Mullins Family, Schoolmasters of Box Patrick Mullins Written in 1991

Patrick Mullins died in 1996, having spent 25 years researching his remarkable family story. We publish this article, with the kind permission of his son, Peter Mullins.

For some years I have gradually been acquiring information about my Mullins ancestors. There is much still to be unearthed and a lot of checking to be done because a good deal of the material passed on to me should not be accepted uncritically. The Mullins family lived at Box in Wiltshire for over two centuries. For much of that time they were closely involved in the affairs of Box church and of a local school.

Henry, George and Edward Mullins, 1630 – 1746

There is in existence a copy of a typewritten family tree tracing the family back to Sir Reginald de Moleyns, Knight, in 1272, and on the distaff side to the descendants of Edward I. I know nothing of the provenance of this document or of the sources of its information. The Mullins family, when first reliably encountered, were much humbler folk than this alleged background would suggest.

The first name to emerge from the mists of speculation is a Henry Mullins, variously described by older relatives of mine as having been born at Box in 1630 and as having come from Ireland and settled in Wiltshire. Again, I know of no evidence for that later statement, although Mullinses are legion in Ireland. There is also a remote possibility that before Henry’s time the family lived in Bristol. We do not know Henry’s parentage or anything firm about him other than that he was buried at Colerne on 10 September 1675 and that he had a son, George, baptised on 19 December 1667 also at Colerne. Henry Mullins appears to have lived locally all his life and his son described himself as yeoman which was probably his father’s social level.

I believe that the George Mullins buried at Box on 10 December 1733 was in fact Henry’s son. His age is given on his tombstone as 66, which takes us back to 1667 and squares with the baptism date given above. Another George, buried at Colerne in 1728, may have been a son of Henry. Certainly there was a clan of Mullinses in the area in the early years of the eighteenth century and the families were depressingly unoriginal in their choice of first names.

It is with that son, George (1667 – 1733) that we come at last to solid ground. He was twice married. His first wife, Suzannah Lewis, bore him Edward and Hannah and, after her death, he married Elizabeth, by whom he had three daughters, Suzannah, Elizabeth and Elinor. That information comes from his will dated 20 November 1773, immediately before his death. He made his mark on the document rather than signing his name but that was probably due to debility rather than illiteracy. George made specific bequests totalling £111 to members of his family together with all household goods and implements and cattle, sheep, corn, hay etc. For that period, he seems to have been comfortably placed in material terms. There is no evidence that he was in any way involved in the new school.

His son Edward (1703 – 1746) adds a touch of colour to the story. He was married on 10 December 1727 to Lydia Lovel, reputedly the daughter of an ancient baronial family and thus several steps up the social scale. Unsurprisingly, it was said to be a runaway marriage. It took place at Norton St Philip, about five miles south of Bath, and both bride and groom were described as being of Farleigh Hungerford, the next village to the east of Norton St Philip. There is a mild curiosity here because Farleigh Hungerford was where Lord Moleyns, a rough, old soldier from the Hundred Years War, had lived. He featured prominently in the Paston Letters as one of their principal antagonists and carried his bellicosity into the Wars of the Roses, picking the wrong side (the Red Rose) and being executed in 1464, his peerage becoming extinct when his son was also executed. Anyway, if Edward and Lydia ran away, they soon came back to Box. The baptisms of six of their children are recorded in the Box registers in the years 1728 to 1740. The eldest son was another George, baptised on 7 December 1728.

Edward and Lydia, with three of their children, all died at Box in the spring of 1746. The most likely cause of the disaster was smallpox, which was endemic in the area over several generations. Edward was described in the burial register as clerk. He may have lived at Slades Farm, adjoining the school’s twenty-acre plot, and was a tenant farmer like his father.[1] He may also have been the first of the Mullins schoolmasters. His son George was said, at his death in 1796, to have been a schoolmaster for fifty years. Taking that statement quite literally, he would have assumed the job in 1746 at the age of seventeen. It seems much more likely that he stepped into his father’s shoes than that he was independently chosen for the role at such an early age. By 1746 the school had been in existence for thirty years or more and was well established.

There is in existence a copy of a typewritten family tree tracing the family back to Sir Reginald de Moleyns, Knight, in 1272, and on the distaff side to the descendants of Edward I. I know nothing of the provenance of this document or of the sources of its information. The Mullins family, when first reliably encountered, were much humbler folk than this alleged background would suggest.

The first name to emerge from the mists of speculation is a Henry Mullins, variously described by older relatives of mine as having been born at Box in 1630 and as having come from Ireland and settled in Wiltshire. Again, I know of no evidence for that later statement, although Mullinses are legion in Ireland. There is also a remote possibility that before Henry’s time the family lived in Bristol. We do not know Henry’s parentage or anything firm about him other than that he was buried at Colerne on 10 September 1675 and that he had a son, George, baptised on 19 December 1667 also at Colerne. Henry Mullins appears to have lived locally all his life and his son described himself as yeoman which was probably his father’s social level.

I believe that the George Mullins buried at Box on 10 December 1733 was in fact Henry’s son. His age is given on his tombstone as 66, which takes us back to 1667 and squares with the baptism date given above. Another George, buried at Colerne in 1728, may have been a son of Henry. Certainly there was a clan of Mullinses in the area in the early years of the eighteenth century and the families were depressingly unoriginal in their choice of first names.

It is with that son, George (1667 – 1733) that we come at last to solid ground. He was twice married. His first wife, Suzannah Lewis, bore him Edward and Hannah and, after her death, he married Elizabeth, by whom he had three daughters, Suzannah, Elizabeth and Elinor. That information comes from his will dated 20 November 1773, immediately before his death. He made his mark on the document rather than signing his name but that was probably due to debility rather than illiteracy. George made specific bequests totalling £111 to members of his family together with all household goods and implements and cattle, sheep, corn, hay etc. For that period, he seems to have been comfortably placed in material terms. There is no evidence that he was in any way involved in the new school.

His son Edward (1703 – 1746) adds a touch of colour to the story. He was married on 10 December 1727 to Lydia Lovel, reputedly the daughter of an ancient baronial family and thus several steps up the social scale. Unsurprisingly, it was said to be a runaway marriage. It took place at Norton St Philip, about five miles south of Bath, and both bride and groom were described as being of Farleigh Hungerford, the next village to the east of Norton St Philip. There is a mild curiosity here because Farleigh Hungerford was where Lord Moleyns, a rough, old soldier from the Hundred Years War, had lived. He featured prominently in the Paston Letters as one of their principal antagonists and carried his bellicosity into the Wars of the Roses, picking the wrong side (the Red Rose) and being executed in 1464, his peerage becoming extinct when his son was also executed. Anyway, if Edward and Lydia ran away, they soon came back to Box. The baptisms of six of their children are recorded in the Box registers in the years 1728 to 1740. The eldest son was another George, baptised on 7 December 1728.

Edward and Lydia, with three of their children, all died at Box in the spring of 1746. The most likely cause of the disaster was smallpox, which was endemic in the area over several generations. Edward was described in the burial register as clerk. He may have lived at Slades Farm, adjoining the school’s twenty-acre plot, and was a tenant farmer like his father.[1] He may also have been the first of the Mullins schoolmasters. His son George was said, at his death in 1796, to have been a schoolmaster for fifty years. Taking that statement quite literally, he would have assumed the job in 1746 at the age of seventeen. It seems much more likely that he stepped into his father’s shoes than that he was independently chosen for the role at such an early age. By 1746 the school had been in existence for thirty years or more and was well established.

George Mullins 1728 – 1796

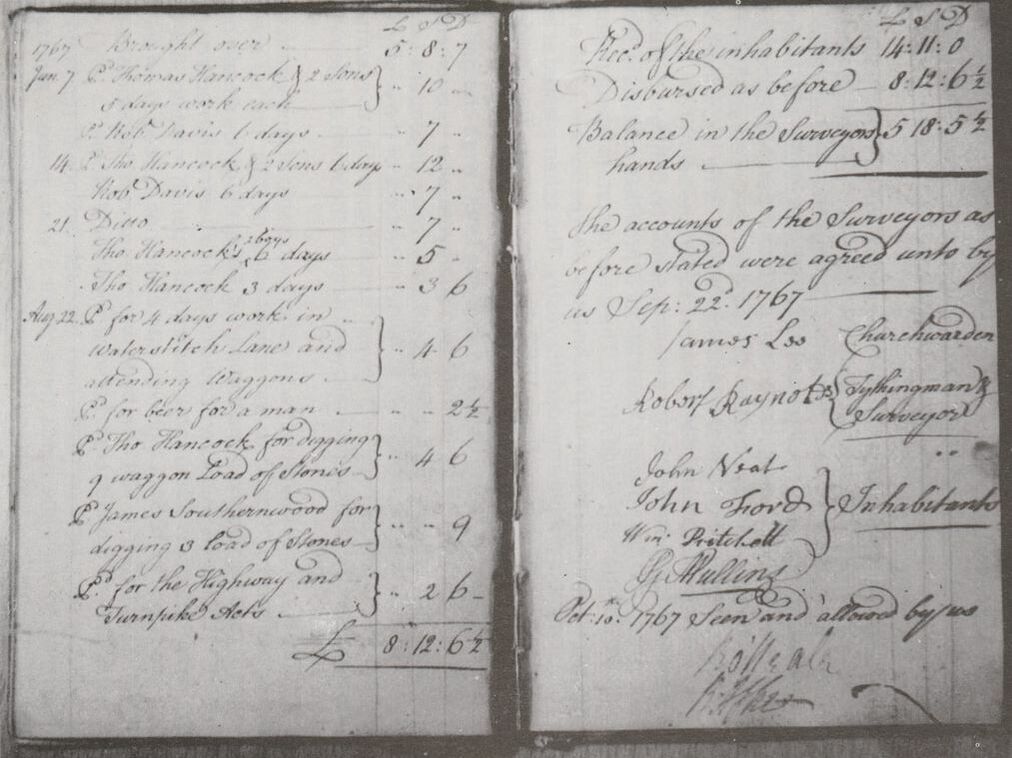

The life of this George, son of Edward, firmly establishes a pattern that was to continue for almost a century – a close connection with Box Church and with the charity school. He was churchwarden in 1760-01 and in 1778 was one of the signatories of the vestry minutes (as an inhabitant) from 1772 onwards. He, or his son of the same name, was vestry clerk in 1787. He may have been parish clerk, as his son certainly was, but the records do not always differentiate between George Mullins senior and junior when their careers overlap. One exception, as late as 1793, identifies George senior as a signatory of the overseers’ minutes. One of them, father or son, was churchwarden in 1786 and 1788 and, as the son was still in his twenties at that stage, it was probably the father. Anyhow, he was a literate and active member of the village community. His signature, again as inhabitant, is seen in the 1767 Highway Accounts.[2]

The life of this George, son of Edward, firmly establishes a pattern that was to continue for almost a century – a close connection with Box Church and with the charity school. He was churchwarden in 1760-01 and in 1778 was one of the signatories of the vestry minutes (as an inhabitant) from 1772 onwards. He, or his son of the same name, was vestry clerk in 1787. He may have been parish clerk, as his son certainly was, but the records do not always differentiate between George Mullins senior and junior when their careers overlap. One exception, as late as 1793, identifies George senior as a signatory of the overseers’ minutes. One of them, father or son, was churchwarden in 1786 and 1788 and, as the son was still in his twenties at that stage, it was probably the father. Anyhow, he was a literate and active member of the village community. His signature, again as inhabitant, is seen in the 1767 Highway Accounts.[2]

|

As we have seen, the school was a charity one, established in the early years of the eighteenth century. In 1719, one of the Speke family gave land adjoining Box Church on which was built a house of seven rooms, for use as a master’s house and school. Soon afterwards a parish workhouse was built and its two top stories were given over to a school. The youthful George was schoolmaster from the late 1740s, as his father Edward may earlier have been.

It was this George who decided to branch out and take in paying pupils. He built a staircase for this purpose from the ground direct to the top floor of the workhouse, connecting the new schoolroom with his own garden. The Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine says to the number of thirty children who are parishioners of Box … the present schoolmaster has added about ten pay scholars … Pay scholars and free scholars are seldom classed together when taught but religious instruction is given alike. Charity School on top floor of Box Workhouse (courtesy Carol Payne) |

The pay scholars rapidly became a family business and quite a profitable one. Several public advertisements for them have come to light and you can see growing confidence. The first from the Bath Chronicle possibly in 1755 reads:

Youths boarded and taught reading, writing, arithmetic, bookkeeping, mensuration etc and all things requisite in trade and business by George Mullins at Box in the County of Wiltshire. Those who care to favour me with the care of their children may depend on their being well boarded and expeditiously qualified for business.

Clearly at that stage he was referring to boys only.

However, by 1783 we get:

At Mullins’ Boarding school at Box in the county of Wiltshire. The Terms are:

For Boys’ Board and instruction in reading, writing of all useful hands, arithmetic in all its parts, bookkeeping after the modern and Italian methods, geometry, mensuration of superficies and solids, gauging, surveying, dialling use of the globes etc: A guinea entrance and twelve guineas a year

For Girls’ Board and instruction in reading, writing, bookkeeping and the various kinds of plain and ornamental needlework: A guinea entrance and twelve guineas a year.

Latin and French, entrance (crossed out) shillings and (crossed out) shillings a quarter.

Dancing, entrance half a guinea and 12s.6d a quarter.

Music, entrance half a guinea and one guinea a quarter.

Drawing if required.

The utmost care and attention will be paid to the health and morals of the pupils of both sexes and no pains spared to instruct them in the several parts of learning, according to their respective capacities and dispositions.

At the same time, there is a bill to Mr Vine for a half year’s education for his sons John and Thomas. In addition to the standard charge for tuition, Mr Vine was charged 11s.5d for books and other stationery, 7s.4d for cash lent weekly, 3s.3d for the tailor, and 6s.4d for the shoemaker. There were four-week holidays at midsummer and at Christmas and pupils remaining at school for a vacation were charged one guinea extra.

Youths boarded and taught reading, writing, arithmetic, bookkeeping, mensuration etc and all things requisite in trade and business by George Mullins at Box in the County of Wiltshire. Those who care to favour me with the care of their children may depend on their being well boarded and expeditiously qualified for business.

Clearly at that stage he was referring to boys only.

However, by 1783 we get:

At Mullins’ Boarding school at Box in the county of Wiltshire. The Terms are:

For Boys’ Board and instruction in reading, writing of all useful hands, arithmetic in all its parts, bookkeeping after the modern and Italian methods, geometry, mensuration of superficies and solids, gauging, surveying, dialling use of the globes etc: A guinea entrance and twelve guineas a year

For Girls’ Board and instruction in reading, writing, bookkeeping and the various kinds of plain and ornamental needlework: A guinea entrance and twelve guineas a year.

Latin and French, entrance (crossed out) shillings and (crossed out) shillings a quarter.

Dancing, entrance half a guinea and 12s.6d a quarter.

Music, entrance half a guinea and one guinea a quarter.

Drawing if required.

The utmost care and attention will be paid to the health and morals of the pupils of both sexes and no pains spared to instruct them in the several parts of learning, according to their respective capacities and dispositions.

At the same time, there is a bill to Mr Vine for a half year’s education for his sons John and Thomas. In addition to the standard charge for tuition, Mr Vine was charged 11s.5d for books and other stationery, 7s.4d for cash lent weekly, 3s.3d for the tailor, and 6s.4d for the shoemaker. There were four-week holidays at midsummer and at Christmas and pupils remaining at school for a vacation were charged one guinea extra.

|

George became something of a man of property and John Ayers, recorded in Box Charity School: His parents were related to one of the powerful families of the district by the name of Neate.[3] In 1766 he acquired a mill and, in 1791, two houses and land in addition to the school lands.

In his 1795 will George left his interest in the school, on the boys’ side, to his sons, George and Edward, and, on the girls’ side, to his son John and his daughter Jane, all of whom appear to have been involved for some time in the running of what may have been a profitable family business. Perhaps as a result of these fees, George became, in a modest way, a man of property. In his will he disposed to members of his family my messuage and tenement wherein I now dwell and also the several other messuages and tenements … being at Box aforesaid . His daughter Jane received all that my messuage or tenement wherein she now lives and also the new erected messuage or tenement thereto adjoining, now used as a school for young ladies, with the gardens, outhouses, hereditaments and premises thereto belonging. Two of his sons shared all my musical books and instruments. One wonders how, and where, George himself was educated and learned his music. Left: Poorhouse and Springfield Cottages (Carol Payne) |

One of the properties of which he was part-owner was the house opposite the church, known at times as Church House and later The Wilderness. It is a large, rambling seventeenth-century house to which later additions were made and which was to become the albatross around the family’s neck, although not in this generation. The house had belonged to the Northey family. In 1729 Thomas Nutt bought The Wilderness from William Northey and, in his will of 1748, he left it to his three daughters, Elizabeth, Mary and Ann Nutt. In 1750 George Mullins married Mary Nutt. Elizabeth Nutt married Michael Naish. Ann Nutt apparently remained unmarried until she parted with her one-third share of the property to her brothers-in-law for £60, about which more later. Mullins, Naish and their wives shared the house, or at least the ownership of it, for many years. There were hints of underlying issues when in 1763 George Stephen took out a summons against George and Mary Mullins and the Naishes for alleged seizure or illegal possession of a property. The details are not clear and the outcome is unknown. In 1780 came the first actual sign of future trouble. A man called Stephen Bridges obtained a court settlement against Mullins, Naish and their respective wives which enforced the sale to him of a cottage and water grist mill, in the possession of the four, for £100.

In 1787 George leased a property known as Pantons at Middle Hill, consisting of three houses, gardens, orchards and pastures. In 1792, not surprisingly, he was listed among those who occupied property valued at £50 or more. The impression I have of George is of a conscientious, acquisitive man, who came to be regarded as of some standing locally. There was in existence a portrait of him but, sadly, on the death of an aunt of mine in 1951, it was given away. George and his wife had twelve children but only four survived into adult life, three sons and a daughter. Of those four, Jane did not marry. She had been established by her father in a separate house, possibly Townsend Villa in Box. Edward married twice but probably had no children. John died in 1807 leaving several sons who were brought up in the house of his eldest brother at The Wilderness.

George Mullins, 1759 – 1842

This lengthy life spans one of the most dramatic periods of change in English history. He was born in the reign of George II in a totally rural village, devoid of proper roads, where the pattern of life had changed only gradually over the centuries. He lived throughout the Industrial Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the coming of steamships and trains and for five years into the reign of Queen Victoria. All his life was spent in Box and he is the last male Mullins in the direct line to have died there.

As we have seen, he was closely connected with the church and with the school, at least on its money-making side. He seems to have lived all his life at The Wilderness, dying just before disaster finally struck. He was a churchwarden for at least thirteen of the first 26 years of the 1800s and vestry clerk for over thirty years. He was clearly a man of independent mind. As a vestry clerk he was supposed to keep a record of meetings but refused to do so until it was agreed to pay him separately for each meeting. In his later years he rejected a scheme to lock the poor of the village in the poorhouse. For at least eight years he was closely involved in a wrangle with the Bath Turnpike Trust over responsibility for a five-mile stretch of the road within the parish. As vestry clerk George had to provide for cleaning, repairs, heating and fire insurance of the poorhouse, for the clothing of inmates and for their medical care, and for the fostering of infants and young children. He kept the parish accounts for some years and was rewarded with 2s.6d for so doing in the years 1791-93, raised to 5s in 1794.

Like his father he seems to have been an acquisitive man and the school took up much of his time. An advertisement of 1814 displayed a confident approach. The pupils were now called the sons and daughters of gentlemen and tradesmen. The girls were taught in a separate house by Jane Mullins and assistants. The fees were now twenty guineas a year. In addition to The Wilderness which he shared with Michael Naish and their wives, George rented other property from Mr Northey. His wife paid 1s.6d rent on the school house and his sister Jane rented another house from her widowed sister-in-law Susanna Mullins.

Socially, George appears to have been a village worthy rather than a member of the gentry. His wife was a local woman, Mary Cornish, whom he married in 1791. But they lived in a big house with interests in other property. They achieved their golden wedding anniversary before his death in 1842 and Mary’s in 1844.

In his later years George became involved in litigation over the ownership of The Wilderness, a process which came to a disastrous end just after his death. Enter Mary Miller, about whom little is known, perhaps a relative of Ann Nutt or Stephen Bridges, already mentioned.

This lengthy life spans one of the most dramatic periods of change in English history. He was born in the reign of George II in a totally rural village, devoid of proper roads, where the pattern of life had changed only gradually over the centuries. He lived throughout the Industrial Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the coming of steamships and trains and for five years into the reign of Queen Victoria. All his life was spent in Box and he is the last male Mullins in the direct line to have died there.

As we have seen, he was closely connected with the church and with the school, at least on its money-making side. He seems to have lived all his life at The Wilderness, dying just before disaster finally struck. He was a churchwarden for at least thirteen of the first 26 years of the 1800s and vestry clerk for over thirty years. He was clearly a man of independent mind. As a vestry clerk he was supposed to keep a record of meetings but refused to do so until it was agreed to pay him separately for each meeting. In his later years he rejected a scheme to lock the poor of the village in the poorhouse. For at least eight years he was closely involved in a wrangle with the Bath Turnpike Trust over responsibility for a five-mile stretch of the road within the parish. As vestry clerk George had to provide for cleaning, repairs, heating and fire insurance of the poorhouse, for the clothing of inmates and for their medical care, and for the fostering of infants and young children. He kept the parish accounts for some years and was rewarded with 2s.6d for so doing in the years 1791-93, raised to 5s in 1794.

Like his father he seems to have been an acquisitive man and the school took up much of his time. An advertisement of 1814 displayed a confident approach. The pupils were now called the sons and daughters of gentlemen and tradesmen. The girls were taught in a separate house by Jane Mullins and assistants. The fees were now twenty guineas a year. In addition to The Wilderness which he shared with Michael Naish and their wives, George rented other property from Mr Northey. His wife paid 1s.6d rent on the school house and his sister Jane rented another house from her widowed sister-in-law Susanna Mullins.

Socially, George appears to have been a village worthy rather than a member of the gentry. His wife was a local woman, Mary Cornish, whom he married in 1791. But they lived in a big house with interests in other property. They achieved their golden wedding anniversary before his death in 1842 and Mary’s in 1844.

In his later years George became involved in litigation over the ownership of The Wilderness, a process which came to a disastrous end just after his death. Enter Mary Miller, about whom little is known, perhaps a relative of Ann Nutt or Stephen Bridges, already mentioned.

|

It seems that Ann Nutt’s one-third share in her father’s house may not have been properly purchased by the brothers-in-law. Various solutions were advocated in 1822: that Mary Miller should receive payments from George whereby he could continue to live in the house; that the property be mortgaged; and that George and his wife should be bound by the sum of £1,000 to honour the arrangements. In an 1831 document it becomes clear that the agreement with Mary Miller had not been honoured allowing her to use the house and outbuildings and receive a payment of £500. Interest and arrears had been paid to her but not the principal sum of £500. As a result, her entitlement to the property had now become absolute at law. George senior then chose this time to dispose of his share of the heavily-mortgaged and debt-ridden property to his parson son.

|

George died in 1842, immediately before the final outcome of The Wilderness saga and was buried in one of the family tombs in Box Churchyard which contain no fewer than twenty-three members of the Mullins and Nutt families.

|

Rev George Mullins 1800 – 1867 My father, who was born eleven years after George died, was led to believe that the Reverend George Mullins blewed the family money. However, that may have been rather unjust, in part at least, because The Wilderness was already in hock to Mary Miller by 1822, at a time when George had barely reached his majority. His ordination in 1823 was achieved on the say-so of local clergymen. Three of them – WL Bowles of Bremhill, JWW Horlock of Box and JL Willis of Ditcheridge – certified to the bishop of Salisbury that the young George, whose life and behaviour we have known for the space of three years now last past, is a person of good life and conversation. William Northey, the local squire, made it known that he would appoint George to the living at Ditteridge in the case of Mr Willis resigning the same. Willis then wrote to the bishop on 11 November 1823 nominating and appointing George as curate in my church of Ditcheridge at £40 pa. Eight months later, the youthful deacon was made a priest. Richard Warner, Rector of Great Chalfield, also wanted George as a curate and did, in fact, employ him from September 1824. The lucky young George finished up with two curacies, several miles apart, bringing him £40 and £50 pa respectively. He continued to live in Box. Rev George Mullins about 1855 (courtesy Peter Mullins) |

After four generations of village worthies, this George enjoyed a lifestyle different to his ancestors. He was better educated than his ancestors and had contact with some highly literate fellow clergymen. Despite the financial issues over The Wilderness, he sent at least two of his sons to public schools and the eldest one to Oxford in 1855. The 1841 census reveals a still united family living at Box. At Church House George Mullins, Clerk, Rector of Ditteridge, Susannah his wife, and four young children. Close by in Church Yard, were his father George Mullins, Schoolmaster, mother Mary, and sisters Mary Jane and Rachel, Governesses.

Why did Rev George leave Box? Principally because Mary Miller finally caught up with the family. By 1842 when his father died, the debt on the house amounted to £650 and she foreclosed on it. The house was put up for sale in June of that year but no buyer was found. In September a deed of sale was enforced on George, Mary Miller becoming the owner subject only to the undertaking that she should absolve him from any further payments or suits in law. It seems he left Box at once and went to live in Ditteridge, where he remained for four years before moving to the Warden’s House at Corsham Almshouse where he was Master of the house from about 1846.

For some years prior to his departure from Box, Rev George continued to take in fee-paying children at the school and advertised in the 1830s at fees of 40 or 50 guineas a year, double since 1814. But there was no specific mention of girls and the advertisement was rather more off-hand than previous ones. From 1825 he was Rector of Ditteridge and Curate of Great Chalfield and possibly helped out in Box Church, all of which provided an income. Between them they should have provided him with a good income, but not enough of one, it seems. It has to be said that Rev George was anything but a conscientious man. He interested himself closely in the discovery of the remains of the substantial Roman villa in the gardens of The Wilderness in 1831.

There is one letter that gives a brief, tantalising glimpse into Rev George’s private life. It was written to George from the Rev William Lisle Bowles, vicar of Bremhill probably written in the period 1831-33. It reads:

My dear Mullins

How shall I thank you for a fish so magnificent? Hoyle is here (Charles Hoyle, vicar of Overton, Marlborough) – but alas! goes tomorrow and cannot partake of it but the Doctor of Corsham dines tomorrow – Sylvanus Urban (John Nichols, editor of The Gentleman’s Magazine) – the Rev John Skinner of Camerton (near Radstock) and why not George Mullins of Box? Do please come and see such a trout cut up, a treat worthy of Tickler and the guests of Doctor Ambrosiana and old Isaac himself – take a slice of him and wash him down with a glass of Bremhill port! You will receive this at ten o’clock. Harness the horse and be here at five – you might sleep here if more convenient and believe me.

Ever & ce WL Bowles

It is a letter that might have been sent to a leisured man who is ready to accept an invitation at virtually no notice and who will think of nothing of riding ten or more miles to do so.

It is sad that this easy-going, civilised but perhaps improvident man should come to a rather anonymous end as a chronic invalid. George resigned the Almshouse August 1861 from declining health … went to Bath, had giddiness of the head and fits. He died in 1867 at Oxford. He and his wife are both supposed to have been buried there in Oxford but I cannot find out where.

Why did Rev George leave Box? Principally because Mary Miller finally caught up with the family. By 1842 when his father died, the debt on the house amounted to £650 and she foreclosed on it. The house was put up for sale in June of that year but no buyer was found. In September a deed of sale was enforced on George, Mary Miller becoming the owner subject only to the undertaking that she should absolve him from any further payments or suits in law. It seems he left Box at once and went to live in Ditteridge, where he remained for four years before moving to the Warden’s House at Corsham Almshouse where he was Master of the house from about 1846.

For some years prior to his departure from Box, Rev George continued to take in fee-paying children at the school and advertised in the 1830s at fees of 40 or 50 guineas a year, double since 1814. But there was no specific mention of girls and the advertisement was rather more off-hand than previous ones. From 1825 he was Rector of Ditteridge and Curate of Great Chalfield and possibly helped out in Box Church, all of which provided an income. Between them they should have provided him with a good income, but not enough of one, it seems. It has to be said that Rev George was anything but a conscientious man. He interested himself closely in the discovery of the remains of the substantial Roman villa in the gardens of The Wilderness in 1831.

There is one letter that gives a brief, tantalising glimpse into Rev George’s private life. It was written to George from the Rev William Lisle Bowles, vicar of Bremhill probably written in the period 1831-33. It reads:

My dear Mullins

How shall I thank you for a fish so magnificent? Hoyle is here (Charles Hoyle, vicar of Overton, Marlborough) – but alas! goes tomorrow and cannot partake of it but the Doctor of Corsham dines tomorrow – Sylvanus Urban (John Nichols, editor of The Gentleman’s Magazine) – the Rev John Skinner of Camerton (near Radstock) and why not George Mullins of Box? Do please come and see such a trout cut up, a treat worthy of Tickler and the guests of Doctor Ambrosiana and old Isaac himself – take a slice of him and wash him down with a glass of Bremhill port! You will receive this at ten o’clock. Harness the horse and be here at five – you might sleep here if more convenient and believe me.

Ever & ce WL Bowles

It is a letter that might have been sent to a leisured man who is ready to accept an invitation at virtually no notice and who will think of nothing of riding ten or more miles to do so.

It is sad that this easy-going, civilised but perhaps improvident man should come to a rather anonymous end as a chronic invalid. George resigned the Almshouse August 1861 from declining health … went to Bath, had giddiness of the head and fits. He died in 1867 at Oxford. He and his wife are both supposed to have been buried there in Oxford but I cannot find out where.

Family Tree

George Mullins (1667 – 1733) married 1. Suzannah Lewis and 2. Elizabeth. Children:

1. Edward (1703 – 1746); Hannah

2. Suzannah; Elizabeth; and Elinor

Edward Mullins (1703 – 1746) married Lydia Lovel. Children:

George Mullins (1728 – 1796);

George Mullins (1728 – 1796) married Mary Nutt (1727 – 1801). Children included:

Jane (1750 – 1816); George (1759 – 1842); Edward (1762 – 1813); and John (1764 – 1807).

George Mullins (1759 – 1842) married Mary Cornish (d 1844) in 1791. Children include:

Rev George (1800 – 1867)

Rev George Mullins (1800 – 1867) married Susannah Gardiner and had at least eight children.

George Mullins (1667 – 1733) married 1. Suzannah Lewis and 2. Elizabeth. Children:

1. Edward (1703 – 1746); Hannah

2. Suzannah; Elizabeth; and Elinor

Edward Mullins (1703 – 1746) married Lydia Lovel. Children:

George Mullins (1728 – 1796);

George Mullins (1728 – 1796) married Mary Nutt (1727 – 1801). Children included:

Jane (1750 – 1816); George (1759 – 1842); Edward (1762 – 1813); and John (1764 – 1807).

George Mullins (1759 – 1842) married Mary Cornish (d 1844) in 1791. Children include:

Rev George (1800 – 1867)

Rev George Mullins (1800 – 1867) married Susannah Gardiner and had at least eight children.

References

[1] John Ayers, A Christian and Useful Education, B Ed Dissertation Thesis, p.23

[2] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, 1985, The Dowland Press, p.100

[3] John Ayers, A Christian and Useful Education, B Ed Dissertation Thesis, p.23

[1] John Ayers, A Christian and Useful Education, B Ed Dissertation Thesis, p.23

[2] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, 1985, The Dowland Press, p.100

[3] John Ayers, A Christian and Useful Education, B Ed Dissertation Thesis, p.23