|

The Rev George Mullins, 1800 - 1867 Peter Mullins May 2016 Family photographs courtesy Peter Mullins George Mullins was born at the very end of the eighteenth century, on 17 August 1800, at Box where the Mullins family had lived for several generations. He was the last of a family line of Box schoolmasters which had begun with George's grandfather in 1746. The family had acquired substantial property in the village including Church House (now called The Wilderness) but it ended in poverty. This account had developed over many years based on a range of primary and secondary sources; readers in Box and Corsham in particular will spot the points at which some details come from John Ayer’s work on local education and from Ernest Hird’s work on the Hungerford Almshouses which are gratefully acknowledged. |

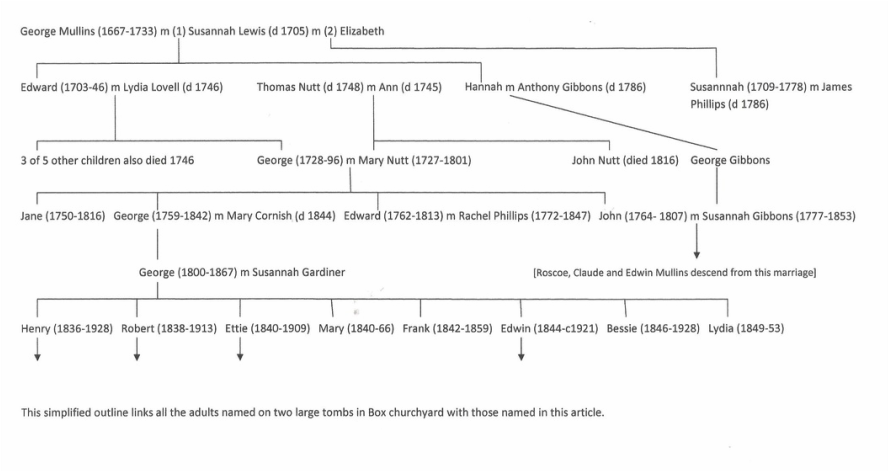

Mullins Family

His grandfather, a first George (1728-96), son and grandson of local yeoman farmers, was the local schoolmaster for fifty years.

At 18 he had taken responsibility for the Charity School established early in the century which had land adjoining the church including a master's house. He was advertising for additional paying pupils in the Bath papers from at least 1755. The Diocesan Visitation Returns in 1783 noted the Charity School to be in a flourishing state for thirty boys and girls and an advertisement of the same year gave the rate for additional pay scholars at 12 guineas a year. His will listed extensive school and property interests (along with all my musical books and instruments). One of the houses in which he had part ownership was The Wilderness, next to the church, inherited by his wife and her sisters in 1748.

His grandfather, a first George (1728-96), son and grandson of local yeoman farmers, was the local schoolmaster for fifty years.

At 18 he had taken responsibility for the Charity School established early in the century which had land adjoining the church including a master's house. He was advertising for additional paying pupils in the Bath papers from at least 1755. The Diocesan Visitation Returns in 1783 noted the Charity School to be in a flourishing state for thirty boys and girls and an advertisement of the same year gave the rate for additional pay scholars at 12 guineas a year. His will listed extensive school and property interests (along with all my musical books and instruments). One of the houses in which he had part ownership was The Wilderness, next to the church, inherited by his wife and her sisters in 1748.

|

Grandfather George's eldest son, a second George (1759-1842), carried on his father's schoolmastering businesses for a further forty years. A 1834 Charity Commissioners’ Report noted that he succeeded his father in 1796 and that in 1834 he had thirty free scholars and ten pay scholars (seldom classed together). He was active in the local community as churchwarden, and as vestry clerk for over thirty years.

The second George's only son was our George and he may also have been involved in running the Charity School because, although the 1834 report is explicit that it was his father who did so, his father was 75 in 1834. The report referred to the schoolmaster as The Rev George Mullins, and George was also advertising for paying pupils in the 1830s. |

Education

The Rev George was ordained in 1823. He was one among a substantial minority of those ordained at the time without benefit of university education and therefore having to provide testimonials from three beneficed clergymen and evidence that they had clerical employment into which to enter. Local connections seem to have come into play. The non-resident rector of the neighbouring parish of Ditteridge (the Rev JL Willis) was willing to appoint him initially as assistant curate and he had written to his father to say that he was willing to resign his living to your son as soon as he is qualified to take it.

The Rev George was ordained in 1823. He was one among a substantial minority of those ordained at the time without benefit of university education and therefore having to provide testimonials from three beneficed clergymen and evidence that they had clerical employment into which to enter. Local connections seem to have come into play. The non-resident rector of the neighbouring parish of Ditteridge (the Rev JL Willis) was willing to appoint him initially as assistant curate and he had written to his father to say that he was willing to resign his living to your son as soon as he is qualified to take it.

|

Willis, along with the vicar of Box and the Rev WL Bowles of Bremhill, certified to the Bishop that he was a suitable candidate for ordination as deacon. Less than a year later, Willis and Bowles, this time along with the rector of Great Chalfield (Rev Richard Warner), certified that he was a suitable for ordination as priest, and Warner now also appointed him as assistant curate there.

The early editions of Crockford's Clerical Directory show that he continued to hold the dual posts of rector of Ditteridge (a living worth £110 pa) and assistant curate of Great Chalfield for twenty seven years, until he was appointed as the rector of Great Chalfield (a living worth £180). Ditteridge's £110 pa would have been a welcome basic income, but the share of Warner's larger stipend, which he would have been paid as his assistant curate, and his school income would have been needed to make it up to a sum on which to live well and bring up a family. The average value of a living in 1838 was £285 pa and the Pluralities Act that year (to stop priests holding multiple benefices) recognised some of its provisions could not apply to those worth £100 pa or less. |

The Rev WL Bowles' Letter

Although we do not know a lot about his life at this time, we do know what he was doing on one evening in the 1830s. A letter survives dated Thursday 10th inviting him to dinner. It came from the Rev WL Bowles, who was a contemporary of his father, and there is obviously some long-standing connection as Bowles had signed the certificates in support of his ordinations. Bowles happens to have a place in literary history; his poetry was admired by Coleridge, Wordsworth and Southey and he helped revive the sonnet form; and his criticism was memorably criticised by Lord Byron. Bowles’ letter thanked him for a fish so magnificent and invited him over to help eat it: you will receive this at ten o'clock - harness the horse and be here at five - you may sleep here if more convenient. The impression is one of a leisured, clerical circle and Bowles names the other intended guests as the Doctor of Corsham, Sylvanus Urban and the Rev John Skinner of Camerton.

Skinner's diaries are in the British Museum and so it is possible to pin the meal down to 11 July 1834 and to know a number of details about it. The fish had been bred in a pond in George’s garden. Skinner says he had seen it there a year earlier when he had been to view Roman remains in the garden. It then weighed two pounds and Skinner was impressed that it had grown to four and a half pounds in so short a time. There was heated conversation about Grey resigning as Prime Minister that month having failed to get support for an Irish Coercion Bill. Skinner's diaries also show how common were long trips on horseback like the one George made that day and would have needed to make quite often between Box and Great Chalfield.

Meanwhile, Sylvanus Urban is the pseudonym of the editors of the Gentlemen's Magazine with whom Bowles worked closely. The wheels of connection extend to the fact that the magazine had published an article three years earlier about the Roman remains (additional to those uncovered by the first George Mullins) discovered when work was being done at The Wilderness, and published an article much later in 1854 about wall paintings discovered at Ditteridge Church.

Although we do not know a lot about his life at this time, we do know what he was doing on one evening in the 1830s. A letter survives dated Thursday 10th inviting him to dinner. It came from the Rev WL Bowles, who was a contemporary of his father, and there is obviously some long-standing connection as Bowles had signed the certificates in support of his ordinations. Bowles happens to have a place in literary history; his poetry was admired by Coleridge, Wordsworth and Southey and he helped revive the sonnet form; and his criticism was memorably criticised by Lord Byron. Bowles’ letter thanked him for a fish so magnificent and invited him over to help eat it: you will receive this at ten o'clock - harness the horse and be here at five - you may sleep here if more convenient. The impression is one of a leisured, clerical circle and Bowles names the other intended guests as the Doctor of Corsham, Sylvanus Urban and the Rev John Skinner of Camerton.

Skinner's diaries are in the British Museum and so it is possible to pin the meal down to 11 July 1834 and to know a number of details about it. The fish had been bred in a pond in George’s garden. Skinner says he had seen it there a year earlier when he had been to view Roman remains in the garden. It then weighed two pounds and Skinner was impressed that it had grown to four and a half pounds in so short a time. There was heated conversation about Grey resigning as Prime Minister that month having failed to get support for an Irish Coercion Bill. Skinner's diaries also show how common were long trips on horseback like the one George made that day and would have needed to make quite often between Box and Great Chalfield.

Meanwhile, Sylvanus Urban is the pseudonym of the editors of the Gentlemen's Magazine with whom Bowles worked closely. The wheels of connection extend to the fact that the magazine had published an article three years earlier about the Roman remains (additional to those uncovered by the first George Mullins) discovered when work was being done at The Wilderness, and published an article much later in 1854 about wall paintings discovered at Ditteridge Church.

|

Marriage and Problems

George had already been ordained more than ten years when on 5 January 1835, a few months after the meal at Bremhill, he married Susannah Gardiner in St Paul’s, Bristol. Her parents, Joel and Mary Anne, both came from hat-manufacturing families. The first surviving census returns are for 1841. This gave George and Susannah as living in Box at Church House (which we know to be The Wilderness) already with five children: George Henry, Robert John (staying with his maternal grandmother at Westbury-on-Trym), twins Henrietta and Mary, and a sixteen day old baby not yet named Joel Francis. George’s parents in their 80s were living near by. The house, however, was heavily indebted, very complicated legal transactions having followed the buying out of other interested parties, and he was forced to sell it the following year. They were then leaving a previously remote village which was undergoing dramatic change as Brunel and thousands of navvies dug what was then the longest railway tunnel in the world through a neighbouring hill. The 1851 census gave the age and place of birth of all those listed so we can follow their progression: a sixth child, Edwin Herbert, was born at Ditteridge in 1844, and a seventh and eighth (Elizabeth Susannah and Hariette Lydia) at Corsham in 1846 and 1849. We do not know where the family lived in Ditteridge: it is just possible that they moved into an existing parsonage but it is much more likely that no such house existed and he had to rent a house which could have been a strain both financially and practically. |

Finding a permanent house in Corsham may have been a very welcome development. The home was the Master's House at Corsham's Hungerford Almshouses.

The Almshouses had a school attached to them, although those reporting for the Charity Commissioners in 1834 had been there as well and noted that no boys had been taught for forty years. Members of the patron's family were corresponding in 1845. They did not believe there was any justification for taking free pupils but one wrote to another I think it could be well to appoint a new Master without delay and if he is disposed to have a school it may be a good thing.

It appears that George’s needs and those of the Almshouses came together. The house, and possibly room for potential paying pupils, are likely to have been the main attraction as the Master's stipend was only £20 pa.

It appears that George’s needs and those of the Almshouses came together. The house, and possibly room for potential paying pupils, are likely to have been the main attraction as the Master's stipend was only £20 pa.

Life at That Time

The best idea of the sort of world in which George was then living may come not from historical sources but from fiction. In 1855 Anthony Trollope published his novel The Warden which is set in a typical west country almshouse where the picturesque row of small houses for the bedesmen (occupants of an almshouse) was in the shadow of a much grander warden's house with its pleasant garden. Its cello-playing warden was also incumbent of a parish worth £80 pa, a few miles away, and got embroiled in disputes about how far the founder's original intentions were being carried out. Trollope's almshouse was in a Cathedral city, his warden had twelve rather than six bedesmen and no school, the particular scandal revolves around his warden's income of £400 pa rather than £20 pa, and we do not know whether George Mullins shared his grandfather's musical ability, but the whole appearance and atmosphere of Hiram's Hospital, Barchester, and the clerical circle surrounding it is likely to be close to the one at the Hungerford Almshouses, Corsham, at the same time.

Two of the Mullins' children died in Corsham almshouse. Lydia died aged 4 in 1853. Her brother Robert was 15 at the time and there is an echo of the family’s grief in his diary written far from home on New Year’s Eve 1856: three years today since my little sister Lydia was buried on that cold December day and a few weeks later poor little Lydia’s birthday. Francis died aged 17 in 1859, news received far away by Robert who recorded my poor brother Frank taken off suddenly to a better world.

The education of George and Susannah’s elder sons was an experience of a new kind of Christian approach to the developing English Public School following the famous Headmastership of Thomas Arnold at Rugby until 1842. Henry was one of the early pupils at Marlborough, established in 1843, less than twenty miles from Corsham, mainly for the sons of clergymen. Robert, having sung in the choir at New College, Oxford, was one of the Rev Nathaniel Woodard’s pupils as far away as Shoreham, at what was to develop into the schools at Ardingly, Hurstpierpoint and Lancing and into the whole federation of Woodard Corporation Schools.

Problems Mount

But the financial situation was either dire or deteriorated. Inclusive fees at Marlborough were 30 guineas a year from clergy sons and Henry was able to proceed from there to Oxford in 1855. Sending Robert to Shoreham, however, may have been because fees there were only 18 guineas and, the year before Henry went to Oxford, Robert was instead sent off to South Africa as catechist in a pioneering missionary party aged 16. In 1857 his diary comments on his necessary mission expenditure (it squashes my object of sending money home to help father) which states the situation clearly. The following year a local gentlemen wrote to the Inspector of Schools to say that it was unreasonable to ask the Master to teach and to manage and repair the almshouses for £20 pa, and George was writing unsuccessfully to the Charity Commissioners for help with urgent repairs. Possibly unreliable memories in the early twentieth century reported that he was stranded without pupils because of other schools in the neighbourhood.

It is also likely that, although he was only 58, he was becoming or had already become ill. He did not sign any of the registers at Great Chalfield after February 1859 and in December Robert’s diary commented bad news about father and in May 1860 mother writes that they have taken father to Eyresham (Eynsham); I hope it will do him good, but I fear nothing can.

The best idea of the sort of world in which George was then living may come not from historical sources but from fiction. In 1855 Anthony Trollope published his novel The Warden which is set in a typical west country almshouse where the picturesque row of small houses for the bedesmen (occupants of an almshouse) was in the shadow of a much grander warden's house with its pleasant garden. Its cello-playing warden was also incumbent of a parish worth £80 pa, a few miles away, and got embroiled in disputes about how far the founder's original intentions were being carried out. Trollope's almshouse was in a Cathedral city, his warden had twelve rather than six bedesmen and no school, the particular scandal revolves around his warden's income of £400 pa rather than £20 pa, and we do not know whether George Mullins shared his grandfather's musical ability, but the whole appearance and atmosphere of Hiram's Hospital, Barchester, and the clerical circle surrounding it is likely to be close to the one at the Hungerford Almshouses, Corsham, at the same time.

Two of the Mullins' children died in Corsham almshouse. Lydia died aged 4 in 1853. Her brother Robert was 15 at the time and there is an echo of the family’s grief in his diary written far from home on New Year’s Eve 1856: three years today since my little sister Lydia was buried on that cold December day and a few weeks later poor little Lydia’s birthday. Francis died aged 17 in 1859, news received far away by Robert who recorded my poor brother Frank taken off suddenly to a better world.

The education of George and Susannah’s elder sons was an experience of a new kind of Christian approach to the developing English Public School following the famous Headmastership of Thomas Arnold at Rugby until 1842. Henry was one of the early pupils at Marlborough, established in 1843, less than twenty miles from Corsham, mainly for the sons of clergymen. Robert, having sung in the choir at New College, Oxford, was one of the Rev Nathaniel Woodard’s pupils as far away as Shoreham, at what was to develop into the schools at Ardingly, Hurstpierpoint and Lancing and into the whole federation of Woodard Corporation Schools.

Problems Mount

But the financial situation was either dire or deteriorated. Inclusive fees at Marlborough were 30 guineas a year from clergy sons and Henry was able to proceed from there to Oxford in 1855. Sending Robert to Shoreham, however, may have been because fees there were only 18 guineas and, the year before Henry went to Oxford, Robert was instead sent off to South Africa as catechist in a pioneering missionary party aged 16. In 1857 his diary comments on his necessary mission expenditure (it squashes my object of sending money home to help father) which states the situation clearly. The following year a local gentlemen wrote to the Inspector of Schools to say that it was unreasonable to ask the Master to teach and to manage and repair the almshouses for £20 pa, and George was writing unsuccessfully to the Charity Commissioners for help with urgent repairs. Possibly unreliable memories in the early twentieth century reported that he was stranded without pupils because of other schools in the neighbourhood.

It is also likely that, although he was only 58, he was becoming or had already become ill. He did not sign any of the registers at Great Chalfield after February 1859 and in December Robert’s diary commented bad news about father and in May 1860 mother writes that they have taken father to Eyresham (Eynsham); I hope it will do him good, but I fear nothing can.

In the 1861 census they were still at Corsham Almshouses, although the enumerator spells the name Mullings. George’s occupation was recorded as both Rector of Great Chalfield and Master of the Corsham Almshouse, generously bracketed across two columns. All six inmates were named, as is one sixteen-year old servant. Henry was at home (the entry which should give his occupation instead proudly gives his Oxford degree and college) but the only other one of the six surviving children there was 15 year old Bessie. Robert was recorded at St Augustine’s College, Canterbury, where he was training for ordination, having returned the previous year after nearly six years away; he was to return to the eastern Cape of South Africa and have a large family there. Ettie was recorded as a governess in a barrister’s home outside Lacock quite near Corsham; she was to marry a Milton Druce and bring up her family in the Oxford area. Her twin, Mary, and new husband, Dr Henry Spencer, himself born in Chippenham, were recorded in Eynsham; she was to die five years later, their only child also having died. Our Edwin may be the one recorded at school in Newark; he was to be ordained like his older brothers and brought up his family in Derbyshire.

Leaving Corsham

Within a few month, however, they had gone. A near contemporary records that The Rev Geo Mullins (son of Mullins, a very respectable old man, formerly Parish Clerk of Box) resigned the Almshouses August 1861 from declining health... went to Bath, had giddiness of the head and fits. Reports from Robert's diary state that his mother was not able to be present at his wedding in Dorset 1862 as she could not leave her invalid husband, although they are there in a large group photograph taken at Henry’s wedding near their home in Oxford two years later. He was still rector of Great Chalfield when he died on 29 April 1867 at what seems to have been his home in Park Town. His funeral took place at St Philip and St James’ (where his son Henry had been assistant curate) and he was buried at St Sepulchre’s Cemetery. The grant of probate a couple of months later noted that effects were worth less than £1,500 and describe him as formerly of Box.

Susannah and Bessie moved to Bromley College, a form of almshouse for clergy widows of limited means. They remained there until 1878 when they moved to Fyfield to live with Ettie Druce and her family and it was there that Susannah died eighteen months later. Bessie continued to live with members of the Druce family at different times over nearly fifty further years, dying in 1928 and being buried in her parents’ grave.

The line of Mullins schoolmasters, which had begun with George's grandfather in Box in 1746, continued in a fourth generation into the twentieth century with the two eldest sons, both of whom were themselves born in Box. Henry taught at Magdalen College School and then for over thirty years at Uppingham where he was a housemaster under the reforming headmaster Edward Thring who continued shaping the new style of Christian Public School. Robert’s main work was at what was then called a Kaffir College for a similar length of time.

Within a few month, however, they had gone. A near contemporary records that The Rev Geo Mullins (son of Mullins, a very respectable old man, formerly Parish Clerk of Box) resigned the Almshouses August 1861 from declining health... went to Bath, had giddiness of the head and fits. Reports from Robert's diary state that his mother was not able to be present at his wedding in Dorset 1862 as she could not leave her invalid husband, although they are there in a large group photograph taken at Henry’s wedding near their home in Oxford two years later. He was still rector of Great Chalfield when he died on 29 April 1867 at what seems to have been his home in Park Town. His funeral took place at St Philip and St James’ (where his son Henry had been assistant curate) and he was buried at St Sepulchre’s Cemetery. The grant of probate a couple of months later noted that effects were worth less than £1,500 and describe him as formerly of Box.

Susannah and Bessie moved to Bromley College, a form of almshouse for clergy widows of limited means. They remained there until 1878 when they moved to Fyfield to live with Ettie Druce and her family and it was there that Susannah died eighteen months later. Bessie continued to live with members of the Druce family at different times over nearly fifty further years, dying in 1928 and being buried in her parents’ grave.

The line of Mullins schoolmasters, which had begun with George's grandfather in Box in 1746, continued in a fourth generation into the twentieth century with the two eldest sons, both of whom were themselves born in Box. Henry taught at Magdalen College School and then for over thirty years at Uppingham where he was a housemaster under the reforming headmaster Edward Thring who continued shaping the new style of Christian Public School. Robert’s main work was at what was then called a Kaffir College for a similar length of time.

Mullins' Tombs in Box Churchyard

There are two family vaults prominently placed at the northwest corner of the churchyard. They reflect the importance of members of the family in the history of the village and particularly over church administration and the teaching of Box's young people in the Charity School.

There are two family vaults prominently placed at the northwest corner of the churchyard. They reflect the importance of members of the family in the history of the village and particularly over church administration and the teaching of Box's young people in the Charity School.

Family Tree

Corsham Reunion, 1890s

Here is one of George's surviving children at a reunion when Robert was in England in the 1890s. The three bearded priests are Robert (standing), Henry (seated, with his wife Jessie next to him) and Edwin (in the window). Their sisters are in the window: Bessie (top left) and Ettie (bottom right). The young girl on the extreme left is Robert’s daughter Hilda (later Rivett-Carnac) and the one on the extreme right is Henry’s daughter Agnes.

Here is one of George's surviving children at a reunion when Robert was in England in the 1890s. The three bearded priests are Robert (standing), Henry (seated, with his wife Jessie next to him) and Edwin (in the window). Their sisters are in the window: Bessie (top left) and Ettie (bottom right). The young girl on the extreme left is Robert’s daughter Hilda (later Rivett-Carnac) and the one on the extreme right is Henry’s daughter Agnes.