Tithe Apportionment, 1836–40 Jonathan Parkhouse and Alan Payne September 2019

Maps courtesy Wiltshire History Centre and references to Know Your Place [1]

Maps courtesy Wiltshire History Centre and references to Know Your Place [1]

The Tithe Apportionment Acts signalled the end of a relationship between villagers and the established church which had existed over a thousand years. The ending of the system, of course, reflected the society which had previously existed in the village, more than the future. Originally, tithes were payment-in-kind of farm produce to support the parish church and its clergyman of one-tenth of crops, animals and derivatives such as eggs, milk, wood, wool and flour. We can see the old tithe system in Box from the 1704 Terrier (survey) of the area.

| terrier_1704.doc | |

| File Size: | 28 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

The 1704 document shows that some tithes were being paid in cash rather than produce. A variety of local arrangements had evolved in different places, whilst application of the law by the courts was inconsistent, sanctioning both evasion by tithe payers and oppression by the church. Often tithes had been commuted to cash payments as part of the process of parliamentary enclosure, although in the case of Box enclosure was a piecemeal affair over many years rather than an event procured by parliamentary process.

The tithes were divided between the rector, who received the Great Tithes of corn, grain, hay and wood, and the vicar, who got the Lesser Tithes (the rest). After the dissolution of the monasteries, many rectorial tithes were acquired by laymen (usually called the impropriator). The repairing of the chancel of the church was a liability of the impropriator and usually paid out of the rectorial tithes. In Box the impropriators were mostly the Northey family, although the Fuller family had bought a small amount of the tithes. The vicar, Rev HDCS Horlock, took most of the rest of the tithes. He lived in some luxury at Box House, next to the church, built by his ancestors. The tithe system had become an obvious anachronism by the end of the Georgian period, not applied to manufacturing or mining enterprises, resented by non-conformists, and it hurt farmers in the depression of the 1830s.

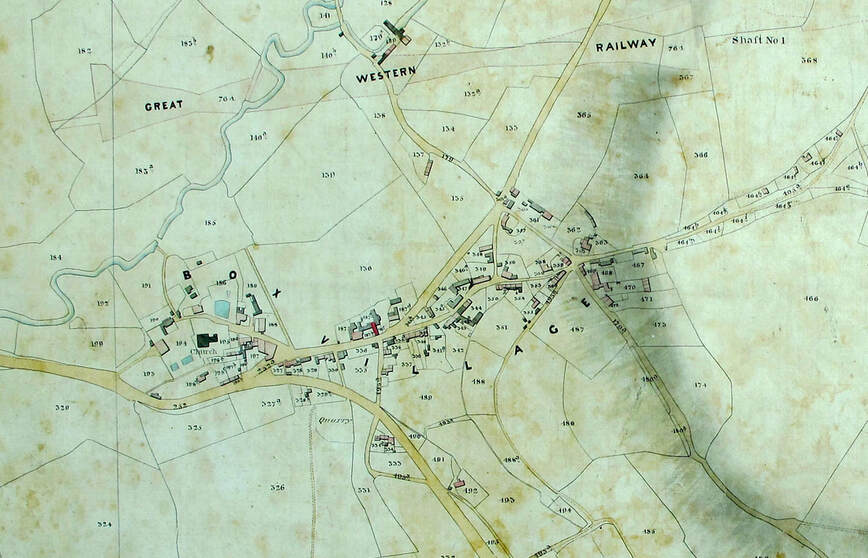

The abandonment of the system was a long and complicated national project, which took four years to achieve. Maps were drawn and re-drawn and three copies of the final award were made, for the parish, diocese and the Tithe Commission. As all this was happening, people died, land was divided and the railways and new roads came through Box splitting fields and creating a new look in the village. The maps tended to draw the forthcoming railway line in pencil.

Arrangements in Box

The 1836 Tithe Commutation Act authorised parish meetings to determine voluntary rental payments in place of payments in kind. In December 1837, local impropriators called two meetings. For Box, Edward Richard Northey, William Brook Northey and John Fuller called a parochial meeting for 1 January 1838 at the Bear Inn for the purpose of making an agreement for the general commutation of tithes within the limits of the parish. For Ditteridge William Brook Northey called a similar meeting.[2] The Northey tenantry had earlier been softened up with a sumptuous dinner at the Bear that September.[3] It wasn't successful and in the event the meeting didn't give due notice and Northey's agent, Henry John Mant, solicitor, insisted that a deferred meeting needed to be held on 25 January.[4]

Some of Box's tithes had long since been commuted to a fixed price. Sometimes this happened when farm improvements or enclosure of common land had been made. In Box, enclosure often encouraged dairy farming and this tithe had been commuted to 3d per dairy cow. The tithe from Pinchin's and Drewett's mills had been commuted to 5 shillings annually. For other items, the apportionment sought to agree a rentcharge in lieu of traditional tithes. This was calculated as the amount of corn which could be grown on the land at the average 7-year price of corn nationally. It was meant to assist the landowner by defining the amount he was due to receive from tenants based on the value of corn. But instead, the Corn Laws of 1846 opened the way to lower corn prices and for the landlord lower rentcharges. In 1936 tithe rentcharges were abolished.

Box's Tithe Records

The introductory description of the record summarises the apportionment decided:

The tithes were divided between the rector, who received the Great Tithes of corn, grain, hay and wood, and the vicar, who got the Lesser Tithes (the rest). After the dissolution of the monasteries, many rectorial tithes were acquired by laymen (usually called the impropriator). The repairing of the chancel of the church was a liability of the impropriator and usually paid out of the rectorial tithes. In Box the impropriators were mostly the Northey family, although the Fuller family had bought a small amount of the tithes. The vicar, Rev HDCS Horlock, took most of the rest of the tithes. He lived in some luxury at Box House, next to the church, built by his ancestors. The tithe system had become an obvious anachronism by the end of the Georgian period, not applied to manufacturing or mining enterprises, resented by non-conformists, and it hurt farmers in the depression of the 1830s.

The abandonment of the system was a long and complicated national project, which took four years to achieve. Maps were drawn and re-drawn and three copies of the final award were made, for the parish, diocese and the Tithe Commission. As all this was happening, people died, land was divided and the railways and new roads came through Box splitting fields and creating a new look in the village. The maps tended to draw the forthcoming railway line in pencil.

Arrangements in Box

The 1836 Tithe Commutation Act authorised parish meetings to determine voluntary rental payments in place of payments in kind. In December 1837, local impropriators called two meetings. For Box, Edward Richard Northey, William Brook Northey and John Fuller called a parochial meeting for 1 January 1838 at the Bear Inn for the purpose of making an agreement for the general commutation of tithes within the limits of the parish. For Ditteridge William Brook Northey called a similar meeting.[2] The Northey tenantry had earlier been softened up with a sumptuous dinner at the Bear that September.[3] It wasn't successful and in the event the meeting didn't give due notice and Northey's agent, Henry John Mant, solicitor, insisted that a deferred meeting needed to be held on 25 January.[4]

Some of Box's tithes had long since been commuted to a fixed price. Sometimes this happened when farm improvements or enclosure of common land had been made. In Box, enclosure often encouraged dairy farming and this tithe had been commuted to 3d per dairy cow. The tithe from Pinchin's and Drewett's mills had been commuted to 5 shillings annually. For other items, the apportionment sought to agree a rentcharge in lieu of traditional tithes. This was calculated as the amount of corn which could be grown on the land at the average 7-year price of corn nationally. It was meant to assist the landowner by defining the amount he was due to receive from tenants based on the value of corn. But instead, the Corn Laws of 1846 opened the way to lower corn prices and for the landlord lower rentcharges. In 1936 tithe rentcharges were abolished.

Box's Tithe Records

The introductory description of the record summarises the apportionment decided:

- William Brook Northey £481.16s.4d for the Great Tithes as rector

- Rev HDCS Horlock £380 for the Lesser Tithes as vicar

- Rev HDCS Horlock £28.3s.8d for the glebe lands which had been commuted (agreed by the rector to support the vicar)

- Rev Henry Brereton £10 as rector of Hazelbury in lieu of a commuted amount

- John Fuller £8.10s for the Great Tithes as rector of 34 acres.

The Box records follow the standard form, listing the landowner, the occupier, map reference number, acreage, description, cultivation of each area and rentcharge assessed (not the charge payable but the par value which varied according to the corn price).

The Tithe apportionment records are often called the modern Domesday Record, the most detailed record of houses and plots of land ever undertaken which often formed the basis of later legal records. More than that, it was the symbolic end of an entirely rural economy and, indeed, the end of the Georgian period. In some ways it was the start of a modern period based on shops, businesses and quarries and the emergence of the worth of domestic houses. In some ways the maps produced were the precursor to the Ordnance Survey maps of England. Although the Ordnance Survey had been set up in 1791, its mapping endeavours in England at this time were focussed upon the First series maps at 1 inch to the mile, a task only completed in 1870.

The Tithe apportionment records are often called the modern Domesday Record, the most detailed record of houses and plots of land ever undertaken which often formed the basis of later legal records. More than that, it was the symbolic end of an entirely rural economy and, indeed, the end of the Georgian period. In some ways it was the start of a modern period based on shops, businesses and quarries and the emergence of the worth of domestic houses. In some ways the maps produced were the precursor to the Ordnance Survey maps of England. Although the Ordnance Survey had been set up in 1791, its mapping endeavours in England at this time were focussed upon the First series maps at 1 inch to the mile, a task only completed in 1870.

Need for Accurate Boundary Maps

Lieutenant RK Dawson of the Royal Engineers was seconded to the Tithe Commission in 1836 and produced a specification for the standard of mapping required. Dawson saw that there was an opportunity to produce a full set of cadastral maps (maps showing accurate property boundaries) for the entire country, similar to those being produced in a number of other European countries. The maps were administratively useful for resolution of boundary disputes and for planning new roads, canals and railways. In order to be able to show each individual land parcel accurately, Dawson specified a scale of three chains to the inch (26.7 inches to the mile, a scale similar to that of the later Ordnance Survey 25 inch maps).

Triangulation construction lines were to be left on the maps to provide a check on accuracy and these are visible on one copy of the Box tithe map.[5] By 1837 it became evident that many of the maps produced were inaccurate, and the insistence on such strict standards was an additional cost upon landowners. The Tithe commissioners appealed to the Chancellor of the Exchequer to defray the expenses of accurate cadastral survey from the public purse, as they could see that sooner or later there would be a need for accurate and uniform mapping of the entire country. A Select Committee was set up, but reached the view that, for the immediate purpose of Tithe commutation and apportionment, an accurate map was not strictly necessary. Furthermore it would be onerous to demand accurate maps for areas that were tithe-free, or where recent parochial or estate maps had been produced for other purposes. The result was an amendment of the Tithe Commutation Act to allow the Tithe Commissioners to accept maps at a variety of scales. Expediency and lobbying had put paid to a national cadastral survey and it would be several decades before a uniform series of maps at a detailed scale were available for the entire country

Lieutenant RK Dawson of the Royal Engineers was seconded to the Tithe Commission in 1836 and produced a specification for the standard of mapping required. Dawson saw that there was an opportunity to produce a full set of cadastral maps (maps showing accurate property boundaries) for the entire country, similar to those being produced in a number of other European countries. The maps were administratively useful for resolution of boundary disputes and for planning new roads, canals and railways. In order to be able to show each individual land parcel accurately, Dawson specified a scale of three chains to the inch (26.7 inches to the mile, a scale similar to that of the later Ordnance Survey 25 inch maps).

Triangulation construction lines were to be left on the maps to provide a check on accuracy and these are visible on one copy of the Box tithe map.[5] By 1837 it became evident that many of the maps produced were inaccurate, and the insistence on such strict standards was an additional cost upon landowners. The Tithe commissioners appealed to the Chancellor of the Exchequer to defray the expenses of accurate cadastral survey from the public purse, as they could see that sooner or later there would be a need for accurate and uniform mapping of the entire country. A Select Committee was set up, but reached the view that, for the immediate purpose of Tithe commutation and apportionment, an accurate map was not strictly necessary. Furthermore it would be onerous to demand accurate maps for areas that were tithe-free, or where recent parochial or estate maps had been produced for other purposes. The result was an amendment of the Tithe Commutation Act to allow the Tithe Commissioners to accept maps at a variety of scales. Expediency and lobbying had put paid to a national cadastral survey and it would be several decades before a uniform series of maps at a detailed scale were available for the entire country

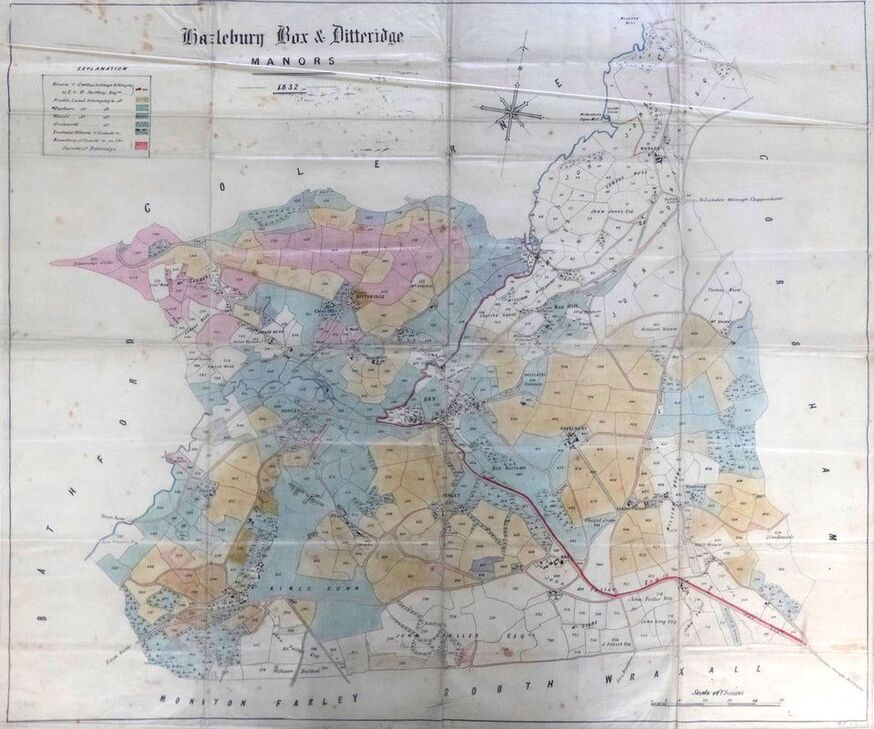

Northey Map of Box, 1832

The Northeys had commissioned a map of their holdings in Box only a few years previously in 1832.[6] The family underwent a considerable change of ownership in 1826 when the so-called Wicked Billy Northey died heirless. He had frequently stayed at Hazelbury Manor and on his death the estate passed back to the family line in Epsom, Surrey. The natural heir, Rev Edward Northey of Woodcote, forewent his position and his two sons, Colonel Edward Richard and William Brook Northey inherited, aged 31 and 21 respectively. The 1832 map was presumably an attempt to get to grips with their inheritance.

The Northey surveyor is not identified and the cartographic style clearly differs from that of the Tithe maps. It shows the Northey houses, differentiated from freehold houses, and individual fields owned by the Northeys coloured according to whether they were arable, pasture, woodland or orchards. Lands not owned by the Northeys are identified by owner, but the land-use for these is not shown. The scale is 10 chains to the inch (1:7920), so the map scale would have been inadequate for a first-class map and falls short of the accepted limit for second class maps of four chains to the inch.[7] The individual land parcels on the 1832 map are numbered, and the numbers correspond for the most part with those of the Tithe survey. It is thus highly likely that the data for the 1832 plan was used to compile the Tithe apportionment.

The Northeys had commissioned a map of their holdings in Box only a few years previously in 1832.[6] The family underwent a considerable change of ownership in 1826 when the so-called Wicked Billy Northey died heirless. He had frequently stayed at Hazelbury Manor and on his death the estate passed back to the family line in Epsom, Surrey. The natural heir, Rev Edward Northey of Woodcote, forewent his position and his two sons, Colonel Edward Richard and William Brook Northey inherited, aged 31 and 21 respectively. The 1832 map was presumably an attempt to get to grips with their inheritance.

The Northey surveyor is not identified and the cartographic style clearly differs from that of the Tithe maps. It shows the Northey houses, differentiated from freehold houses, and individual fields owned by the Northeys coloured according to whether they were arable, pasture, woodland or orchards. Lands not owned by the Northeys are identified by owner, but the land-use for these is not shown. The scale is 10 chains to the inch (1:7920), so the map scale would have been inadequate for a first-class map and falls short of the accepted limit for second class maps of four chains to the inch.[7] The individual land parcels on the 1832 map are numbered, and the numbers correspond for the most part with those of the Tithe survey. It is thus highly likely that the data for the 1832 plan was used to compile the Tithe apportionment.

Box and Ditteridge Tithe Maps

The tithe maps had to be specially prepared and the landowner had to pay for them. About 12% were called first-class maps (accepted as accurate). This figure fell to about 6% for Wiltshire, suggesting either local maps were made by less-skilled land surveyors or were derived in part from compilations of earlier maps rather than new surveys.[8] In the majority of cases three copies of each map and the award were made, one for the parish, one for the diocese and one for the Tithe Commission. The award provided details of landowners and occupiers within each tithe district usually based on the parish boundary.

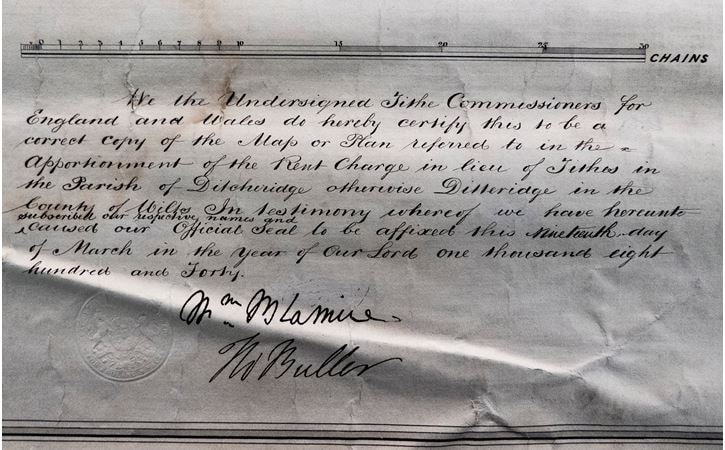

Both Box and Ditteridge were first class maps.[9] They were prepared by Cottrells and Cooper of Bath, who were responsible for 24 Tithe maps altogether: two in Gloucestershire, nineteen in Somerset and three in Wiltshire, the third Wiltshire map being that for Westbury which is also first class. Only first-class maps had seals: that on the Ditteridge map is shown below.

The tithe maps had to be specially prepared and the landowner had to pay for them. About 12% were called first-class maps (accepted as accurate). This figure fell to about 6% for Wiltshire, suggesting either local maps were made by less-skilled land surveyors or were derived in part from compilations of earlier maps rather than new surveys.[8] In the majority of cases three copies of each map and the award were made, one for the parish, one for the diocese and one for the Tithe Commission. The award provided details of landowners and occupiers within each tithe district usually based on the parish boundary.

Both Box and Ditteridge were first class maps.[9] They were prepared by Cottrells and Cooper of Bath, who were responsible for 24 Tithe maps altogether: two in Gloucestershire, nineteen in Somerset and three in Wiltshire, the third Wiltshire map being that for Westbury which is also first class. Only first-class maps had seals: that on the Ditteridge map is shown below.

Seal on the Ditteridge Tithe Map (WRO D/1/25/T/A/Ditteridge). The signatories are William Blamire, the Chairman of the Tithe Commissioners, and Captain Thomas Wentworth Buller, one of the other commissioners. The map is also signed by Robert Page, one of the assistant tithe commissioners and who was particularly concerned with reviewing the tithe agreements in Somerset.

The Box map, unusually for a first-class map, includes a miniature map of the world incorporated in the underlining of the map title.[10] Because the area of Box had become mixed with some tithes in Box area payable to Ditteridge parish and vice versa it was important to define the ancient boundary between the two parishes. For example, Prospect was in Ditteridge parish and Cheney Court in Box parish. The Tithe Acts 1839 and 1840 specified that an additional plan of the area should be made to enable the Tithe Commissioners to see where the two areas ran.

It isn't clear how the map shown above relates to the tithe map or when it was produced, but the pre-Great Western Railway configuration of field boundaries and the fact the railway is only visible as a very faint later addition indicate that it is probably of broadly similar date to the 1832 Northey estate map and the Tithe plan. Although it is similar to the Tithe maps in many respects, it is not as carefully drawn and in a few places actually differs from them. Ditteridge lands are shown in a light green colour to differentiate them from those of Box which surround them.

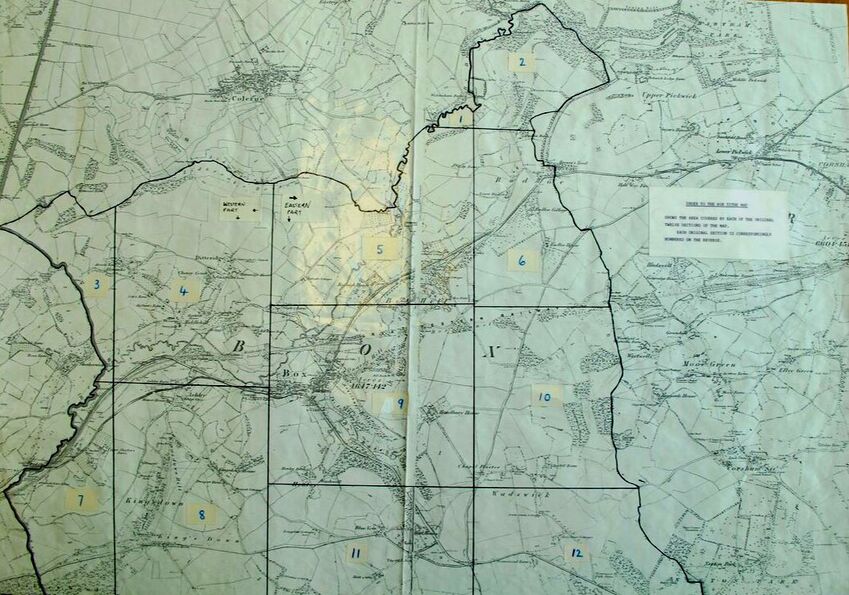

At a scale of 1:2376 the maps were large and unwieldy. That for Ditteridge is a single sheet over nine feet wide. The Box map was in two sheets (east and west), but even at this size the maps were awkward to use. The copy in the History Centre shows considerable signs of wear around the edges, and at some point the decision was taken to cut it into a number of smaller sheets. The relationship between the various sheets created by this action is indicated on an index sheet, which is a copy of the first edition OS 6” map of 1889, and also shows the development and changes which had taken place over some fifty years.

At a scale of 1:2376 the maps were large and unwieldy. That for Ditteridge is a single sheet over nine feet wide. The Box map was in two sheets (east and west), but even at this size the maps were awkward to use. The copy in the History Centre shows considerable signs of wear around the edges, and at some point the decision was taken to cut it into a number of smaller sheets. The relationship between the various sheets created by this action is indicated on an index sheet, which is a copy of the first edition OS 6” map of 1889, and also shows the development and changes which had taken place over some fifty years.

Places of Interest

The apportionment returns reveal some fascinating snippets of information, not otherwise recorded about the village. The Corsham and Lacock Road Commissioners had several tollhouses in the village including the Box Turnpike House (ref 361a), adjacent to the site of the present Post Office. The Parish House was listed in the back room of the Queen's Head (ref 187a).

The value of the plots for tithe purposes was totally different to our modern thinking. Cottages and houses had little or no value because they lacked sufficient land to be within the old system of assessment. In contrast, fishing in the ByBrook was a useful source of food and a Half-brook was meticulously measured; similarly, the willow withy beds on the brook north of Saltbox Farm, a valuable resource for making baskets and containers before plastic and aluminium (ref 66). They were presumably used by William Davies, basket-maker, who lived on Box Hill (ref 385b).

The malthouse for Box Brewery was run by a separate partnership called Pinchin, Simms & Company, further proof of the existence of Box Brewery two decades before the closure of the Bath Northgate Brewery in 1867. There are several shops listed in the village, the main ones being pubs, including Peter Smith at the New Inn (ref 334) which was the 1841 name of the Lamb Inn. A slaughterhouse and shop (ref 341a) was run by John Harding at the foot of what is now The Parade. Throughout the survey there were glimpses of Box's past. There were two hop gardens (refs 582 and 457), probably reflecting domestic beer brewing. A field along the approach to Hazelbury was called The Drove (ref 476), Swin(e) Leaze (ref 420) refers to ancient pannage rights and two fields were called Coney (meaning rabbit breeding area, at one time enclosed). The survey also included new items at that time: The Avenue at the Railway Station and Bassetts, after which new housing was later named.

Not all the lands in Ditteridge parish were owned by the Northey family. The gardens of Cuttings Mill (ref 210a and 210b) had already been sold to Thomas Andrews and John Fuller, Esq, held one field (ref 736). Edward Richard Northey and William Brook Northey held most of the land and, interestingly, they appear to have held all the Ditteridge parish land outside the hamlet, including Wormcliffe, Kingsdown and Kingsdown Wood.

The apportionment returns reveal some fascinating snippets of information, not otherwise recorded about the village. The Corsham and Lacock Road Commissioners had several tollhouses in the village including the Box Turnpike House (ref 361a), adjacent to the site of the present Post Office. The Parish House was listed in the back room of the Queen's Head (ref 187a).

The value of the plots for tithe purposes was totally different to our modern thinking. Cottages and houses had little or no value because they lacked sufficient land to be within the old system of assessment. In contrast, fishing in the ByBrook was a useful source of food and a Half-brook was meticulously measured; similarly, the willow withy beds on the brook north of Saltbox Farm, a valuable resource for making baskets and containers before plastic and aluminium (ref 66). They were presumably used by William Davies, basket-maker, who lived on Box Hill (ref 385b).

The malthouse for Box Brewery was run by a separate partnership called Pinchin, Simms & Company, further proof of the existence of Box Brewery two decades before the closure of the Bath Northgate Brewery in 1867. There are several shops listed in the village, the main ones being pubs, including Peter Smith at the New Inn (ref 334) which was the 1841 name of the Lamb Inn. A slaughterhouse and shop (ref 341a) was run by John Harding at the foot of what is now The Parade. Throughout the survey there were glimpses of Box's past. There were two hop gardens (refs 582 and 457), probably reflecting domestic beer brewing. A field along the approach to Hazelbury was called The Drove (ref 476), Swin(e) Leaze (ref 420) refers to ancient pannage rights and two fields were called Coney (meaning rabbit breeding area, at one time enclosed). The survey also included new items at that time: The Avenue at the Railway Station and Bassetts, after which new housing was later named.

Not all the lands in Ditteridge parish were owned by the Northey family. The gardens of Cuttings Mill (ref 210a and 210b) had already been sold to Thomas Andrews and John Fuller, Esq, held one field (ref 736). Edward Richard Northey and William Brook Northey held most of the land and, interestingly, they appear to have held all the Ditteridge parish land outside the hamlet, including Wormcliffe, Kingsdown and Kingsdown Wood.

Conclusion

The Tithe commutation was a late stage in a process which had already been under way for some time when the Allens produced their maps in the early 1600s. The Allen maps show clearly the piecemeal enclosure of the common fields. The overall trajectories of economic development and agrarian management varied according to locality, but as feudalism withered, so monetary values came to be applied to specific parcels of land. Previously income from land had not been based on calculations of land by area, except in the broadest of terms, so much as the package of rights over particular tracts of land according to manorial custom, those rights including the obligations of the tenants, often initially as labour service but increasingly as cash payments. The industrial revolution provided new uses for land (factories, mines, transport networks), many of which provided a far greater revenue per unit area than agriculture.

The Tithe commutation was a late stage in a process which had already been under way for some time when the Allens produced their maps in the early 1600s. The Allen maps show clearly the piecemeal enclosure of the common fields. The overall trajectories of economic development and agrarian management varied according to locality, but as feudalism withered, so monetary values came to be applied to specific parcels of land. Previously income from land had not been based on calculations of land by area, except in the broadest of terms, so much as the package of rights over particular tracts of land according to manorial custom, those rights including the obligations of the tenants, often initially as labour service but increasingly as cash payments. The industrial revolution provided new uses for land (factories, mines, transport networks), many of which provided a far greater revenue per unit area than agriculture.

References

[1] A copy of the Tithe plan is available at the Wiltshire History Centre (ref: D/1/25/T/A/Box). Another, on which the surveyor’s construction lines are visible, can be viewed online at Know your Place (http://maps.bristol.gov.uk/kyp/?edition=wilts) where it can be overlaid upon various historic and current maps – a useful resource. To access, go to the website, Basemaps, click the arrows top right and 1840s Wiltshire Tithes.

[2] The Wiltshire Independent, 21 December 1837

[3] The Wiltshire Independent, 28 September 1837

[4] The Wiltshire Independent, 11 January 1838

[5] Reproduced on the Know Your Place website

[6] Map of Hazlebury, Box and Ditteridge manors, Wiltshire History Centre, WRO 1265/3

[7] Kain RJP and Prince HC, 2000, Tithe Surveys for Historians (Phillimore, Chichester), p38

[8] RJP Kain and RR Oliver, The Tithe Maps of England and Wales: a cartographic analysis and county-by-county catalogue, 1995, Cambridge University Press, p.708-14

[9] RJP Kain and RR Oliver, The Tithe Maps of England and Wales, 38/34 and 38/99

[10] This is on the National Archives copy and illustrated in RJP Kain and RR Oliver, The Tithe Maps of England and Wales, figure 158, p.806

[1] A copy of the Tithe plan is available at the Wiltshire History Centre (ref: D/1/25/T/A/Box). Another, on which the surveyor’s construction lines are visible, can be viewed online at Know your Place (http://maps.bristol.gov.uk/kyp/?edition=wilts) where it can be overlaid upon various historic and current maps – a useful resource. To access, go to the website, Basemaps, click the arrows top right and 1840s Wiltshire Tithes.

[2] The Wiltshire Independent, 21 December 1837

[3] The Wiltshire Independent, 28 September 1837

[4] The Wiltshire Independent, 11 January 1838

[5] Reproduced on the Know Your Place website

[6] Map of Hazlebury, Box and Ditteridge manors, Wiltshire History Centre, WRO 1265/3

[7] Kain RJP and Prince HC, 2000, Tithe Surveys for Historians (Phillimore, Chichester), p38

[8] RJP Kain and RR Oliver, The Tithe Maps of England and Wales: a cartographic analysis and county-by-county catalogue, 1995, Cambridge University Press, p.708-14

[9] RJP Kain and RR Oliver, The Tithe Maps of England and Wales, 38/34 and 38/99

[10] This is on the National Archives copy and illustrated in RJP Kain and RR Oliver, The Tithe Maps of England and Wales, figure 158, p.806