The New Road, 1761 Alan Payne February 2019

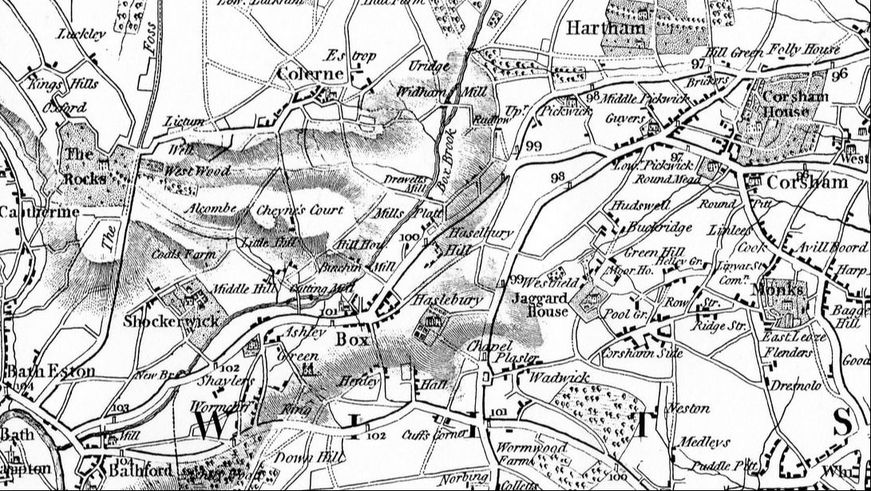

To understand Box before 1761, go to Chapel Plaister and look around. You are on the route of the medieval road from London to Bath running along an ancient ridgeway via Kingsdown. Box Valley lies 120 feet below, hidden from view. This was the closest that most travellers ever got to Box village. A signpost on Bowden’s 1720 map stated: For Box, turn in at the gate.[1] Everything changed after 1761. Instead of being a rural retreat, the village became acutely conscious of its importance on a national highway, symbolised by a milestone on the Bradford Road from the late 1700s, which announced: Hyde Park Corner 100 miles - 7 miles from Bath.[2]

|

Turnpike Acts of Parliament

The initiative for new roads often came from local business men concerned with small sections of the highway, who petitioned Parliament to improve their section. If agreed, Parliament granted the turnpike trustees certain property rights (usually for 21 years), including the right to charge tolls for traffic using the route, in return for the trustees maintaining the section of road out of the income arising. The turnpike roads had gates or barriers (pikes) across the highway which had to be opened (turned) and the toll paid before access was granted. Horse-riders, long distance coaches, carriages, wagons and animals had to pay. Free passage was allowed to the royal family, soldiers, agricultural equipment, funeral processions and pedestrians.[3] The authorities in Bath recognised that tolls would harm its tourist trade and so they reimbursed day trippers.[4] |

The process was expensive to set up. As well as legal costs, sometimes road widening or property demolition had to be funded in advance by subscribers.[5] The trustees often included notable local people (Justices of the Peace, Members of Parliament and local officials) to impress prospective subscribers.[6] They placed adverts in newspapers inviting local subscriptions in the form of bonds or mortgages in return for interest (usually 4.5%) because they were not allowed to issue a share capital (unlike the railways). Subscribers were mostly local gentlemen, landowners and those with a commercial interest.[7] Paid officials were appointed: a clerk (usually a local solicitor), treasurer (bank manager) and surveyors, who were responsible for appointing toll collectors and organising repair work.[8] There were also costs of erecting gates and constructing a toll house. Usually the trust farmed out sections of the road for periods of 3 years with each gate going to the highest bidder.

The toll collectors (gatekeepers) had a very difficult job. They had to interpret a huge range of tolls and extra tariffs, measure wagon widths and estimate cart weights. Different charges applied to wagons with wheels of 12 inches, 9, 6 and less and for each category different rates were applicable for the number of horses from eight down to one.[9] To restrict wagons which would damage the highway, the government brought in additional tariffs for certain vehicles and winter supplements. All of this took place in the face of deliberate deception by travellers. In addition, they had to keep distinct accounts to report to the trustees.[10]

From the outset there was considerable local opposition to turnpikes. Counter petitions were made by drovers, carriers, stagecoach owners and merchants who resented charges to access routes that had been free for centuries. There were popular riots (called Rebecca Riots) usually led by a man dressed in woman's clothing. From the 1720s to the 1740s there were riots in Somerset and Gloucester which in 1749 led to a regiment of dragoons being called up to put down disruption at Kingswood, Bristol.[11] The punishment for destruction of toll gates was increased to 7 years transportation or death without clergy after 1734. Originally turnpikes were envisaged as a temporary solution to supplement the work of the parish and they were allowed some of the statutory parish income to do the repairs, either labour or cash. They were usually authorised for 21 years after which the road was returned to the parish.[12]

The toll collectors (gatekeepers) had a very difficult job. They had to interpret a huge range of tolls and extra tariffs, measure wagon widths and estimate cart weights. Different charges applied to wagons with wheels of 12 inches, 9, 6 and less and for each category different rates were applicable for the number of horses from eight down to one.[9] To restrict wagons which would damage the highway, the government brought in additional tariffs for certain vehicles and winter supplements. All of this took place in the face of deliberate deception by travellers. In addition, they had to keep distinct accounts to report to the trustees.[10]

From the outset there was considerable local opposition to turnpikes. Counter petitions were made by drovers, carriers, stagecoach owners and merchants who resented charges to access routes that had been free for centuries. There were popular riots (called Rebecca Riots) usually led by a man dressed in woman's clothing. From the 1720s to the 1740s there were riots in Somerset and Gloucester which in 1749 led to a regiment of dragoons being called up to put down disruption at Kingswood, Bristol.[11] The punishment for destruction of toll gates was increased to 7 years transportation or death without clergy after 1734. Originally turnpikes were envisaged as a temporary solution to supplement the work of the parish and they were allowed some of the statutory parish income to do the repairs, either labour or cash. They were usually authorised for 21 years after which the road was returned to the parish.[12]

The Kingsdown Turnpike

The Corsham-Box turnpike wasn't the first Georgian road improvement in the area. When Queen Anne took the air at Kingsdown on a visit to Bath in 1706 there was an accident witnessed by the author Daniel Defoe: On the NW of this city (Bath) up a very steep hill, is the King’s Down, where sometimes persons of quality who have coaches go up for air .. And the hill up to the Downs is so steep, that the late Queen Anne was extremely frightened in going up, her coachman stopping to give the horses breath, and the coach wanting a dragstaff (braking mechanism), ran back in spite of all the coachman’s skill; the horses not being brought to strain the harness again, or guards behind it into utmost confusion, until the servants setting their heads and shoulders to the wheels, stopped them by plain force.[13]

That led to demands for the urgent repair of the medieval highway from London. The popularity of Beau Nash's Bath after 1705; the demands of Wiltshire's traders for cheaper transport for their exports; and the general growth of trade, towns and population led to five Acts of Parliament in the first quarter of the century covering different sections of the road.[14]

The Corsham-Box turnpike wasn't the first Georgian road improvement in the area. When Queen Anne took the air at Kingsdown on a visit to Bath in 1706 there was an accident witnessed by the author Daniel Defoe: On the NW of this city (Bath) up a very steep hill, is the King’s Down, where sometimes persons of quality who have coaches go up for air .. And the hill up to the Downs is so steep, that the late Queen Anne was extremely frightened in going up, her coachman stopping to give the horses breath, and the coach wanting a dragstaff (braking mechanism), ran back in spite of all the coachman’s skill; the horses not being brought to strain the harness again, or guards behind it into utmost confusion, until the servants setting their heads and shoulders to the wheels, stopped them by plain force.[13]

That led to demands for the urgent repair of the medieval highway from London. The popularity of Beau Nash's Bath after 1705; the demands of Wiltshire's traders for cheaper transport for their exports; and the general growth of trade, towns and population led to five Acts of Parliament in the first quarter of the century covering different sections of the road.[14]

|

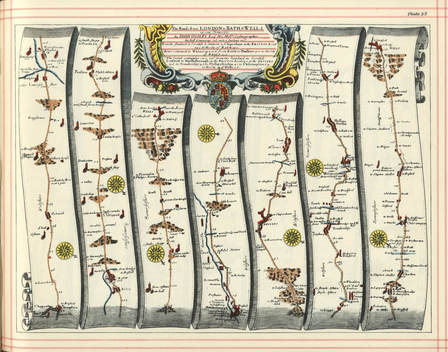

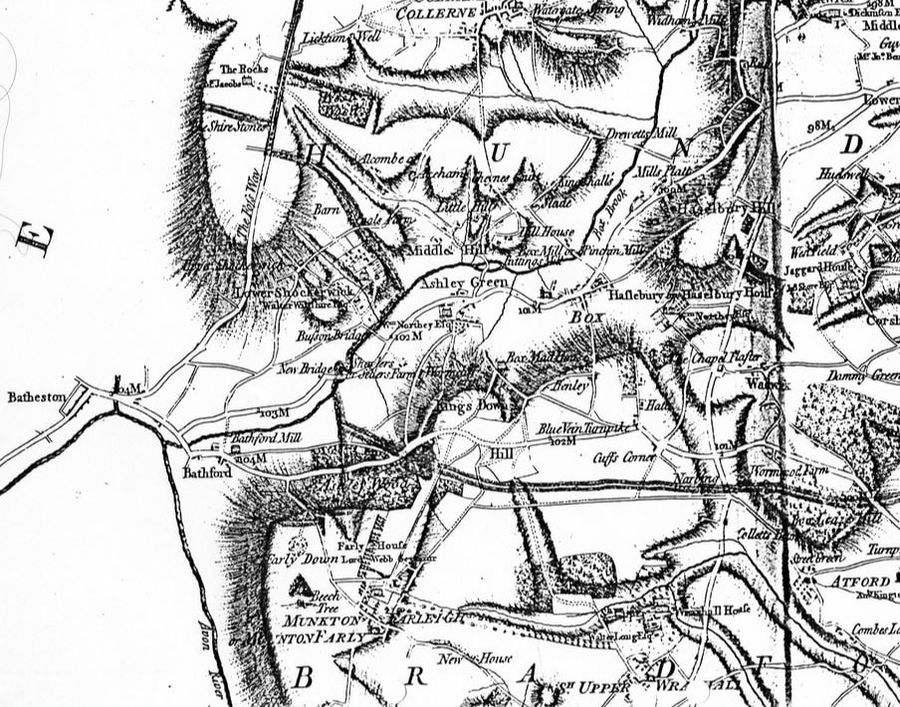

An Act of Parliament of 1706-7 specified as a priority the section from Batheaston, through Bathford, to the top of Kingsdown Hill, five miles in length. The route is clearly marked on John Ogilby's map of 1675. As we have seen this was an important section of road because several different routes converged before the Kingsdown road west to Bath. The work was very piecemeal, other parts of the route being completed much later. The middle route from Lacock via Corsham, Chapel Plaister, Blue Vein to Kingsdown was turnpiked in 1745.[15] Even then the route was unsatisfactory because the road was too narrow in places and funds were not available to buy properties alongside the highway.

Left: Andrews' and Dury's map of 1773 showing the road from Batheaston to Kingsdown (courtesy Wilts History Centre) |

Box's London Road Turnpike, 1761

The length of the new road was measured as 7 miles from Corsham to Kingsdown and Bath Easton and the trustees raised a debt of £4,900 to fund the work.[16] By December 1761, the work was complete and The Bath Journal announced: The New Turnpike Road leading from Bath through Box to Chippenham, Calne and Marlborough is now completed and opened, reducing the distance by 1½ miles.[17] A tollhouse and gate were built at the entrance to the village (long since demolished). Passenger demand grew, encouraged by improvements in coach design and carriage springs and many travelled on the mail coaches. By 1800, travel time had fallen from three days to one day.[18] In 1806 the itinerary ran: depart Bath 5.30pm; depart Chippenham 7.05pm; arrive London 7am.

The new road wasn't really for Box visitors but for those using the entire route to access Bath. For this reason, the tolls were auctioned for the whole route, rather than for specific gates.[19] There is no contemporary report about the location of the Box turnpike but a later reference indicates that a turnpike house existed in the area of the current Box Post Office.[20] The road changed Box’s importance and its economic life. Henceforth the village became a stopping point for a change of horses and a wash and brush-up before entering Bath society. Half way up the valley side at Box Hill, London Road split the old communal Box Fields, separated Hazelbury from its medieval connection with the Box Mill, and by-passed the Market Place which lost much of its original purpose. Most of the turnpike trusts were created in the decades from the 1750s to 1770s when over 11,000 miles of road were turnpiked as the initiative became a craze.[21] In the period 1751 to 1758 in Wiltshire alone sixteen new trusts were approved to give better transport facilities for textiles, coal and tourists.[22]

The new turnpike road was developed piecemeal. The Chippenham Trust built a section from Chippenham to Pickwick, avoiding Corsham in 1743 and advertised it as the new Bath Road.[23] But this route still went via Chapel Plaister and Kingsdown into Bath. It was in 1756 that a more direct route was proposed from Pickwick, cutting right through Hartham Park, owned by Thomas Duckett MP for Calne, and down Box Hill.[24] A new trust was formed to promote the road named Bricker’s Barn Trust, after a property at the Cross Keys Inn, Pickwick. The name was still referenced in the top right of the 1792 map at the headline of this article.

The length of the new road was measured as 7 miles from Corsham to Kingsdown and Bath Easton and the trustees raised a debt of £4,900 to fund the work.[16] By December 1761, the work was complete and The Bath Journal announced: The New Turnpike Road leading from Bath through Box to Chippenham, Calne and Marlborough is now completed and opened, reducing the distance by 1½ miles.[17] A tollhouse and gate were built at the entrance to the village (long since demolished). Passenger demand grew, encouraged by improvements in coach design and carriage springs and many travelled on the mail coaches. By 1800, travel time had fallen from three days to one day.[18] In 1806 the itinerary ran: depart Bath 5.30pm; depart Chippenham 7.05pm; arrive London 7am.

The new road wasn't really for Box visitors but for those using the entire route to access Bath. For this reason, the tolls were auctioned for the whole route, rather than for specific gates.[19] There is no contemporary report about the location of the Box turnpike but a later reference indicates that a turnpike house existed in the area of the current Box Post Office.[20] The road changed Box’s importance and its economic life. Henceforth the village became a stopping point for a change of horses and a wash and brush-up before entering Bath society. Half way up the valley side at Box Hill, London Road split the old communal Box Fields, separated Hazelbury from its medieval connection with the Box Mill, and by-passed the Market Place which lost much of its original purpose. Most of the turnpike trusts were created in the decades from the 1750s to 1770s when over 11,000 miles of road were turnpiked as the initiative became a craze.[21] In the period 1751 to 1758 in Wiltshire alone sixteen new trusts were approved to give better transport facilities for textiles, coal and tourists.[22]

The new turnpike road was developed piecemeal. The Chippenham Trust built a section from Chippenham to Pickwick, avoiding Corsham in 1743 and advertised it as the new Bath Road.[23] But this route still went via Chapel Plaister and Kingsdown into Bath. It was in 1756 that a more direct route was proposed from Pickwick, cutting right through Hartham Park, owned by Thomas Duckett MP for Calne, and down Box Hill.[24] A new trust was formed to promote the road named Bricker’s Barn Trust, after a property at the Cross Keys Inn, Pickwick. The name was still referenced in the top right of the 1792 map at the headline of this article.

Changes Brought by the Road

It is difficult to imagine Box in its present form without a road from the east. Before the road, Box was a nucleated settlement concentrated on the area around Box Church and the Market Place with scattered hamlets, the most important of which were the routes going to the Bath-London Road through Ashley Lane.

The road changed the whole layout of the village. The Victorian school, the housing estates of the 1900s at Bargates and The Bassetts, and the doctors’ surgery at the end of the twentieth century are all ribbon development along the turnpike road. It is hard to overestimate the change. With the old medieval road system most travellers kept to the high ground through Kingsdown, away from the isolated village of Box which lay in the valley down twisting, un-signposted tracks, frequently dividing and offering a bewildering choice to the uninitiated.

For the first time, Box could be accessed from the east which opened up the village's expansion beyond Mill Lane into the old common fields. Previously, the only visitors to the village came by arrangement because Box was so far off the beaten path. After the road, Box became a regular stopping point on a national highway from London to Bath. For Box, it was a development which brought trade, property development and unexpected wealth. Box ceased to be an inward-based economy and began to be part of national trade.

It is difficult to imagine Box in its present form without a road from the east. Before the road, Box was a nucleated settlement concentrated on the area around Box Church and the Market Place with scattered hamlets, the most important of which were the routes going to the Bath-London Road through Ashley Lane.

The road changed the whole layout of the village. The Victorian school, the housing estates of the 1900s at Bargates and The Bassetts, and the doctors’ surgery at the end of the twentieth century are all ribbon development along the turnpike road. It is hard to overestimate the change. With the old medieval road system most travellers kept to the high ground through Kingsdown, away from the isolated village of Box which lay in the valley down twisting, un-signposted tracks, frequently dividing and offering a bewildering choice to the uninitiated.

For the first time, Box could be accessed from the east which opened up the village's expansion beyond Mill Lane into the old common fields. Previously, the only visitors to the village came by arrangement because Box was so far off the beaten path. After the road, Box became a regular stopping point on a national highway from London to Bath. For Box, it was a development which brought trade, property development and unexpected wealth. Box ceased to be an inward-based economy and began to be part of national trade.

Goods in the Horse-Drawn Era

The opening of the London Road in Box brought considerable new trade to the village. A regular goods-carrying service using four-wheeled carriers' wagons started about 1770 transporting goods between London and Bristol to a timetable two or three times a week. Many of the turnpike roads were the initiative of merchants and manufacturers keen to convey their goods to a wider audience. By the end of the 1700s the whole country was connected by a turnpike and trackway system for horse-drawn traffic. In Box, it was all that was available as the By Brook was unsuitable during times of adverse weather and the canal system was too far away. Locally, the carriage trade made the fortune of the Wiltshire family who built Shockerwick House in 1775. Walter Wiltshire (1719 - 1799) was a major haulier on the London to Bath / Bristol route with his Wiltshire's Flying Waggons.[25] Walter was a trustee of the Bath Turnpike Roads after 1757 and friend of painter Thomas Gainsborough who gave him the painting The Harvest Waggon in 1774. Walter was later buried in Woolley Church.

At the forefront of the transport revolution was the development of the wagon, a heavy, four-wheeled, covered vehicle which replaced both the pack-horse and the unstable, two-wheeled cart, which had been in general use from the late 1500s. It has been claimed that the wagon was the greatest advance in carriage on farms before the internal combustion engine. [26] Wagons were outlawed in 1618 to prevent damage on roads but were in general use by 1681.[27] County carriers linked market towns and cities with individual villages bringing goods and parcels to local depots and carrying local farm produce to markets. In the mid-1700s Bath had eleven different firms offering 14 services per week within a 30-mile radius.[28] The opening of the London Road to Corsham encouraged the amount of wagon trade to Box because traffic from the Old Bath Roads (on the medieval ridgeway routes) was often bogged down in adverse weather.

In the village local carriers delivered goods which had been bought described by the phrase a packet of needles for Mrs This and a new teapot for Mrs That.[29] The carrier’s dog was an important part of the system, guarding the goods in wagons at delivery points such as inns and public places. In Box the Browning family was an extensive local haulier of general goods (sometimes called fly carriers prepared to carry people and goods), whilst the Goulstone family started as local stone hauliers. The wagon trade and the London Road were vital in the development of Box village, feeding shops with foods, letters and information from the rest of the country. The importance of the traffic was appreciated early on when Justices of the Peace were instructed to set maximum carriage rates in their area in 1692. In Wiltshire the rate was often 12d per ton per mile with higher rates for small parcels.[30] The rates were additional to the turnpike tolls. The tolls to be charged were a shilling for a coach or other vehicle drawn by more than two horses, sixpence for one drawn by one or two horses, a penny for a horse, ten pence for every score of oxen or cattle, and five pence for every score of sheep or lambs. An exception was made in the case of people going up the hill to take the air.[31]

The opening of the London Road in Box brought considerable new trade to the village. A regular goods-carrying service using four-wheeled carriers' wagons started about 1770 transporting goods between London and Bristol to a timetable two or three times a week. Many of the turnpike roads were the initiative of merchants and manufacturers keen to convey their goods to a wider audience. By the end of the 1700s the whole country was connected by a turnpike and trackway system for horse-drawn traffic. In Box, it was all that was available as the By Brook was unsuitable during times of adverse weather and the canal system was too far away. Locally, the carriage trade made the fortune of the Wiltshire family who built Shockerwick House in 1775. Walter Wiltshire (1719 - 1799) was a major haulier on the London to Bath / Bristol route with his Wiltshire's Flying Waggons.[25] Walter was a trustee of the Bath Turnpike Roads after 1757 and friend of painter Thomas Gainsborough who gave him the painting The Harvest Waggon in 1774. Walter was later buried in Woolley Church.

At the forefront of the transport revolution was the development of the wagon, a heavy, four-wheeled, covered vehicle which replaced both the pack-horse and the unstable, two-wheeled cart, which had been in general use from the late 1500s. It has been claimed that the wagon was the greatest advance in carriage on farms before the internal combustion engine. [26] Wagons were outlawed in 1618 to prevent damage on roads but were in general use by 1681.[27] County carriers linked market towns and cities with individual villages bringing goods and parcels to local depots and carrying local farm produce to markets. In the mid-1700s Bath had eleven different firms offering 14 services per week within a 30-mile radius.[28] The opening of the London Road to Corsham encouraged the amount of wagon trade to Box because traffic from the Old Bath Roads (on the medieval ridgeway routes) was often bogged down in adverse weather.

In the village local carriers delivered goods which had been bought described by the phrase a packet of needles for Mrs This and a new teapot for Mrs That.[29] The carrier’s dog was an important part of the system, guarding the goods in wagons at delivery points such as inns and public places. In Box the Browning family was an extensive local haulier of general goods (sometimes called fly carriers prepared to carry people and goods), whilst the Goulstone family started as local stone hauliers. The wagon trade and the London Road were vital in the development of Box village, feeding shops with foods, letters and information from the rest of the country. The importance of the traffic was appreciated early on when Justices of the Peace were instructed to set maximum carriage rates in their area in 1692. In Wiltshire the rate was often 12d per ton per mile with higher rates for small parcels.[30] The rates were additional to the turnpike tolls. The tolls to be charged were a shilling for a coach or other vehicle drawn by more than two horses, sixpence for one drawn by one or two horses, a penny for a horse, ten pence for every score of oxen or cattle, and five pence for every score of sheep or lambs. An exception was made in the case of people going up the hill to take the air.[31]

Coaching Inns

The new road also helped to develop new buildings in the village. New Flyers coaches offering speed to travellers demanded quick and efficient pit-stop changes. Above all it was the coaching inns that profited. The new travel relied upon fresh horses every 10 miles or so and looked to Box’s coaching inns to provide a change of animals between Bath and Chippenham. Up to 50 change horses were needed for the coaches and for hiring out with chaises to travellers who alighted in Box.[32] Getting the horses harnessed caused a great commotion as they had to be carefully paired for equal strides to avoid excessive jolting when moving but passengers who alighted were jostled and surrounded by purveyors of goods.

Box’s coaching inns flourished and promoted themselves by installing fine inn signs outside their premises. Because of their closeness to Bath, the local inns rarely provided accommodation but they had fine dining rooms in the back often having a porch and a low window for the benefit of travelling ladies. These rooms became assembly points for locals for dances, playing cards and formal functions like public proclamations and elections.[33] The new road didn't end all other traffic and a turnpike still existed on the old medieval road in 1791 when the Blue Vein gate raised a profit of £342.2s.6d.[34]

The Queen’s Head building predates the London Road with a date of 1709 on the cellar door.[35] It soon adjusted to cater for the passing traffic. The stable block of the Queen’s is opposite the pub, once a public lavatory and now a private residence, and Byways in Chapel Lane was the site of the ostler’s cottage for the inn.[36] The Queen’s Head flourished in the new economic circumstances and was substantially redeveloped in the late 1700s.

The Bear Inn (sometimes called Bayley’s Inn) and the three Bear Inn Cottages also originated before the turnpike road. During the 1700s the parish vestry meetings were held in the pub as a convenient meeting place open and accessible to the public. The pub expanded as a result of the turnpike road and Box Pharmacy on the opposite side of the road was used as the stables.

Coach travel needs brought new trades to the village, horse ostlers, wheelwrights and farriers, all highly profitable skills. The usual charge for a pair of horses was 1s a mile for distances less than 12 miles.[37] Special terms were offered for stabling and accommodation to encourage local trade. Letters were carried for 4d for up to 15 miles and for 9d up to 100 miles. Most travellers were wealthy if they could afford the return fare of £1.8s.0d and the village had a chance to do business with them.[38] Trade increased eight-fold between 1775 and 1835.

Demise of the Turnpikes

The turnpike roads didn't mean better road surfaces, which still became uneven when stones on the rough surface were thrown to the side by passing vehicles. The main difficulty was how to treat water disturbing the road surface. Incredibly to our modern views, the solution proposed by the engineers was to run more water on the road surface to damp down the dust and to wash it away leaving a hard floor. It was argued that this would replicate the process in the bed of a stream.[39]

We still have evidence of these ideas. There are remains of water pumps on several properties along the old Kingsdown ridgeway route. These were positioned at about two mile intervals to tap into underground springs and water the dusty surface of the road. There are the remains of one well on the roadside at the sharp corner of Old Jockey. To control charges per mile made by the coaches, milestones became common after 1720 and became a legal requirement after the Turnpike Act of 1766. The headline illustration shows where the mileposts were situated in the Box area to allow passengers to check and driver to follow the correct path. The occasional milestone can still be seen on the old ridgeway Bath Road.

The demise of the turnpike system came in a strange way whereby the control of the routes was devolved onto public finances whilst the roads themselves continued largely unchanged. By the 1820s it was apparent that the Bricker's Barn Trust was inadequate for maintaining the whole route, especially the section between Box and Bath and a new trust, the Bath Turnpike Trust proposed amendments. In 1827 a major improvement was planned, including a new line of road from the bridge near (the home of John Wiltshire, Esq, at Shockerwick House) and thence up the Box valley to or near the point where the Bradford and Pickwick roads cross the road leading from Bath to Melksham.[40] We often believe that the present route of the A4 was due to the railways but it is apparent that there were earlier plans to simplify the route through Box.

The new road also helped to develop new buildings in the village. New Flyers coaches offering speed to travellers demanded quick and efficient pit-stop changes. Above all it was the coaching inns that profited. The new travel relied upon fresh horses every 10 miles or so and looked to Box’s coaching inns to provide a change of animals between Bath and Chippenham. Up to 50 change horses were needed for the coaches and for hiring out with chaises to travellers who alighted in Box.[32] Getting the horses harnessed caused a great commotion as they had to be carefully paired for equal strides to avoid excessive jolting when moving but passengers who alighted were jostled and surrounded by purveyors of goods.

Box’s coaching inns flourished and promoted themselves by installing fine inn signs outside their premises. Because of their closeness to Bath, the local inns rarely provided accommodation but they had fine dining rooms in the back often having a porch and a low window for the benefit of travelling ladies. These rooms became assembly points for locals for dances, playing cards and formal functions like public proclamations and elections.[33] The new road didn't end all other traffic and a turnpike still existed on the old medieval road in 1791 when the Blue Vein gate raised a profit of £342.2s.6d.[34]

The Queen’s Head building predates the London Road with a date of 1709 on the cellar door.[35] It soon adjusted to cater for the passing traffic. The stable block of the Queen’s is opposite the pub, once a public lavatory and now a private residence, and Byways in Chapel Lane was the site of the ostler’s cottage for the inn.[36] The Queen’s Head flourished in the new economic circumstances and was substantially redeveloped in the late 1700s.

The Bear Inn (sometimes called Bayley’s Inn) and the three Bear Inn Cottages also originated before the turnpike road. During the 1700s the parish vestry meetings were held in the pub as a convenient meeting place open and accessible to the public. The pub expanded as a result of the turnpike road and Box Pharmacy on the opposite side of the road was used as the stables.

Coach travel needs brought new trades to the village, horse ostlers, wheelwrights and farriers, all highly profitable skills. The usual charge for a pair of horses was 1s a mile for distances less than 12 miles.[37] Special terms were offered for stabling and accommodation to encourage local trade. Letters were carried for 4d for up to 15 miles and for 9d up to 100 miles. Most travellers were wealthy if they could afford the return fare of £1.8s.0d and the village had a chance to do business with them.[38] Trade increased eight-fold between 1775 and 1835.

Demise of the Turnpikes

The turnpike roads didn't mean better road surfaces, which still became uneven when stones on the rough surface were thrown to the side by passing vehicles. The main difficulty was how to treat water disturbing the road surface. Incredibly to our modern views, the solution proposed by the engineers was to run more water on the road surface to damp down the dust and to wash it away leaving a hard floor. It was argued that this would replicate the process in the bed of a stream.[39]

We still have evidence of these ideas. There are remains of water pumps on several properties along the old Kingsdown ridgeway route. These were positioned at about two mile intervals to tap into underground springs and water the dusty surface of the road. There are the remains of one well on the roadside at the sharp corner of Old Jockey. To control charges per mile made by the coaches, milestones became common after 1720 and became a legal requirement after the Turnpike Act of 1766. The headline illustration shows where the mileposts were situated in the Box area to allow passengers to check and driver to follow the correct path. The occasional milestone can still be seen on the old ridgeway Bath Road.

The demise of the turnpike system came in a strange way whereby the control of the routes was devolved onto public finances whilst the roads themselves continued largely unchanged. By the 1820s it was apparent that the Bricker's Barn Trust was inadequate for maintaining the whole route, especially the section between Box and Bath and a new trust, the Bath Turnpike Trust proposed amendments. In 1827 a major improvement was planned, including a new line of road from the bridge near (the home of John Wiltshire, Esq, at Shockerwick House) and thence up the Box valley to or near the point where the Bradford and Pickwick roads cross the road leading from Bath to Melksham.[40] We often believe that the present route of the A4 was due to the railways but it is apparent that there were earlier plans to simplify the route through Box.

References

[1] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.9

[2] See article Historic Buildings

[3] Richard Moore-Colyer, Roads and Trackways of Wales, 2007, Landmark Publishing Ltd, p.134

[4] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, 1968, David & Charles, p.44

[5] In 1827 £10,000 was spent on land for a turnpike trust in Bath: John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic, p.37

[6] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, 1972, Cambridge University Press, p.57

[7] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, p.93

[8] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, p.74-77

[9] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, p.41-42

[10] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, p.40

[11] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, p.28

[12] Eric Pawson, The Turnpike Trusts of the Eighteenth Century, 1977, New York Academic Press, p.13

[13] Daniel Defoe quoted in Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, 1983, Countryside Books, p.35

[14] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, p.37

[15] Geoffrey N Wright, Roads and Trackways of Wessex, 1988, Ashbourne, p.151

[16] Select Reports and Papers of House of Commons, Public works, Vol 38, The Turnpike Roads in England and Wales, 1836, p.236

[17] The Bath Journal quoted in Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath p.40

[18] Geoffrey N Wright, Roads and Trackways of Wessex, p.171

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 24 November 1803

[20} 1840 Tithe Apportionment map and report

[21] Eric Pawson, The Turnpike Trusts of the Eighteenth Century, p.15

[22] Eric Pawson, The Turnpike Trusts of the Eighteenth Century, p.30

[23] Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, p.65

[24] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, published John Poulsom, 1989, p.10

[25] Brenda J Buchanan, Walter Wiltshire, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004, Oxford University Press

[26] Dorian Gerhold quoting S Porter in Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.xiv

[27] Dorian Gerhold, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.141

[28] GL Turnball, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.33

[29] Alan Everitt, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.2

[30] TS Willan, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.102

[31] Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, 1983, Countryside Books, p.34

[32] Sir William Addison, The Old Roads of England, p.120-7

[33] Sir William Addison, The Old Roads of England, p.129

[34] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 12 January 1792

[35] Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England - Wiltshire, 1975, Penguin Books, p.220

[36] WI leaflet

[37] Geoffrey N Wright, Roads and Trackways of Wessex, p.176-8

[38] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic, p.111

[39] Sir William Addison, The Old Roads of England, 1980, Harper Collins, p.115

[40] The Bath Chronicle, 22 November 1827 and 20 November 1828

[1] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.9

[2] See article Historic Buildings

[3] Richard Moore-Colyer, Roads and Trackways of Wales, 2007, Landmark Publishing Ltd, p.134

[4] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, 1968, David & Charles, p.44

[5] In 1827 £10,000 was spent on land for a turnpike trust in Bath: John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic, p.37

[6] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, 1972, Cambridge University Press, p.57

[7] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, p.93

[8] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, p.74-77

[9] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, p.41-42

[10] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, p.40

[11] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, p.28

[12] Eric Pawson, The Turnpike Trusts of the Eighteenth Century, 1977, New York Academic Press, p.13

[13] Daniel Defoe quoted in Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, 1983, Countryside Books, p.35

[14] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, p.37

[15] Geoffrey N Wright, Roads and Trackways of Wessex, 1988, Ashbourne, p.151

[16] Select Reports and Papers of House of Commons, Public works, Vol 38, The Turnpike Roads in England and Wales, 1836, p.236

[17] The Bath Journal quoted in Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath p.40

[18] Geoffrey N Wright, Roads and Trackways of Wessex, p.171

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 24 November 1803

[20} 1840 Tithe Apportionment map and report

[21] Eric Pawson, The Turnpike Trusts of the Eighteenth Century, p.15

[22] Eric Pawson, The Turnpike Trusts of the Eighteenth Century, p.30

[23] Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, p.65

[24] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, published John Poulsom, 1989, p.10

[25] Brenda J Buchanan, Walter Wiltshire, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004, Oxford University Press

[26] Dorian Gerhold quoting S Porter in Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.xiv

[27] Dorian Gerhold, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.141

[28] GL Turnball, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.33

[29] Alan Everitt, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.2

[30] TS Willan, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press, p.102

[31] Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, 1983, Countryside Books, p.34

[32] Sir William Addison, The Old Roads of England, p.120-7

[33] Sir William Addison, The Old Roads of England, p.129

[34] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 12 January 1792

[35] Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England - Wiltshire, 1975, Penguin Books, p.220

[36] WI leaflet

[37] Geoffrey N Wright, Roads and Trackways of Wessex, p.176-8

[38] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic, p.111

[39] Sir William Addison, The Old Roads of England, 1980, Harper Collins, p.115

[40] The Bath Chronicle, 22 November 1827 and 20 November 1828