11] The Goddard survey must therefore have been undertaken before the turnpike reduced the size of Brookwells. The turnpike construction also reduced the size of the field called Home Ground, and the changes in area recorded in the various documentary sources are consistent with this.

The fieldnames also provide clues as to the terrain they occupied. Several relate to grassland, using elements that had specific meanings. Five of the Goddard land parcels contain the element ‘mead’. Cleve Mead and Hulbert’s Mead are identifiable from the Tithe apportionment, and if we accept the identification of Sedge Mead as a part of Long Mead, the only ‘missing’ mead is Beverly’s/ Beaverlys/ Beevesley’s Mead. This cannot be identified with any certainty. ‘Mead’ is clearly a meadow, often along the edge of a watercourse (the early 17th-century Allen maps show a continuous series of mead field-names along the By Brook). These were grazed, usually for short periods, and cut for hay. Pasture was not cut for hay and thus could be grazed all year. The extract from the Tithe map (see above) shows that the meadows within Rudloe in the Tithe apportionment were along the By Brook, although the fields adjacent to Weavern Mill are described as pasture. Leys were fields sown with grass for a few years before reverting to arable, but Lease was a term sometimes used for a meadow, as was leasow (from Old English læswe ‘at the pasture’) , which could be used for either pasture or meadow, and by the 16th century came to be a general term for an enclosure or even for an arable field (elsewhere in Box there was an Oat Leaze).[12] Another grassland placename element is ham, an Old English word for enclosure, but particularly a narrow strip of land in the bend of a river. Munford Ham, situated between two ‘mead’ fieldnames, must therefore be beside the By Brook.

Tyning/Tineing is a term for a fenced enclosure (derived from ‘tine’, a stake). The Goddard fields with a Tineing element in their name occur close together in the terrier, apparently focussed around present day Boxfields, and this concentration suggests enclosure of the former open fields. Examination of the Allen maps shows that this is indeed the case; in 1626/1630 this area was part of Box Feilde, one of the open fields. Another fieldname that refers to a field boundary is Hayes; thus Elmhayes was a plot of land with elm trees along the hedge – a very common sight before the 1960s when the loss of so many hedgerow elms had a significant impact on the English landscape.

The first part of ‘Smallgains and Coxes’ suggests a field which was not particularly profitable; fieldnames of this type (one thinks of the relatively common ‘labour in vain’) are not infrequent; there are some dozen ‘Small Gains’ in Wiltshire [13] and indeed one of Goddard’s fields in Swindon bore the same name. The approximate position can be suggested on the basis of the ‘Cox’s Arable’ name in the tithe apportionment, but better evidence comes from the 1626 & 1630 Allen maps which show Cox as a small field of 1-3-35 next to Brockwells (Brookwells in the Goddard field-book); ‘Small Gains’ must have been the immediately adjacent field. The two were listed separately in 1722 and must have been amalgamated before 1755, when they are recorded as a single unit. The eastern side of the field (that which was ‘Smallgains’ rather than ‘Coxes’) rises to a steep bank; it may have been awkward to work. The 1722 survey also lists separately ‘Coxes House and Backside’. This must be the building shown within Cox on the Allen maps, next to the lane leading towards Lower Rudloe Farm. The possible remnants of one wall of the building survive along the boundary of the lane at grid reference ST 8364 6978, where the hedge adjacent to Coxes has a distinctly stony core for a length of several metres, whilst the footpath here is markedly more stony.

‘Woelands Tillage’ is also a name which might appear to be indicative of a field which gave the farmer little financial reward, although the ‘Woe-’ element is as likely to be from Old English ‘Wōh’, meaning crooked,[14] and thus refer to the field shape rather than its inherent economic potential. The ‘Tillage’ part of the name indicates an arable field. In fact ‘Woelands’ occurs twice in Goddard’s Rudloe estate, with a ‘Woelands Milkcroft &c’ with a house and garden adjacent. Neither field can be identified with absolute certainty, and neither of the fields identified as Woelands on our reconstructed map (below) can be described as crooked. However, that identified here as Woelands and Milkcroft (a single land parcel in the Goddard terrier) consisted of two fields in 1838, one of which was L-shaped (i.e. crooked), and it is possible that the two fields were listed as one in the Goddard survey; the ‘&c’ in the field-book entry suggests that the land parcel was sub-divided in some way. The 1722 survey includes a small area called Olands Wood next to the entry for Olands (which had become a single entry Wolands by 1755).

Another name which describes the field’s shape is Picked Lease. ‘Picked’ (to rhyme with ‘wicked’) refers to a ‘peak’ or ‘pike’, a common description for a triangular piece of land.[15] Its whereabouts cannot be pinpointed with certainty although it must have been in the northern part of Rudloe. Thomas Goddard owned fields called Picked Mead and Picked Marsh on his Swindon estate; Edward Smith’s map, pasted into the field-book, shows that both were triangular plots.

Although the Rudloe terrier in the field-book is undated, some internal evidence for the date of the survey is provided by the field called Brookwells, identified as Brockwells on the Allen maps and Brock Hills on the tithe apportionment.[10] The field-name refers to a small spring near the bottom of the field. In 1626 the area is given as 11-1-23, in 1722 10-3-14, in 1755 and the field-book as 10-0-24, but in 1838 the size has fallen to 5-2-12. The reason for the reduction in size is the construction of the turnpike road from Hartham through to Bath for which the parliamentary Act had been enacted in 1756-7 and which was completed by 1761.[11] The Goddard survey must therefore have been undertaken before the turnpike reduced the size of Brookwells. The turnpike construction also reduced the size of the field called Home Ground, and the changes in area recorded in the various documentary sources are consistent with this.

The fieldnames also provide clues as to the terrain they occupied. Several relate to grassland, using elements that had specific meanings. Five of the Goddard land parcels contain the element ‘mead’. Cleve Mead and Hulbert’s Mead are identifiable from the Tithe apportionment, and if we accept the identification of Sedge Mead as a part of Long Mead, the only ‘missing’ mead is Beverly’s/ Beaverlys/ Beevesley’s Mead. This cannot be identified with any certainty. ‘Mead’ is clearly a meadow, often along the edge of a watercourse (the early 17th-century Allen maps show a continuous series of mead field-names along the By Brook). These were grazed, usually for short periods, and cut for hay. Pasture was not cut for hay and thus could be grazed all year. The extract from the Tithe map (see above) shows that the meadows within Rudloe in the Tithe apportionment were along the By Brook, although the fields adjacent to Weavern Mill are described as pasture. Leys were fields sown with grass for a few years before reverting to arable, but Lease was a term sometimes used for a meadow, as was leasow (from Old English læswe ‘at the pasture’) , which could be used for either pasture or meadow, and by the 16th century came to be a general term for an enclosure or even for an arable field (elsewhere in Box there was an Oat Leaze).[12] Another grassland placename element is ham, an Old English word for enclosure, but particularly a narrow strip of land in the bend of a river. Munford Ham, situated between two ‘mead’ fieldnames, must therefore be beside the By Brook.

Tyning/Tineing is a term for a fenced enclosure (derived from ‘tine’, a stake). The Goddard fields with a Tineing element in their name occur close together in the terrier, apparently focussed around present day Boxfields, and this concentration suggests enclosure of the former open fields. Examination of the Allen maps shows that this is indeed the case; in 1626/1630 this area was part of Box Feilde, one of the open fields. Another fieldname that refers to a field boundary is Hayes; thus Elmhayes was a plot of land with elm trees along the hedge – a very common sight before the 1960s when the loss of so many hedgerow elms had a significant impact on the English landscape.

The first part of ‘Smallgains and Coxes’ suggests a field which was not particularly profitable; fieldnames of this type (one thinks of the relatively common ‘labour in vain’) are not infrequent; there are some dozen ‘Small Gains’ in Wiltshire [13] and indeed one of Goddard’s fields in Swindon bore the same name. The approximate position can be suggested on the basis of the ‘Cox’s Arable’ name in the tithe apportionment, but better evidence comes from the 1626 & 1630 Allen maps which show Cox as a small field of 1-3-35 next to Brockwells (Brookwells in the Goddard field-book); ‘Small Gains’ must have been the immediately adjacent field. The two were listed separately in 1722 and must have been amalgamated before 1755, when they are recorded as a single unit. The eastern side of the field (that which was ‘Smallgains’ rather than ‘Coxes’) rises to a steep bank; it may have been awkward to work. The 1722 survey also lists separately ‘Coxes House and Backside’. This must be the building shown within Cox on the Allen maps, next to the lane leading towards Lower Rudloe Farm. The possible remnants of one wall of the building survive along the boundary of the lane at grid reference ST 8364 6978, where the hedge adjacent to Coxes has a distinctly stony core for a length of several metres, whilst the footpath here is markedly more stony.

‘Woelands Tillage’ is also a name which might appear to be indicative of a field which gave the farmer little financial reward, although the ‘Woe-’ element is as likely to be from Old English ‘Wōh’, meaning crooked,[14] and thus refer to the field shape rather than its inherent economic potential. The ‘Tillage’ part of the name indicates an arable field. In fact ‘Woelands’ occurs twice in Goddard’s Rudloe estate, with a ‘Woelands Milkcroft &c’ with a house and garden adjacent. Neither field can be identified with absolute certainty, and neither of the fields identified as Woelands on our reconstructed map (below) can be described as crooked. However, that identified here as Woelands and Milkcroft (a single land parcel in the Goddard terrier) consisted of two fields in 1838, one of which was L-shaped (i.e. crooked), and it is possible that the two fields were listed as one in the Goddard survey; the ‘&c’ in the field-book entry suggests that the land parcel was sub-divided in some way. The 1722 survey includes a small area called Olands Wood next to the entry for Olands (which had become a single entry Wolands by 1755).

Another name which describes the field’s shape is Picked Lease. ‘Picked’ (to rhyme with ‘wicked’) refers to a ‘peak’ or ‘pike’, a common description for a triangular piece of land.[15] Its whereabouts cannot be pinpointed with certainty although it must have been in the northern part of Rudloe. Thomas Goddard owned fields called Picked Mead and Picked Marsh on his Swindon estate; Edward Smith’s map, pasted into the field-book, shows that both were triangular plots.

Other field names are more prosaic. ‘Eighteen Acres’ should be self-explanatory; there are in fact two Rudloe fields called ‘eighteen acres’ in the 1838 tithe apportionment, but Thomas Goddard’s field of that name is clearly the one adjacent to Boxfields Tineing, and, again, enclosed from the open field, rather than the Eighteen Acres field just south of Hag Hill. ‘The Nine and Six Acres’ (which cannot be identified with any certainty), just under fifteen acres in the field-book terrier but not evident in 1722 or 1755, hints at the earlier amalgamation of two smaller fields.

Burnt House is presumably in the same general area as ‘China Wood or Burnt House Ground’ in the Tithe apportionment. It suggests an area of arable with evidence for burning; which in turn may indicate a site of former occupation. Coniger/Cunniger Wood is derived from Middle English Coninger, a rabbit warren. This may refer to a purpose built mound (sometimes referred to as a pillow-mound) constructed to provide a source of rabbit meat and fur, or may simply denote a wood with several rabbit burrows.

Upper and Lower Mankards, an area of 11 acres, correlates with two candidates of broadly similar extent in the Tithe apportionment; Manchards (no 54) at 12-1-5 and Manchard’s Mead (no 53), at 10-2-9. Thus the Mankards occupy twice as large an area in the Tithe apportionment as in the field-book. The 1755 survey refers to Great and Little Mankers, clearly the same fields as the Upper and Lower Mankards of the field-book, as extent of the area recorded is identical, whilst in 1722 there were two separate entries, naming the fields as Great Mancroft Water and Little Mancroft Water. The 1722 survey was subsequently annotated by Edward Lee ‘Lower mancroft Water now’. The Mancroft Water form of the field-name provides an additional clue; Mancroft/Meancroft field-names are often found on parish boundaries, where the sense is ‘land common to two communities’.[16] At this point the Bybrook valley is relatively wide and flat; the land here may often have been ‘water’ and in the medieval period the precise boundary here between Colerne and Box may have been difficult to delineate. Thus we appear to have a lower level area adjacent to the By Brook and a better-drained upper area on the slight slope along the southeast margin, the amalgamation having taken place between the 1722 and 1755 surveys, although the field-name may well be older than the surviving documentation.

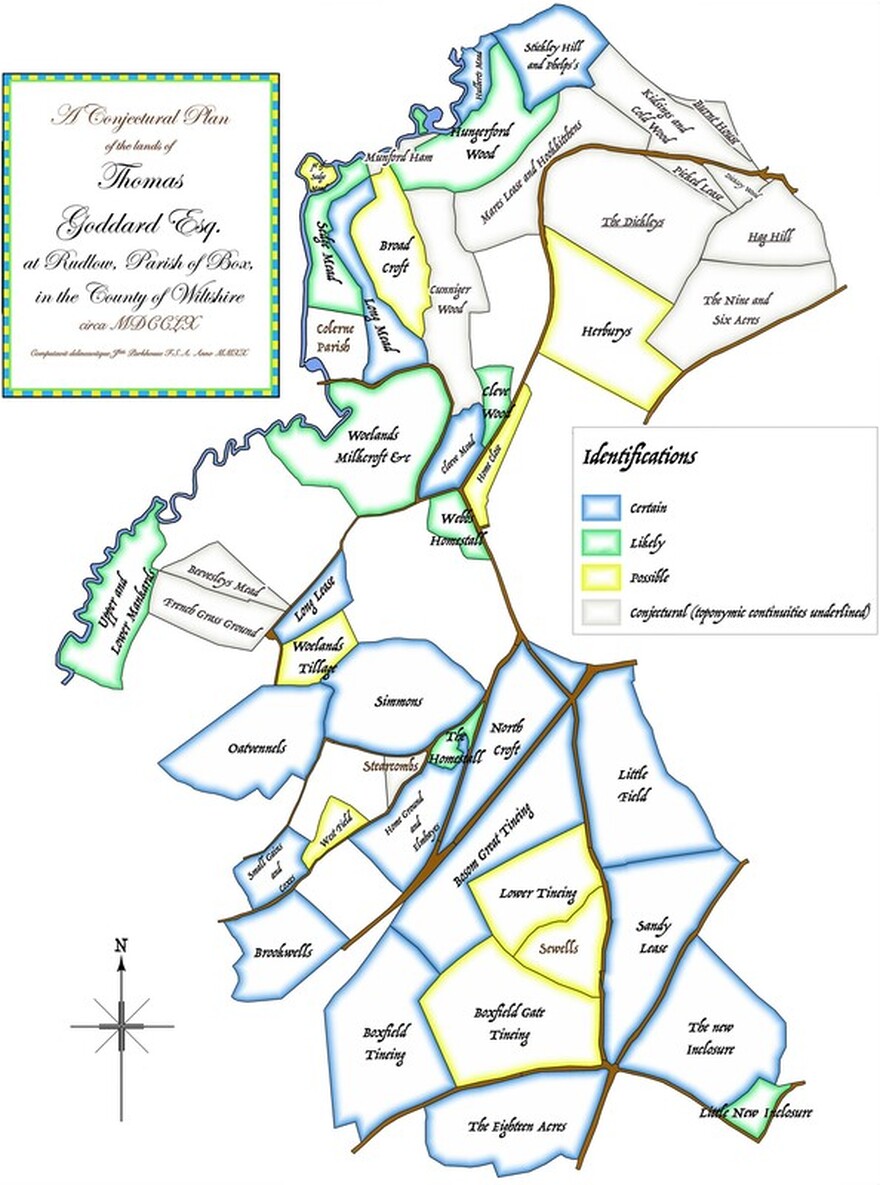

With these considerations in mind, we may attempt to reproduce the missing map. It should be emphasised that the reconstruction presented here is, to a greater or lesser extent, speculative. Some elements can be identified with greater confidence than others; although there is an element of subjectivity, four levels of confidence have been assigned to the identifications presented in our map.

Burnt House is presumably in the same general area as ‘China Wood or Burnt House Ground’ in the Tithe apportionment. It suggests an area of arable with evidence for burning; which in turn may indicate a site of former occupation. Coniger/Cunniger Wood is derived from Middle English Coninger, a rabbit warren. This may refer to a purpose built mound (sometimes referred to as a pillow-mound) constructed to provide a source of rabbit meat and fur, or may simply denote a wood with several rabbit burrows.

Upper and Lower Mankards, an area of 11 acres, correlates with two candidates of broadly similar extent in the Tithe apportionment; Manchards (no 54) at 12-1-5 and Manchard’s Mead (no 53), at 10-2-9. Thus the Mankards occupy twice as large an area in the Tithe apportionment as in the field-book. The 1755 survey refers to Great and Little Mankers, clearly the same fields as the Upper and Lower Mankards of the field-book, as extent of the area recorded is identical, whilst in 1722 there were two separate entries, naming the fields as Great Mancroft Water and Little Mancroft Water. The 1722 survey was subsequently annotated by Edward Lee ‘Lower mancroft Water now’. The Mancroft Water form of the field-name provides an additional clue; Mancroft/Meancroft field-names are often found on parish boundaries, where the sense is ‘land common to two communities’.[16] At this point the Bybrook valley is relatively wide and flat; the land here may often have been ‘water’ and in the medieval period the precise boundary here between Colerne and Box may have been difficult to delineate. Thus we appear to have a lower level area adjacent to the By Brook and a better-drained upper area on the slight slope along the southeast margin, the amalgamation having taken place between the 1722 and 1755 surveys, although the field-name may well be older than the surviving documentation.

With these considerations in mind, we may attempt to reproduce the missing map. It should be emphasised that the reconstruction presented here is, to a greater or lesser extent, speculative. Some elements can be identified with greater confidence than others; although there is an element of subjectivity, four levels of confidence have been assigned to the identifications presented in our map.

|

Certain: Close match of both toponyms (place names) and area between Goddard Fieldbook Terrier and Tithe Apportionment; in some instances discrepancies in size may be accounted for (for example the construction of the turnpike road);

Likely: Toponymic continuity, or roughly appropriate size, or appropriate position within terrier sequence relative to ‘certain’ identifications. Includes some identifications which would otherwise be certain where discrepancies in area imply boundary shifts which are not independently corroborated; Possible: As per ‘likely’, but identification more reliant on relationship to more confident identifications within terrier sequence; Conjectural: No evidence other than relative position within terrier sequence; in a few cases there is some toponymic continuity. |

It will be seen that the southern part of Thomas Goddard’s Rudloe estate may be reconstructed with greater confidence than the northern part. A significant proportion of this southern sector consists of what was once part of Box Field, one of the large open fields which had dominated the medieval landscape and which was still being cultivated in the traditional manner by the time of the early 17th century Allen survey. The fieldnames ‘New Inclosure’ and ‘Little New Enclosure’ are testament to the piecemeal enclosure of the open fields that had started before the 17th century and was probably complete, or nearly so, by Thomas Goddard’s time (in the case of his Swindon estate the process was less advanced, as he clearly owned strips of land that were situated within open fields). The four ‘tineing’ fieldnames south of the pre-turnpike road from Box towards Hartham and Corsham illustrate, as we have seen, the gradual fencing in of what had been open fields at the time of the Allen surveys. Fences could be moved more readily than walls or hedges, and within individual land-ownerships there may have been a degree of fluidity in the boundaries between lands recently enclosed. The area listed in the field-book as ‘Woelands, Milkcroft &c’ is, as noted above, another possible instance of areas being amalgamated, at least for the purposes of survey, into a single unit.

We may suspect that something similar also took place within the northern part of Thomas Goddard’s estate, but here we have no 17th century maps to guide us. The north-eastern sector is particularly problematic. However, the entry in the terrier described as ‘The Dickleys in one’ may indicate the lumping together for survey purposes of a number of small pieces of land fenced off from a previously open field. The extent of The Dickleys in One in the Field-book terrier is over twice as large as the Dicklease areas in either the 1722 or 1755 surveys. The entry in the 1755 survey refers to ‘Dickleaze and some of Richd Webbs’, which adds to the uncertainty. The approximate position of the Dickleys is likely to be indicated by a field called Duckleys in the tithe apportionment, which in turn is likely to be in a similar location to the meadow ‘called Dizleaze otherwise Dutlease’ referred to in the inquisition post mortem of Henry Long, dating to 1629,[17] which had been held by his mother Alice Long prior to her death in 1596.

“Hag Hill’ may also be a name associated with field enclosure, from Old English haga a fence or fenced enclosure, although haga also had the meaning haw (hawthorn berry).[18] The ‘hook’ element of ‘Hookkitchens’ may be from OE hoc, used in the sense of corner, or headland, but the name may well be related to Innox, from inhoc, an early partial enclosure of the open fields.[19] The Lease fieldnames in this area suggest the possibility of some areas alternating between pasture and arable. However, in this northern part there was clearly more in the way of woodland, possibly in a continuous strip along the summit of the northern end of the Rudloe ridge (Hungerford Wood, Cunniger Wood and Cleve Wood), with outliers a little way to the east (Cold Wood and Dickley Wood). By the 19th century this was largely arable except where woodland survived. Along the By Brook there was more in the way of meadow and pasture; as we have seen, the field identified as Sedge Mead, together with adjacent fields in Colerne parish, contains traces of what may have been a water meadow, although even if the identification is correct we cannot be sure whether it was still operational by the time the terrier was compiled.

We may suspect that something similar also took place within the northern part of Thomas Goddard’s estate, but here we have no 17th century maps to guide us. The north-eastern sector is particularly problematic. However, the entry in the terrier described as ‘The Dickleys in one’ may indicate the lumping together for survey purposes of a number of small pieces of land fenced off from a previously open field. The extent of The Dickleys in One in the Field-book terrier is over twice as large as the Dicklease areas in either the 1722 or 1755 surveys. The entry in the 1755 survey refers to ‘Dickleaze and some of Richd Webbs’, which adds to the uncertainty. The approximate position of the Dickleys is likely to be indicated by a field called Duckleys in the tithe apportionment, which in turn is likely to be in a similar location to the meadow ‘called Dizleaze otherwise Dutlease’ referred to in the inquisition post mortem of Henry Long, dating to 1629,[17] which had been held by his mother Alice Long prior to her death in 1596.

“Hag Hill’ may also be a name associated with field enclosure, from Old English haga a fence or fenced enclosure, although haga also had the meaning haw (hawthorn berry).[18] The ‘hook’ element of ‘Hookkitchens’ may be from OE hoc, used in the sense of corner, or headland, but the name may well be related to Innox, from inhoc, an early partial enclosure of the open fields.[19] The Lease fieldnames in this area suggest the possibility of some areas alternating between pasture and arable. However, in this northern part there was clearly more in the way of woodland, possibly in a continuous strip along the summit of the northern end of the Rudloe ridge (Hungerford Wood, Cunniger Wood and Cleve Wood), with outliers a little way to the east (Cold Wood and Dickley Wood). By the 19th century this was largely arable except where woodland survived. Along the By Brook there was more in the way of meadow and pasture; as we have seen, the field identified as Sedge Mead, together with adjacent fields in Colerne parish, contains traces of what may have been a water meadow, although even if the identification is correct we cannot be sure whether it was still operational by the time the terrier was compiled.

The enclosure of the common fields went hand in hand with development of a market in land. The extent of Goddard landholdings in Box parish seems to have fluctuated. Rudloe Manor, built by Thomas Goddard’s grandfather (also Thomas) had been sold at the end of the 17th century, and the same Thomas, whilst describing himself in his will of 1703 as Thomas Goddard of Rudlow, also owned land in ‘Wodswick’ (sic). The will records an intention to sell the Wadswick lands (along with lands elsewhere in North Wiltshire) in order to pay debts, with any remaining land passing to his son Ambrose.[20] Some of this land was purchased by William Jeffrey for the sum of £20/5s/-, including parts of Chapel Field, both within what may still have been open fields and areas which were enclosed by the time they were mapped by Abraham Allen in 1626.[21] The Jeffrey family also owned land in Rudlow, which may be identified as the area between the land parcels identified on our reconstructed map as ‘Upper and Lower Mankards, and ‘Woelands Milkcroft &c’; in 1838 this consisted of three units, named in the tithe apportionment as Jeffery’s Mead, Jeffery’s Wood and Jeffery’s Arable.

The Allen maps of Box show a fieldscape with a diverse mosaic of small strips of land within the remnants of the common fields, together with larger fields and closes; by the time of the tithe apportionment this pattern had coalesced into a number of distinct landholdings as owners consolidated their estates. Our reconstructed map of Rudloe shows an intermediate stage in this process of consolidation; the Goddards had assembled an estate that consisted of several large blocks of contiguous fields, but there were still gaps where other owners held land. The evidence from the survey documents suggests that in the late 1750s Thomas Goddard was buying up land.

The Goddard documents unfortunately give little direct indication of the use to which individual fields were being put, apart from a few later annotations in Edward Lee’s handwriting. The Tithe apportionment gives an overview of land-use in 1838 whilst deeds and wills of the 17th to 19th centuries refer to arable, pasture and meadow. Some general idea of agricultural regimes in northwest Wiltshire a generation or so after the Goddard occupancy of Rudloe is given by Thomas Davis in his report to the Board of Agriculture; he notes the improvements consequent upon enclosure ‘at no very remote period’ and the introduction of turnpike roads, but comments that the progress of enclosure had slowed.[22]

One product of Goddard’s estate is hinted at in one of the more interesting fieldnames: French Grass Ground. French Grass may refer to Onobrychis sativa or O. viciifolia, Sainfoin (derived from the French for ‘healthy hay’), a member of the bean family which was grown as a forage crop during the 17th – 19th centuries and into the 20th century, and which grows well on thin soils and limestone rich downlands. It was a high quality hay, fed to heavy horses whilst the aftermath grazing was used for fattening lambs, and in some Cotswold tenancy agreements it was stipulated that sainfoin should be grown regularly.[23] Davis notes that sainfoin was frequently sown in North Wiltshire, although often in soils that were too cold and damp for it to prosper,[24] and a 1704 Glebe Terrier for Box records that the vicar should have ‘The tenth cock of all Hay growing in the Said Parish: and of ffrench-grasse, called St Jane [sic], or of the seed of it’.[25] Alternatively, however, French Grass may refer to young shoots of Ornithogalum pyrenaicum, Spiked Star-of-Bethlehem or Bath Asparagus, where grass is an abbreviation of ‘Sparrow Grass’ the young shoots being used as a substitute for asparagus and sold in the market at Bath. This usage was recorded from Somerset in the 19th century;[26] it is described as a scarce but locally abundant native plant in Southern England, growing in woods, hedgerows and grassy verges, mostly on clayey soils overlaying limestones or gravels.[27] Both types of French Grass would have been suited to Rudloe soil, are historically attested within the general locality, and still occur wild in the parish.[28] Nevertheless, whilst the field-name may refer to either plant, it is more likely that a field-name would reflect what was grown within the field rather than along its hedged margin; in this way the reference is more likely to be to sainfoin than to Bath Asparagus.[29]

The Allen maps of Box show a fieldscape with a diverse mosaic of small strips of land within the remnants of the common fields, together with larger fields and closes; by the time of the tithe apportionment this pattern had coalesced into a number of distinct landholdings as owners consolidated their estates. Our reconstructed map of Rudloe shows an intermediate stage in this process of consolidation; the Goddards had assembled an estate that consisted of several large blocks of contiguous fields, but there were still gaps where other owners held land. The evidence from the survey documents suggests that in the late 1750s Thomas Goddard was buying up land.

The Goddard documents unfortunately give little direct indication of the use to which individual fields were being put, apart from a few later annotations in Edward Lee’s handwriting. The Tithe apportionment gives an overview of land-use in 1838 whilst deeds and wills of the 17th to 19th centuries refer to arable, pasture and meadow. Some general idea of agricultural regimes in northwest Wiltshire a generation or so after the Goddard occupancy of Rudloe is given by Thomas Davis in his report to the Board of Agriculture; he notes the improvements consequent upon enclosure ‘at no very remote period’ and the introduction of turnpike roads, but comments that the progress of enclosure had slowed.[22]

One product of Goddard’s estate is hinted at in one of the more interesting fieldnames: French Grass Ground. French Grass may refer to Onobrychis sativa or O. viciifolia, Sainfoin (derived from the French for ‘healthy hay’), a member of the bean family which was grown as a forage crop during the 17th – 19th centuries and into the 20th century, and which grows well on thin soils and limestone rich downlands. It was a high quality hay, fed to heavy horses whilst the aftermath grazing was used for fattening lambs, and in some Cotswold tenancy agreements it was stipulated that sainfoin should be grown regularly.[23] Davis notes that sainfoin was frequently sown in North Wiltshire, although often in soils that were too cold and damp for it to prosper,[24] and a 1704 Glebe Terrier for Box records that the vicar should have ‘The tenth cock of all Hay growing in the Said Parish: and of ffrench-grasse, called St Jane [sic], or of the seed of it’.[25] Alternatively, however, French Grass may refer to young shoots of Ornithogalum pyrenaicum, Spiked Star-of-Bethlehem or Bath Asparagus, where grass is an abbreviation of ‘Sparrow Grass’ the young shoots being used as a substitute for asparagus and sold in the market at Bath. This usage was recorded from Somerset in the 19th century;[26] it is described as a scarce but locally abundant native plant in Southern England, growing in woods, hedgerows and grassy verges, mostly on clayey soils overlaying limestones or gravels.[27] Both types of French Grass would have been suited to Rudloe soil, are historically attested within the general locality, and still occur wild in the parish.[28] Nevertheless, whilst the field-name may refer to either plant, it is more likely that a field-name would reflect what was grown within the field rather than along its hedged margin; in this way the reference is more likely to be to sainfoin than to Bath Asparagus.[29]

Explaining the ‘with mounds’ measurements

In the first pat of this account, it was suggested that the series of measurements in the field-book described as ‘with mounds’ might represent the surveyor’s attempt to reconcile measurement of a three dimensional surface with a two dimensional plan representation, either because the land contained remnants of ridge and furrow (which could be described as ‘mounds’) or, more likely, that there was a natural slope. This hypothesis was tested against the reconstructed plan of Thomas Goddard’s estate at Rudloe. Comparison of the two sets of measurements for each field – with mounds and without mounds – allowed calculation of the difference between the two as a notional slope value, in other words the number of degrees of slope which would be represented by the excess of the with area over the without area.[30] This assumes that the slope is consistent and in a single plane across a square field, which is clearly never the case. It also assumes that the 18th century surveyor was able to measure both values accurately, which is also highly problematic. Nevertheless, the calculation should in theory provide a very crude basis for determining whether a field was relatively flat or on a slope.

Where field identifications were ‘certain’ or ‘likely’, an attempt was made to check whether the slope value derived from the Goddard measurements was consistent with the present topography. The height detail provided by the contours on Ordnance Survey maps is of insufficient resolution to check slope gradients; however, ground elevation data from lidar is of excellent quality, allowing extraction of spot height values to within a few centimetres accuracy for any point. At the time these calculations were initially undertaken, in the spring of 2020, available lidar data only covered about half of the study area, but enough to attempt to make the comparison. Spot height values were extracted from the raw lidar data and slope values calculated along the straight line chosen to show maximum height variation across each field.[31] The degree of correlation between the two sets of values was variable. Some fields showed a reasonably good fit between the slopes calculated by the two methods, but others showed a discrepancy significantly greater than one would expect, even if the ground surface had been far more uneven, for whatever reason, in the 18th century and it seemed likely that the relationship between the two sets of measurements was more complex than was allowed for by the original hypothesis. The eventual release of more up to date Lidar data by the Environment Agency later in 2020 prompted the author to revisit the issue. The most recent data was captured in the winter of 2018/19 and covers the entire parish of Box. Once actual ground slopes across the entire study area could be calculated it became apparent that no direct relationship existed between ground slope and the difference between the two sets of measurements in the field-book.

However, although the earlier hypothesis could be discarded, the newly discovered documents of 1722 and 1755 provide a far more plausible explanation for the meaning of ‘with mounds’. It can be seen that in a majority of instances the ‘with mounds’ measurement of the field-book equated to the sum of the ‘Tillage and pasture’ and the ‘Bounds and Brakes’ measurements of the 1722 survey, either precisely or with a variation of a single pole. One may therefore suggest that the description ‘with mounds’ is a mistake; it should have been ‘with bounds’.

As the handwriting in all the documents is relatively easy to read one may ask how a transcription error could have occurred. Whilst ‘mounds’ and ‘bounds’ are readily distinguishable when written, the words are near-homophones, so it would be entirely possible to imagine one word being mis-heard as the other. We may therefore surmise that dictation was involved in the compilation of the Rudloe pages of the field-book, and possibly even that the person writing in the field-book - perhaps Thomas Goddard himself - was hard of hearing!

In theory there will be a relationship between the measurements for ‘Bounds and Brakes’ recorded in 1722 and the length of the perimeter around each field. However, the thickness of hedgerows and boundaries will have varied significantly; newly enclosed areas may have been surrounded by fences rather than hedges, and some roads and tracks may not have been hedged. Nor is there any way of knowing the extent of the brakes (here used in the sense of a thicket, or an area of dense undergrowth, shrubs or bracken, from the Old English bracu, bracken or fern) amongst the Rudloe fields. There are just too many variables to be able to demonstrate any mathematical correlation between the historic measurements and the current lengths of the field perimeters.

In the first pat of this account, it was suggested that the series of measurements in the field-book described as ‘with mounds’ might represent the surveyor’s attempt to reconcile measurement of a three dimensional surface with a two dimensional plan representation, either because the land contained remnants of ridge and furrow (which could be described as ‘mounds’) or, more likely, that there was a natural slope. This hypothesis was tested against the reconstructed plan of Thomas Goddard’s estate at Rudloe. Comparison of the two sets of measurements for each field – with mounds and without mounds – allowed calculation of the difference between the two as a notional slope value, in other words the number of degrees of slope which would be represented by the excess of the with area over the without area.[30] This assumes that the slope is consistent and in a single plane across a square field, which is clearly never the case. It also assumes that the 18th century surveyor was able to measure both values accurately, which is also highly problematic. Nevertheless, the calculation should in theory provide a very crude basis for determining whether a field was relatively flat or on a slope.

Where field identifications were ‘certain’ or ‘likely’, an attempt was made to check whether the slope value derived from the Goddard measurements was consistent with the present topography. The height detail provided by the contours on Ordnance Survey maps is of insufficient resolution to check slope gradients; however, ground elevation data from lidar is of excellent quality, allowing extraction of spot height values to within a few centimetres accuracy for any point. At the time these calculations were initially undertaken, in the spring of 2020, available lidar data only covered about half of the study area, but enough to attempt to make the comparison. Spot height values were extracted from the raw lidar data and slope values calculated along the straight line chosen to show maximum height variation across each field.[31] The degree of correlation between the two sets of values was variable. Some fields showed a reasonably good fit between the slopes calculated by the two methods, but others showed a discrepancy significantly greater than one would expect, even if the ground surface had been far more uneven, for whatever reason, in the 18th century and it seemed likely that the relationship between the two sets of measurements was more complex than was allowed for by the original hypothesis. The eventual release of more up to date Lidar data by the Environment Agency later in 2020 prompted the author to revisit the issue. The most recent data was captured in the winter of 2018/19 and covers the entire parish of Box. Once actual ground slopes across the entire study area could be calculated it became apparent that no direct relationship existed between ground slope and the difference between the two sets of measurements in the field-book.

However, although the earlier hypothesis could be discarded, the newly discovered documents of 1722 and 1755 provide a far more plausible explanation for the meaning of ‘with mounds’. It can be seen that in a majority of instances the ‘with mounds’ measurement of the field-book equated to the sum of the ‘Tillage and pasture’ and the ‘Bounds and Brakes’ measurements of the 1722 survey, either precisely or with a variation of a single pole. One may therefore suggest that the description ‘with mounds’ is a mistake; it should have been ‘with bounds’.

As the handwriting in all the documents is relatively easy to read one may ask how a transcription error could have occurred. Whilst ‘mounds’ and ‘bounds’ are readily distinguishable when written, the words are near-homophones, so it would be entirely possible to imagine one word being mis-heard as the other. We may therefore surmise that dictation was involved in the compilation of the Rudloe pages of the field-book, and possibly even that the person writing in the field-book - perhaps Thomas Goddard himself - was hard of hearing!

In theory there will be a relationship between the measurements for ‘Bounds and Brakes’ recorded in 1722 and the length of the perimeter around each field. However, the thickness of hedgerows and boundaries will have varied significantly; newly enclosed areas may have been surrounded by fences rather than hedges, and some roads and tracks may not have been hedged. Nor is there any way of knowing the extent of the brakes (here used in the sense of a thicket, or an area of dense undergrowth, shrubs or bracken, from the Old English bracu, bracken or fern) amongst the Rudloe fields. There are just too many variables to be able to demonstrate any mathematical correlation between the historic measurements and the current lengths of the field perimeters.

Conclusions

The sometime doyen of landscape historians, W.G. Hoskins, warned that ‘the minute study of local topography can become a bottomless morass… one is overwhelmed in loving but futile detail’.[32] Hoskins, however, might very well have revised his observation had he been able to benefit from the opportunities afforded by modern technology, and particularly Geographical Information Systems (GIS) to capture, store, and analyse spatial data. Rather than being merely ‘futile detail’, the Goddard documents provided a means of approaching a less-studied part of Box parish through the integration of landscape archaeology and documentary analysis. The discovery that the terrier in the field-book had almost certainly been accompanied by a map provided the impetus to try to analyse a small area of the local landscape. The emergence of the 1722 and 1755 surveys was a purely fortuitous bonus, the collection of three surveys concerning more or less the same land indicating how such documents were used for estate management and recording. The Goddard terriers provide a snapshot of a part of Box during a period of transition, some considerable distance along the path from a feudal mosaic of small land-holdings and tenancies, towards a fully developed capitalist farming model with its thriving and dynamic land market.

Inevitably a study of this nature will raise as many questions as it provides answers. It should be clear that some of the identifications and conclusions put forward here are tentative, and the resulting map should not be read uncritically; it is even possible that once again deeds or other documents will emerge which may shed further light on the issue. History is never simply done and dusted.

The sometime doyen of landscape historians, W.G. Hoskins, warned that ‘the minute study of local topography can become a bottomless morass… one is overwhelmed in loving but futile detail’.[32] Hoskins, however, might very well have revised his observation had he been able to benefit from the opportunities afforded by modern technology, and particularly Geographical Information Systems (GIS) to capture, store, and analyse spatial data. Rather than being merely ‘futile detail’, the Goddard documents provided a means of approaching a less-studied part of Box parish through the integration of landscape archaeology and documentary analysis. The discovery that the terrier in the field-book had almost certainly been accompanied by a map provided the impetus to try to analyse a small area of the local landscape. The emergence of the 1722 and 1755 surveys was a purely fortuitous bonus, the collection of three surveys concerning more or less the same land indicating how such documents were used for estate management and recording. The Goddard terriers provide a snapshot of a part of Box during a period of transition, some considerable distance along the path from a feudal mosaic of small land-holdings and tenancies, towards a fully developed capitalist farming model with its thriving and dynamic land market.

Inevitably a study of this nature will raise as many questions as it provides answers. It should be clear that some of the identifications and conclusions put forward here are tentative, and the resulting map should not be read uncritically; it is even possible that once again deeds or other documents will emerge which may shed further light on the issue. History is never simply done and dusted.

Acknowledgements

I owe a great debt to the owner of three of the documents discussed here for permission to use the material in their care and for providing photographs. It is always the historian’s wish that further documentation will be found to support or refute his or her hypotheses, but rare that serendipity provides it even before the hypotheses are published; we are fortunate that the individual concerned has been so willing to help. I am grateful to Alan Payne for his encouragement, his patience as various updated drafts were submitted, and for sharing his own notes on the Rudloe Goddards, and to Carol Payne for the photographs of the Goddard monuments in St Thomas’s church which accompanied the previous article. Tom Sunley of the Wiltshire Historic Environment Record kindly gave permission for use of data from the Wiltshire and Swindon Historic Landscape Characterisation. Staff at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre have been unfailingly helpful in providing access to documents and for permission to reproduce extracts from documents in their care; it is a privilege to be able to access the raw materials of history with such ease. May all those acknowledged forgive me for the imperfections herein.

I owe a great debt to the owner of three of the documents discussed here for permission to use the material in their care and for providing photographs. It is always the historian’s wish that further documentation will be found to support or refute his or her hypotheses, but rare that serendipity provides it even before the hypotheses are published; we are fortunate that the individual concerned has been so willing to help. I am grateful to Alan Payne for his encouragement, his patience as various updated drafts were submitted, and for sharing his own notes on the Rudloe Goddards, and to Carol Payne for the photographs of the Goddard monuments in St Thomas’s church which accompanied the previous article. Tom Sunley of the Wiltshire Historic Environment Record kindly gave permission for use of data from the Wiltshire and Swindon Historic Landscape Characterisation. Staff at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre have been unfailingly helpful in providing access to documents and for permission to reproduce extracts from documents in their care; it is a privilege to be able to access the raw materials of history with such ease. May all those acknowledged forgive me for the imperfections herein.

References

[1] See the first of the maps accompanying the previous article (http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/rudloe-history.html)

[2]Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre 894/4. A Richard Garven from Corshamside (Neston) died 13 March 1739; Society of Friends (Quaker) burial records ref RG6/1014. I am grateful to Alan Payne for this identification.

[3] Wiltshire and Swindon Record Centre: ref 1265/3

[4] J Parkhouse and A Payne, 2019, ‘Tithe Apportionment, 1836-40’. Box People and Places issue 26:

http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/tithe-apportionment.html .

[5] In fact several groupings of land parcels are cited in the same order in all three documents, as the concordance shows.

[6] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1022810 (better photograph than mine!).

[7] The Webbs had owned land in Rudloe since at least the 17th century as well as at Ditteridge (D. Rawlings, 2016 The Webb Family in Stuart and Georgian Times’ Box People and Places 11 http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/webb-family-at-coles-farm.html ). Amongst a collection of deeds and papers of the Webb family at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre (ref 2822/2) are a draft settlement of some lands at Rudloe by Peter Webb on his son William in 1668, a deed of sale of two closes by Susanna Webb to her son Samuel in 1676/7, and a marriage settlement between Peter Webb (?grandson of the first Peter Webb) and Mary Harrison in 1717, all of which refer to fieldnames, and the first and last giving acreages. However, only one field, named Broadcroft, has the same acreage in 1717 as it did in 1668, and none of the other field names matches those owned in Rudloe by their descendant Edward Webb in the Tithe apportionment, so there is no means of identifying them. Broadcroft, however, was amongst the fields in the Goddard terrier; assuming that it is the same piece of land, it must have been purchased by the Goddards from the Webbs between 1717 and 1722. The Webb documents describe areas to the nearest acre: Broadcroft was 12 acres, but 10-0-16 in the Goddard field-book and 9-2-31 in the 1722 survey.

[8] Unfortunately the constraints of the current pandemic have prevented the author from accessing either of these collections.

[9] A meadow called Sedgeham was amongst the lands at Rudloe owned by Alice Long at her death in 1596. GS Fry and EA Fry (eds), 1901, Abstracts of Wiltshire Inquisitiones Post Mortem, returned into the Court of Chancery in the reign of King Charles the First (London, British Record Society), p86

[10] This is very likely the field called Brackwells which was another possession of Alice Long. GS Fry and EA Fry (eds), loc. cit.

[11] Bath Journal, December 1761, quoted in Phillips D , 1983, The Great Road to Bath (Countryside Books, Newbury) , 35. See also http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/the-new-road-1761.html .

[12] IH Adams, 1976, Agrarian landscape terms: a glossary for historical geography (Institute of British Geographers Special Publication 9); J Field , 1993, A history of English field-names, pp 24-25, 93.

[13] Field, loc. cit., p108.

[14] Field, loc. cit., p136.

[15] Field, loc. cit., p134.

[16] P.Cavill, 2018 A new Dictionary of English Field-names (Nottingham, English Place-name Society), p.268

[17] GS Fry and EA Fry, loc. cit., p86

[18] E. Ekwall, 1960, Concise Oxford Dctionary of English Place-names (4th edn) (Clarendon, Oxford), p248

[19] ‘Innox’ is still retained in the White Ennox Lane (which must take its name from the field shown as Whit Inx on the 1630 Allen Map (see map extract above); Allen also shows an Innox between Hatt Farm and Kingsdown). The name survives in a variety of forms. JEB Gover, A Mawer and FM Stenton (1970, The Place-names of Wiltshire English Place-name Society Vol 16, Cambridge University Press, pp.134 and 438) note the use of inhoc, inhoke in the 13th and 14th centuries to describe land temporarily enclosed from the fallow and put under cultivation. It is most common in Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire and Somerset, generally used in the plural. “Its history is obscure. It has been associated with OE hoc, ‘hook’, used possibly in the sense ‘corner, angle,’ but in these circumstances the in does not seem to have much meaning. More probably inhok is what results from a process of ‘in-hooking’, i.e. hooking or bringing into cultivation, the verb inhokare being on record from medieval documents”. It thus signifies an early partial enclosure. Other Wiltshire examples include Le Hinhoc, 13th-century in Lacock, Muchele Ynhok 1397, later Innex in Colerne, Hinnex (early C17th) in Corsham, Northynnoke 1428, later Enox Piece, in Kington St Michael, and Le Inhoke, 1495, in Zeals.

[20] RWK Goddard, 1910, Goddard Wills p.43.

[21] P and C Ward, 2016 ‘William Brown: Rise of Yeoman Farmer’ Box People and Places Issue 14 http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/william-jeffery-brown.html ; this article notes that William Jeffery ‘the elder’ who died in 1716 had purchased land in Rudloe from Mary Simpsion. The 1727 will of his eldest son, also called William, refers to forty acres of Jeffery’s land lying against Goddard’s field containing about four acres (Wiltshire and Swindon Record Centre: ref P3/1J/243), although this is more likely to have been in the Chapel Field near Wadswick rather than at Rudloe.

[22] T Davis, 1794, revised 1811, General View of the Agriculture of Wiltshire: Drawn up and published by order of the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement, pp174-181.

[23] Although a native plant, formerly known as Cock’s-head, the cultivated form seems to have been a 17th century introduction (D Grose, 1957, The Flora of Wiltshire (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Devizes), p206). See also https://www.cotswoldseeds.com/species/55/sainfoin .

[24] T Davis, General View, (note 22 above), p181.

[25] Download at http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/tithe-apportionment.html

[26] J Britten and R Holland, 1886, A Dictionary of English Plant names, (Trübner & Co, London), p193. (https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofengl00brit/page/192/mode/2up ).

[27] DJ Hill and B Price, 2000, Ornithogalum pyrenaicum L. Journal of Ecology 88, 354-65. (https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00446.x ); D Green, 1993, ‘Ornithogalum pyrenaicum L. Spiked Star-of-Bethlehem or Bath Asparagus’, in B Gillam (ed) The Wiltshire Flora (Pisces Publications, Newbury), pp 99-100; distribution map in Gillam (ed) loc. cit., p352, showing a clear concentration in the Box/ Bradford-on-Avon area.

[28] Data from Wiltshire and Swindon Biological Records Centre.

[29] In 1838 a field north of Alcombe, overlooking the Lid Brook, was called French Grass Ground, but it cannot be the one described in Goddard’s terrier.

[30] Slope is derived from the inverse cosine of the square root of the area without mounds divided by the square root of the area with mounds, divided by two: ⍬= Cos-1(square root without / square root with)/2.

[31] Slope in degrees derived from ⍬=Tan-1(h/d) where h=difference in height between highest and lowest point and d = straight line distance between the two points.

[32] WG Hoskins, 1959 ‘Review’ [ of MW Beresford, 1957, History on the Ground], Economic History Review 2nd series,11, p.160.

[1] See the first of the maps accompanying the previous article (http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/rudloe-history.html)

[2]Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre 894/4. A Richard Garven from Corshamside (Neston) died 13 March 1739; Society of Friends (Quaker) burial records ref RG6/1014. I am grateful to Alan Payne for this identification.

[3] Wiltshire and Swindon Record Centre: ref 1265/3

[4] J Parkhouse and A Payne, 2019, ‘Tithe Apportionment, 1836-40’. Box People and Places issue 26:

http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/tithe-apportionment.html .

[5] In fact several groupings of land parcels are cited in the same order in all three documents, as the concordance shows.

[6] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1022810 (better photograph than mine!).

[7] The Webbs had owned land in Rudloe since at least the 17th century as well as at Ditteridge (D. Rawlings, 2016 The Webb Family in Stuart and Georgian Times’ Box People and Places 11 http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/webb-family-at-coles-farm.html ). Amongst a collection of deeds and papers of the Webb family at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre (ref 2822/2) are a draft settlement of some lands at Rudloe by Peter Webb on his son William in 1668, a deed of sale of two closes by Susanna Webb to her son Samuel in 1676/7, and a marriage settlement between Peter Webb (?grandson of the first Peter Webb) and Mary Harrison in 1717, all of which refer to fieldnames, and the first and last giving acreages. However, only one field, named Broadcroft, has the same acreage in 1717 as it did in 1668, and none of the other field names matches those owned in Rudloe by their descendant Edward Webb in the Tithe apportionment, so there is no means of identifying them. Broadcroft, however, was amongst the fields in the Goddard terrier; assuming that it is the same piece of land, it must have been purchased by the Goddards from the Webbs between 1717 and 1722. The Webb documents describe areas to the nearest acre: Broadcroft was 12 acres, but 10-0-16 in the Goddard field-book and 9-2-31 in the 1722 survey.

[8] Unfortunately the constraints of the current pandemic have prevented the author from accessing either of these collections.