|

Box Charity School Rev Canon John Ayers All rights reserved April 2017 John's article is reproduced from his talk to Box GIGs earlier this year. This is the first article in a four-part series about the history of Box School. This is John's story of the old Charity School. Like spelling the word banana, I know how it starts, but my difficulty is knowing when to stop. So let me introduce you to three men: George Millard; George Mullins; Edward Gardiner. Now I am going to ask you to use your imaginations. |

A rider on a muddy horse pauses as he carefully picks his way down a steep track towards the valley bottom. He is 30 years old, and he wears a full-skirted coat of black, and his white cravat falls in double bands over his high buttoned long black waistcoat, proclaiming him to be a professional man; a lawyer perhaps, setting out to draw up a will or a mortgage or a marriage settlement, or a physician making his way towards the city of Bath, now one of England's top ten towns with a rising population of 2,000. Or is he a clerk in holy orders? Perhaps a non-resident or pluralist parson with a cut-price curate left at home to do his duties, for a quarter of all parishes are left with no parson of their own. If he is a parson, unless he has a generous lay patron or extensive glebe-land to farm, he is unlikely to do well. In any case, he is not expected to do more than christen, marry and bury his flock, preach on Sunday, and visit the sick if sent for. He certainly must not be enthusiastic, a very dirty word indeed. But since this is the year 1707, be he parson, lawyer or doctor, he will at least probably have a university degree – Oxford, Cambridge or Dublin – and like all clergy, doctors and lawyers he wears a grey scratch wig.

Rev George Millard

So let me introduce you to our rider. This is Parson George Millard or Miller. Born in Boxwell in Gloucestershire, he matriculated from Queen's College Oxford in 1695, graduated Bachelor of Arts in 1698 at the age of 21, soon after which he took holy orders and was duly presented in 1701 by George Ducket Esq to the small living at Calstone, which is a couple of miles beyond Calne. In 1704 he proceeded to his Master's degree. In 1707 he was presented to the Vicarage of Box, the patron being George Speke Petty Esq, husband of Dame Rachel Speke of Hazelbury. Five years later he was also given the sinecure rectory of Hazelbury, which had been in the gift of the Queen. Together these three parishes would provide a middling but comfortable income to see him through to his death in 1740.

Box was a small and rather inaccessible village. Where the Great West Road runs across from Rudloe Farm to Chapel Field through the open un-enclosed Box Fields, John Speed’s map gives the directions For Box turn in at any field gate. The total parish population is under 500 , but we must bear in mind that the whole of England has a population of only five and a half million. England is a pre-industrial land of small villages, where power is in the hands of very few – squire’s law, parson’s creed.

It is also an insecure land, yearning for stability. Less than twenty years before the king had been chased from his throne and protestant Dutch King William had brought in what the Whig party were calling the glorious revolution. Before that the countryside of the West of England had been convulsed with the Monmouth rebellion and its aftermath, when the vengeful Judge Jeffries had come to Doctor's Hill. The older members of the community would pass on their parents' tales of the Battle of Lansdown, the skirmishing around Bathford, the royalist retreat through Chippenham and the subsequent years of the Commonwealth when the disgraced Vicar of Box had been ejected from his church, leaving bitter divisions and differences behind him. Everything now hung on the Protestant Succession, a national church, and the 1690 Act of Toleration.

Life in Parson George Millard’s world was lived to the full, but it was lived on the edge of violence. The destitute and the under-classes were regarded as a constant threat, and the Elizabethan poor-law was quite inadequate to deal with them. All it really amounted to was three nights in the lock-up and then move them on, back towards the village in which they were born. If they were truly local they became a charge on the parish and tuppence on the Rates.

People were afraid of poverty and they were afraid of the poor. But this new parson had different ideas. It began with a gentlemen's interest group. In 1699 a number of concerned Christian gentlemen, meeting in a London coffee house, had banded together to write to all Church of England clergy with a plan, proposing the formation of a new society. Where the Government would not act, then Societies were the thing. There was a Society for the Reformation of Manners; there was a society for the Repression of Vice; there was a Society for the Prosecution of Felons. But prevention was better than cure. And surely a better way would be to gentle the masses. This was to be The Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SPCK for short). The letter was sent out, but it drew no response from the then vicar of Box, John Philips, nor from Andrew Verriard, the Rector of Hazelbury, or James Butler, the Rector of Ditteridge. None of the Bath clergy had responded either. George Millard would change all that.

The heart of the SPCK plan was simply education. Establishing what became known as charity schools, and George was a paid-up corresponding member. The Society then published a how-to-do-it manual, called The Christian Schoolmaster, which made it clear that such schools were to have the highest professional standards, and be based for funding on local partnership and voluntarism. No sooner was he instituted than he began to put things into practice. First he won the moral and financial support of Dame Rachel Speke. Then local worthies had to be convinced; not everyone thought education for the poor a good idea. Instead of making them good servants, surely education would teach them to despise their lot in life. Instead of teaching them subordination, it would render them fractious. Why would a child learn to read when every hour must be spent in honest toil?

Rev George Millard

So let me introduce you to our rider. This is Parson George Millard or Miller. Born in Boxwell in Gloucestershire, he matriculated from Queen's College Oxford in 1695, graduated Bachelor of Arts in 1698 at the age of 21, soon after which he took holy orders and was duly presented in 1701 by George Ducket Esq to the small living at Calstone, which is a couple of miles beyond Calne. In 1704 he proceeded to his Master's degree. In 1707 he was presented to the Vicarage of Box, the patron being George Speke Petty Esq, husband of Dame Rachel Speke of Hazelbury. Five years later he was also given the sinecure rectory of Hazelbury, which had been in the gift of the Queen. Together these three parishes would provide a middling but comfortable income to see him through to his death in 1740.

Box was a small and rather inaccessible village. Where the Great West Road runs across from Rudloe Farm to Chapel Field through the open un-enclosed Box Fields, John Speed’s map gives the directions For Box turn in at any field gate. The total parish population is under 500 , but we must bear in mind that the whole of England has a population of only five and a half million. England is a pre-industrial land of small villages, where power is in the hands of very few – squire’s law, parson’s creed.

It is also an insecure land, yearning for stability. Less than twenty years before the king had been chased from his throne and protestant Dutch King William had brought in what the Whig party were calling the glorious revolution. Before that the countryside of the West of England had been convulsed with the Monmouth rebellion and its aftermath, when the vengeful Judge Jeffries had come to Doctor's Hill. The older members of the community would pass on their parents' tales of the Battle of Lansdown, the skirmishing around Bathford, the royalist retreat through Chippenham and the subsequent years of the Commonwealth when the disgraced Vicar of Box had been ejected from his church, leaving bitter divisions and differences behind him. Everything now hung on the Protestant Succession, a national church, and the 1690 Act of Toleration.

Life in Parson George Millard’s world was lived to the full, but it was lived on the edge of violence. The destitute and the under-classes were regarded as a constant threat, and the Elizabethan poor-law was quite inadequate to deal with them. All it really amounted to was three nights in the lock-up and then move them on, back towards the village in which they were born. If they were truly local they became a charge on the parish and tuppence on the Rates.

People were afraid of poverty and they were afraid of the poor. But this new parson had different ideas. It began with a gentlemen's interest group. In 1699 a number of concerned Christian gentlemen, meeting in a London coffee house, had banded together to write to all Church of England clergy with a plan, proposing the formation of a new society. Where the Government would not act, then Societies were the thing. There was a Society for the Reformation of Manners; there was a society for the Repression of Vice; there was a Society for the Prosecution of Felons. But prevention was better than cure. And surely a better way would be to gentle the masses. This was to be The Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SPCK for short). The letter was sent out, but it drew no response from the then vicar of Box, John Philips, nor from Andrew Verriard, the Rector of Hazelbury, or James Butler, the Rector of Ditteridge. None of the Bath clergy had responded either. George Millard would change all that.

The heart of the SPCK plan was simply education. Establishing what became known as charity schools, and George was a paid-up corresponding member. The Society then published a how-to-do-it manual, called The Christian Schoolmaster, which made it clear that such schools were to have the highest professional standards, and be based for funding on local partnership and voluntarism. No sooner was he instituted than he began to put things into practice. First he won the moral and financial support of Dame Rachel Speke. Then local worthies had to be convinced; not everyone thought education for the poor a good idea. Instead of making them good servants, surely education would teach them to despise their lot in life. Instead of teaching them subordination, it would render them fractious. Why would a child learn to read when every hour must be spent in honest toil?

Box Charity School Founded

A start was made. In a room above the vestry 15 girls and 15 boys (here the Charity Schools were well ahead of their time, being co-educational from the beginning; polite society did not take girls' minds seriously) were taught first their letters from horn books, which were rather like those table tennis bat guides you sometimes find in churches, and then to read. For text books there was the Bible, probably the Geneva Bible for the Authorised Version took some time to catch on, and the Book of Common Prayer, often bound into one volume. They would get the Collects by heart, and recite the catechism, learning to submit myself to all my governors, teachers, spiritual pastors and masters; to order myself lowly and reverently to all my betters... to learn and labour truly to get mine own living, and to do my duty in that state of life unto which it shall please God to call me.

A start was made. In a room above the vestry 15 girls and 15 boys (here the Charity Schools were well ahead of their time, being co-educational from the beginning; polite society did not take girls' minds seriously) were taught first their letters from horn books, which were rather like those table tennis bat guides you sometimes find in churches, and then to read. For text books there was the Bible, probably the Geneva Bible for the Authorised Version took some time to catch on, and the Book of Common Prayer, often bound into one volume. They would get the Collects by heart, and recite the catechism, learning to submit myself to all my governors, teachers, spiritual pastors and masters; to order myself lowly and reverently to all my betters... to learn and labour truly to get mine own living, and to do my duty in that state of life unto which it shall please God to call me.

Not all the charity schools took their children on from reading to writing, but here at Box they certainly did, and thence to basic arithmetic and casting accounts, as well as spinning and knitting.

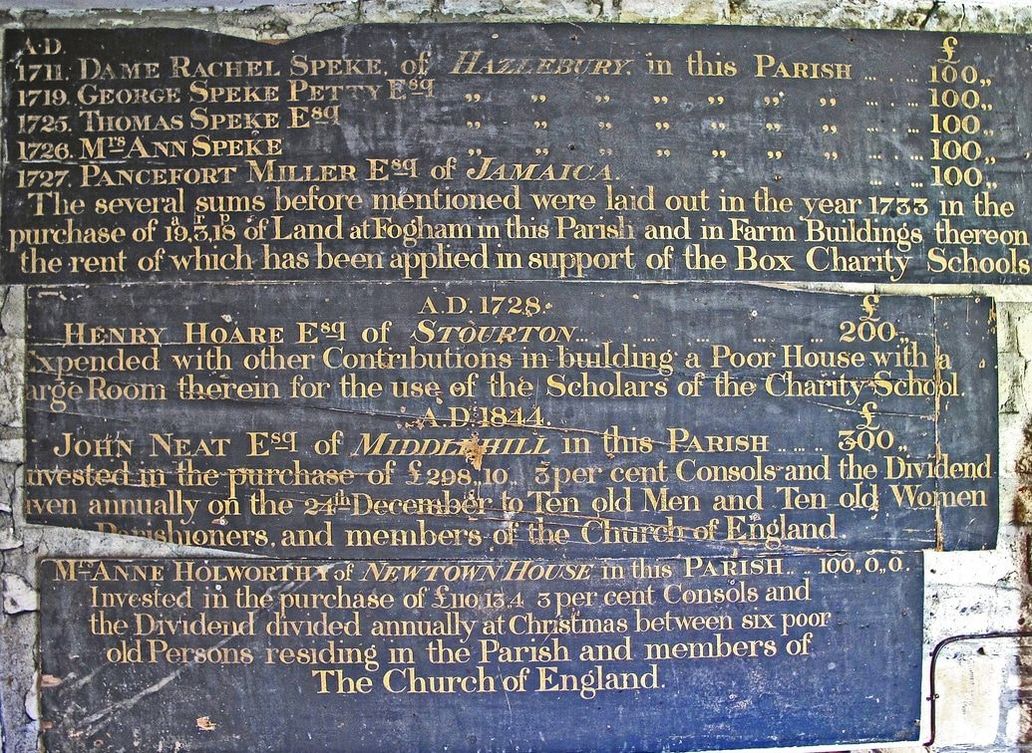

In June 1712 Millard reported that the excellent lady of my parish, the great encourager of our school, viz Dame Rachel Speke, is dead. But Rachel had left in her will the interest of £100 for instructing the poor children to read and furnishing them with books. The school would need far more than this, and (again an SPCK suggestion) a table of benefactors was set up to encourage others. Among the names is that of Pauncefoot Miller, Jamaica Merchant, George Millard's brother. The churchwardens then agreed that the alms offertory at communion (communion was celebrated five times a year) should be added, that an annual charity sermon should be preached, and George himself pledged his Easter dues. Another little earner was the use of a black coffin pall on payment of 1s, or a posher version at 1s.6d. As the disincentive to learning was the loss of a child’s earning capacity, bonus payments were there to be earned. On mastering the alphabet 2s.6d. When able to read a chapter from the Bible and recite the Catechism, 5s. A further 15s when able to cast accounts. Big money.

In 1716 Millard reported that, since the first erecting of this school AD 1708, there have been educated in all and dismissed,

34 children. They went on to trade, to husbandry, to friends, or to family, and on leaving were given a copy for themselves of the Bible and the Prayer Book. One leaver became a replacement for Millard’s own manservant who had died of smallpox, a blessing which I look upon more than sufficient to recompense me for all the care and pains I have hitherto bestowed about the education of the poor children of this parish. He then casually mentioned that, not only had he started a similar school in his other parish, Calston, (this was Calston Wellington, near Calne, a parish, he said, of only four families) but was well on the way to setting up a third in another neighbouring parish where the living was vacant.

So what did he do apart from that? Well, in 1712 he began to pull down and rebuild most of the church, because the congregation was outstripping the church’s accommodation. He added the north aisle, increasing capacity by a further 100. Then galleries were added (we shall hear more of them later). Box pews were built, lined with green and red baize, with butts to enable worshippers to kneel, and candlesticks for illumination so that services were no longer only on a Sunday afternoon.

He provided what was in effect a public reading room or library in church, and set about adult education, or as he put it, in the instructing of such young men and maidens, of the poorer sort, as think themselves too bigg to go to school. In 1716 eight or nine overgrown persons learned to read; in 1717 one member of the adult literacy class was aged over 40. One effect of growing literacy that Millard reports was vocal participation in the liturgy – standing up and taking part in the worship.

Before the school left the church building however, one thing more: music – singing ! Up until now any singing in church had been restricted to the Psalms, and to the parson and a few select performers in the gallery. In 1717 he sent to SPCK for a copy of John Playford’s The Singer’s Guide. This was music for Tate and Brady’s New Version metrical psalms of 1698, which had replaced Sternhold and Hopkins' 1562 Psalms (hence old hundredth, or Cambridge new). Laboriously he prepared manuscript books, and then, practicing with them for two hours a day, in little more than a week the children of the charity school had mastered four tunes. That Sunday the congregation was entranced. Everyone wanted to learn to sing. In no time the children had mastered a further 30 tunes. Choir practices were being held three times a week and more than 160 would turn up from the village. The children were even sent up to Marshfield to demonstrate to them what they could do, and here Sunday worship was preceded by, and followed by, singing. He gave a lovely account of a competition among the children; when it proved impossible to choose between the thirty best performers, the prize was awarded by lot, and the congregation then took up a collection to share out among the unlucky ones.

In June 1712 Millard reported that the excellent lady of my parish, the great encourager of our school, viz Dame Rachel Speke, is dead. But Rachel had left in her will the interest of £100 for instructing the poor children to read and furnishing them with books. The school would need far more than this, and (again an SPCK suggestion) a table of benefactors was set up to encourage others. Among the names is that of Pauncefoot Miller, Jamaica Merchant, George Millard's brother. The churchwardens then agreed that the alms offertory at communion (communion was celebrated five times a year) should be added, that an annual charity sermon should be preached, and George himself pledged his Easter dues. Another little earner was the use of a black coffin pall on payment of 1s, or a posher version at 1s.6d. As the disincentive to learning was the loss of a child’s earning capacity, bonus payments were there to be earned. On mastering the alphabet 2s.6d. When able to read a chapter from the Bible and recite the Catechism, 5s. A further 15s when able to cast accounts. Big money.

In 1716 Millard reported that, since the first erecting of this school AD 1708, there have been educated in all and dismissed,

34 children. They went on to trade, to husbandry, to friends, or to family, and on leaving were given a copy for themselves of the Bible and the Prayer Book. One leaver became a replacement for Millard’s own manservant who had died of smallpox, a blessing which I look upon more than sufficient to recompense me for all the care and pains I have hitherto bestowed about the education of the poor children of this parish. He then casually mentioned that, not only had he started a similar school in his other parish, Calston, (this was Calston Wellington, near Calne, a parish, he said, of only four families) but was well on the way to setting up a third in another neighbouring parish where the living was vacant.

So what did he do apart from that? Well, in 1712 he began to pull down and rebuild most of the church, because the congregation was outstripping the church’s accommodation. He added the north aisle, increasing capacity by a further 100. Then galleries were added (we shall hear more of them later). Box pews were built, lined with green and red baize, with butts to enable worshippers to kneel, and candlesticks for illumination so that services were no longer only on a Sunday afternoon.

He provided what was in effect a public reading room or library in church, and set about adult education, or as he put it, in the instructing of such young men and maidens, of the poorer sort, as think themselves too bigg to go to school. In 1716 eight or nine overgrown persons learned to read; in 1717 one member of the adult literacy class was aged over 40. One effect of growing literacy that Millard reports was vocal participation in the liturgy – standing up and taking part in the worship.

Before the school left the church building however, one thing more: music – singing ! Up until now any singing in church had been restricted to the Psalms, and to the parson and a few select performers in the gallery. In 1717 he sent to SPCK for a copy of John Playford’s The Singer’s Guide. This was music for Tate and Brady’s New Version metrical psalms of 1698, which had replaced Sternhold and Hopkins' 1562 Psalms (hence old hundredth, or Cambridge new). Laboriously he prepared manuscript books, and then, practicing with them for two hours a day, in little more than a week the children of the charity school had mastered four tunes. That Sunday the congregation was entranced. Everyone wanted to learn to sing. In no time the children had mastered a further 30 tunes. Choir practices were being held three times a week and more than 160 would turn up from the village. The children were even sent up to Marshfield to demonstrate to them what they could do, and here Sunday worship was preceded by, and followed by, singing. He gave a lovely account of a competition among the children; when it proved impossible to choose between the thirty best performers, the prize was awarded by lot, and the congregation then took up a collection to share out among the unlucky ones.

|

Expanding the School

So it was that Parson Millard’s school flourished and outgrew its premises. In 1719 Thomas Speke gave land alongside the churchyard, timber was donated, and what is now Springfield Cottages was erected as a proper schoolhouse with 7 rooms and 2 outhouses. The total cost amounted to £107.12.0d. Four years later two cottages and orchards at Henley were given to the school by Christopher Eyre, whose family was beginning to take an interest. In 1727 all the various monies accumulated were used to purchase the tract of land that ran from the Brook, through Bassets and Fogleigh, up to the top of Quarry Hill, and a good stone barn – now a house beside the A4 – was constructed. |

At the cost of £475.19.6d the school now owned a farm worth about £60 a year. This would be the remuneration for a high quality schoolmaster on the London model and the arrangement worked well for the next 150 years. But none of this was without opposition. A vitriolic pamphlet entitled The Fable of the Bees, or Private Vices written by Bernard de Mandeville but published anonymously declared: The more a shepherd and ploughman know of the world, the less fitted he’ll be to go through the fatigue and hardship of it with cheerfulness and equanimity, the eternal response of the haves to the have-nots. Education of the poor was prejudicial to their morals and happiness. Ignorance on the other hand was the opiate of the poor, a cordial administered by the gracious hand of providence.

It also upset those of the second poor – those above, but only just above the bread line, the just about managing. They saw paupers receiving help, and feared that they were being overtaken. The answer then must be Schools of Industry where children would repay expenses by spinning, picking oakum, knitting, or performing menial chores, otherwise known as workhouses. It seemed at the time such a good idea. Millard found a new ally in the widow of Henry Hoar of Stourton, and money was raised for the building of Springfields.

It was at this point that hundreds of charity schools folded. Perhaps Millard was not quite so easily convinced after all, for although the workhouse was built, it was with a separate outside staircase so that the school, on the top floor, would be entirely separated from the adult inmates receiving indoor relief. George Millard died in 1738, leaving a wife, a daughter Lucy, sufficient money to distribute bread to the poor of Box on the third day after his interment, and instructions that all of his sermon notes should then be burnt.

It also upset those of the second poor – those above, but only just above the bread line, the just about managing. They saw paupers receiving help, and feared that they were being overtaken. The answer then must be Schools of Industry where children would repay expenses by spinning, picking oakum, knitting, or performing menial chores, otherwise known as workhouses. It seemed at the time such a good idea. Millard found a new ally in the widow of Henry Hoar of Stourton, and money was raised for the building of Springfields.

It was at this point that hundreds of charity schools folded. Perhaps Millard was not quite so easily convinced after all, for although the workhouse was built, it was with a separate outside staircase so that the school, on the top floor, would be entirely separated from the adult inmates receiving indoor relief. George Millard died in 1738, leaving a wife, a daughter Lucy, sufficient money to distribute bread to the poor of Box on the third day after his interment, and instructions that all of his sermon notes should then be burnt.

Enter George Mullins

Opening the Bath Chronicle the headline to an advert might have caught our eye: At Mullins’s Boarding Schools At Box in the County of Wilts. Read on and you would find that for an entrance fee of one guinea, and fees of 12 guineas pa, both boys and girls were boarded. Boys were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, book-keeping, geometry, gauging, surveying etc etc, and girls learnt, alongside the 3r’s, Latin, French, dancing, music, needlework, and if required, drawing.

What had happened was that, at the suggestion of SPCK, charity schools were now taking in the children of local middle class traders as boarders, to be educated alongside the same number of charity children, and the profit from the private fees went towards the cost of the poor. It's interesting how the term bluecoat school, or grey-coat, or red-maids, has now become a mark of distinction ! Yet these are the same schools which once provided uniform clothing for destitute pauper children. Whether here at Box it was blue or grey or whatever we don’t know, only tantalisingly that they were worn, in compliment to Dame Rachel Speke the same colour as her livery.

The schoolmaster was George Mullins, son and grandson of yeoman farmers, born in 1728 at Slade’s Farm. At the age of 18 he took on the job of schoolmaster and Parish Clerk as well. His first duty was indeed to teach the 30 charity children, who were to be admitted in order of application and regardless of age as vacancies occurred, and the rest was all private enterprise. The new parson was more interested in fox-hunting. George did very nicely. The workhouse never at any time reached full capacity, and gradually the school took over the whole of the building.

In 1766 George bought a mill. In 1791 he acquired more property, including part-interest in the Wilderness, inherited by his wife and her sisters in 1748. The whole family were in on the act, so that when in 1796 George Mullins senior died, his son George junior stepped into his shoes, along with his daughter Jane, his son Edward, and his son’s wife Rachel. He carried on the business for a further forty years. There was probably involvement of a third generation of Mullins too.

We are able to catch a privileged poignant glimpse into this boarding period in the life of the school. When floorboards were being removed at the time Springfield was being converted to flats a number of sheets of writing came to light. These seem to be pages of rough work, corrected by the schoolmaster, and written by one of the boys. They include school exercises, prayers and collects, and draughts of letters home. They are dated 1821. Dear Aunt, he wrote in flowing copperplate, It is with pleasure I write these few lines to inform that I am in good Health and I Hope that you and Dear Uncle and all dear friends are the same. Please to send me a new pair of shoes and my new suit of clothes as soon as it is sent to you from my Father and all the things that is sent with it. Please to give my love to all my friends. Mr and Mrs Mullins desire their love to you. From Your affectionate nephew W H Kidd. Please to send me a new pair of shoes.

This was then duly censored by the teacher and reduced to: Dear Aunt, It is with pleasure that I write these few lines to inform you that I am in good health and I hope that you, uncle, and my dear friends are the same. Please to send me a new pair of shoes as soon as convenient. Mr and Mrs Mullins desire their compliments. Was he one of those children who, for another 3 guineas, would remain at school over the vacation, not wanted at home: shades of the young Scrooge?

In 1811 SPCK handed its school work over to the National Society (The National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales). The government were getting interested in education, and in 1831 the first grant was made, £2,000, less than to the royal stables. But if there was government money, then government inspectors must be created. Box was inspected for the first time in 1834 and told that the number of free scholars must rise from 30 to 50. There was now competition – free schools in Bath, a flourishing little school in Ditteridge, and Parson Horlock’s daughter was running a little school up at Henley. The school began a long, slow decline.

The Bath Herald ran a column The Church Rambler and eventually it was the turn of Box. Both church and school got a bad press. No church that I know calls more loudly for restoration than Box, though it will require great skill to carry out the work. He described the galleries as being of self-taught genius and rude simplicity, reached from the outside by commonplace steps via a door let into part of one of the windows. The well-to-do had seats under the tower and in the chancel, and had constructed large hat pegs on the walls beside their seats. The reporter was distracted by the sound of dropping marbles and teachers administering the loud occasional smack. Three little boys made a dash for it after the second lesson. He then inspected the school, which he declared to be in such a ruinous state that government aid was refused, The whole place has the air of mouldering decay, gaps in the plaster, rotting joists, and the outhouses abandoned with a stream running through.

Rev Gardiner

But again Box had a new Vicar – this time, Rev Edward Gardiner. He had arrived in the nick of time. First most of the school lands were sold, raising £2,350, retaining only the strip of land over which a tramway ran down from the quarries to the wharf which itself created a useful income of £20 pa. The parish of Ditteridge would transfer its school and school money to Box, and the school at Henley would close. The school cottages were retained, and Bladwells of Bath were contracted for a new, single purpose-built school to be constructed on land given by Colonel Northey. Top school architects were engaged, Hicks of Redruth, to design a suite of three schools in one – infants, girls, boys, each with their own entrance and playground.

At the time of the Church Rambler report the walls were already up and the cost almost subscribed. The whole village felt itself to be on the verge of a new revitalised era. Were all our parish clergy of such mettle as the vicar of Box, neither attacks from without nor dissensions within need make us tremble he wrote. The model building was opened in 1875, and this was substantially the same school as it was in 1970 when I came here as deputy head, a class filling every room, and sliding partitions separating the classrooms. The only trace now of the tiered benches is in the shape of the dado, and outside grooves on the walls witness generations of children using the stone to sharpen their slate pencils. Happily the outside lavatories are long gone.

For 23 years Edward Gardiner faithfully made his calls into the school that he loved, teaching scripture, maths, and Indian clubs (physical exercise equipment). When his health failed him, he left to convalesce in Italy. The children sent him gifts of socks that they knitted.

Opening the Bath Chronicle the headline to an advert might have caught our eye: At Mullins’s Boarding Schools At Box in the County of Wilts. Read on and you would find that for an entrance fee of one guinea, and fees of 12 guineas pa, both boys and girls were boarded. Boys were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, book-keeping, geometry, gauging, surveying etc etc, and girls learnt, alongside the 3r’s, Latin, French, dancing, music, needlework, and if required, drawing.

What had happened was that, at the suggestion of SPCK, charity schools were now taking in the children of local middle class traders as boarders, to be educated alongside the same number of charity children, and the profit from the private fees went towards the cost of the poor. It's interesting how the term bluecoat school, or grey-coat, or red-maids, has now become a mark of distinction ! Yet these are the same schools which once provided uniform clothing for destitute pauper children. Whether here at Box it was blue or grey or whatever we don’t know, only tantalisingly that they were worn, in compliment to Dame Rachel Speke the same colour as her livery.

The schoolmaster was George Mullins, son and grandson of yeoman farmers, born in 1728 at Slade’s Farm. At the age of 18 he took on the job of schoolmaster and Parish Clerk as well. His first duty was indeed to teach the 30 charity children, who were to be admitted in order of application and regardless of age as vacancies occurred, and the rest was all private enterprise. The new parson was more interested in fox-hunting. George did very nicely. The workhouse never at any time reached full capacity, and gradually the school took over the whole of the building.

In 1766 George bought a mill. In 1791 he acquired more property, including part-interest in the Wilderness, inherited by his wife and her sisters in 1748. The whole family were in on the act, so that when in 1796 George Mullins senior died, his son George junior stepped into his shoes, along with his daughter Jane, his son Edward, and his son’s wife Rachel. He carried on the business for a further forty years. There was probably involvement of a third generation of Mullins too.

We are able to catch a privileged poignant glimpse into this boarding period in the life of the school. When floorboards were being removed at the time Springfield was being converted to flats a number of sheets of writing came to light. These seem to be pages of rough work, corrected by the schoolmaster, and written by one of the boys. They include school exercises, prayers and collects, and draughts of letters home. They are dated 1821. Dear Aunt, he wrote in flowing copperplate, It is with pleasure I write these few lines to inform that I am in good Health and I Hope that you and Dear Uncle and all dear friends are the same. Please to send me a new pair of shoes and my new suit of clothes as soon as it is sent to you from my Father and all the things that is sent with it. Please to give my love to all my friends. Mr and Mrs Mullins desire their love to you. From Your affectionate nephew W H Kidd. Please to send me a new pair of shoes.

This was then duly censored by the teacher and reduced to: Dear Aunt, It is with pleasure that I write these few lines to inform you that I am in good health and I hope that you, uncle, and my dear friends are the same. Please to send me a new pair of shoes as soon as convenient. Mr and Mrs Mullins desire their compliments. Was he one of those children who, for another 3 guineas, would remain at school over the vacation, not wanted at home: shades of the young Scrooge?

In 1811 SPCK handed its school work over to the National Society (The National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales). The government were getting interested in education, and in 1831 the first grant was made, £2,000, less than to the royal stables. But if there was government money, then government inspectors must be created. Box was inspected for the first time in 1834 and told that the number of free scholars must rise from 30 to 50. There was now competition – free schools in Bath, a flourishing little school in Ditteridge, and Parson Horlock’s daughter was running a little school up at Henley. The school began a long, slow decline.

The Bath Herald ran a column The Church Rambler and eventually it was the turn of Box. Both church and school got a bad press. No church that I know calls more loudly for restoration than Box, though it will require great skill to carry out the work. He described the galleries as being of self-taught genius and rude simplicity, reached from the outside by commonplace steps via a door let into part of one of the windows. The well-to-do had seats under the tower and in the chancel, and had constructed large hat pegs on the walls beside their seats. The reporter was distracted by the sound of dropping marbles and teachers administering the loud occasional smack. Three little boys made a dash for it after the second lesson. He then inspected the school, which he declared to be in such a ruinous state that government aid was refused, The whole place has the air of mouldering decay, gaps in the plaster, rotting joists, and the outhouses abandoned with a stream running through.

Rev Gardiner

But again Box had a new Vicar – this time, Rev Edward Gardiner. He had arrived in the nick of time. First most of the school lands were sold, raising £2,350, retaining only the strip of land over which a tramway ran down from the quarries to the wharf which itself created a useful income of £20 pa. The parish of Ditteridge would transfer its school and school money to Box, and the school at Henley would close. The school cottages were retained, and Bladwells of Bath were contracted for a new, single purpose-built school to be constructed on land given by Colonel Northey. Top school architects were engaged, Hicks of Redruth, to design a suite of three schools in one – infants, girls, boys, each with their own entrance and playground.

At the time of the Church Rambler report the walls were already up and the cost almost subscribed. The whole village felt itself to be on the verge of a new revitalised era. Were all our parish clergy of such mettle as the vicar of Box, neither attacks from without nor dissensions within need make us tremble he wrote. The model building was opened in 1875, and this was substantially the same school as it was in 1970 when I came here as deputy head, a class filling every room, and sliding partitions separating the classrooms. The only trace now of the tiered benches is in the shape of the dado, and outside grooves on the walls witness generations of children using the stone to sharpen their slate pencils. Happily the outside lavatories are long gone.

For 23 years Edward Gardiner faithfully made his calls into the school that he loved, teaching scripture, maths, and Indian clubs (physical exercise equipment). When his health failed him, he left to convalesce in Italy. The children sent him gifts of socks that they knitted.

|

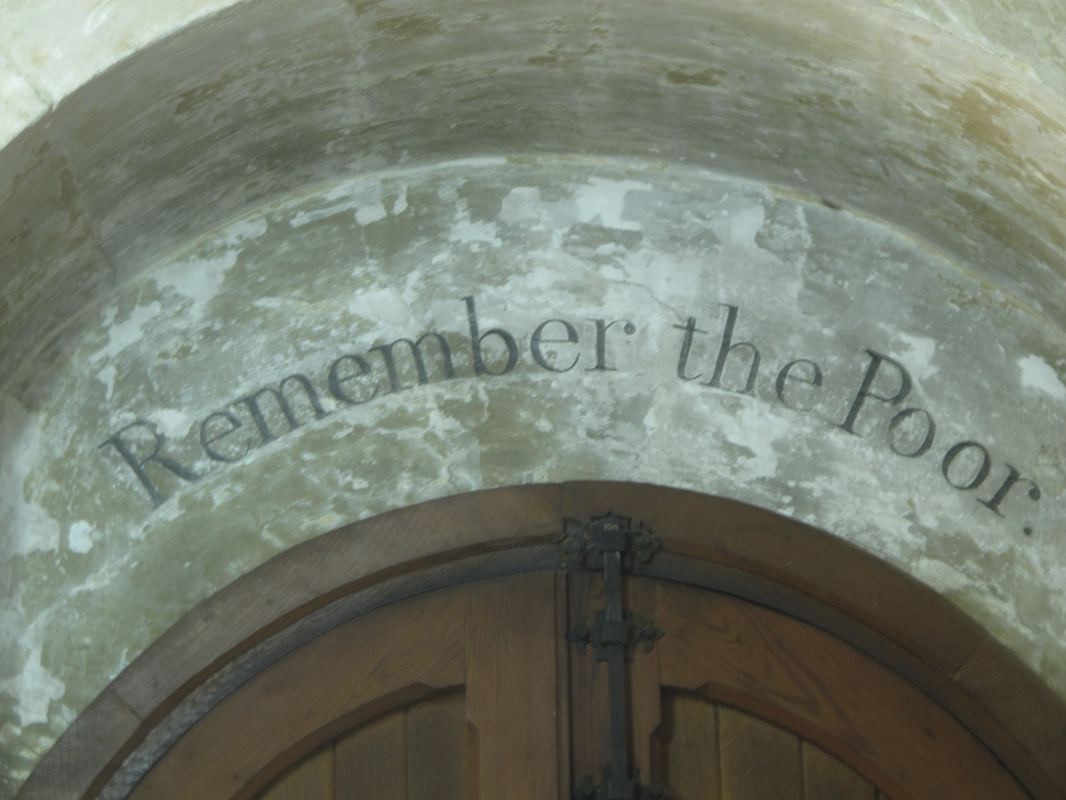

But let me leave you with a double motto and a mystery. The motto is carved above the (rather incongruous) north door of the church, which parson Millard had built. On the outside, to be read by the worshipper entering, are the words This is the house of God; but on the inside, as the worshipper leaves to return again to the world, Remember the poor.

The mystery? The 1728 workhouse inventory lists first the books: 1 Bible, 1 Common Prayer, 2 Psalms, 2 New Testaments, 1 Whole Duty of Man. Then: equipment for cooking and brewing, bedding and furniture, enough for 20 persons. 12 spinning wheels. And chamber pots: 2 pewter, 2 earthenware. The mystery which must challenge any educational historian is this: Who got the pewter pots and who got the earthenware pots, and why? |

We welcome all memories of your time at Box School for inclusion in later publications. In the next issue we record the story of the Foundation of the New Schools in 1875, including the staff and pupils who were the first to enjoy the benefits of state education.