|

Kingsdown Fair

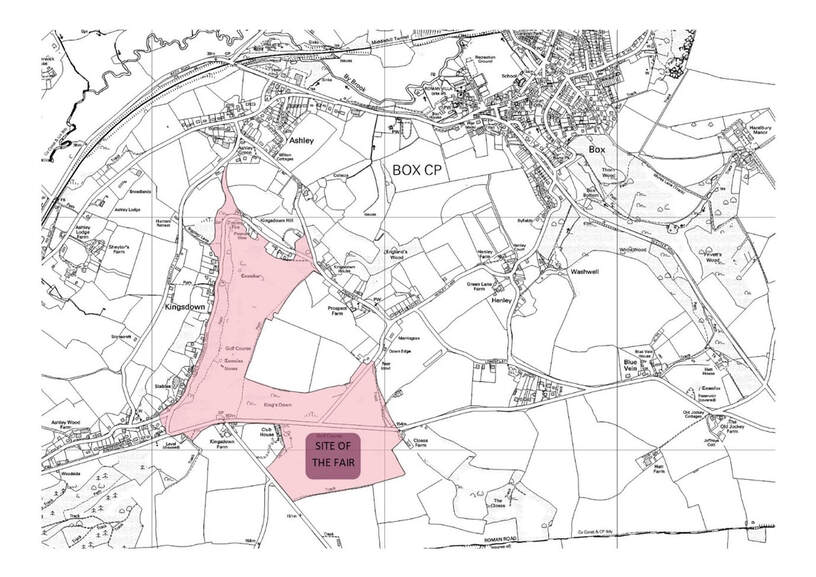

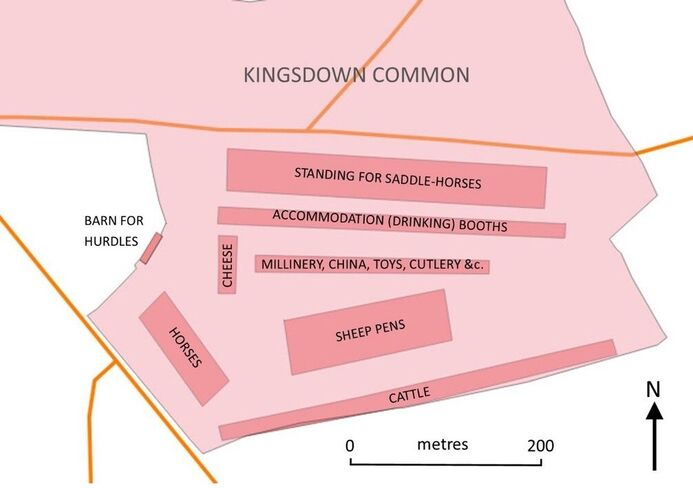

Rob Arkell May 2021 The use of Kingsdown as an annual fair is well-known but its history has never been fully recorded before. Rob Arkell's knowledge of the fairs is second-to-none and he is the author of the brochure about the fair at nearby Bradford Leigh. We are indebted to him for this article. Kingsdown Fair was best known as a sheep fair but cattle, horses and cheese were also sold. The fair was held on the southern portion of the 124 acre Kingsdown Common. Right: Lansdown Horse Fair in 1903 © Bath and North East Somerset Archives & Local Studies |

Medieval Charter Fairs

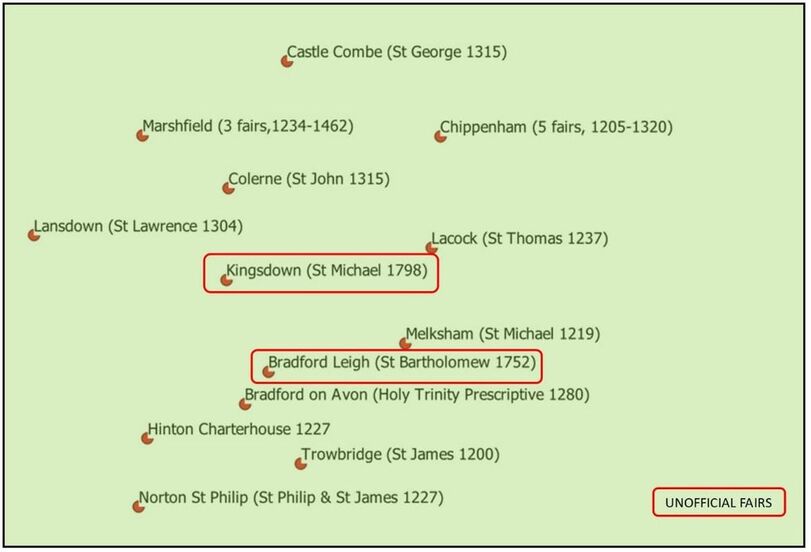

Fairs were established to provide venues for trade and they attracted entertainments to be enjoyed when the buying and selling had been completed. Some fairs were in existence in the 12th century but after that date they could only be held with permission granted in a royal charter. The charter specified the person who was to benefit from the fair, the date of the fair' start (often a saint’s day, usually the patronal saint of the local church), the number of days the fair could be held before and after the saint’s day, and the place at which it was to be held. These charters have been extensively researched and are available in an on-line database.[1] The relative positions of local charter fairs together with Kingsdown and Bradford Leigh Fairs are shown below.

Fairs were established to provide venues for trade and they attracted entertainments to be enjoyed when the buying and selling had been completed. Some fairs were in existence in the 12th century but after that date they could only be held with permission granted in a royal charter. The charter specified the person who was to benefit from the fair, the date of the fair' start (often a saint’s day, usually the patronal saint of the local church), the number of days the fair could be held before and after the saint’s day, and the place at which it was to be held. These charters have been extensively researched and are available in an on-line database.[1] The relative positions of local charter fairs together with Kingsdown and Bradford Leigh Fairs are shown below.

Kingsdown and Bradford Leigh Fair do not appear on the database indicating that that they were unofficial fairs without medieval origins. Unofficial fairs began to appear in the 17th century and like their medieval counterparts were a means of making money though the charging of tolls on sales and charging for pitches on the fairground.

There are a few records of Kingsdown Fair held at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre and some written reminiscences [2] but the British Newspaper Archive provides the bulk of the information available with reports from 1798 to 1945. Most references to the fair are in syndicated copies of the prices fetched by sheep, cattle and cheese but there are a few more detailed articles related to a newsworthy event such as an outbreak of disease, an accident or a crime committed. Interest in the prices obtained at Kingsdown Fair was sufficient to warrant publication across the whole of the United Kingdom including the Dublin Evening Mail, the South Wales Daily News, the Inverness Courier and the Edinburgh Evening News.

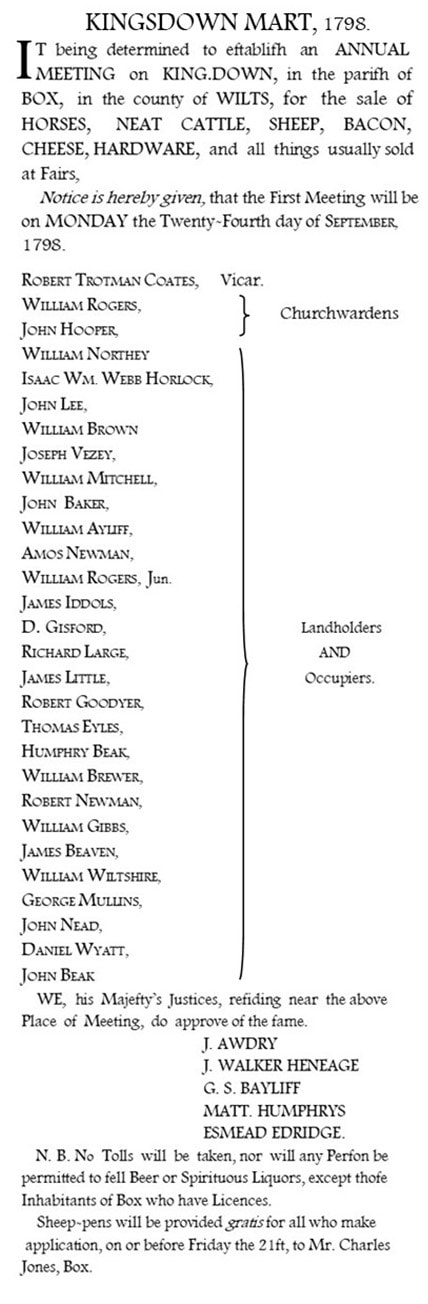

A reference to a court case in 1861 concerning Kingsdown Fair found in the Bath Chronicle confirms the unofficial nature of the fair as it is described as not a fair in the legal sense of the word or in any way an incorporeal hereditament but simply the occupation of Kingsdown for several consecutive days for a horse, sheep and other cattle fair, the animals being placed in pens on the down and payments being thereupon made for pens etc.[3] Within the last few years early editions of the Gloucester Journal have been added to the British Newspaper Archive database so that a search for Kingsdown now provides a newspaper announcement dating the start of the fair to 1798.[4]

A reference to a court case in 1861 concerning Kingsdown Fair found in the Bath Chronicle confirms the unofficial nature of the fair as it is described as not a fair in the legal sense of the word or in any way an incorporeal hereditament but simply the occupation of Kingsdown for several consecutive days for a horse, sheep and other cattle fair, the animals being placed in pens on the down and payments being thereupon made for pens etc.[3] Within the last few years early editions of the Gloucester Journal have been added to the British Newspaper Archive database so that a search for Kingsdown now provides a newspaper announcement dating the start of the fair to 1798.[4]

|

William Northey (known as William of Hazelbury) heads the list of landowners and occupiers and as Lord of the Manor of Box he was legally entitled to the profits of the fair. After his death in 1826 the manor passed jointly to his nephews Edward Richard Northey (b 1795) and William Brook Northey (b 1805), who were joint owners at the time of the Tithe Map. Edward lived in Surrey after leaving the army and appears to have nominated his younger brother, who lived locally, to be Lord of the Manor, based on the court case in 1861. Edward seems to have dealt with the financial affairs of the manor however and his name alone appears on the conveyance of land in Box and Ditteridge sold to the Great Western Railway Company in 1839 for the considerable sum of £2439. 5s.[5]

Kingsdown Fair followed Lansdown Fair which was held either side of August 10th and Bradford Leigh Fair which was held at the end of August. Kingsdown was well placed to attract the inhabitants of Bath, Chippenham, Melksham and Bradford on Avon. The choice of the Monday before Michaelmas may just have been pragmatic or it may have reflected the rivalry between Box and Colerne, with a desire to take trade away from Colerne Fair which was held at the end of August, and which sometimes ended with fighting between the menfolk of Box and Colerne.[6] The 1798 notice states that no tolls would be taken, and it was called a mart or meeting, following a pattern established by those wishing to start a fair, but who were still wary of calling it a fair as this technically required a royal or parliamentary charter. Once the event became established then tolls were introduced, and this seems to have happened by 1808 when booth holders were required to attend a week before the fair at the Swan Inn to mark out their pitch and also to pay.[7] It appears that sheep were charged by the pen. Cheese paid a toll per hundredweight and locally the charge at Lansdown Fair in 1811 was 2d per cwt, whilst at Bradford Leigh Fair in 1869 it was 1d per cwt. Kingsdown Fair was still being referred to as a mart in local annual announcements up to 1818 but was called a fair when reported in other newspapers. Lansdown and Bradford Leigh fairs had a reputation for drunkenness and violence and to prevent this happening the sale of beer and spirits was originally to have been restricted to inhabitants of Box with licences. This restriction must however have been reversed before the first fair as eighteen genteel accommodation booths (uncertain meaning but possibly alcohol) were reported when the first mart was recorded in the Birmingham Gazette of 1st Oct 1798, in what was clearly an advertorial. Right: Facsimile of the announcement of the first Kingsdown Fair (courtesy Rob Arkell) |

Report of the First Kingsdown Fair, 1798

The Birmingham Gazette of 1st Oct 1798 reported events at the first Kingsdown Fair:

KINGSDOWN MART

The first fair on Kingsdown was as well attended on Monday last as its most sanguine promoters could wish, and its permanent establishment is insured; it was held on that beautiful lawn the south side of the London road. The resolution of confining the sale of beer, &c. to the inhabitants of Box being rescinded, a range of eighteen genteel accommodation booths made their appearance, running parallel to the road, at a distance of 100 yards, leaving a convenient standing for the saddle-horses, without incommoding the company in front. The sheep-pens (containing near 4000 sheep, of which less than 1000 remained unsold) occupied a spot in the middle, the neat cattle skirted the southern boundary, and a handsome show of horses the west; leaving the east open to the numerous droves of sheep, cattle, and pigs, that were continually diversifying the scene. A row of standings for millinery, china, toys, cutlery, &c. placed opposite the booths, formed a parade of 100 feet wide, at the west end of which was pitched some prime cheese. The E. O. (Even Odd – an early form of roulette) tables, and all other inducements to disorder being supressed, a genteel assemblage of near 10,000 people saw with regret the setting sun give notice to depart. Cattle in general sold well, cheese from 33s. to 44s. per cwt. – The second day’s fair was dismissed with a well contested country race for a subscription purse.

The Birmingham Gazette of 1st Oct 1798 reported events at the first Kingsdown Fair:

KINGSDOWN MART

The first fair on Kingsdown was as well attended on Monday last as its most sanguine promoters could wish, and its permanent establishment is insured; it was held on that beautiful lawn the south side of the London road. The resolution of confining the sale of beer, &c. to the inhabitants of Box being rescinded, a range of eighteen genteel accommodation booths made their appearance, running parallel to the road, at a distance of 100 yards, leaving a convenient standing for the saddle-horses, without incommoding the company in front. The sheep-pens (containing near 4000 sheep, of which less than 1000 remained unsold) occupied a spot in the middle, the neat cattle skirted the southern boundary, and a handsome show of horses the west; leaving the east open to the numerous droves of sheep, cattle, and pigs, that were continually diversifying the scene. A row of standings for millinery, china, toys, cutlery, &c. placed opposite the booths, formed a parade of 100 feet wide, at the west end of which was pitched some prime cheese. The E. O. (Even Odd – an early form of roulette) tables, and all other inducements to disorder being supressed, a genteel assemblage of near 10,000 people saw with regret the setting sun give notice to depart. Cattle in general sold well, cheese from 33s. to 44s. per cwt. – The second day’s fair was dismissed with a well contested country race for a subscription purse.

Length of the Fair

Descriptions of the fair in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries refer to a sale of stock in the morning, and a funfair in the afternoon, but a second day is referred to in 1798 and the article in 1861 refers to consecutive days, so it appears that the funfair continued into the next day for many years.[8] Some of the stalls also did business on the Sunday beforehand so that at its peak it was a three-day fair.[9] This can be contrasted with Bradford Leigh Fair which lasted for 8 days and Lansdown Fair which originally lasted for 8 days but was extended to 10 days by Queen Anne in 1708.

Date Change

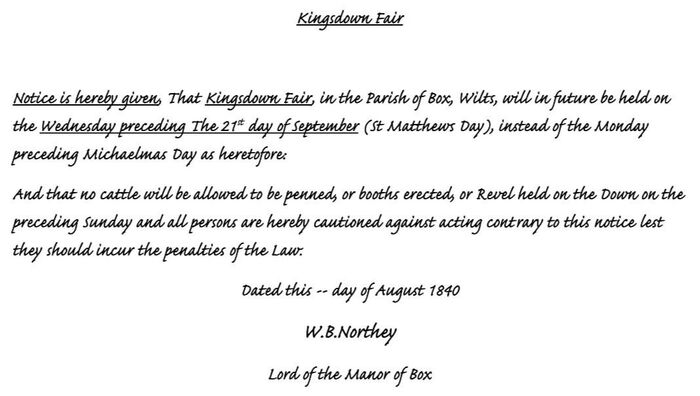

In 1840 William Brook Northey changed the date of Kingsdown Fair from the Monday before Michaelmas (29 September) to the Wednesday preceding 21 September (St Mathew’s Day). His handwritten notice is transcribed below:[10]

Descriptions of the fair in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries refer to a sale of stock in the morning, and a funfair in the afternoon, but a second day is referred to in 1798 and the article in 1861 refers to consecutive days, so it appears that the funfair continued into the next day for many years.[8] Some of the stalls also did business on the Sunday beforehand so that at its peak it was a three-day fair.[9] This can be contrasted with Bradford Leigh Fair which lasted for 8 days and Lansdown Fair which originally lasted for 8 days but was extended to 10 days by Queen Anne in 1708.

Date Change

In 1840 William Brook Northey changed the date of Kingsdown Fair from the Monday before Michaelmas (29 September) to the Wednesday preceding 21 September (St Mathew’s Day). His handwritten notice is transcribed below:[10]

The date change was in response to an approach from The Bath Lord’s Day Observance Society. Their Committee report in 1843 recorded their activities against fairs:[11] Your Committee have not failed again to give their attention to the evils attendant upon fairs in the neighbourhood, and to prevent, as far as possible, the revels usually taking place on the previous Lord’s day. At the instance of your Committee, the magistrates issued a caution previous to the Lansdown Fair, held in the month of August, warning all persons against selling any excisable liquor or beer, or doing any other unlawful act on the preceding Sunday. The lord of the Manor Box, at the suggestion of your Committee, was again pleased to issue a notice to remind the public of the alteration, which he had previously sanctioned, of Kingsdown Fair to Wednesday, in order to prevent any interruption of the duties of the Lord’s day, which used to take place when the fair was held on a Monday.

Your Committee are anxious to prevent the revel on the Lord’s day which precedes Bradford Leigh Fair, and have been in correspondence on the subject with the proper authorities, but they are not yet able to report any favourable result.

The Bath Lord’s Day Observance Society did indeed approach Sir John Cam Hobhouse, Lord of the manor of Bradford-on-Avon, and asked him to change the day of the fair. He took legal advice, which was that as the fair was not held by a legal grant, and the date had been enshrined in the 1820 Enclosure Act, then a change to the date would mean that the fair could not be held at all. The date of Bradford Leigh Fair was therefore not changed [12].

Your Committee are anxious to prevent the revel on the Lord’s day which precedes Bradford Leigh Fair, and have been in correspondence on the subject with the proper authorities, but they are not yet able to report any favourable result.

The Bath Lord’s Day Observance Society did indeed approach Sir John Cam Hobhouse, Lord of the manor of Bradford-on-Avon, and asked him to change the day of the fair. He took legal advice, which was that as the fair was not held by a legal grant, and the date had been enshrined in the 1820 Enclosure Act, then a change to the date would mean that the fair could not be held at all. The date of Bradford Leigh Fair was therefore not changed [12].

The newspaper report for 1840, the year of the date change, is given below:[13]

KINGSDOWN FAIR

This fair was held yesterday. In the cattle market there was a great falling off in the amount of business done, compared with that of former years, and in proportion to the extent of stock for sale. The show of beasts was not very large, and although buyers were numerous, yet they were unwilling to give the prices asked. Good stock beasts realised from 10s. to 10s. 6d. per score, but very little business was contracted in those of an inferior quality. Of stock sheep the supply was unusually large, and sellers were obliged to submit to a reduction of from 2s. to 3s. per head on the prices of last year, owning to the scarcity of grass. Two-tooth wethers exchanged hands at sums varying from 25s. to 40s. There was a great scarcity of lambs, and those in the market were not of a superior description; they sold well at 7d per lb. The Horse Fair presented a most miserable appearance as to quality; we have not heard of a single hunter or carriage horse being on the ground. There was, however, no lack of numbers. This was the first fair held since the change from the Monday before Michaelmas to the Wednesday before St. Matthews day, and we are informed that the farmers are well pleased with the alteration, not only on account of its allowing more time before Michaelmas for the settlement of their accounts, but also on account of their being relieved from the necessity of driving there on the preceding Sunday. A desire also exists among some of them to have the Bradford Leigh fair changed from Monday to Wednesday for the latter reason .

KINGSDOWN FAIR

This fair was held yesterday. In the cattle market there was a great falling off in the amount of business done, compared with that of former years, and in proportion to the extent of stock for sale. The show of beasts was not very large, and although buyers were numerous, yet they were unwilling to give the prices asked. Good stock beasts realised from 10s. to 10s. 6d. per score, but very little business was contracted in those of an inferior quality. Of stock sheep the supply was unusually large, and sellers were obliged to submit to a reduction of from 2s. to 3s. per head on the prices of last year, owning to the scarcity of grass. Two-tooth wethers exchanged hands at sums varying from 25s. to 40s. There was a great scarcity of lambs, and those in the market were not of a superior description; they sold well at 7d per lb. The Horse Fair presented a most miserable appearance as to quality; we have not heard of a single hunter or carriage horse being on the ground. There was, however, no lack of numbers. This was the first fair held since the change from the Monday before Michaelmas to the Wednesday before St. Matthews day, and we are informed that the farmers are well pleased with the alteration, not only on account of its allowing more time before Michaelmas for the settlement of their accounts, but also on account of their being relieved from the necessity of driving there on the preceding Sunday. A desire also exists among some of them to have the Bradford Leigh fair changed from Monday to Wednesday for the latter reason .

The Value of the Fair

The value of the fair at two different dates is known because of the court case in 1861.[14] The fair was rented annually in 1841 by William Brook Northey to William Mizen, separately from a farm near the common which he rented from William and Edward Northey. The rent was £10 payable at Michaelmas and this arrangement continued with another Mizen, Henry until 1859 when Edward Northey cancelled the agreement on behalf of his brother William.

I hereby give you notice that it is my intention to terminate, from and after the 29th day of September next , the grant of the privilege of holding a fair on Kingsdown, in the parish of Box, Wilts, and of receiving tolls and payments on account thereof, which you now hold of me, as yearly tenant, and that from and after that period all rights to privileges which you now enjoy from me in respect of Kingsdown Fair will wholly cease and determine – dated the 8th day of March 1859 – EDWARD R. NORTHEY, for W.B. NORTHEY. – To Mr. Henry Mizen, Coombhay

Henry Mizen held the fair as usual in 1859 and in October 1859 he replied that he would not give the fair up as the notice was not properly signed. The Northeys then gave Mizen notice to quit the farm at the next breakpoint in the tenancy in 1861. Henry Mizen was warned not to hold the fair by the Northey’s bailiff on September 13th 1860, but despite this he still held the fair on September 19th. Mizen was then taken to court for wilfully holding over after the determination of the tenancy and lost the case, which made him liable for double the rent. The Judge ruled that the true value of the fair was now at least £26 per year but William Northey agreed to limit his claim to £50.

The value of the fair at two different dates is known because of the court case in 1861.[14] The fair was rented annually in 1841 by William Brook Northey to William Mizen, separately from a farm near the common which he rented from William and Edward Northey. The rent was £10 payable at Michaelmas and this arrangement continued with another Mizen, Henry until 1859 when Edward Northey cancelled the agreement on behalf of his brother William.

I hereby give you notice that it is my intention to terminate, from and after the 29th day of September next , the grant of the privilege of holding a fair on Kingsdown, in the parish of Box, Wilts, and of receiving tolls and payments on account thereof, which you now hold of me, as yearly tenant, and that from and after that period all rights to privileges which you now enjoy from me in respect of Kingsdown Fair will wholly cease and determine – dated the 8th day of March 1859 – EDWARD R. NORTHEY, for W.B. NORTHEY. – To Mr. Henry Mizen, Coombhay

Henry Mizen held the fair as usual in 1859 and in October 1859 he replied that he would not give the fair up as the notice was not properly signed. The Northeys then gave Mizen notice to quit the farm at the next breakpoint in the tenancy in 1861. Henry Mizen was warned not to hold the fair by the Northey’s bailiff on September 13th 1860, but despite this he still held the fair on September 19th. Mizen was then taken to court for wilfully holding over after the determination of the tenancy and lost the case, which made him liable for double the rent. The Judge ruled that the true value of the fair was now at least £26 per year but William Northey agreed to limit his claim to £50.

Cheese

Cheese was widely sold at local fairs with cheese prices being given for Bradford Leigh Fair from 1788 to 1844. Cheese was sold at the first Kingsdown fair in 1798 and there are newspaper reports giving cheese prices at the fair in 1798, 1822, 1829, 1831 and 1835. The cheese market which opened in Chippenham in 1834 may have caused the decline of cheese at Kingsdown Fair after this date. The quality of cheese varied from skim at 20-32s/ cwt, Best Coward (a cheese made from half full fat and half skim milk) at 40-56s/ cwt and prime Old Somerset at 69s/ cwt. In 1835 the report of the fair laconically stated no Old Somerset on the Down.[15] Cheese was brought to the fair in sturdy wagons with extra-wide wheels.

The Fair in the 1880s

Samuel Kendall, whose father farmed land in Monkton Farleigh, South Wraxall, Box and Bathford described the fair in his memoirs.[16] In the 1880s The Great Sale ran from 10.00 am to 2.00 pm. Animals were sold by private barter with only pure-bred and highly priced rams being sold by auction. After the sale some animals were driven away immediately, some returned to local farms before an early start the next morning and some were despatched on the GWR from Box.

Local employees would be given a half-day holiday to attend the fair. Attractions were coconut shies, swings, roundabouts with popular music, rifle shooting at bottles and pipes, freak shows and other creations, especially concocted to amuse our country lads and lassies. A boxing booth provided not only male but female opponents or a black man willing to take on all and sundry. George Betteridge, foreman of the Bath and Portland Stone Company and a one-time landlord of the Swan Inn was a well-known boxer in his youth and fought in the booths at Kingsdown Fair.[17] He died in 1949 aged 86 so he may well have been seen by Samuel Kendall in the 1880s.

Horse Racing

The well contested country race for a subscription purse which took place on the second day of the fair in 1798 is the only reference to horse racing at Kingsdown. The value of the purse is not given but in theory was at least £50 as the government had attempted to restrict horse racing to the upper classes by setting a minimum purse of this value. A case was brought against a Bath printer in 1815 for printing handbills for races at Bradford Leigh Fair with prizes less than £50.[18]

The Perils of the Fair

Kingsdown does not seem to have been the site of the type of lurid activities seen at Bradford Leigh (riot) and at Lansdown (riot, rape and a shooting). The announcement of the first meeting includes the approval of five local Justices of the Peace, presumably to indicate that the fair would be respectable. Police were still very visible at the fair in the early 1900s:There were many policemen around just to see things didn't get too much out of hand.[19] Nevertheless some crimes were recorded. A man was remanded in Chippenham in 1838 for picking the pocket of a Mr Day from Atford (Atworth) of £40 at the fair.[20] In 1876 two men were apprehended in a Trowbridge boarding house having been accused of Highway Robbery following the fair.[21]

Travelling to the fair was not without its dangers and in 1831 a Bath man died, and two companions were seriously injured, when their one-horse phaeton ran away after some harness broke while going down Kingsdown Hill after the second day of the fair.[22]

Cheese was widely sold at local fairs with cheese prices being given for Bradford Leigh Fair from 1788 to 1844. Cheese was sold at the first Kingsdown fair in 1798 and there are newspaper reports giving cheese prices at the fair in 1798, 1822, 1829, 1831 and 1835. The cheese market which opened in Chippenham in 1834 may have caused the decline of cheese at Kingsdown Fair after this date. The quality of cheese varied from skim at 20-32s/ cwt, Best Coward (a cheese made from half full fat and half skim milk) at 40-56s/ cwt and prime Old Somerset at 69s/ cwt. In 1835 the report of the fair laconically stated no Old Somerset on the Down.[15] Cheese was brought to the fair in sturdy wagons with extra-wide wheels.

The Fair in the 1880s

Samuel Kendall, whose father farmed land in Monkton Farleigh, South Wraxall, Box and Bathford described the fair in his memoirs.[16] In the 1880s The Great Sale ran from 10.00 am to 2.00 pm. Animals were sold by private barter with only pure-bred and highly priced rams being sold by auction. After the sale some animals were driven away immediately, some returned to local farms before an early start the next morning and some were despatched on the GWR from Box.

Local employees would be given a half-day holiday to attend the fair. Attractions were coconut shies, swings, roundabouts with popular music, rifle shooting at bottles and pipes, freak shows and other creations, especially concocted to amuse our country lads and lassies. A boxing booth provided not only male but female opponents or a black man willing to take on all and sundry. George Betteridge, foreman of the Bath and Portland Stone Company and a one-time landlord of the Swan Inn was a well-known boxer in his youth and fought in the booths at Kingsdown Fair.[17] He died in 1949 aged 86 so he may well have been seen by Samuel Kendall in the 1880s.

Horse Racing

The well contested country race for a subscription purse which took place on the second day of the fair in 1798 is the only reference to horse racing at Kingsdown. The value of the purse is not given but in theory was at least £50 as the government had attempted to restrict horse racing to the upper classes by setting a minimum purse of this value. A case was brought against a Bath printer in 1815 for printing handbills for races at Bradford Leigh Fair with prizes less than £50.[18]

The Perils of the Fair

Kingsdown does not seem to have been the site of the type of lurid activities seen at Bradford Leigh (riot) and at Lansdown (riot, rape and a shooting). The announcement of the first meeting includes the approval of five local Justices of the Peace, presumably to indicate that the fair would be respectable. Police were still very visible at the fair in the early 1900s:There were many policemen around just to see things didn't get too much out of hand.[19] Nevertheless some crimes were recorded. A man was remanded in Chippenham in 1838 for picking the pocket of a Mr Day from Atford (Atworth) of £40 at the fair.[20] In 1876 two men were apprehended in a Trowbridge boarding house having been accused of Highway Robbery following the fair.[21]

Travelling to the fair was not without its dangers and in 1831 a Bath man died, and two companions were seriously injured, when their one-horse phaeton ran away after some harness broke while going down Kingsdown Hill after the second day of the fair.[22]

The Sheep Fair

Kingsdown was an integral part of a nationwide sheep trading network and as early as 1817 a dealer from Norfolk purchased 2000 sheep.[23] The reach of the fair was expanded further once the Great Western Railway opened in 1841. The fair was described as the chief annual sheep mart in the West of England in 1876,[24] and in 1878 as This important fair, which, coming so close after Wilton, is looked upon as having a great influence in settling the autumnal price of sheep.[25] By 1878 special trains were being laid on from Box which were much appreciated by dealers despatching large flocks to a distance.[26] If flocks needed to go beyond London then it appears to have been more convenient to drive the sheep to the nearest standard gauge railway station, rather than having to make the transfer from the GWR’s broad gauge network to the standard gauge network in London. The GWR changed to standard gauge in 1892. Evidence for this is found in 1887 when a dealer from Wakefield purchased 307 sheep which were driven to Wilton from where they could be sent by train to King’s Cross, instead of being shipped from Box.[27]

Samuel Kendall described how on the afternoon and evening of the day before the fair great flocks of tired dusty sheep from Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Somerset blocked the local roads before finding somewhere to stay overnight prior to the fair. Lambs were distressed and upset after their long and dusty journey and flocks would sometimes become mixed up and then had to be painstakingly sorted out.[28] Some sheep arrived days or even weeks before the fair.[29] Drovers were engaged by dealers to drive sheep both to the fair and from the fair to their destination. The drovers engaged by the Wakefield dealer in 1887 stopped at Steeple Ashton overnight. Eleven sheep from a neighbouring field had disappeared by the next morning and the two drovers were found to have added them to their flock for shipment to London where they separated them out and sold ten for £11 13s 1d. The remaining sheep was sold at Yarnborough Fair, near Steeple Langford, on the 4th October, which the drovers would have passed on their way to Wilton. One of the drovers claimed that he was too drunk to have noticed the extra sheep in the flock but both were convicted and given 6 months and 4 months hard labour respectively as it was a first offence.

An idea of the distance travelled by the sheep on foot is given by an enquiry on October 3rd 1865 [30] into the spread of cattle plague (Rinderpest) at Mildenhall near Marlborough. Forty sheep had started their journey at Bristol on September 1st. They were joined by another thirty bought at Bradford Leigh Fair which would have been held on 28th August that year. One collapsed in Box on the way to Kingsdown Fair on the day before the fair, 20th September, and later died. After being sold at Kingsdown the remaining sixty-nine sheep were driven to Chippenham by the night of the 21st (8½ miles) where they rested overnight before continuing via Cherhill to Mildenhall (21.5 miles) which they reached at 10pm on the 22nd September. Forty-nine of the sheep had died of the cattle plague by the date of the enquiry, and the survivors, and another forty which they had been in contact with, were killed and buried five feet deep in a lime pit on the same day.

Kingsdown was an integral part of a nationwide sheep trading network and as early as 1817 a dealer from Norfolk purchased 2000 sheep.[23] The reach of the fair was expanded further once the Great Western Railway opened in 1841. The fair was described as the chief annual sheep mart in the West of England in 1876,[24] and in 1878 as This important fair, which, coming so close after Wilton, is looked upon as having a great influence in settling the autumnal price of sheep.[25] By 1878 special trains were being laid on from Box which were much appreciated by dealers despatching large flocks to a distance.[26] If flocks needed to go beyond London then it appears to have been more convenient to drive the sheep to the nearest standard gauge railway station, rather than having to make the transfer from the GWR’s broad gauge network to the standard gauge network in London. The GWR changed to standard gauge in 1892. Evidence for this is found in 1887 when a dealer from Wakefield purchased 307 sheep which were driven to Wilton from where they could be sent by train to King’s Cross, instead of being shipped from Box.[27]

Samuel Kendall described how on the afternoon and evening of the day before the fair great flocks of tired dusty sheep from Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Somerset blocked the local roads before finding somewhere to stay overnight prior to the fair. Lambs were distressed and upset after their long and dusty journey and flocks would sometimes become mixed up and then had to be painstakingly sorted out.[28] Some sheep arrived days or even weeks before the fair.[29] Drovers were engaged by dealers to drive sheep both to the fair and from the fair to their destination. The drovers engaged by the Wakefield dealer in 1887 stopped at Steeple Ashton overnight. Eleven sheep from a neighbouring field had disappeared by the next morning and the two drovers were found to have added them to their flock for shipment to London where they separated them out and sold ten for £11 13s 1d. The remaining sheep was sold at Yarnborough Fair, near Steeple Langford, on the 4th October, which the drovers would have passed on their way to Wilton. One of the drovers claimed that he was too drunk to have noticed the extra sheep in the flock but both were convicted and given 6 months and 4 months hard labour respectively as it was a first offence.

An idea of the distance travelled by the sheep on foot is given by an enquiry on October 3rd 1865 [30] into the spread of cattle plague (Rinderpest) at Mildenhall near Marlborough. Forty sheep had started their journey at Bristol on September 1st. They were joined by another thirty bought at Bradford Leigh Fair which would have been held on 28th August that year. One collapsed in Box on the way to Kingsdown Fair on the day before the fair, 20th September, and later died. After being sold at Kingsdown the remaining sixty-nine sheep were driven to Chippenham by the night of the 21st (8½ miles) where they rested overnight before continuing via Cherhill to Mildenhall (21.5 miles) which they reached at 10pm on the 22nd September. Forty-nine of the sheep had died of the cattle plague by the date of the enquiry, and the survivors, and another forty which they had been in contact with, were killed and buried five feet deep in a lime pit on the same day.

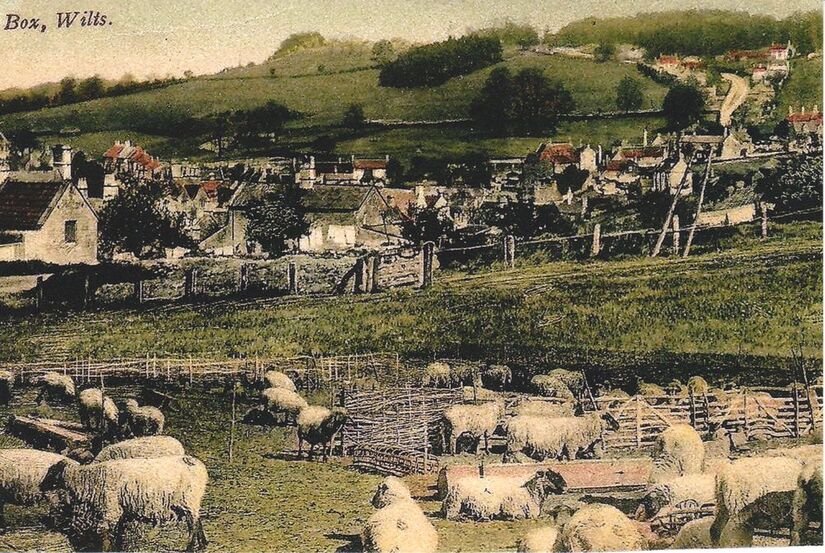

Sheep Pens

Sheep were sold by the pen and the pens, made from split ash hurdles, can be seen in the foreground of the postcard above. Pens to sell thousands of sheep must have required many hurdles and these were stored in the barn on the common now used by the Golf Club. Once sheep had been sold they would have been driven away by their new owner freeing up the pens for another flock. In 1835 the Fair was the largest for sheep ever remembered; the supply being so great that pens could not be procured for all that were brought.[31] In 1868 when 60,000 sheep were reckoned to have been sold there was, unsurprisingly, a report of the number of hurdles ‘pitched’ being taxed to the utmost of their limits.[32]

Sheep were sold by the pen and the pens, made from split ash hurdles, can be seen in the foreground of the postcard above. Pens to sell thousands of sheep must have required many hurdles and these were stored in the barn on the common now used by the Golf Club. Once sheep had been sold they would have been driven away by their new owner freeing up the pens for another flock. In 1835 the Fair was the largest for sheep ever remembered; the supply being so great that pens could not be procured for all that were brought.[31] In 1868 when 60,000 sheep were reckoned to have been sold there was, unsurprisingly, a report of the number of hurdles ‘pitched’ being taxed to the utmost of their limits.[32]

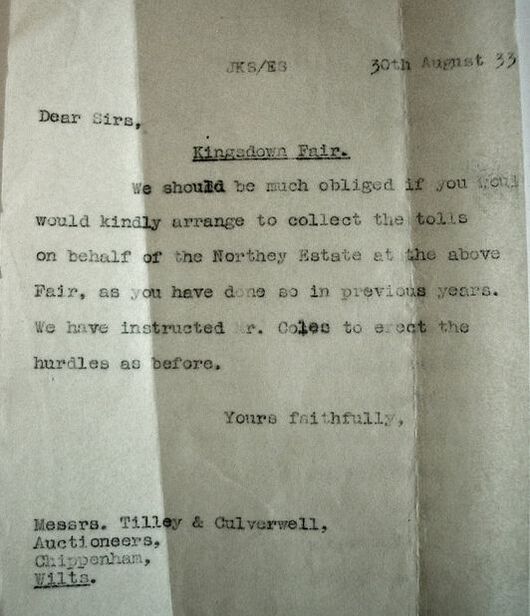

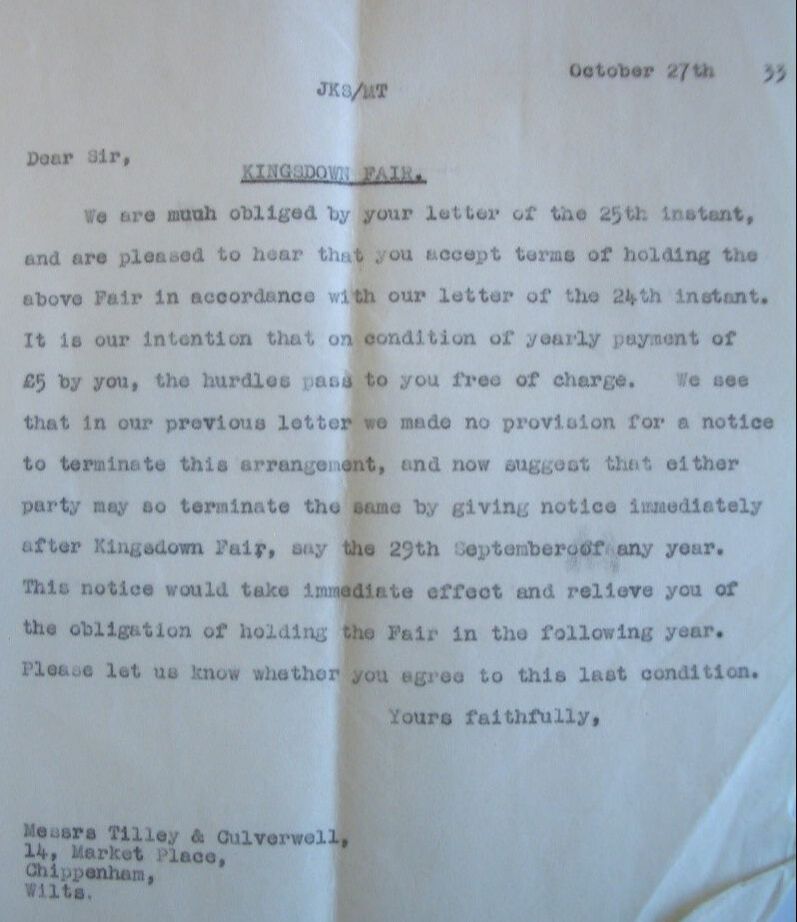

Some correspondence between the Northey estate and Tilley & Culverwell, auctioneers, who ran the fair for the estate, survives from 1933.[33] A letter dated 30th August asked Tilley & Culverwell to continue collecting the tolls and confirms that the estate will erect the hurdles (below left). A letter dated 27th October 1933 discusses Tilley & Culverwell taking ownership of the hurdles and the possibility of ceasing to hold the fair, reflecting the fact that the fair was in decline by this date (below right).

The Horse Fair

Horses were the primary means of local transport until just after the first world war and country fairs always included some horses. The first fair had a handsome show of horses. In 1840 the Horse Fair presented a most miserable appearance as to quality; we have not heard of a single hunter or carriage horse being on the ground.[34] Victor Painter, writing about the fair around the time of World War I, described the horses as all dressed up with straw and ribbons in their hair and tails.[35]

The account of the fair in 1924 comments that there are no horse to be disposed of, for the coming of the car has almost killed the horse trade.[36]

Horses were the primary means of local transport until just after the first world war and country fairs always included some horses. The first fair had a handsome show of horses. In 1840 the Horse Fair presented a most miserable appearance as to quality; we have not heard of a single hunter or carriage horse being on the ground.[34] Victor Painter, writing about the fair around the time of World War I, described the horses as all dressed up with straw and ribbons in their hair and tails.[35]

The account of the fair in 1924 comments that there are no horse to be disposed of, for the coming of the car has almost killed the horse trade.[36]

Fairs attracted criminals and buying a horse at a fair could be a costly mistake. If you were not careful you could sell a horse in the morning and end up buying it back in the afternoon with an altered appearance and its faults camouflaged. Confidence tricksters fooled the unwary. One such incident occurred at Melksham fair in 1842:[37]

A countryman was looking at some horses for sale, when a gentleman in clerical attire, and representing himself as such, applied to him to purchase a particular animal which he pointed out, saying that as a clergyman he did not like to be seen in such engagements, at the same time telling him that he would give him a sovereign for his trouble. The trick took and the young man paid £13 15s. for a horse not worth £5; which being done the clergyman was not to be found, and the purchaser had to take his bargain to himself with “all faults”.

The Popularity of the Fair

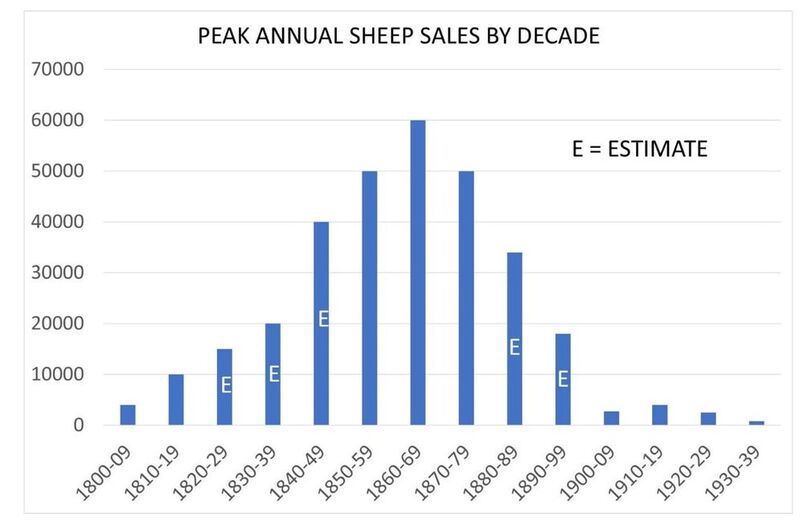

The popularity of the fair can be measured by the number of sheep put up for sale over the years, see below. Figures for some decades are not available but there are figures for the early, peak and end years. The opening of the station at Box in 1841 would have prompted an increase in numbers.

A countryman was looking at some horses for sale, when a gentleman in clerical attire, and representing himself as such, applied to him to purchase a particular animal which he pointed out, saying that as a clergyman he did not like to be seen in such engagements, at the same time telling him that he would give him a sovereign for his trouble. The trick took and the young man paid £13 15s. for a horse not worth £5; which being done the clergyman was not to be found, and the purchaser had to take his bargain to himself with “all faults”.

The Popularity of the Fair

The popularity of the fair can be measured by the number of sheep put up for sale over the years, see below. Figures for some decades are not available but there are figures for the early, peak and end years. The opening of the station at Box in 1841 would have prompted an increase in numbers.

Kingsdown Golf Club

Major William Northey was one of the six founding members of the golf club in 1880 [38] and, as he was now sole owner of the common (Edward Richard Northey having died in 1878), and he received the profits of the fair, he was in a position to allow the two to co-exist. Play was suspended for the duration of the fair. The hurdle barn is now the greenkeeper’s shed.

The End of the Fair

The funfair had ceased by 1924 when the Wiltshire Times described the fair under the headline of Shadow of a Country Holiday ... shorn of its former holiday aspect, it has become strictly utilitarian. No longer are the roads chock a block with carts and cattle, no longer are the sideshows erected… formerly the hill on Fair morning was a wonderful sight and no one for miles around missed it. It was a carnival and market in one, but little interest is taken in the event nowadays….the fair attracted many gypsies, but even they were not in such numbers as they were in former years. Sheep were now sold by auction rather than private barter.[39] The last advertisement for Kingsdown Fair was in 1945 [40] and this is assumed to be the last time it was held. It had outlived both Bradford Leigh’s stock fair which had ceased by 1914 and Lansdown Fair which had ended in 1924, although Bradford Leigh’s Pleasure Fair continued until 1964.

Major William Northey was one of the six founding members of the golf club in 1880 [38] and, as he was now sole owner of the common (Edward Richard Northey having died in 1878), and he received the profits of the fair, he was in a position to allow the two to co-exist. Play was suspended for the duration of the fair. The hurdle barn is now the greenkeeper’s shed.

The End of the Fair

The funfair had ceased by 1924 when the Wiltshire Times described the fair under the headline of Shadow of a Country Holiday ... shorn of its former holiday aspect, it has become strictly utilitarian. No longer are the roads chock a block with carts and cattle, no longer are the sideshows erected… formerly the hill on Fair morning was a wonderful sight and no one for miles around missed it. It was a carnival and market in one, but little interest is taken in the event nowadays….the fair attracted many gypsies, but even they were not in such numbers as they were in former years. Sheep were now sold by auction rather than private barter.[39] The last advertisement for Kingsdown Fair was in 1945 [40] and this is assumed to be the last time it was held. It had outlived both Bradford Leigh’s stock fair which had ceased by 1914 and Lansdown Fair which had ended in 1924, although Bradford Leigh’s Pleasure Fair continued until 1964.

References

[1] https://archives.history.ac.uk/gazetteer/gazweb2.html

[2] SG Kendall, Farming Memoirs of a West Country Yeoman, Faber & Faber, 1944 and Victor Painter, Kingsdown Memories

http://www.choghole.co.uk/victor/victor1.htm

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[4] The Gloucester Journal, 10 September 1798

[5] Bristol Archives 38797/4

[6] https://history.wiltshire.gov.uk/community/getcom.php?id=65

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 15 September 1808

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 25 May 1843

[10] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre PR/Bradford-on-Avon, Holy Trinity/77/281

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 25 May 1843

[12] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre PR/Bradford-on-Avon, Holy Trinity/77/281

[13] The Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 17 Sept 1840

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[15] The Salisbury & Winchester Journal 5 October 1835

[16] SG Kendall, Farming Memoirs of a West Country Yeoman, Faber & Faber, 1944

[17] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 9 April 1949

[18] The Hampshire Chronicle 7 August 1815

[19] Victor Painter, Kingsdown Memories http://www.choghole.co.uk/victor/victor1.htm

[20] The Wiltshire Independent 4 October 1838

[21] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 23 September 1876

[22] The Bristol Times and Mirror 1 October 1831

[23] The Cumberland Paquet 7 October 1817

[24] The Hampshire Advertiser 23 September 1876

[25] The Bristol Mercury 19 September 1878

[26] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 21 September 1878

[27] The Swindon Advertiser 19 November 1887

[28] SG Kendall, Farming Memoirs of a West Country Yeoman, Faber & Faber, 1944

[29] https://www.kingsdowngolfclub.co.uk/history

[30] The Hampshire Advertiser 14 October 1865

[31] The Berkshire Chronicle 3 October 1835

[32] The Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette 24 Sept 1868

[33] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre 1265/22

[34] The Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette 17 September 1840

[35] Victor Painter, Kingsdown Memories http://www.choghole.co.uk/victor/victor1.htm

[36] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 20 September 1924

[37] The Illustrated London News 13 August 1842

[38] https://www.kingsdowngolfclub.co.uk/history

[39] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 20 September 1924

[40] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 25 August 1945

[1] https://archives.history.ac.uk/gazetteer/gazweb2.html

[2] SG Kendall, Farming Memoirs of a West Country Yeoman, Faber & Faber, 1944 and Victor Painter, Kingsdown Memories

http://www.choghole.co.uk/victor/victor1.htm

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[4] The Gloucester Journal, 10 September 1798

[5] Bristol Archives 38797/4

[6] https://history.wiltshire.gov.uk/community/getcom.php?id=65

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 15 September 1808

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 25 May 1843

[10] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre PR/Bradford-on-Avon, Holy Trinity/77/281

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 25 May 1843

[12] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre PR/Bradford-on-Avon, Holy Trinity/77/281

[13] The Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 17 Sept 1840

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[15] The Salisbury & Winchester Journal 5 October 1835

[16] SG Kendall, Farming Memoirs of a West Country Yeoman, Faber & Faber, 1944

[17] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 9 April 1949

[18] The Hampshire Chronicle 7 August 1815

[19] Victor Painter, Kingsdown Memories http://www.choghole.co.uk/victor/victor1.htm

[20] The Wiltshire Independent 4 October 1838

[21] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 23 September 1876

[22] The Bristol Times and Mirror 1 October 1831

[23] The Cumberland Paquet 7 October 1817

[24] The Hampshire Advertiser 23 September 1876

[25] The Bristol Mercury 19 September 1878

[26] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 21 September 1878

[27] The Swindon Advertiser 19 November 1887

[28] SG Kendall, Farming Memoirs of a West Country Yeoman, Faber & Faber, 1944

[29] https://www.kingsdowngolfclub.co.uk/history

[30] The Hampshire Advertiser 14 October 1865

[31] The Berkshire Chronicle 3 October 1835

[32] The Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette 24 Sept 1868

[33] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre 1265/22

[34] The Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette 17 September 1840

[35] Victor Painter, Kingsdown Memories http://www.choghole.co.uk/victor/victor1.htm

[36] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 20 September 1924

[37] The Illustrated London News 13 August 1842

[38] https://www.kingsdowngolfclub.co.uk/history

[39] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 20 September 1924

[40] The Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 25 August 1945