Modern Incomers Alan Payne August 2023

The story of Box village has really been a constant inflow of people taking up new economic opportunities. The diaspora started in prehistory and continued ever since. We see it clearly in the Victorian period when navvies came to excavate Box Tunnel and quarrymen flocked to the area to settle locally. In the nineteenth century Methodists appear to have targeted the village and Irish families were encouraged in the 1930s and 40s to do much of the work restoring the quarries for military use. There was even more influx in the Second World War when the prefabricated bungalows at Rudloe and Boxfields housed miners clearing the quarries and servicemen both British and from Allied countries.

|

Refugees in 1950s and 60s

The influx of newcomers didn’t stop with the end of the Second World War. At the height of the Cold War between the West and Russia in October 1956, people in Hungary rebelled against the Stalinist Russian-controlled government demanding political and economic reforms. The Hungarian Uprising brought an immediate and violent military response and 200,000 refugees sought asylum abroad, most going via neighbouring Austria. By the start of 1957 eight hundred refugees came to Box and were housed in the hostels at Thorneypits. The vicar Tom Selwyn-Smith was able to report: It was a joy that people in Box were able to welcome some of the refugees into their homes .. They are here in this country because the alternatives are either a speedy and merciful death or slavery in Siberia.[1] By March of that year, the vicar commented that the Russian state depicted the insurgents as right-wing fascist reactionaries.[2] Those who have found temporary refuge at Thorney Pits could hardly be less like the portrait given. He said they were waiters, coal miners, glass blowers, farm workers, one from a flour mill, workers in garages and drivers. There is however one strong element amongst them - their Christian commitment. Many of the refugees were young, intellectuals and middle-class families. Right: Laszlo Vertessy (known as Les) was a Hungarian refugee aged 9. He came to see the remains of Thorneypits in 2022 and to recall his short stay in the area (courtesy Carol Payne) |

The Box Youth team played a football match against a scratch Hungarian side in order to integrate the younger refugees. There is a report of a senior football match in the article Hungarian Revolt, which details the seriousness of football, involving a disputed penalty and a threatened walk-off of the Hungarian side. It is recalled that Box won the match which might have, in some way, redeemed the magnificence of the Hungarian national side which beat England 6-3 at Wembley in 1953 and 7-1 in the return fixture in 1954. Of course, with such a disturbed background, not all the Hungarians were saints. PC John Bosley had to arrest one refugee called Joseph Haringozo, who was later charged with multiple robberies in Bristol.

|

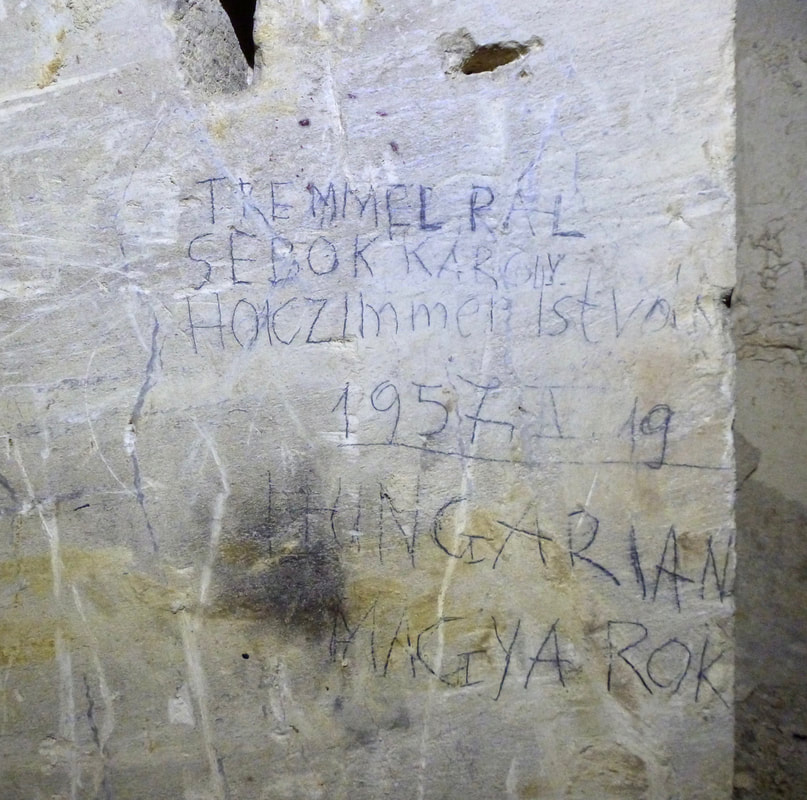

Our culture has benefitted from the Hungarian migrants over the years with chef Egon Ronay, film producers Alexander Korda and Emeric Pressburger and Dire Straits singer Mark Knopfler. The most famous of all the 1956 refugees was Joe Bugner, British heavyweight boxing champion who was ranked amongst superstars like Joe Frasier and Henry Cooper. He twice fought Muhammad Ali in 1973 and 1975. Kevin Ford recalled seeing him in 1956: I once looked through the window and saw them. There was Joe Bugner there. They did traditional Slovak dancing. A few Hungarians stayed in Britain and can still be traced by Hungarian names but most left Box. The fascinating graffiti in Box underground quarries confirms that they were here. Left: Grafitti in the Box underground tunnels probably a young man exploring the area (courtesy Mark Jenkinson) |

Laszlo Vertessy's Story

I came to Box with my parents from Hungary in 1956. My father had worked as a refrigeration service engineer and my mother was a senior book-keeper. My parents weren't actively involved in the uprising against the pro-Russian government but the situation was extremely dangerous, especially after the Soviet army invaded, shooting and imprisoning people at will. I came to Thornypits, Box, with my parents when I was 9 years old, whilst my aunt fled to Norway and married there.

We were housed in one of the hostels off the track leading east from the Bradford Road. We only stayed for a few months but

I remember it well. I knew no English and watched the cinema in the ex-World War 2 camp near Burlington Bunker which we reached by a footpath running parallel with the Bradford Road. We had brought no furniture or other belongings with us, just a change of clothes and a few items in a suitcase, so we ate our meals in the canteen building. I even went to school at Highlands School for a few weeks. While we were in the camp, my parents both worked in the refugees' admin office.

I recall a different football match, organised for the benefit of younger refugees. It was a game for us Hungarian boys against a team from the Corsham Scouts which we played in borrowed kit. I remember the hole in my left foot from a nail sticking through the boot. We won that match 3-1.

I came to Box with my parents from Hungary in 1956. My father had worked as a refrigeration service engineer and my mother was a senior book-keeper. My parents weren't actively involved in the uprising against the pro-Russian government but the situation was extremely dangerous, especially after the Soviet army invaded, shooting and imprisoning people at will. I came to Thornypits, Box, with my parents when I was 9 years old, whilst my aunt fled to Norway and married there.

We were housed in one of the hostels off the track leading east from the Bradford Road. We only stayed for a few months but

I remember it well. I knew no English and watched the cinema in the ex-World War 2 camp near Burlington Bunker which we reached by a footpath running parallel with the Bradford Road. We had brought no furniture or other belongings with us, just a change of clothes and a few items in a suitcase, so we ate our meals in the canteen building. I even went to school at Highlands School for a few weeks. While we were in the camp, my parents both worked in the refugees' admin office.

I recall a different football match, organised for the benefit of younger refugees. It was a game for us Hungarian boys against a team from the Corsham Scouts which we played in borrowed kit. I remember the hole in my left foot from a nail sticking through the boot. We won that match 3-1.

Travellers in Box

Both before and after the Hungarian visitors, there were annual arrivals of migrant vendors rather than persecuted refugees. Bands of travelling communities in the village were commonplace during the Kingsdown Fairs in the late Victorian period, selling horses, offering to tell the future and trying barter. In the 1920s Kathleen Harris recalled them selling handmade goods: gypsy callers among those who supplied our needs at The Old Jockey. They sold clothes-pegs made from saplings whittled into shape at their encampment on Wadswick Common.

Both before and after the Hungarian visitors, there were annual arrivals of migrant vendors rather than persecuted refugees. Bands of travelling communities in the village were commonplace during the Kingsdown Fairs in the late Victorian period, selling horses, offering to tell the future and trying barter. In the 1920s Kathleen Harris recalled them selling handmade goods: gypsy callers among those who supplied our needs at The Old Jockey. They sold clothes-pegs made from saplings whittled into shape at their encampment on Wadswick Common.

By the 1950s and 60s, travelling groups passed through the area to midsummer festivals, often travelling in conveys of caravans causing traffic jams and general disruption on the roads. From 1955 to 1964 Box’s village policeman John Bosley recalled travellers arriving in the village, often prior to journeying down to Glastonbury for a mid-summer or equinox ceremony. He recalled: Every year a load of gypsy travellers came parking on Wadswick Common and they always left a hell of a mess. After a while I used to go and urge them to move on. “We shall be going tomorrow, sir.” They weren't gone tomorrow; they used to try to hold on with all the excuses: “One of our members is ill, sir; one of our members can't travel, sir.”

They lived on the edge of legitimacy, fearful of forms, authority and conformity. But their attitude changed when tragedy struck their community. Heather Meays recalled a funeral organised by her grandfather RJ Dyer and led by her uncle, Sidney Dyer: I particularly remember the funeral of a young gypsy boy, one of the saddest funerals my grandfather had to organise. The young boy was tragically killed in an accident whilst the travellers were camping on Wadswick Common. All the mourners walked behind the hearse from the Common to Box Cemetery where the little boy was buried. My uncle, Sydney Dyer, led the procession. My mother also attended the funeral and told me afterwards that the sisters of the little boy were all dressed in white with white ribbons in their hair. Subsequently, when visiting the cemetery, we would always go to find the tiny grave where a small stone statue of a pony had been placed. The stone blocks placed on Wadswick Common in the 1990s (on the sides of the short cut from The Devizes Road to Hazelbury Manor) were specifically to stop annual gatherings on the Common. It appears to have worked.

Some of our contemporary media denigrates “economic migrants”. But Box has traditionally welcomed thousands of people from outside the village: stone quarrymen, railwaymen, shopkeepers and Irish labourers clearing the tunnels during the Second World War. So what is our problem with those we call "foreigners"? As Vicar Tom Selwyn-Smith said of the Hungarians in March 1957: “In the face of persecution, the enemy is easy enough to recognise. In the face of inertia, the enemy is deceptive”. Les Veressy would love to hear from any other Hungarian refugees who came to the Box area. Please contact us and give your details and we will put you in touch with him.

References

[1] Parish Magazine, January 1957

[2] Parish Magazine, March 1957

[1] Parish Magazine, January 1957

[2] Parish Magazine, March 1957