|

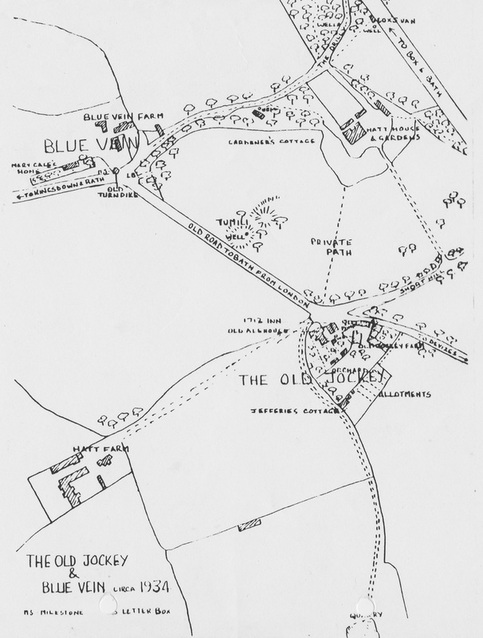

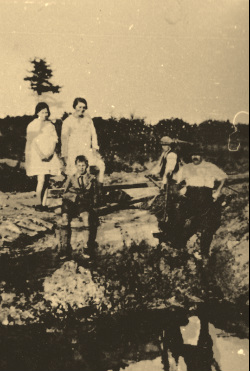

Up the Hill and Down the Hill: My Childhood in a Wiltshire Hamlet Katherine Harris Katherine Harris paints a marvellous picture of the people she encountered at The Old Jockey and of going to the Box Schools in the early 1900s. It was an era now long gone: of horse and cart, earth lavatories and oil stoves for domestic light and heat. We would be delighted to hear of your childhood memories in Box - see Contact tab. Left: Katherine and her parents (All pictures courtesy of Katherine Harris) |

Introduction: The History of The Old Jockey

This hamlet is situated in the south-east of the parish of Box, and at the centre of a district known as Hatt. Hatt was bordered by Wormwood, Wadswick, Longsplatt and an old Roman Road. The line of this old road forms the present boundary between Box and South Wraxall.

In the thirteenth century Reginald de Hatt lived in this minor manor, followed by Robert de Hatte and John atte Hatt in 1485. Later owners were a William Kenyon in 1634 and a George Speke who died in 1652. In 1682 it became the property of Lionel Duckett, Esquire of Hartham. In old documents Hatt is referred to as a farm. The winding road through the area is probably the oldest in Box as it is part of a Ridgeway and links the Cotswold Ridgeway with the ancient Harroway on the Dorset border. On reaching Kingsdown this old thoroughfare veered left towards Bradford-on-Avon but its line there is completely obliterated by the Golf Course. On the side of the old road and near the Old Jockey are tumuli dated circa 500 BC. Maybe the mounds were the inspiration of the place-name of Hatt! Today only Hatt House and Hatt Farm perpetuate the old name.

Hatt House is on the site of an older building and until the early nineteenth century several small dwellings stood alongside the lane leading to the rear entrance. Except for Blue Vein farmhouse and one derelict cottage, these have disappeared. The lane at one time affording the only access to Hatt House leaves the old Ridgeway road by the turnpike cottage and, after passing the big house, continues downhill where it is called the Drilly. From here and through Box Bottoms it continues as a footpath to the village of Box. As the Drilly reaches the lower ground this old track is bisected by the A365, a road completed as late as 1840. Hatt Farm is of this same date. The house and buildings stand in a field and well back from the road. It is a half-mile from Hatt House. The new farmer took over the responsibility of cultivating all the Hatt fields which had been leased piecemeal for many years to local people. It is interesting to note that a 1630 map shows the land at Hatt divided into fields long before the enclosure Acts became law.

This hamlet is situated in the south-east of the parish of Box, and at the centre of a district known as Hatt. Hatt was bordered by Wormwood, Wadswick, Longsplatt and an old Roman Road. The line of this old road forms the present boundary between Box and South Wraxall.

In the thirteenth century Reginald de Hatt lived in this minor manor, followed by Robert de Hatte and John atte Hatt in 1485. Later owners were a William Kenyon in 1634 and a George Speke who died in 1652. In 1682 it became the property of Lionel Duckett, Esquire of Hartham. In old documents Hatt is referred to as a farm. The winding road through the area is probably the oldest in Box as it is part of a Ridgeway and links the Cotswold Ridgeway with the ancient Harroway on the Dorset border. On reaching Kingsdown this old thoroughfare veered left towards Bradford-on-Avon but its line there is completely obliterated by the Golf Course. On the side of the old road and near the Old Jockey are tumuli dated circa 500 BC. Maybe the mounds were the inspiration of the place-name of Hatt! Today only Hatt House and Hatt Farm perpetuate the old name.

Hatt House is on the site of an older building and until the early nineteenth century several small dwellings stood alongside the lane leading to the rear entrance. Except for Blue Vein farmhouse and one derelict cottage, these have disappeared. The lane at one time affording the only access to Hatt House leaves the old Ridgeway road by the turnpike cottage and, after passing the big house, continues downhill where it is called the Drilly. From here and through Box Bottoms it continues as a footpath to the village of Box. As the Drilly reaches the lower ground this old track is bisected by the A365, a road completed as late as 1840. Hatt Farm is of this same date. The house and buildings stand in a field and well back from the road. It is a half-mile from Hatt House. The new farmer took over the responsibility of cultivating all the Hatt fields which had been leased piecemeal for many years to local people. It is interesting to note that a 1630 map shows the land at Hatt divided into fields long before the enclosure Acts became law.

The Old Bath Road went past Chapel Plaister |

On the eastern boundary of the area two routes from London to Bath merged. One came via Devizes and the other through Lacock, Corsham and past the ancient pilgrim's rest called Chapel Plaister. Travellers from both roads were obliged to wind their way through Hatt, across Kingsdown Common and descend Bathford Hill to reach the city.

Packmen, drovers and merchants were among those who used the rough and rutted roads. Inns in towns and villages catered for folk making long weary journeys, and in rural areas refreshment was provided at ale-houses. In the early seventeenth century an ale-house was built at Hatt. Standing in a bend in the road, it was about half-way between the lane leading to Hatt House and the crossroads where the London roads met. |

It was built of local sandstone and roofed with thatch. A cobbled forecourt covered the ground between the road and the house: from this the entrance door opened directly into the ale-house kitchen. Heated by the fire in the ingle this room with its flagstone floor would have been used by both the family and customers. An extension at the rear of the main building, probably used as brew house and stable, completed this wayside tavern. In the right-angle formed by this L-shaped plan, stone steps once led down to the cellar that ran underneath the front part of the house. It is not known if it had a name but maybe it was called Cuff's Corner, as this particular bend in the road is so designated on some old maps.

|

The road to Bath coming past Chapel Plaister was turnpiked in 1713 and it continued as a main route to the city until the Rudloe-Box-Bath road was straightened and turnpiked about fifty years later. At Hatt a pike or gate was placed across the road near Blue Vein Farm. The gate-keeper's six-sided cottage stood alongside with its windows strategically sited to enable him to watch the road in either direction. The tolls collected at gates were used to mend the highways and the improved road surfaces encouraged more people to travel. The fashionable way to get from city to city was by stage-coach, and these picturesque but rather uncomfortable horse-drawn conveyances became a common sight on turnpiked roads.

Bath was fast becoming popular and consequently many more people used the roads leading to the city. Visitors were able to take the waters and enjoy social gatherings that were making Bath famous. |

So the old Ridgeway became part of one of the main coaching routes and the little ale-house at Hatt could not cope with the increase in its trade. In 1737 a larger establishment was built alongside. This new inn with Queen Anne proportions, a frontage of dressed stone, large windows and stone-tiled roof, completely dwarfed its humble neighbour. However a curtain wall was built linking the two buildings and this unusual feature contained an arched opening leading to the rear of both.

On either side of the archway false window mullions were superimposed, and into the upper part of the one on the right, a large flat stone was later inserted to serve as a porch to the present day entrance of the old ale-house. Variation in the stonework of the front wall shows that the original doorway was between the two front windows. The old and new hostelries probably traded as one. They were called The Horse and Jockey Inn.

The well at the back, first sunk to supply the older house with water, now boasted a high iron superstructure with cog-wheels and chains attached to iron-banded wooden buckets. By turning a handle one bucket could be lowered into the well as the other came up full of water. Rings for tethering horses were fixed into the front wall of the new inn, and a stone mounting-block placed at one side. Ample stabling was provided a few yards away.

Sleeping accommodation was available and the stairs to the bedrooms rose from the stone-floored hallway inside the rear entrance. On the wall at the foot of the stairs hung an iron bell with which, I assume, the landlord roused sluggish overnight visitors. From the same hall, stone steps descended to the cellar which ran under the entire building. Its stone floor and vaulted stone roof gave it the appearance of a church crypt. The strong arched ceiling supported the inn above without the addition of central pillars. Double doors at one end of the cellar opened on to the base of a flight of outside steps leading up to the inn-yard near to the wall. The steps were sheltered by the left-hand side of the curtain-wall joining the new inn and the old ale-house and the protection this provided to the steps and the cellar entrance could be the reason it was built.

On either side of the archway false window mullions were superimposed, and into the upper part of the one on the right, a large flat stone was later inserted to serve as a porch to the present day entrance of the old ale-house. Variation in the stonework of the front wall shows that the original doorway was between the two front windows. The old and new hostelries probably traded as one. They were called The Horse and Jockey Inn.

The well at the back, first sunk to supply the older house with water, now boasted a high iron superstructure with cog-wheels and chains attached to iron-banded wooden buckets. By turning a handle one bucket could be lowered into the well as the other came up full of water. Rings for tethering horses were fixed into the front wall of the new inn, and a stone mounting-block placed at one side. Ample stabling was provided a few yards away.

Sleeping accommodation was available and the stairs to the bedrooms rose from the stone-floored hallway inside the rear entrance. On the wall at the foot of the stairs hung an iron bell with which, I assume, the landlord roused sluggish overnight visitors. From the same hall, stone steps descended to the cellar which ran under the entire building. Its stone floor and vaulted stone roof gave it the appearance of a church crypt. The strong arched ceiling supported the inn above without the addition of central pillars. Double doors at one end of the cellar opened on to the base of a flight of outside steps leading up to the inn-yard near to the wall. The steps were sheltered by the left-hand side of the curtain-wall joining the new inn and the old ale-house and the protection this provided to the steps and the cellar entrance could be the reason it was built.

|

The new inn was indeed a very fine building and became popular with travellers and locals alike. In fact the Horse and Jockey became so well known that its name is used in a Turnpike Trust Act of 1753. This refers to the length of road as from Seend to the Horse and Jockey instead of from Seend to Hatt or Seend to Blue Vein in spite of the inn being some distance from the gate.

On the third Wednesday in September a sheep fair was held at Kingsdown. This was a busy time at the turnpike as animals were counted score by score, and the toll of five pence collected for every twenty before they could be driven through the gateway. Few people could count to more than twenty and a nick or score would be cut into a stick when this number was reached. Hence the word score became a synonym for twenty. On Kingsdown Fair Day, the road through Hatt was used more than usual, as without doubt there were booths and amusements as well as the sheep to attract crowds to the common. The Fair was sited on the left-hand side of the present road to Bath, and it continued to be held until the 1930s. The third Wednesday in September would bring extra trade to the Horse and Jockey. Many folk stopped there for rest and refreshment, and to discuss the price of sheep. |

The milestone that stood until 1939 by the Turnpike Cottage informed all who passed that they were 101 miles from London and six miles from Bath. It referred to the Chapel Plaister route used less after the road through Rudloe was improved. Travellers from the Devizes direction continued to use the road through Hatt, and a milestone standing by the inn referred to this route. They journeyed that way until Hatt was by-passed by a new road. This was cut from the cross-roads to the east through fields and woods to Box, where it met the road coming from Corsham. The roads merged and continued as one to Bath. Completed by 1840, this latest length of road enabled traffic to avoid the climb to Kingsdown and the steep descent to Bathford. Milestones were placed along this road and a new turnpike and gate-keeper's cottage erected where the road entered Box. Consequently the gate-keeper at Blue Vein had less to do and the amount of money colleted from the tolls dropped considerably. This was reflected in the deterioration of the road. Travellers to Bath preferred the new route, and thus the hey-day of Hatt and its inn was over. At this sad period of its history it became, with the exception of Blue Vein Farm, the property of the Fuller family of Neston Park in the next parish. The Horse and Jockey was obliged to close. It was let to a farmer who, with the now redundant inn stables and some fields at the rear of these buildings, developed a small-holding, eventually enlarged to become Old Jockey Farm.

|

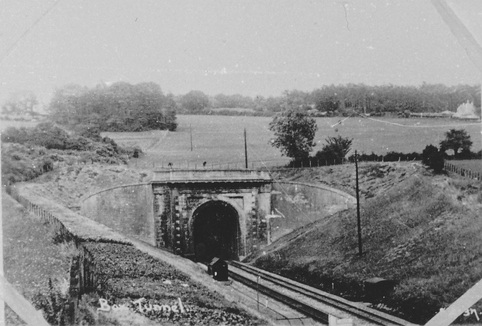

To serve the new road to Box an inn was built at the now five crossroads, and called the New Horse and Jockey. However this establishment had a shorter life than its namesake. The railway line from London to Bath was now completed and journeying between these cities was quicker by train than by road. The coaching era was coming to an end.

|

The Decline of the area called The Old Horse and Jockey |

Fortunately Hatt did not become a depressed area as the newly built Hatt Farm flourished, in spite of ceding some land to Old Jockey Farm and later to the farm at the crossroads. For many years it was occupied by the Pinchen family. Regrettably, after this date, Hatt gradually lost its identity. The houses near the turnpike became the hamlet of Blue Vein, taking this name from the nearby farm, and the gate-keeper's cottage became a farm-labourer's home. The old ale-house and its outbuildings were made into three small dwellings. The thatch on the roof was removed and replaced by slates. Shortly after this, the 1737 inn once so grand and important, was divided into two houses. The farmer living there since its closure, moved into a little house adjoining the farm buildings that were once the inn stables. It was of a later date than the inn and probably built to house an ostler during its hey-day.

All these hamlets were given a new postal address. The name Hatt was omitted, and everyone living in them found themselves in a hamlet called The Old Jockey, which was easier to say than The Old Horse and Jockey. The Old Jockey designation included an isolated cottage in the corner of a field. It had been converted from a field barn in 1801 and was reached by a footpath. To this day it is known as Jefferies Cottage, taking its name from the field in which it stands. Hatt Farm too became part of Old Jockey.

In the years preceding the Great War, Fullers enlarged the ostler's house at Old Jockey Farm. More fields were made available and new cowsheds and a dairy built. At Blue Vein the cottages beside the lane to Hatt House became empty and gradually crumbled away. The ruins of one still stand. It was occupied by a Hatt House gardener until the 1930s. Two cottages that stood immediately behind the turnpike were demolished ten years later. Thus Hatt faded from the map replaced by two hamlets, The Old Jockey and Blue Vein. No more entries in the Box Parish Register showed place of abode as Hatt. Hatt House fortunately retained the old name and was now approached by a new straight entrance drive through a gate half-way down Short Hill.

All these hamlets were given a new postal address. The name Hatt was omitted, and everyone living in them found themselves in a hamlet called The Old Jockey, which was easier to say than The Old Horse and Jockey. The Old Jockey designation included an isolated cottage in the corner of a field. It had been converted from a field barn in 1801 and was reached by a footpath. To this day it is known as Jefferies Cottage, taking its name from the field in which it stands. Hatt Farm too became part of Old Jockey.

In the years preceding the Great War, Fullers enlarged the ostler's house at Old Jockey Farm. More fields were made available and new cowsheds and a dairy built. At Blue Vein the cottages beside the lane to Hatt House became empty and gradually crumbled away. The ruins of one still stand. It was occupied by a Hatt House gardener until the 1930s. Two cottages that stood immediately behind the turnpike were demolished ten years later. Thus Hatt faded from the map replaced by two hamlets, The Old Jockey and Blue Vein. No more entries in the Box Parish Register showed place of abode as Hatt. Hatt House fortunately retained the old name and was now approached by a new straight entrance drive through a gate half-way down Short Hill.

|

Short Hill, though very steep, links the Old Jockey with Chapel Plaister, and is as old as the Ridgeway with which it connects at either end. In dry weather it was probably used as a short cut in 500 BC. Similarly used throughout the centuries it is obvious how it came by its name. The 1840 road to Box crossed Short Hill at the lowest point. This was raised to the level of the new thoroughfare, and no longer did a muddy hollow have to be negotiated before the steep rise to Chapel Plaister.

The land behind the converted Old Jockey buildings was divided into allotment-like gardens for the tenants. The garden spread around two sides of the old ale-house, covering almost all the pitching stones paving its forecourt. Grass grew over the open space in front of the once stately Horse and Jockey. By converting the inn and ale-house into smaller units, the Fullers of Neston Park certainly did their best to revitalise the hamlet and they kept the property well maintained. After many years of ownership they installed a pump to supply their tenants with drinking water. It was situated by the gate into Old Jockey Farm and fetching water from the pump was far less arduous than drawing it from the well, hitherto the only source. |

Much, much later, mains water reached Old Jockey house but in 1949, before this improvement, Neston Park sold the houses in the hamlet, retaining only the two farms. However thirty years later Old Jockey Farm house changed hands to become a private residence. Its fields have been returned to Hatt Farm which remains part of the Estate. The other holder of the old name, Hatt House, had been sold in the 1920s to Miss Doris Chappell who lived in it for a further fifty years. The 1737 inn is again one house and some of its original features have been uncovered and carefully restored by the present owners. Two of the smaller dwellings at The Old Jockey have been enlarged. The hamlet is changing once more.

Chapter 1 Settling Down [1]

On demobilisation from serving in the First World War, my father returned to work for the Fuller family of Neston where he had been employed as Estate carpenter prior to joining the Royal Engineers.

Now married with a baby daughter he needed a house and the first to become vacant on the Estate happened to be in the hamlet on the outskirts of the village of Box, known as The Old Jockey. So my parents and I, for I was that little girl, left the house we had been sharing with my paternal grandparents in the village and moved into our first real home. Of the event I remember nothing.

The Old Jockey is situated on rising ground alongside an old coaching road to Bath, at the junction with Short Hill. It was down this hill we went to reach the village two miles away. My father's daily cycle ride to Neston Park was about the same distance but this was in the opposite direction.

The hamlet I was to come to know so well was comprised of two farms and six smaller dwellings. One of these was completely isolated and only reached by a path through a field. The others, two converted from an eighteenth century inn and three made from an even older ale-house, were on the roadside. Our little home was actually the front part of the ale-house. Its forecourt had been walled round and made into a garden. The garden continued round the furthermost end of our house to join at the back with the garden of our neighbours. These plots were only separated by earthen paths but dry-stone walls bounded them. Thus they were protected from cattle in the fields of Old Jockey Farm and Hatt Farm. Old Jockey Farm was close to us whilst Hatt Farm stood a field away at the end of a rough track. A big white gate opening onto the track was attached to our front garden wall. The gate was also used by the occupants of the isolated house in the field.

The entrance doors to the three dwellings made from the old ale-house each opened directly into the larger of the two ground-floor rooms. Fitted with black oven grates these rooms were intended to be used as kitchens. In each inner room there were the low barred grates usual in parlours or front rooms in Victoria times. It was a most inconvenient arrangement.

On demobilisation from serving in the First World War, my father returned to work for the Fuller family of Neston where he had been employed as Estate carpenter prior to joining the Royal Engineers.

Now married with a baby daughter he needed a house and the first to become vacant on the Estate happened to be in the hamlet on the outskirts of the village of Box, known as The Old Jockey. So my parents and I, for I was that little girl, left the house we had been sharing with my paternal grandparents in the village and moved into our first real home. Of the event I remember nothing.

The Old Jockey is situated on rising ground alongside an old coaching road to Bath, at the junction with Short Hill. It was down this hill we went to reach the village two miles away. My father's daily cycle ride to Neston Park was about the same distance but this was in the opposite direction.

The hamlet I was to come to know so well was comprised of two farms and six smaller dwellings. One of these was completely isolated and only reached by a path through a field. The others, two converted from an eighteenth century inn and three made from an even older ale-house, were on the roadside. Our little home was actually the front part of the ale-house. Its forecourt had been walled round and made into a garden. The garden continued round the furthermost end of our house to join at the back with the garden of our neighbours. These plots were only separated by earthen paths but dry-stone walls bounded them. Thus they were protected from cattle in the fields of Old Jockey Farm and Hatt Farm. Old Jockey Farm was close to us whilst Hatt Farm stood a field away at the end of a rough track. A big white gate opening onto the track was attached to our front garden wall. The gate was also used by the occupants of the isolated house in the field.

The entrance doors to the three dwellings made from the old ale-house each opened directly into the larger of the two ground-floor rooms. Fitted with black oven grates these rooms were intended to be used as kitchens. In each inner room there were the low barred grates usual in parlours or front rooms in Victoria times. It was a most inconvenient arrangement.

|

This layout was a modification of medieval Manor House planning, where the main room, the hall, was used for cooking, eating and in some cases sleeping. Leading from this would be a solar or store or both.

|

Modification of our medieval Manor House |

In humbler homes the hall became the kitchen and like the early manor houses, it would contain the entrance door, an open fireplace and, if there were upper rooms, a staircase winding upwards at one side of the chimney-breast. Leading from this room would be a pantry or as at The Old Jockey, a parlour. While manor houses became larger and grander it took hundreds of years for the landlords of rural properties to improve on the old plan for the lower classes, so when the ale-house was divided into three units in the mid nineteenth century it was still considered that the occupants would need nothing different. Except that is, an oven-grate instead of an open fire.

However my mother decided to use our inner room as her kitchen. There my father erected shelves for china and in one corner a wide wooden ledge for the enamel washing-up bowl and the tin draining tray. The low parlour-grate was completely ignored. So the larger room became our living room and in spite of the black range and the outside door, it was cosy and very comfortable.

Our door was not the original entrance. That had been at the centre front between the windows and from outside its position could be seen by a variation in the stonework. Inside, shelves marked the spot. The doorway had been filled in as thick as the old wall half-way up. The infill at the top was less and left a recess in which were the shelves. The later door was situated on the end of the house and opened at one side of the enormous chimney-breast. It would have been here by the fireplace that the original stairs or maybe only a ladder leading to the bedrooms would have stood. Our staircase covered by a wooden partition was approached by a door in the back room.

In the old days the larger room, the kitchen of the ale-house, would have been used by both family and customers sharing the warmth of the fire. Hollows in the stone-flagged floor show where countless ale drinkers had scuffed their boots while sitting on benches under the walls. Other features of the old days remained, such as cupboards built into the thickness of the walls, the heavy beam to support the upper floor and the cellar running underneath our house and under our next-door neighbour's larger room. At one time the cellar would have been entered by stone steps from the yard at the back of the house. By the time we arrived at The Old Jockey, the only remaining entrance was through a trap-door in the floor of our inner room, the kitchen. After a futile attempt to grow rhubarb in the hard earth that formed its base my father sealed the trap-door and never during my childhood did I have the opportunity to explore the dark, empty hole under the two houses.

Our windows had stone mullions and on the lower edge of one the sill was worn down into a curve. This was thought to be where many a knife had been sharpened on the stone. Below each window were seats cut out of the wall providing extra accommodation for callers in those old days.

However my mother decided to use our inner room as her kitchen. There my father erected shelves for china and in one corner a wide wooden ledge for the enamel washing-up bowl and the tin draining tray. The low parlour-grate was completely ignored. So the larger room became our living room and in spite of the black range and the outside door, it was cosy and very comfortable.

Our door was not the original entrance. That had been at the centre front between the windows and from outside its position could be seen by a variation in the stonework. Inside, shelves marked the spot. The doorway had been filled in as thick as the old wall half-way up. The infill at the top was less and left a recess in which were the shelves. The later door was situated on the end of the house and opened at one side of the enormous chimney-breast. It would have been here by the fireplace that the original stairs or maybe only a ladder leading to the bedrooms would have stood. Our staircase covered by a wooden partition was approached by a door in the back room.

In the old days the larger room, the kitchen of the ale-house, would have been used by both family and customers sharing the warmth of the fire. Hollows in the stone-flagged floor show where countless ale drinkers had scuffed their boots while sitting on benches under the walls. Other features of the old days remained, such as cupboards built into the thickness of the walls, the heavy beam to support the upper floor and the cellar running underneath our house and under our next-door neighbour's larger room. At one time the cellar would have been entered by stone steps from the yard at the back of the house. By the time we arrived at The Old Jockey, the only remaining entrance was through a trap-door in the floor of our inner room, the kitchen. After a futile attempt to grow rhubarb in the hard earth that formed its base my father sealed the trap-door and never during my childhood did I have the opportunity to explore the dark, empty hole under the two houses.

Our windows had stone mullions and on the lower edge of one the sill was worn down into a curve. This was thought to be where many a knife had been sharpened on the stone. Below each window were seats cut out of the wall providing extra accommodation for callers in those old days.

|

On our arrival, living conditions were little better than when our home was an open house, for The Old Jockey had no gas, electricity or mains water. We obtained our water from a communal pump by the front gate of Old Jockey Farm. Previous to the installation of the pump, I was told that the well in the yard behind the inn was the only source of supply. But at least once a year the pump ran dry and we had to resort to using the well again.

At these times of crisis Neston Estate sent along Mr Merrett with a traction engine; not to our pump, but to the storage tank buried in a field at the bottom of Short Hill. Here in a small stone building covering the tank was housed an engine to supply the power to force water up the hill to use. Mr Merrett linked this mechanism to the powerful traction engine with endless belts and eventually it started and our supply was restored. To save journeys to the pump every household collected rain-water in wooden barrels or butts as they were often called, and this was used for washing ourselves and our clothes. It was considered ideal for these purposes as it was soft. Pump water and rain water were kept indoors in buckets and dipped from these with a jug. |

My mother reserved an old bucket for used water, and emptied the contents into a trench in the garden. Every so often my father filled in one trench and dug another for the disposal of household waste, for we had no refuse collection or drains at The Old Jockey.

A wash-house had been built onto each house and to reach ours we went outside and along the path under the window. Inside stood a stone copper for boiling water on wash-days and to one side of it we kept our coal. On the other side in the darkest corner was our lavatory - an earth closet. This was emptied from the outside where low down in the wall was a sliding door - a wooden shutter as seen today on coal bunkers. The contents were shovelled out once a week and buried in the garden. It was a very unpleasant job for the man of the house. The closets of our neighbours were purpose-built in a block of four just where their gardens began. They worked on the same principle but being outside were lighter and appeared to be more hygienic.

A wash-house had been built onto each house and to reach ours we went outside and along the path under the window. Inside stood a stone copper for boiling water on wash-days and to one side of it we kept our coal. On the other side in the darkest corner was our lavatory - an earth closet. This was emptied from the outside where low down in the wall was a sliding door - a wooden shutter as seen today on coal bunkers. The contents were shovelled out once a week and buried in the garden. It was a very unpleasant job for the man of the house. The closets of our neighbours were purpose-built in a block of four just where their gardens began. They worked on the same principle but being outside were lighter and appeared to be more hygienic.

New loos for The Old Jockey |

While we were living at The Old Jockey, Neston Estate decided to 'modernise' and provided each closet with a wide topped bucket that could be removed by side handles from under the front seat. The front panels had to be removed to facilitate this. The contents were disposed of in the garden as before but the procedure was quicker and cleaner.

|

Laundry was always attended to on Mondays. The stone copper would be filled with rain-water and a fire lit in the small oven-like cavity underneath. The water took a long time to get hot and when it did, some was ladled out into a galvanised bath standing on a washing-stool. This was a long narrow table just wide enough to hold the bath. In this bath the clothes and linen were washed. All the white articles were then transferred to the copper where soda had been dissolved in the now boiling water, and stirred around with a copper stick. This was usually part of a broom handle. Every item was later lifted out with the aid of this stick and then rinsed in cold rain-water in another bath. After being wrung by hand the clean things were pegged on lines in the garden to dry in the fresh air. There were no detergents then, only Sunlight soap and soda until Rinso and Lux came along. Whiteness was ensured by the use of the blue-bag in a second rinse.

Tablecloths, men's collars, aprons and many other articles were starched and when dry needed to be liberally sprinkled with water in order to be ironed satisfactorily. Flat irons were heated on a trivet in front of the fire in the black range. Two irons were necessary so that one could be in use whilst the other got hot, and so able to be changed over quite often. The heat was tested by dabbing some saliva onto the iron. If it sizzled the iron was ready.

Tablecloths, men's collars, aprons and many other articles were starched and when dry needed to be liberally sprinkled with water in order to be ironed satisfactorily. Flat irons were heated on a trivet in front of the fire in the black range. Two irons were necessary so that one could be in use whilst the other got hot, and so able to be changed over quite often. The heat was tested by dabbing some saliva onto the iron. If it sizzled the iron was ready.

|

Housework was hard for women in rural areas. My mother was already thirty-six when she married and had for some years held senior positions in houses of wealthy families. She had been used to turning taps and switching on electric light and she told me she often cried when we first moved into our inconvenient little house. Coping with the laundry was fraught with difficulties and so was cooking on the range. Apparently the first time mother attempted to make jam on the open fire beside the oven the saucepan tipped over, spilling the jam over the bars and onto the coals. The mess and smell must have been heart-breaking. Even if a kettle boiled over the fire, the smell was most unpleasant, and the fire was likely to be put out too.

|

As the years passed, mother mastered wash-days, the oil-lamps and our little oil-stove, but never the black range. Knowing no other home, I took the conditions for granted and only later came to realise the difficulties my parents had to overcome. However they did what they could to improve matters.

It was at the time of the 1926 General Strike that they bought our big oil-stove, as coal was becoming hard to come by. Mother found this cooker of great benefit for years afterwards. Everyone at The Old Jockey possessed a small oil-stove useful for boiling a kettle or saucepan, but the big one made by Rippengale had an oven. This was heated underneath by two burners and on top of the oven were two round grills where saucepans could be heated at the same time. The Rippengale stood on a large wooden stand placed in the hearth of the unused parlour grate in our kitchen.

Next the problem of bathing was solved by the purchase of a long galvanised bungalow bath. It was kept in the wash-house. As water was too precious to be wasted, we bathed on Monday evenings. More water would be added to that remaining in the copper and the fire underneath rekindled. With buckets of rain water ready for cooling and the door of the cavity containing the embers open to let the warmth escape, bathing in the wash-house was reasonably comfortable. As a small child I was bathed indoors in a washing bath in front of the fire and it was also in front of the fire my long hair was dried on shampoo nights. Maybe shampoo is the wrong word as mother insisted on washing my hair with Wrights Coal Tar Soap. When dry, mother singed the ends of my tresses with a lighted taper to prevent them from becoming straggly.

It was at the time of the 1926 General Strike that they bought our big oil-stove, as coal was becoming hard to come by. Mother found this cooker of great benefit for years afterwards. Everyone at The Old Jockey possessed a small oil-stove useful for boiling a kettle or saucepan, but the big one made by Rippengale had an oven. This was heated underneath by two burners and on top of the oven were two round grills where saucepans could be heated at the same time. The Rippengale stood on a large wooden stand placed in the hearth of the unused parlour grate in our kitchen.

Next the problem of bathing was solved by the purchase of a long galvanised bungalow bath. It was kept in the wash-house. As water was too precious to be wasted, we bathed on Monday evenings. More water would be added to that remaining in the copper and the fire underneath rekindled. With buckets of rain water ready for cooling and the door of the cavity containing the embers open to let the warmth escape, bathing in the wash-house was reasonably comfortable. As a small child I was bathed indoors in a washing bath in front of the fire and it was also in front of the fire my long hair was dried on shampoo nights. Maybe shampoo is the wrong word as mother insisted on washing my hair with Wrights Coal Tar Soap. When dry, mother singed the ends of my tresses with a lighted taper to prevent them from becoming straggly.

My first bathroom |

I was eleven years old before I used a bath in a bathroom. It was during a visit to my aunt and uncle in London and although I had seen a bath before I was truly scared when told to step into this big white thing with hot water gushing into it from a brass tap. The water covered so much more of me than the two or three bucketsful dipped from the copper at home.

|

The next modern convenience invested in by our family was an Acme wringer. Laundry squeezed between its rubber rollers dried so much quicker than before. The procedure was simple and more efficient, making wash-day easier.

Soon afterwards we had a Primus stove. Methylated spirits were needed to start it burning, but after pumping with a little brass handle for a few seconds the paraffin took over and this produced a fierce heat. The Primus eliminated the necessity of lighting the fire in the summer for the sole purpose of heating the flat-irons. They still needed to be rubbed over with a duster before use.

Our garden was the only one at The Old Jockey without an old pigsty, and as none of the neighbours kept pigs, they were able to utilise these as garden sheds. My father built all the sheds we needed, and we soon had one in which to store the paraffin, one to shelter his hand-made wooden wheelbarrow, a house and run for our hens, and a carpenter's shop. My father retreated to this workshop on winter evenings and by the light of a hurricane lamp did repairs to neighbours' furniture and occasionally made small tables and cupboards for our house. He actually made my first bed. Making such pieces gave my father the opportunity to practise his craft of cabinet making and joinery which he had little chance to pursue on the Neston Estate.

The Old Jockey gardens were well cared for and I do not remember any unsightly heaps of rubbish. All waste was buried or burnt. Empty cocoa or mustard tins proved useful for storing nails and screws, and as my mother was reluctant to use tinned food, we had little refuse of that kind. I do not recall how we disposed of empty bottles. They were probably smashed and buried in an odd corner.

My father worked long hours at Nest Park Estate and his only free time was on Saturday afternoons, Sundays and Bank Holidays. Like other men at The Old Jockey he tilled his garden and an allotment. The allotments, one for each household, were in a corner of a field next to Jefferies Cottage. They were approached through a field belonging to Old Jockey Farm, and not by the path to the cottage. My mother made a delightful flower garden in front of our windows and for most of the year it was gay with colour. She loved making rockeries and crazy paving paths although I regret to say, she stole the stones, one by one, from the walls that bounded the fields round about.

So we settle down in our little house, accepting the inconveniences and making the most of the countryside on our doorstep. Ever hopeful of renting a larger house, my parents did not find one for some years. I spent all my childhood at The Old Jockey, the hamlet at the top of Short Hill.

Soon afterwards we had a Primus stove. Methylated spirits were needed to start it burning, but after pumping with a little brass handle for a few seconds the paraffin took over and this produced a fierce heat. The Primus eliminated the necessity of lighting the fire in the summer for the sole purpose of heating the flat-irons. They still needed to be rubbed over with a duster before use.

Our garden was the only one at The Old Jockey without an old pigsty, and as none of the neighbours kept pigs, they were able to utilise these as garden sheds. My father built all the sheds we needed, and we soon had one in which to store the paraffin, one to shelter his hand-made wooden wheelbarrow, a house and run for our hens, and a carpenter's shop. My father retreated to this workshop on winter evenings and by the light of a hurricane lamp did repairs to neighbours' furniture and occasionally made small tables and cupboards for our house. He actually made my first bed. Making such pieces gave my father the opportunity to practise his craft of cabinet making and joinery which he had little chance to pursue on the Neston Estate.

The Old Jockey gardens were well cared for and I do not remember any unsightly heaps of rubbish. All waste was buried or burnt. Empty cocoa or mustard tins proved useful for storing nails and screws, and as my mother was reluctant to use tinned food, we had little refuse of that kind. I do not recall how we disposed of empty bottles. They were probably smashed and buried in an odd corner.

My father worked long hours at Nest Park Estate and his only free time was on Saturday afternoons, Sundays and Bank Holidays. Like other men at The Old Jockey he tilled his garden and an allotment. The allotments, one for each household, were in a corner of a field next to Jefferies Cottage. They were approached through a field belonging to Old Jockey Farm, and not by the path to the cottage. My mother made a delightful flower garden in front of our windows and for most of the year it was gay with colour. She loved making rockeries and crazy paving paths although I regret to say, she stole the stones, one by one, from the walls that bounded the fields round about.

So we settle down in our little house, accepting the inconveniences and making the most of the countryside on our doorstep. Ever hopeful of renting a larger house, my parents did not find one for some years. I spent all my childhood at The Old Jockey, the hamlet at the top of Short Hill.

Chapter 2 And They Came to the Door

|

Writing about The Old Jockey has brought to mind the various tradesmen who called to supply our needs. Mr Davis, known as the oil-man, came every Tuesday and from him we bought paraffin for the lamps and oil-stoves. The paraffin tank took up most of the space in Mr Davis' big van but there was sufficient room left for buckets, brushes, enamel bowls and jugs, and galvanised baths. Some of the items were carried on the roof of the van, and some in fixtures on the sides. An excellent way to advertise these wares.

Coal was delivered in sacks by lorry as it is today but wood purchased from the Neston Estate arrived on a horse-drawn wagon. |

The baker, Mr Brooks and later Mr Wilkins, called daily with bread. It was freshly baked each morning in the bake-house adjoining the general shop and Post Office at Kingsdown. On Good Fridays Hot Cross buns were still hot from the oven when they reached us. No bread was sold that day. I can just remember Mr Brooks using an enclosed horse-drawn bread cart. It had a curved roof and doors at the back.

On Wednesdays and Saturdays a Mr Hayward from Bath would arrive selling fish and fruit from a long flat wagon. While purchases were made, his horse enjoyed nibbling the grass growing on the open space in front of the old inn. The fish was chiefly of the smoked variety but he did bring fresh herrings.

Meat was delivered by the Box butcher, but had to be ordered. Groceries could be obtained in the same way from Bence's and later from the Co-op, the two largest shops in the village. The butcher used a van, but groceries were brought by the shops' errand-boy riding a bicycle with a large metal carrier basket in front for the goods. Under the bar of the bike a flat metal plate advertised the shop's name and trade. Newspapers were taken round by a boy riding a similar machine but the postman came on foot. There were no letter boxes on doors at The Old Jockey, so both had to knock.

On Wednesdays and Saturdays a Mr Hayward from Bath would arrive selling fish and fruit from a long flat wagon. While purchases were made, his horse enjoyed nibbling the grass growing on the open space in front of the old inn. The fish was chiefly of the smoked variety but he did bring fresh herrings.

Meat was delivered by the Box butcher, but had to be ordered. Groceries could be obtained in the same way from Bence's and later from the Co-op, the two largest shops in the village. The butcher used a van, but groceries were brought by the shops' errand-boy riding a bicycle with a large metal carrier basket in front for the goods. Under the bar of the bike a flat metal plate advertised the shop's name and trade. Newspapers were taken round by a boy riding a similar machine but the postman came on foot. There were no letter boxes on doors at The Old Jockey, so both had to knock.

|

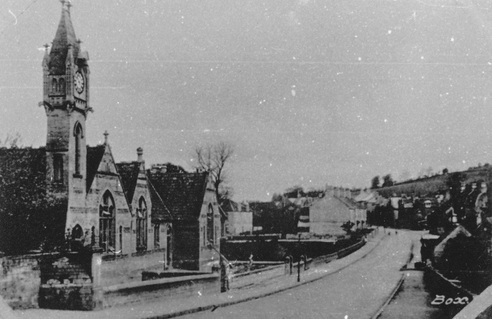

Our postman, Mr Ford, always gave a cheery greeting with the mail and he could be relied upon to know the right time. This was a welcome way to check the clocks in pre-radio days. It was possible to hear the hours strike on Box School clock, but only if the wind was in the right direction. Occasionally a man would call at the hamlet selling china. He carried it on a flat wagon similar to the one used by the fish-man and all the items were buried in straw to prevent breakages. While the horse enjoyed eating the grass the housewives gathered round examining the wares and usually they would make a purchase. No doubt the china was seconds but my mother did buy some very good Delft and Ironstone pieces from this hawker.

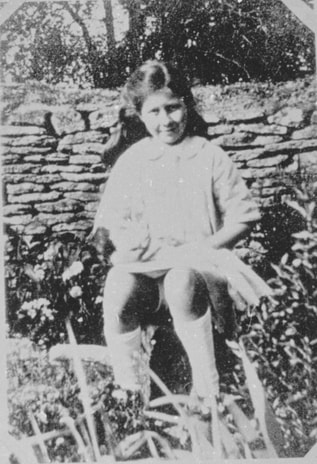

Photographers called at houses in the 1920s offering to take pictures of children or to enlarge photographs already in possession of the family. Some were rogues who took the money and failed to return with the developed picture, but I have one of myself aged three taken by one of these entrepreneurs, so they were not all bad. Other tradesmen one had to be wary of were those selling linoleum and rugs. My mother did buy some linoleum from one of them. She grumbled about the price but years later when it was still in good condition decided that she had not done too badly after all, although she continued to wonder if the hawker had come by the floor covering honestly. |

One other salesman came from time to time offering clothes and household linens. He was not patronised by my mother as she preferred to buy such things from the Bath shops. Being a good needlewoman she often bought material by the yard and made dresses and underwear for herself and for me. Mother also made my father shirts and collars from strong white cotton twill with either a brown or blue stripe on a white background. This fabric was called shirting. Socks, gloves, scarves, jerseys and my tam-o-shanters were all knitted by my mother. By her industry the three of us were always well clothed. Perhaps I should include our gypsy callers among those who supplied our needs at The Old Jockey. They sold clothes-pegs made from saplings whittled into shape at their encampment on Wadswick Common.

Being so close to Old Jockey Farm every household fetched their supply of milk in jugs from the dairy there. Mrs Clark, the wife of the farmer, also sold eggs, chickens and tasty home-made faggots. Going to the farm to make a purchase was a pleasant diversion. Having large gardens and allotments, all vegetables were home-grown. Every garden contained plums and apple trees, gooseberry and currant bushes, together with a root of rhubarb. These could be supplemented by blackberries, gathered from the hedgerows in the autumn, so consequently there was no need to buy fruit for pies or jam.

The potatoes needed for use during the winter were stored outside in a clamp. First a hollow had to be dug in the garden and this was lined with straw. The potatoes were piled on top of this and covered with more straw, wigwam fashion. The resulting mound was protected from the winter weather by soil. The clamp would be uncovered as the potatoes were required and carefully re-sealed. This process continued until all were used and the clamp dismantled.

We kept seven or eight hens to supply us with eggs. Potato peelings boiled and mixed with bran helped to feed them. It was necessary to buy maize for them and broken shells mixed with their food ensured the hens laid eggs with hard coverings. And so most of our needs were supplied. Some required an effort on our part while some needed no effort at all.

One of our neighbours, Mrs Bird, who lived in part of the old inn carried on a business of her own selling biscuits and soft drinks. Then for a short time my parents supplemented their income by selling cigarettes, tobacco and matches. Being so far from the village this was appreciated by the local men who all smoked in those days. Seeing the advertisement on our door, complete strangers called too and this made my mother feel nervous if she was alone at the time and so the venture ended.

Being so close to Old Jockey Farm every household fetched their supply of milk in jugs from the dairy there. Mrs Clark, the wife of the farmer, also sold eggs, chickens and tasty home-made faggots. Going to the farm to make a purchase was a pleasant diversion. Having large gardens and allotments, all vegetables were home-grown. Every garden contained plums and apple trees, gooseberry and currant bushes, together with a root of rhubarb. These could be supplemented by blackberries, gathered from the hedgerows in the autumn, so consequently there was no need to buy fruit for pies or jam.

The potatoes needed for use during the winter were stored outside in a clamp. First a hollow had to be dug in the garden and this was lined with straw. The potatoes were piled on top of this and covered with more straw, wigwam fashion. The resulting mound was protected from the winter weather by soil. The clamp would be uncovered as the potatoes were required and carefully re-sealed. This process continued until all were used and the clamp dismantled.

We kept seven or eight hens to supply us with eggs. Potato peelings boiled and mixed with bran helped to feed them. It was necessary to buy maize for them and broken shells mixed with their food ensured the hens laid eggs with hard coverings. And so most of our needs were supplied. Some required an effort on our part while some needed no effort at all.

One of our neighbours, Mrs Bird, who lived in part of the old inn carried on a business of her own selling biscuits and soft drinks. Then for a short time my parents supplemented their income by selling cigarettes, tobacco and matches. Being so far from the village this was appreciated by the local men who all smoked in those days. Seeing the advertisement on our door, complete strangers called too and this made my mother feel nervous if she was alone at the time and so the venture ended.

The Old Jockey became |

While it lasted, The Old Jockey became a miniature shopping centre. For there could be purchased cigarettes, biscuits, lemonade, milk, eggs, chickens and Mrs Clark's faggots. In spite of the self-sufficiency practised in the hamlet and the regular deliveries of day-to-day requirements, my mother enjoyed visiting the Bath shops.

|

The city was not easy to reach when we moved to The Old Jockey. One either had to walk to Box Station and go by train or to walk to Bathford and take a tram from the terminus there. Mother chose the latter and apparently pushed me in my pram across Kingsdown and down Bathford Hill to a house where prams and bicycles could be left until the tram brought us back. Shopping with a toddler could not have been easy and after the return tram ride it was a long climb up to Kingsdown. On reaching Gridiron Farm the walk became easier as it was downhill for the rest of the journey home.

Fortunately buses soon began to run from Devizes to Bath, passing along the main road at the bottom of Short Hill. By walking there to catch the bus we could ride all the way to the Parade at Bath. As all these buses passed through Box they could be used to get to shops, friends and to the doctor in the village too.

With no telephone at The Old Jockey a doctor could only be summoned by someone calling at his house and leaving a message with the maid who answered the door. Our doctor, Dr Martin, visited his patients on horse-back. When calling on The Old Jockey folks he always used one of the tethering rings on the old inn to tie his horse.

We were a reasonably fit community but from time to time did require medical aid. If medicine was prescribed another journey to the doctor's house had to be undertaken by a neighbour or relative to collect the potion. The surgery and dispensary were both in this house and in the wall dividing them from the waiting room a shutter in a hatch-way was raised by the doctor who called Next please. Medicine was made up by a lady dispenser and when ready was passed through the same opening. Pills or tablets were rarely prescribed and so most medicines had to be bottled. All bottles were wrapped in paper and this was sealed top and bottom with red wax. Medicines were wrapped in white paper for paying patients and in newspaper for club patients.

By paying a few pence weekly to a sick benefit society, and one called The Pioneers comes to mind, a member became entitled to free medical attention. When the breadwinner, the husband, was ill and unable to work, he also received a small regular payment from the club. My parents subscribed to a Nursing Association and by doing so, I believe, we were entitled to free care from the Box District Nurse.

This dedicated lady ministered to the sick, elderly and the injured in the parish, and to reach these in outlying areas she used a bicycle. After I had a particularly bad tumble the nurse came daily to our home at The Old Jockey to attend to my injured knee.

Bicycles were a popular means of transport and many people relied on pedal power to travel to work. The village policeman used a bike to patrol the parish and telegrams were delivered by a boy riding one of these machines. So by various means (bike, horse, horse and wagon, van, lorry and Shank's pony) provisions, household goods and medical aid came to my childhood home.

There were occasions when answering a knock on the door one found a tramp standing outside. Called old tramps by virtue of their unshaven faces, these vagrants walked from workhouse to workhouse begging for food on the way. My mother never refused to brew them tea in the old cocoa-tins they used as both tea-pot and cup, and she fed them on bread and cheese. These men called so often that we thought there must be a secret sign on our wall to guide members of their fraternity to our house.

Fortunately buses soon began to run from Devizes to Bath, passing along the main road at the bottom of Short Hill. By walking there to catch the bus we could ride all the way to the Parade at Bath. As all these buses passed through Box they could be used to get to shops, friends and to the doctor in the village too.

With no telephone at The Old Jockey a doctor could only be summoned by someone calling at his house and leaving a message with the maid who answered the door. Our doctor, Dr Martin, visited his patients on horse-back. When calling on The Old Jockey folks he always used one of the tethering rings on the old inn to tie his horse.

We were a reasonably fit community but from time to time did require medical aid. If medicine was prescribed another journey to the doctor's house had to be undertaken by a neighbour or relative to collect the potion. The surgery and dispensary were both in this house and in the wall dividing them from the waiting room a shutter in a hatch-way was raised by the doctor who called Next please. Medicine was made up by a lady dispenser and when ready was passed through the same opening. Pills or tablets were rarely prescribed and so most medicines had to be bottled. All bottles were wrapped in paper and this was sealed top and bottom with red wax. Medicines were wrapped in white paper for paying patients and in newspaper for club patients.

By paying a few pence weekly to a sick benefit society, and one called The Pioneers comes to mind, a member became entitled to free medical attention. When the breadwinner, the husband, was ill and unable to work, he also received a small regular payment from the club. My parents subscribed to a Nursing Association and by doing so, I believe, we were entitled to free care from the Box District Nurse.

This dedicated lady ministered to the sick, elderly and the injured in the parish, and to reach these in outlying areas she used a bicycle. After I had a particularly bad tumble the nurse came daily to our home at The Old Jockey to attend to my injured knee.

Bicycles were a popular means of transport and many people relied on pedal power to travel to work. The village policeman used a bike to patrol the parish and telegrams were delivered by a boy riding one of these machines. So by various means (bike, horse, horse and wagon, van, lorry and Shank's pony) provisions, household goods and medical aid came to my childhood home.

There were occasions when answering a knock on the door one found a tramp standing outside. Called old tramps by virtue of their unshaven faces, these vagrants walked from workhouse to workhouse begging for food on the way. My mother never refused to brew them tea in the old cocoa-tins they used as both tea-pot and cup, and she fed them on bread and cheese. These men called so often that we thought there must be a secret sign on our wall to guide members of their fraternity to our house.

|

In winter we were forced to amuse ourselves in the house or barn or in one of the sheds. Sometimes we helped to cut up mangolds and swedes for the cows to eat when there was no grass. Cattle-cake, a manufactured winter-feed needed to be cut in small pieces too.

One day Walter, the youngest of the three Clark children, was playing with the cutting machine and cut off the top of one of his fingers. I was in my own garden at the time, but so clearly heard his scream. Another lesson was learnt - leave machines alone ! |

If snow came we took Walter's home-made sledge to the steep field that was reached by crossing the main road at the bottom of Short Hill. Sliding was popular too. The roads would become slippery as the snow on them was pressed down and after sliding repeatedly over a stretch of a few feet, the surface shone like glass and became ideal for our purpose. Nevertheless our slides were dangerous for unwary pedestrians. Not all the roads around The Old Jockey boasted a footpath. But normally that did not matter as then there were very few cars about.

However winter turned to spring. The celandines and violets peeped out between the dead leaves under the hedges and walls, and birds built new nests. Rooks nested high in the many elms and beech trees which bordered the fields; even now, years later, if I hear the cawing of rooks, I am immediately reminded of The Old Jockey where the sound was so familiar.

Searching for nests in the hedgerow was a regular pastime every spring. Girls didn't steal the eggs but boys did. Perhaps just one from a nest, but another might be taken by a pilferer, and so on till the nest was empty, and the mother bird left bewildered and forlorn. By piercing an egg at both ends with a pin, the yolk could be blown out and the shell added to a treasured collection.

Robins often built their nests in the bank on the side of Short Hill but neither boys nor girls would steal their eggs. It was said that the fingers of the hand that picked up a robin's egg would for ever be fixed in that bent position.

With the arrival of spring the farm became our Mecca once more. New calves and baby chicks were arriving daily. The swing was fixed up in the old apple tree again, and in swinging high on it our feet touched its gnarled branches. Dolly, the eldest of the Clarks, often gave me rides on the carrier of her bike, and much later I learnt to balance on that same bike, after it had been handed down to Vi and then to Walter.

At haymaking time we would all take sandwiches to the hayfield and eat them in a house made of hay. Afterwards we were happy to follow the loaded wagons back to the farm, where the ricks were being made, just to have a ride back to the field when they returned empty to be loaded once more.

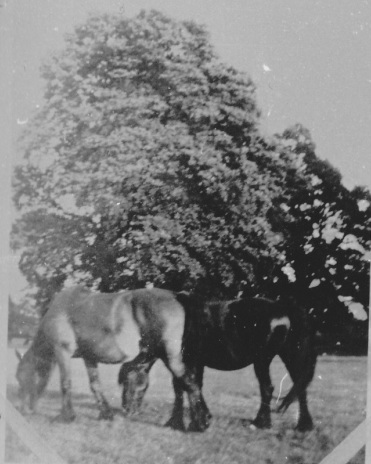

Wagons, mowing machines, tosser and rake were all pulled by horses and Captain, one horse, was a soldier for he had served in the Great War. Dumpling, as the name implies, was a chubby comfortable sort of horse, who plodded along quite happily beside his more athletic stable-mate. Witty and Tommy took turns drawing the milk-float. Milking was accomplished by hand and the milkers sat on three-legged stools to do this. Mr Clark thought it great fun to spray any child watching from the cow-shed doorway. He would hold a teat at an angle, squeeze it and the milk from it spurted all over the inquisitive face.

In the dairy all the milk passed through a cooler before going into the big brass churns that had to be heaved up into the milk-float, a two-wheeled cart, and taken into Box. The larger of the churns was placed in the rear of the cart where its tap was at the right level to be used to fill a milk pail, standing on the road. When unattended this tap proved a temptation to mischievous boys, but I can't remember hearing about any major loss of milk.

However winter turned to spring. The celandines and violets peeped out between the dead leaves under the hedges and walls, and birds built new nests. Rooks nested high in the many elms and beech trees which bordered the fields; even now, years later, if I hear the cawing of rooks, I am immediately reminded of The Old Jockey where the sound was so familiar.

Searching for nests in the hedgerow was a regular pastime every spring. Girls didn't steal the eggs but boys did. Perhaps just one from a nest, but another might be taken by a pilferer, and so on till the nest was empty, and the mother bird left bewildered and forlorn. By piercing an egg at both ends with a pin, the yolk could be blown out and the shell added to a treasured collection.

Robins often built their nests in the bank on the side of Short Hill but neither boys nor girls would steal their eggs. It was said that the fingers of the hand that picked up a robin's egg would for ever be fixed in that bent position.

With the arrival of spring the farm became our Mecca once more. New calves and baby chicks were arriving daily. The swing was fixed up in the old apple tree again, and in swinging high on it our feet touched its gnarled branches. Dolly, the eldest of the Clarks, often gave me rides on the carrier of her bike, and much later I learnt to balance on that same bike, after it had been handed down to Vi and then to Walter.

At haymaking time we would all take sandwiches to the hayfield and eat them in a house made of hay. Afterwards we were happy to follow the loaded wagons back to the farm, where the ricks were being made, just to have a ride back to the field when they returned empty to be loaded once more.

Wagons, mowing machines, tosser and rake were all pulled by horses and Captain, one horse, was a soldier for he had served in the Great War. Dumpling, as the name implies, was a chubby comfortable sort of horse, who plodded along quite happily beside his more athletic stable-mate. Witty and Tommy took turns drawing the milk-float. Milking was accomplished by hand and the milkers sat on three-legged stools to do this. Mr Clark thought it great fun to spray any child watching from the cow-shed doorway. He would hold a teat at an angle, squeeze it and the milk from it spurted all over the inquisitive face.

In the dairy all the milk passed through a cooler before going into the big brass churns that had to be heaved up into the milk-float, a two-wheeled cart, and taken into Box. The larger of the churns was placed in the rear of the cart where its tap was at the right level to be used to fill a milk pail, standing on the road. When unattended this tap proved a temptation to mischievous boys, but I can't remember hearing about any major loss of milk.

Chapter 3 Old Jockey Farm

|

As newly-weds, Mr and Mrs Clark came to the farm, and, so I was told, started out with only one cow. While building up his stock, Mr Clark supplemented his income by driving a Post Office mailcart. Using his own horse to draw the cart, he collected letters and parcels from Box and Corsham each evening and took them to the Head Post Office in Chippenham.

After a few hours rest at an inn he would return with the morning mail, carrying it back to the Box and Corsham offices, ready for the postmen to make their deliveries. After driving the mailcart back to The Old Jockey, Mr Clark worked on the farm until it was time to be off to Box again. |

However when my parents and I arrived at The Old Jockey, the mailcart had become redundant and all I can remember of the old vehicle was its broken remains rotting in the orchard. The wheels had disappeared, but the box-like structure that once held the mail still showed traces of post office red paint.

Apparently the farmhouse had been enlarged and the farm buildings improved during the early years of Mr Clark's tenancy and by my childhood days he had increased his herd of cows, which enabled him to have a thriving milk round. Deliveries to Box and district were made twice daily.

Old Jockey Farm became my chief playground and there I spent many happy hours with the Clark children and others who lived nearby. All were welcome. Although I was the youngest in the group I joined in all the games and enjoyed helping with jobs on the farm. Whenever I felt lonely I would run round to Clarks as there was always something going on to interest me. Maybe it was time to fetch the cows from the fields to be milked, or the hens needed to be fed, and I particularly liked colleting the eggs.

By day the hens ran freely in the orchard, and at night roosted on perches in wooden hen-houses. These had to be securely fastened to prevent foxes from killing the birds, and woe betide a hen that wandered off and had no protection during the dark hours. Eggs were laid in the hen-houses and to collect them a long lid at the rear of each house could be raised to expose the row of straw-lined nesting boxes. Sometimes a broody hen had to be forcibly ejected from a nest by being lifted up by the tail. Needless to say she would squawk loud and long to register her disapproval of this treatment.

In the summer we roamed the fields of all the farms around and gathered fruit and flowers in season. Being country children we instinctively understood the country code. We knew it was wrong to trample grass growing for hay or to walk through fields of corn. We knew the hedgerow berries which were edible and those that were poisonous. Such knowledge was no doubt passed on from older child to younger child. Anyway we knew and so none of us came to harm.

Apparently the farmhouse had been enlarged and the farm buildings improved during the early years of Mr Clark's tenancy and by my childhood days he had increased his herd of cows, which enabled him to have a thriving milk round. Deliveries to Box and district were made twice daily.

Old Jockey Farm became my chief playground and there I spent many happy hours with the Clark children and others who lived nearby. All were welcome. Although I was the youngest in the group I joined in all the games and enjoyed helping with jobs on the farm. Whenever I felt lonely I would run round to Clarks as there was always something going on to interest me. Maybe it was time to fetch the cows from the fields to be milked, or the hens needed to be fed, and I particularly liked colleting the eggs.

By day the hens ran freely in the orchard, and at night roosted on perches in wooden hen-houses. These had to be securely fastened to prevent foxes from killing the birds, and woe betide a hen that wandered off and had no protection during the dark hours. Eggs were laid in the hen-houses and to collect them a long lid at the rear of each house could be raised to expose the row of straw-lined nesting boxes. Sometimes a broody hen had to be forcibly ejected from a nest by being lifted up by the tail. Needless to say she would squawk loud and long to register her disapproval of this treatment.

In the summer we roamed the fields of all the farms around and gathered fruit and flowers in season. Being country children we instinctively understood the country code. We knew it was wrong to trample grass growing for hay or to walk through fields of corn. We knew the hedgerow berries which were edible and those that were poisonous. Such knowledge was no doubt passed on from older child to younger child. Anyway we knew and so none of us came to harm.

|

We knew it was unwise to go too near to a cow with a calf, or to disturb a grazing horse. Mr Clark's bull was tied up in a shed. His name was Billy and the nearest we got to him was looking at him over the half-door.

|

Billy the Bull roamed free |

We were guilty of swinging on field gates but knew better than to leave them open. Finding a closed gate obstructing our progress, it was more usual to climb over it, as we did the many dry stone walls in the area.

Mr Reeves of Norbin Farm was the only farmer around who objected to trespassers. His land adjoined Old Jockey Farm and bordering a field called Jefferies there was, and of course is still there, a boggy wood belonging to Mr Reeves. From time to time we crawled under the boundary fence of wire to explore this jungle. Unfamiliar plants thrived in the wet soil. Dodging the marshy spots and searching for these treasures was quite an adventure. If Mr Reeves discovered us he would shout and tell us to clear off, so evading the bogs and Mr Reeves was exciting.

The finest mushrooms grew in the Norbin fields too, and in September we would scramble through another wire fence to search for these delicacies. In sight of the farmhouse here we were very vulnerable, but if not seen we carried home our spoils in our handkerchiefs. A knotted handkerchief was the best way of carrying mushrooms and prevented them from being squashed. Blackberries and hazel-nuts could be found in all the fields and gathering those incurred no risk.

Mr Reeves of Norbin Farm was the only farmer around who objected to trespassers. His land adjoined Old Jockey Farm and bordering a field called Jefferies there was, and of course is still there, a boggy wood belonging to Mr Reeves. From time to time we crawled under the boundary fence of wire to explore this jungle. Unfamiliar plants thrived in the wet soil. Dodging the marshy spots and searching for these treasures was quite an adventure. If Mr Reeves discovered us he would shout and tell us to clear off, so evading the bogs and Mr Reeves was exciting.

The finest mushrooms grew in the Norbin fields too, and in September we would scramble through another wire fence to search for these delicacies. In sight of the farmhouse here we were very vulnerable, but if not seen we carried home our spoils in our handkerchiefs. A knotted handkerchief was the best way of carrying mushrooms and prevented them from being squashed. Blackberries and hazel-nuts could be found in all the fields and gathering those incurred no risk.

|

Both Witty and Tommy knew all the regular stopping places and would stand quite still until the driver returned. Housewives came to their door with jugs and these would be filled by the milkman dipping a pint or half-pint measure into the pail for the required amount. Then perhaps another quick dip with a drop more just for good measure.

The brass churns were incised with letters showing that they belonged to A. Clark. Old Jockey Farm and were always well polished. I believe the brass was an extra layer of metal over a normal steel churn. The brass only covered the upper part. The shining churns in the red and yellow milk-float were familiar in the village, and with the clip-clop of the horses' feet proved a pleasant sight and sound whenever they passed by. As Dolly and Vi left school they helped with the milk deliveries, and sometimes in the summer holidays would let me accompany them. Left: Tommy and Witty, milk cart horses |

They took orders for poultry, eggs and Mrs Clark's very tasty faggots, so customers were able to have these farmhouse delights delivered to their doors.Harvest time was a special and important season of the farming year, and I was always willing to carry jugs of Mrs Clark's home-made lemonade to the men working in the fields, and happy to linger there and watch the binder at work. This machine cut off the wheat, oats or barley a few inches from the ground and miraculously tied the stalks into sheaves with string known as binder-twine.

The sheaves were gathered up and piled into tent-shaped stooks with the grain heads, the ears, uppermost, and left to dry in the sun. After two or three days the sheaves were loaded onto wagons, taken to the farmyard and made into ricks. Later these corn-ricks were dismantled and the grain threshed out, leaving the stalks to be used as straw. The threshing machine was hired and was taken from farm to farm in the autumn. It was pulled by a traction-engine, and when it was due at the Clarks, the yard gate was taken off its hinges to allow a few extra inches for the entrance of this monster.

Extra labour was engaged at threshing time as the process required many hands. The ricks built at harvest were taken apart and each sheaf fed into the machine. This was driven by endless belts attached to the traction-engine and supervised by the engine driver. While working it made a lot of noise and smoke and much dust flew out of the thresher. Children had to keep well away.The separated grain poured out into sacks hooked onto a chute at the side of the thresher, and the stalks were ejected from another part of the machine, with twine again firmly tied around each sheaf. At the same time, new ricks were being made of this straw, all ready for use as food or bedding for the cattle in the winter. The ricks needed to be thatched to protect them from rain and snow. The sacks of grain would be sold to a miller. Probably it went to the mill at Box.

The sheaves were gathered up and piled into tent-shaped stooks with the grain heads, the ears, uppermost, and left to dry in the sun. After two or three days the sheaves were loaded onto wagons, taken to the farmyard and made into ricks. Later these corn-ricks were dismantled and the grain threshed out, leaving the stalks to be used as straw. The threshing machine was hired and was taken from farm to farm in the autumn. It was pulled by a traction-engine, and when it was due at the Clarks, the yard gate was taken off its hinges to allow a few extra inches for the entrance of this monster.

Extra labour was engaged at threshing time as the process required many hands. The ricks built at harvest were taken apart and each sheaf fed into the machine. This was driven by endless belts attached to the traction-engine and supervised by the engine driver. While working it made a lot of noise and smoke and much dust flew out of the thresher. Children had to keep well away.The separated grain poured out into sacks hooked onto a chute at the side of the thresher, and the stalks were ejected from another part of the machine, with twine again firmly tied around each sheaf. At the same time, new ricks were being made of this straw, all ready for use as food or bedding for the cattle in the winter. The ricks needed to be thatched to protect them from rain and snow. The sacks of grain would be sold to a miller. Probably it went to the mill at Box.

|