Thomas Goddard’s Terrier of Rudloe

Text and illustrations Jonathan Parkhouse (unless stated otherwise) June 2020

Text and illustrations Jonathan Parkhouse (unless stated otherwise) June 2020

This is part 1 of Jonathan's research into the land held by the Goddard family in Rudloe. In this article he focuses on the family of Thomas Goddard and the records they kept of their estates.

The Goddard family at Rudloe

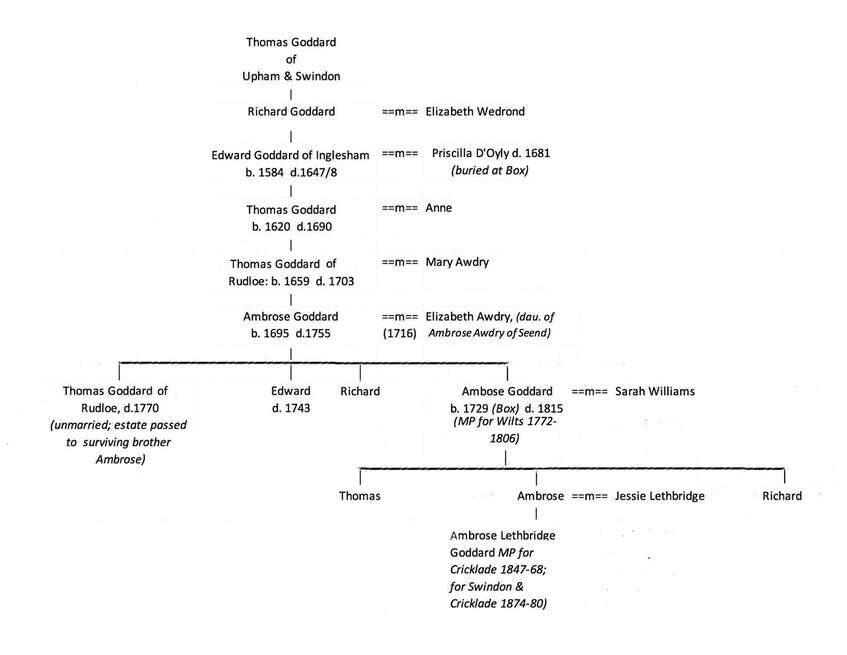

The Goddards were an extensive family, owning land in several places in Wiltshire and elsewhere. In 1231 a Walter Godardville was appointed castellan of Devizes by Henry III, and is presumably the individual referred to in an inquisition post mortem of 1249-50 who held land at Chippenham (Sheldon Manor) and Chyverel (Cherhill); he died without a male heir and is no longer thought to be the ancestor of the Wiltshire Goddards.[1] Confusingly, there is another thirteenth-century Walter who died in 1273; his son John who lived at Poulton near Marlborough appears to be the ancestor of the Goddards who owned land at Rudloe.[2] The early genealogy of the Goddard family is complex; the family tree presented here is only concerned with the Goddards associated with Rudloe and their immediate ancestors and descendants. A different branch of the family resided nearby at Hartham.

The Goddards were an extensive family, owning land in several places in Wiltshire and elsewhere. In 1231 a Walter Godardville was appointed castellan of Devizes by Henry III, and is presumably the individual referred to in an inquisition post mortem of 1249-50 who held land at Chippenham (Sheldon Manor) and Chyverel (Cherhill); he died without a male heir and is no longer thought to be the ancestor of the Wiltshire Goddards.[1] Confusingly, there is another thirteenth-century Walter who died in 1273; his son John who lived at Poulton near Marlborough appears to be the ancestor of the Goddards who owned land at Rudloe.[2] The early genealogy of the Goddard family is complex; the family tree presented here is only concerned with the Goddards associated with Rudloe and their immediate ancestors and descendants. A different branch of the family resided nearby at Hartham.

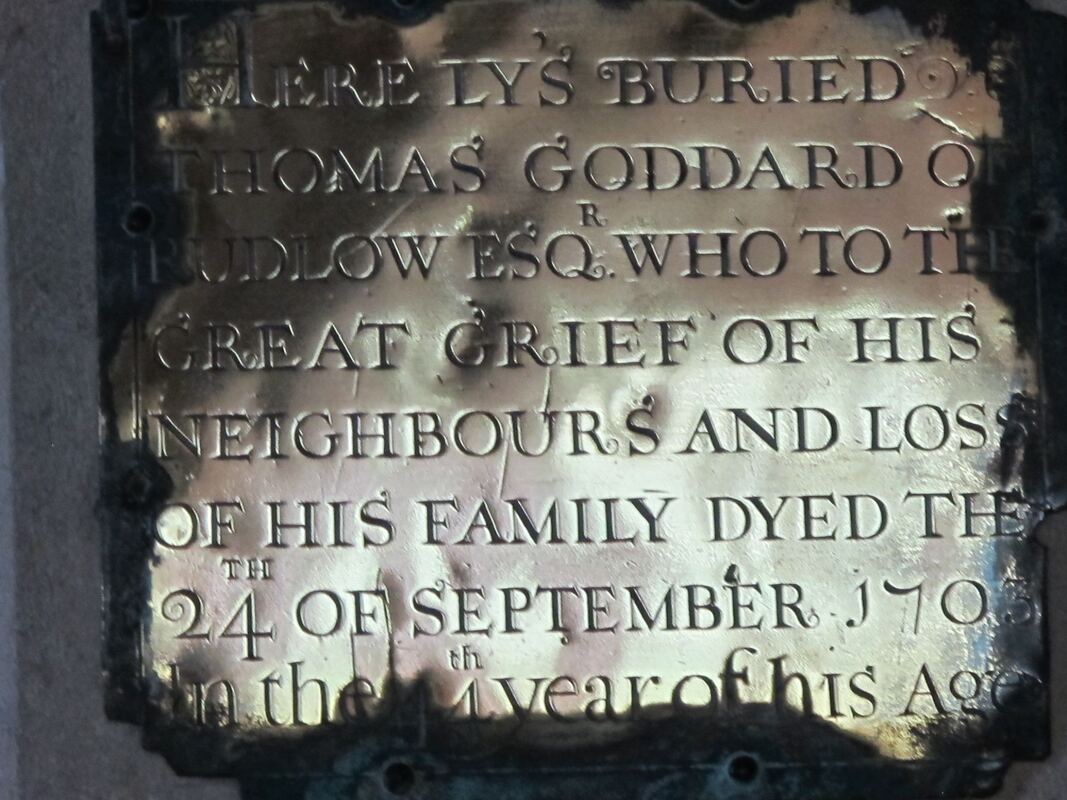

The earliest Goddard for whom we can demonstrate a Box connection is Priscilla, wife of Edward Goddard of Inglesham. She was born in 1594 and died and was buried in Box in 1681. Her son Thomas purchased Rudloe Manor from one Richard Kent, who had purchased it from the Hungerford family; it is likely that he brought his aged mother to live with him at Rudloe. Thomas is alleged to have built the present house in 1685 (since the building incorporates late 15th century elements this might better be described as a substantial rebuilding), but the ownership of the house passed shortly to Jacob Selfe of Melksham who died in 1702, and then into the Methuen family.[3] Thomas died in 1690, and the Rudloe estate passed to his son (also Thomas, died 1703), then to Ambrose (who in 1736 was one of only eleven individuals in Box qualified as freeholders to serve as jurors),[4] and then to another Thomas. This third Thomas, whose field-book is the principal subject of this note, did not marry, and when he died in 1770 the estate passed to his brother Ambrose, who was born in Box in 1729 and died in 1815, having served as MP for Wiltshire 1772-1806. Ambrose also inherited land elsewhere in Wiltshire from a cousin, Pleydell Goddard.[5] In Thomas’s will he refers to himself as of Swindon, rather than of Rudloe,[6] and the Goddards evidently became absentee landlords during the 18th century.[7]

Rudloe Manor, allegedly built (or, more probably, substantially rebuilt) by Thomas Goddard senior in 1685. This is the only building in Box to feature on the Heritage at Risk register maintained by Historic England, and it is highly regrettable that such a fine building has been allowed to fall into disrepair. (Photo courtesy Carol Payne)

Thomas Goddard’s Field-book

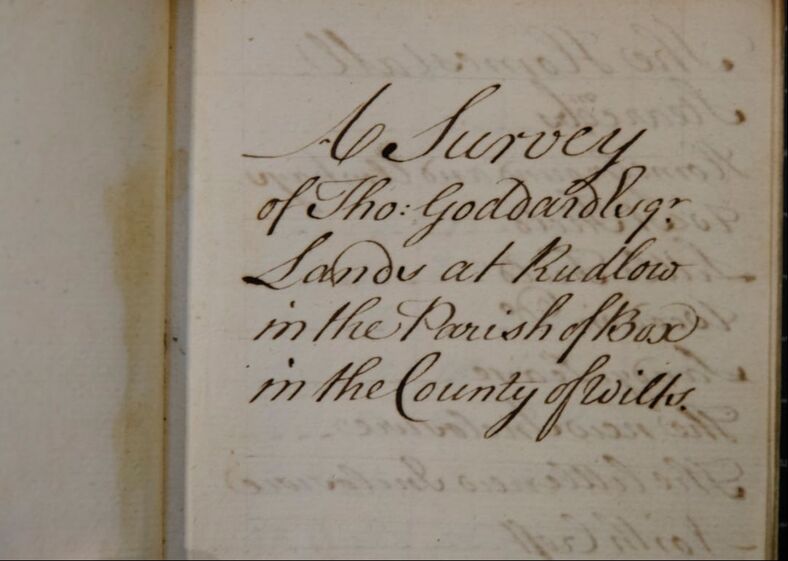

Amongst the documents held by the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre is the field-book used by Thomas Goddard, and later by his brother Ambrose, to record their estates, in a series of terriers (written surveys) of their land holdings described on a field by field basis.[8]

The field-book is a small bound notebook 3¾” x 6” (9.6 x 15.1 cm). Only the pages in the first part (roughly half) of the book have been used. The initial section, which is the most detailed, consists of surveys of parts of the manor of Swindon, surveyed in July 1763 by Edward Smith of Shrivenham, Berks, and accompanied by two small coloured maps pasted into the book. Like many landowners, Goddard used a professional surveyor to measure his lands; and Edward Smith is known to have undertaken surveys elsewhere.[9] None of the other terriers is attributed to a particular surveyor, so it is not known whether Edward Smith was involved other than at Swindon. Then follow brief descriptions (without maps) of lands held in the unenclosed fields at Swindon, measured in acres and roods and identified by occupier. Most fields are relatively small – between 2 roods and 2 acres, and Thomas Goddard himself is listed as the occupier of a number of the strips. Next comes a terrier of Draymead (part of the Swindon estate), which is followed by a note which sheds light on the techniques of 18th century surveyors:

Draymead is measured up the first Carriage with the Long pole of 14 foot [illegible] inches and 3 quarters (deleted in original), the other pole 14 foot 5 Inches and Three quarters begin measuring at Notford Hedge the first Straight Carriage Two poles to an acre.

Although the meaning is not entirely clear, the passage demonstrates that the survey equipment then in use was not necessarily calibrated to a precise standard. The 17th and 18th centuries saw the development of surveying instruments and methodology, along with various treatises which took account of trigonometry and logarithms for calculation. By the 1720s theodolites were being produced by makers such as Jonathan Sisson which are recognisable as ancestors of those still in use (at least until the introduction of the electronic measuring equipment of the present century), with vernier scales and bubble levels, and the accuracy of this apparatus gradually improved.[10] Plane tables were also widely used. However, such sophisticated instruments would be more commonly used by those engaged in the production of county and national maps; the ordinary estate surveyor seems to have been reliant on more traditional means of measurement using a surveyor’s chain (invented in its present form by Edmund Gunther in 1620) and, as here, surveying poles. The chain was 22 yards long, and divided into 100 links; however the unit of linear measurement most frequently encountered in written surveys is the rod, pole or perch. In 18th century Wiltshire the length of a pole could be 15 feet, 16½ feet or 18 feet. The 16½ foot pole, of which there were four to the chain, was that most commonly used and became the standard length, but the eighteen foot pole was used for measuring woodland in many parts of Wiltshire.[11] The measuring poles described in Goddard’s field-book are thus not a standard length, and although the exact length of the first pole is indecipherable one may infer that two poles of slightly different lengths were apparently being used at Goddard’s Swindon estates. There must therefore be a degree of caution in using the measurements in Goddard’s field book.

Amongst the documents held by the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre is the field-book used by Thomas Goddard, and later by his brother Ambrose, to record their estates, in a series of terriers (written surveys) of their land holdings described on a field by field basis.[8]

The field-book is a small bound notebook 3¾” x 6” (9.6 x 15.1 cm). Only the pages in the first part (roughly half) of the book have been used. The initial section, which is the most detailed, consists of surveys of parts of the manor of Swindon, surveyed in July 1763 by Edward Smith of Shrivenham, Berks, and accompanied by two small coloured maps pasted into the book. Like many landowners, Goddard used a professional surveyor to measure his lands; and Edward Smith is known to have undertaken surveys elsewhere.[9] None of the other terriers is attributed to a particular surveyor, so it is not known whether Edward Smith was involved other than at Swindon. Then follow brief descriptions (without maps) of lands held in the unenclosed fields at Swindon, measured in acres and roods and identified by occupier. Most fields are relatively small – between 2 roods and 2 acres, and Thomas Goddard himself is listed as the occupier of a number of the strips. Next comes a terrier of Draymead (part of the Swindon estate), which is followed by a note which sheds light on the techniques of 18th century surveyors:

Draymead is measured up the first Carriage with the Long pole of 14 foot [illegible] inches and 3 quarters (deleted in original), the other pole 14 foot 5 Inches and Three quarters begin measuring at Notford Hedge the first Straight Carriage Two poles to an acre.

Although the meaning is not entirely clear, the passage demonstrates that the survey equipment then in use was not necessarily calibrated to a precise standard. The 17th and 18th centuries saw the development of surveying instruments and methodology, along with various treatises which took account of trigonometry and logarithms for calculation. By the 1720s theodolites were being produced by makers such as Jonathan Sisson which are recognisable as ancestors of those still in use (at least until the introduction of the electronic measuring equipment of the present century), with vernier scales and bubble levels, and the accuracy of this apparatus gradually improved.[10] Plane tables were also widely used. However, such sophisticated instruments would be more commonly used by those engaged in the production of county and national maps; the ordinary estate surveyor seems to have been reliant on more traditional means of measurement using a surveyor’s chain (invented in its present form by Edmund Gunther in 1620) and, as here, surveying poles. The chain was 22 yards long, and divided into 100 links; however the unit of linear measurement most frequently encountered in written surveys is the rod, pole or perch. In 18th century Wiltshire the length of a pole could be 15 feet, 16½ feet or 18 feet. The 16½ foot pole, of which there were four to the chain, was that most commonly used and became the standard length, but the eighteen foot pole was used for measuring woodland in many parts of Wiltshire.[11] The measuring poles described in Goddard’s field-book are thus not a standard length, and although the exact length of the first pole is indecipherable one may infer that two poles of slightly different lengths were apparently being used at Goddard’s Swindon estates. There must therefore be a degree of caution in using the measurements in Goddard’s field book.

Goddard's Concordance

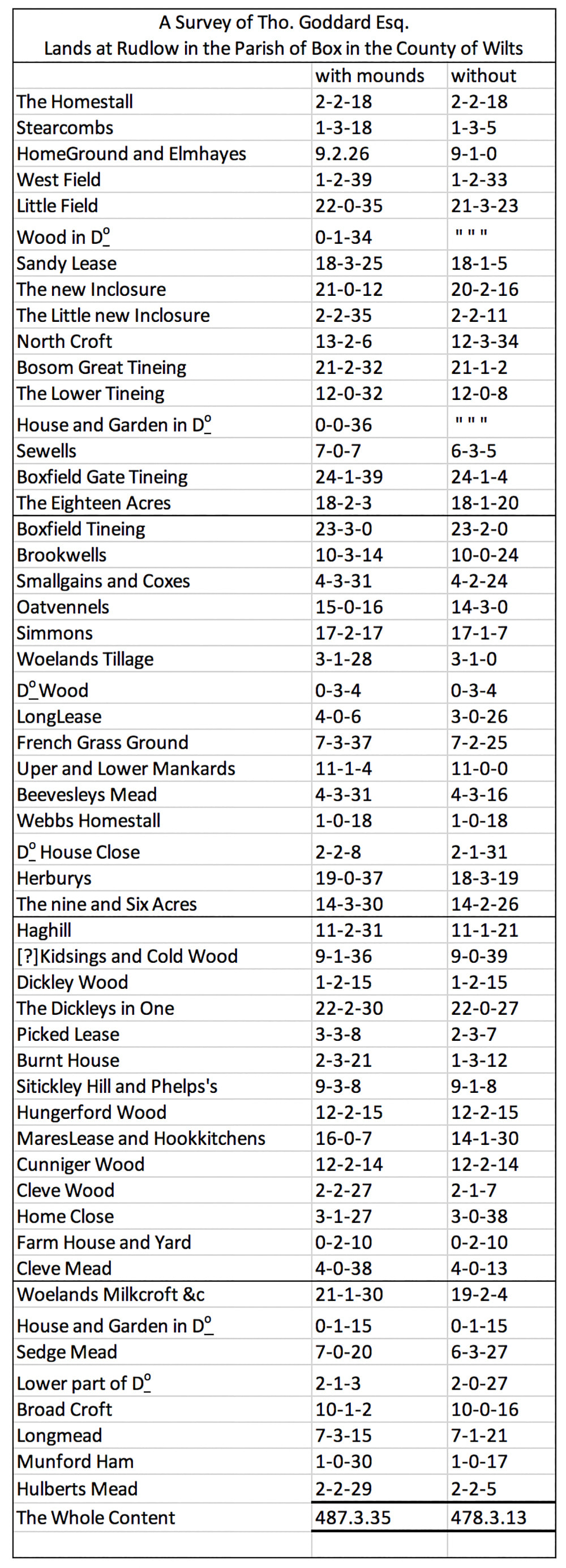

The next item in the field book is a page entitled The Concordance of Tho: Goddard Esq’ Estate in which the various sub-totals of the components of the Swindon estates are added together. This is followed by the Rudloe terrier above (undated, although as we shall see there is internal evidence that it was compiled before 1761), which is followed in turn by a Survey of Staunton lands belonging to Thomas Goddard taken the 11 Febray 1759 exclusive of the Mounds. The Staunton survey is in a somewhat less assured hand than the Swindon and Rudloe surveys (which are in what appear to be the same hand, although the script is larger in the Rudloe survey). The Staunton account is followed by A Survey of the lands belonging to Amb. Goddard in the Parish of Wanborough 1780, and finally A Survey of Southbroke Farm in the Parish of Rodbourne (undated), which is a short terrier

(11 land parcels) accompanied by a simple plan. The Wanborough and Rodbourne surveys are entered in what seems to be the same hand, possibly the same as that of the Staunton survey. The several sections of the book have thus not been added in strict chronological order of the surveys. The likelihood is that the initial Swindon entries, up to and including the concordance page were entered at the time of survey in 1763, to which transcriptions from separate, older, manuscripts in respect of Rudloe and Staunton were subsequently added, with the final sections added by Ambrose Goddard after his inheritance of the estate in 1770.

The next item in the field book is a page entitled The Concordance of Tho: Goddard Esq’ Estate in which the various sub-totals of the components of the Swindon estates are added together. This is followed by the Rudloe terrier above (undated, although as we shall see there is internal evidence that it was compiled before 1761), which is followed in turn by a Survey of Staunton lands belonging to Thomas Goddard taken the 11 Febray 1759 exclusive of the Mounds. The Staunton survey is in a somewhat less assured hand than the Swindon and Rudloe surveys (which are in what appear to be the same hand, although the script is larger in the Rudloe survey). The Staunton account is followed by A Survey of the lands belonging to Amb. Goddard in the Parish of Wanborough 1780, and finally A Survey of Southbroke Farm in the Parish of Rodbourne (undated), which is a short terrier

(11 land parcels) accompanied by a simple plan. The Wanborough and Rodbourne surveys are entered in what seems to be the same hand, possibly the same as that of the Staunton survey. The several sections of the book have thus not been added in strict chronological order of the surveys. The likelihood is that the initial Swindon entries, up to and including the concordance page were entered at the time of survey in 1763, to which transcriptions from separate, older, manuscripts in respect of Rudloe and Staunton were subsequently added, with the final sections added by Ambrose Goddard after his inheritance of the estate in 1770.

The Rudloe Survey

The inclusion of maps elsewhere in the book suggests that the Rudloe terrier might also have originally been accompanied by a map, and indeed on close inspection the single blank page immediately before the account of Rudloe is discoloured along the margin; the discolouration, which is not evident on any of the other blank pages in the book, strongly suggests that a map was once pasted in here.

The inclusion of maps elsewhere in the book suggests that the Rudloe terrier might also have originally been accompanied by a map, and indeed on close inspection the single blank page immediately before the account of Rudloe is discoloured along the margin; the discolouration, which is not evident on any of the other blank pages in the book, strongly suggests that a map was once pasted in here.

|

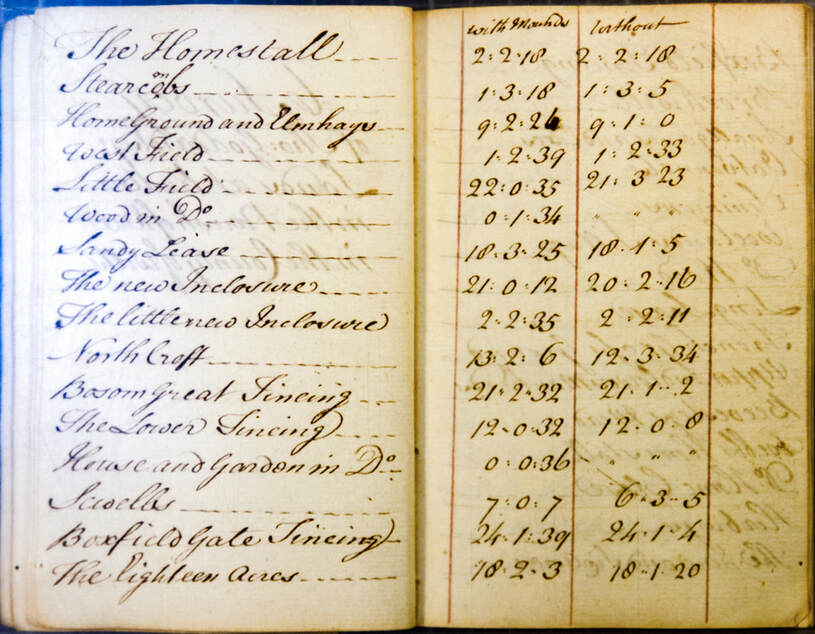

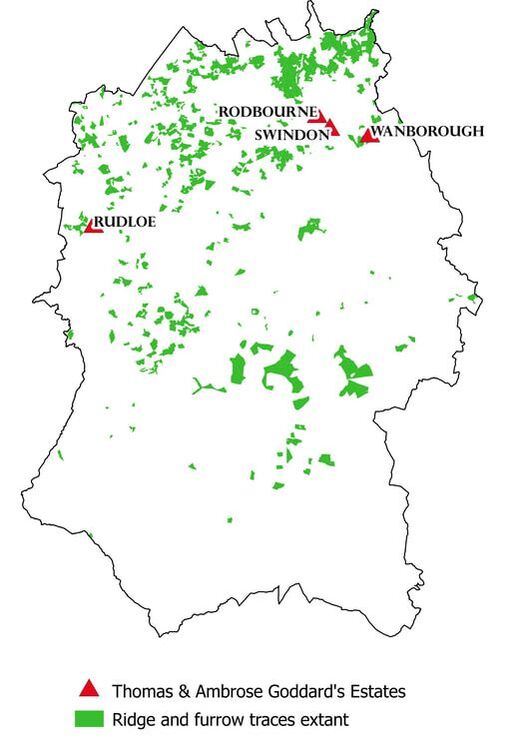

The areas of each field are given in acres, roods and perches.[12] Two measurements are given for each land parcel; one with mounds, the other without. The area with is greater than the area without, apart from a few instances (all either woodland or small plots with buildings) where the two measurements are the same. The main Swindon surveys also include two sets of measurements. 17th- and 18th-century cadastral maps were usually annotated to indicate the area of each field, and this is the case with the maps within the field-book; in each case it is the measurement without mounds that is shown on the map. (NB Throughout the following account area measurements are given in the same format as that used by Thomas Goddard; thus 2-2-18 is two acres, two roods, and eighteen perches. Unless stated otherwise, areas are without mounds). The final line The Whole Content gives a total area for all the fields. Whereas the Swindon terriers have sub-totals added up at the end of each page, and carried forward to the following page, the Rudloe terrier has no sub-totals, and in fact the totals given have both been miscalculated, the actual total of the with mounds measurements is 488 acres 2 roods 9 perches, and the total of the without mounds measurements 471 acres 0 roods 22 perches. Clearly there has been a transcription error; careful checking shows that the error was Thomas Goddard’s, or his surveyor’s, and not the present author’s! Since a map is a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional land surface, any cartographer has to find a means of converting the superficial linear measurements made across the ground surface into a plan measurement. Where the ground surface is more or less level the difference is negligible, but for hilly areas the discrepancy could be considerable. What the field-book entries apparently show are the superficial measurement of the field surface area made on the ground, and the adjusted measurement required to plot the same field on a map. The description of the ground undulations as mounds may well refer to the shallow banks which landscape archaeologists describe as ridge-and-furrow. This landform appears as a corrugation of the ground of the open fields, caused by systematic ploughing of the individual field strips which had the effect over the years of heaping up the ground towards the middle of the strip. The net result was a slight increase in land surface area, and a furrow between each strip which was beneficial for drainage; it also made the physical limit of each individual strip immediately visible to the tenants farming the open fields. |

Ridge-and-furrow is a landform particularly associated with the clay soils of the east and central Midlands, where despite the depredations of deep ploughing, especially since the second world war, there are still areas where it survives as a prominent feature of the landscape.

Ridge-and-furrow is not a landform now evident in any part of Box, and indeed it is unlikely that it was ever extensive, or even present here at all; not all open field systems developed ridge and furrow. However, Goddard’s Swindon estates were in a part of the county where there is significantly more evidence for surviving ridge and furrow;[13] the sprawl of 19th-century and later development prevents us from seeing it in the area of Goddard’s main estates but there can be little doubt that the landform was familiar to Goddard and his surveyor. One possible explanation for the ‘with mounds’ measurements is that the formulation has been used to encompass all circumstances where the surveyor had to deal with ground surface that was not horizontal, whether caused by ridge and furrow or, as is more likely in the case of Rudloe, the natural slope of the ground.

In Part 2 of this series in the next issue Jonathan uses the evidence of the terrier and two earlier documents, only very recently discovered, to reconstruct the landscape of Rudloe in the eighteenth century. Most of Rudloe lay outside the Speke and Northey estates and is thus omitted from the early 17th century maps which record the rest of the parish. An attempt to recreate the map which apparently accompanied the Goddard terrier will illuminate the development of Rudloe’s rural landscape .

References

[1] B Goddard, 1992, Sir Walter Godarville, Late of Wiltshire, http://goddardassociation.org.uk/open/magazines/23%20-%20March%201992.htm .

[2] The genealogical account here is based on JW Harms, 1990 The Goddard Book Vol 2 (Gateway, Baltimore), especially pp 627-755. Earlier parts of the family tree are at: http://www.glenncourt.com/genealogy/fam_goddard.php. Some additional information may be found in RWK Goddard, 1910, Goddard Wills (London) [transcribed 2005: http://goddardassociation.org.uk/secure/pdf/Goddard-Wills_1606-1809.pdf ].

[3] KA Rodwell, 2004, The history and structural development of Rudloe Manor, Box, Wiltshire (unpublished appraisal accompanying planning application).

[4] JPM Fowle (ed), 1955, Wiltshire Quarter Sessions and Assizes, 1736 (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Records Branch vol 11), Devizes, p.135.

[5] Goddard Wills p.60.

[6] Goddard Wills p.68.

[7] This author has, to date, been unable to ascertain the point at which the Goddards ceased to own land in Rudloe or elsewhere in Box, but it must have been before the Tithe apportionment of 1838, as they are not listed there as landowners.

[8] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre: ref 4179/1.

[9] These included commissions from St John’s College Oxford, which holds a map of Southmoor in the Parish of Longmore by Edward and Thomas Smith of Shrivenham dated 1770, one of Bagley Wood, Radley of 1771-5 (attributed to the Smiths on stylistic grounds), and one of St Giles’s parish, Oxford of 1769, also by Edward and Thomas Smith and which also has an accompanying written survey. See HM Colvin, 1950, Manuscript maps belonging to St John’s College, Oxford Oxoniensia Vol.15, 92-103: http://www.oxoniensia.org/volumes/1950/colvin.pdf .

[10] AW Richeson, 1966, English Land Measuring to 1800: Instruments and Practices (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge Mass. and London).

[11] T Davis, 1794, revised 1811, General View of the Agriculture of Wiltshire: Drawn up and published by order of the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement, p.268.

[12] On the front flyleaf of Goddard’s notebook is a note, in a different and less confident hand, which states 4 rood is an Acre,

40 lug is a Rood. Lug is an alternative term for the perch, (also known as a rod or pole); all these terms could be used as a unit of square measure as well as linear measure. There were 160 perches to the acre, so in this context a perch would have been an area of 30¼ square yards or 25.29m2, although as we have seen there was considerable local variation in the length of the rod/pole/perch. Since lugs are otherwise not referred to in the field-book, we may suppose that this aide-memoire was not inserted by Thomas or Ambrose Goddard.

[13] Report and GIS data (shapefiles) at: https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/wiltshire_hlc_2017/.

[1] B Goddard, 1992, Sir Walter Godarville, Late of Wiltshire, http://goddardassociation.org.uk/open/magazines/23%20-%20March%201992.htm .

[2] The genealogical account here is based on JW Harms, 1990 The Goddard Book Vol 2 (Gateway, Baltimore), especially pp 627-755. Earlier parts of the family tree are at: http://www.glenncourt.com/genealogy/fam_goddard.php. Some additional information may be found in RWK Goddard, 1910, Goddard Wills (London) [transcribed 2005: http://goddardassociation.org.uk/secure/pdf/Goddard-Wills_1606-1809.pdf ].

[3] KA Rodwell, 2004, The history and structural development of Rudloe Manor, Box, Wiltshire (unpublished appraisal accompanying planning application).

[4] JPM Fowle (ed), 1955, Wiltshire Quarter Sessions and Assizes, 1736 (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Records Branch vol 11), Devizes, p.135.

[5] Goddard Wills p.60.

[6] Goddard Wills p.68.

[7] This author has, to date, been unable to ascertain the point at which the Goddards ceased to own land in Rudloe or elsewhere in Box, but it must have been before the Tithe apportionment of 1838, as they are not listed there as landowners.

[8] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre: ref 4179/1.

[9] These included commissions from St John’s College Oxford, which holds a map of Southmoor in the Parish of Longmore by Edward and Thomas Smith of Shrivenham dated 1770, one of Bagley Wood, Radley of 1771-5 (attributed to the Smiths on stylistic grounds), and one of St Giles’s parish, Oxford of 1769, also by Edward and Thomas Smith and which also has an accompanying written survey. See HM Colvin, 1950, Manuscript maps belonging to St John’s College, Oxford Oxoniensia Vol.15, 92-103: http://www.oxoniensia.org/volumes/1950/colvin.pdf .

[10] AW Richeson, 1966, English Land Measuring to 1800: Instruments and Practices (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge Mass. and London).

[11] T Davis, 1794, revised 1811, General View of the Agriculture of Wiltshire: Drawn up and published by order of the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement, p.268.

[12] On the front flyleaf of Goddard’s notebook is a note, in a different and less confident hand, which states 4 rood is an Acre,

40 lug is a Rood. Lug is an alternative term for the perch, (also known as a rod or pole); all these terms could be used as a unit of square measure as well as linear measure. There were 160 perches to the acre, so in this context a perch would have been an area of 30¼ square yards or 25.29m2, although as we have seen there was considerable local variation in the length of the rod/pole/perch. Since lugs are otherwise not referred to in the field-book, we may suppose that this aide-memoire was not inserted by Thomas or Ambrose Goddard.

[13] Report and GIS data (shapefiles) at: https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/wiltshire_hlc_2017/.