|

Box's Georgian Population

Alan Payne January 2019 There was no census in Britain until 10 March 1801. The official return simply wanted a summary of numbers for each parish and it was only the unofficial compilation records that gave names of villagers. Box is fortunate that its compilation records have survived. The census recorded not only numbers but whether the population was increasing or decreasing by requiring the Overseers to give details of the number of baptisms and burials in the parish records over the previous century. The intention was to estimate if the country could feed itself despite Napoleon's plans to invade or blockade the country. The English population in 1801 was 7,754,875, Wiltshire's was 185,107. Box had only 1,165 people, a third of its present size. But these details are all from the start of the nineteenth century, 100 years after the start of the Georgian period. To find Box's earlier population, we have to reconstruct the details which do survive from those times. Right: Cicero was the model for Georgian gentleman (courtesy Wikipedia) |

Estimating Box's Population

At an earlier date, in 1628, the list of ratepayers in Box names 63 heads of households. There was one esquire, George Speke, Esq, lord of the manor of Box. Then four people who might later have been called gentlemen: George Speke's son also called George Speke, Henry Long at Ashley, Zacharias Pouer the leading person in Rudloe, and Peter Webb in the Middlehill area. The vicar, John Coren, was the next highest ratepayer. There were 30 people with a house and a little ground, called a tenement; all these people were concerned with working the land except for three millers and two clergymen.

At an earlier date, in 1628, the list of ratepayers in Box names 63 heads of households. There was one esquire, George Speke, Esq, lord of the manor of Box. Then four people who might later have been called gentlemen: George Speke's son also called George Speke, Henry Long at Ashley, Zacharias Pouer the leading person in Rudloe, and Peter Webb in the Middlehill area. The vicar, John Coren, was the next highest ratepayer. There were 30 people with a house and a little ground, called a tenement; all these people were concerned with working the land except for three millers and two clergymen.

| 1628_rates_list.doc | |

| File Size: | 84 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

To get a realistic number for the population, we need to increase the household heads for the ratepayer's wife, children and servants with the usual multiplier being five, making the rate-paying population 315, rounded as about 300. But this would totally ignore agricultural outworkers, the self-employed, the unemployed and the poor, most of whom fell outside the rates level. To get an estimate of these people in Box, we can compare the population figures in England recorded by Gregory King in 1688.[1]

|

Rank

Lords and Esquires Gentlemen Clergy & Servicemen Artisans & Shopkeepers Freeholders Farmers Labourers Cottagers & Paupers Vagrants TOTAL |

Heads

4,586 12,000 140,000 110,000 180,000 150,000 364,000 400,000 30,000 1,390,586 |

People

per Head 12.5 8 3.8 44 5.4 5 3.5 3.3 1 |

Total

57,520 96,000 528,000 484,000 980,000 750,000 1,275,000 1,300,000 30,000 5,500,520 |

%

1 2 10 9 18 13 23 23 1 |

Income pa

£640 £280 £37.10s £60 £57.10s £44 £15 £6.10s £2 £32 |

Using King's figures to calculate the proportion of gentry to the poorer levels of society, we would get an indication of perhaps 250 people who fell outside the 1628 rate details. Adding these to the 300 or so listed in the rates would give a Georgian population in Box of 550 or so at the start of the Georgian period. These people covered a huge range in society.

|

Lord of the Manor The Northey family were lords of the manor of Box and Ashley throughout the Georgian period. They were based in Epsom and Ewell, Surrey, and the Wiltshire estate was their country home. It was also an investment to be exploited as well as to raise an income from their landed estates. In 1795 an unusual sale of freehold property was made in the centre of Box which may have involved the Northeys.[2] The sale was made by Mr Spackman of Bath, who was an auctioneer and money broker, the agent of the owners. The sale particulars included the Queen's Head Inn, a house adjoining, the next house occupied by Zephania Bullock, the clockmaker, and Isaac Gingell (possibly part of Millers). The sale also included a property in Queen's Square, next door house occupied by Thomas Shill (sic), a mason, and properties adjoining including farrier's shop (possibly Pye Corner or the Queen's Head stables). There is no mention of the Northey family, nor of the landowner's name, but the extent of the land and the sale of the freehold implies the lord of the manor. |

Clergy

The ownership of the advowson (right to appoint the vicar) of Box Church changed dramatically with the end of the Speke family in the early 1700s. Control of local religious matters fell outside the authority of the lord of the manor and effectively into the hands of laymen families, first the Webb family and by the 1790s into the proprietorship of the Horlock family. Each of these appointed the person they wanted to be vicar, often a family relative, with little regard for suitability or religious following. So it was that Isaac William Webb Horlock appointed himself vicar some time before 1799 and continued until his death in December 1829 at his main home, Ashwick House, Gloucestershire. He was followed by the brief tenure of Rev Horatio Moule of Queen's College, Oxford, before Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock became vicar from 1833 until 1874.

The ownership of the advowson (right to appoint the vicar) of Box Church changed dramatically with the end of the Speke family in the early 1700s. Control of local religious matters fell outside the authority of the lord of the manor and effectively into the hands of laymen families, first the Webb family and by the 1790s into the proprietorship of the Horlock family. Each of these appointed the person they wanted to be vicar, often a family relative, with little regard for suitability or religious following. So it was that Isaac William Webb Horlock appointed himself vicar some time before 1799 and continued until his death in December 1829 at his main home, Ashwick House, Gloucestershire. He was followed by the brief tenure of Rev Horatio Moule of Queen's College, Oxford, before Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock became vicar from 1833 until 1874.

Gentleman

The role of gentleman was an important rank of society in the Georgian period, below the rank of esquire and above that of yeoman. The name derived from the French gentil homme. To belong to this society a person needed to exhibit his superior behaviour and to demonstrate his ancestry through his coat-of-arms.

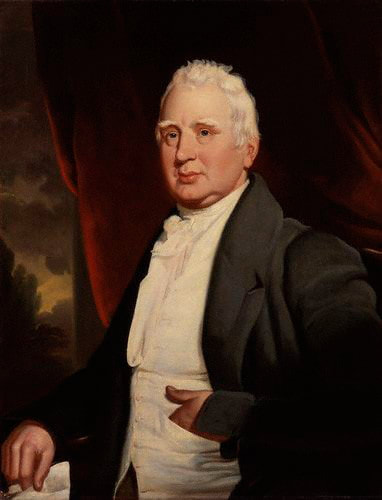

Georgian gentlemen modelled themselves on their perceived concept of ancient Greeks and Romans. As the leaders of the British Empire these men believed they were inheriting the role of empire from the classical world. They liked to show their affluence by extravagance, eating to excess, fighting duels and poor behaviour to women and the lower classes. Most were fluent in classical languages, some dressed in togas and many changed their names to Augustinian imitations. Their hero was Cicero, whose works they could read for themselves since Cicero's work De Officiis (On Moral Duties) was the second book ever printed in Europe, after the Gutenberg Bible, and his views influenced concepts of liberty in the United States and the French Revolution.

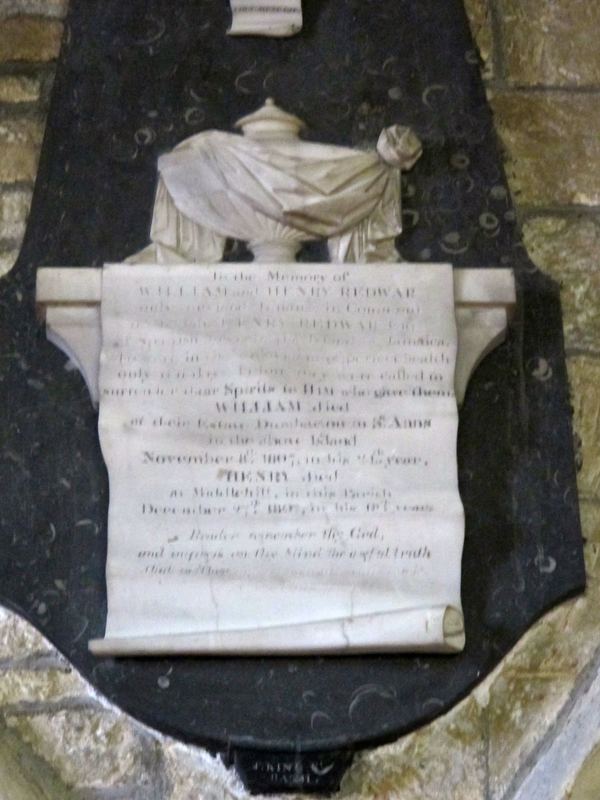

We can see that there were several Georgian gentlemen in Box by the number of classical epitaphs on the walls of St Thomas à Becket. As Bath and Bristol became increasingly attractive to the right sort of person, so Box was seen as an appropriate place to live. This was the origin of the Neate family, Bristol Merchant Venturers, who developed the properties at Middlehill.

Some people could claim to be gentry by their employment. The Jefferys family were gentry by virtue of their status as physicians at Kingsdown Mad House. Zachariah Jefferys, Practitioner in Physics, was fed up with people referring relatives as Lunaticks with no proper reason that he issued instructions for admission including that the patient's own consent be authorised by two Justices of the Peace.[3] John Jefferys, Esq, of the Crescent, Bath, put up for sale, on a decree of the High Court of Chancery, a leasehold messuage or inn, consisting of two dwelling houses, stables and outbuildings at The Old Jockey in 1789.[4] This was the origin of the name Jefferys Cottage.

Several of the great Victorian families were establishing themselves in the village, without actually making the status as gentlemen. The Pinchin family were wealthy from their ownership of Box Mill and Tobias Pinchin is mentioned in 1763.[5] Miss Vezey of Box married Edward Cottle, an eminent grazier and butcher, in 1776.[6] The Vezey family were sufficiently wealthy for Stephen Vezey, attorney-at-law of Box, to offer loans from £100 to £2,000 in 1781 upon real securities.[7] The Mullins family as schoolteachers and duty as parish clerk hovered on the verge of gentrification.

The role of gentleman was an important rank of society in the Georgian period, below the rank of esquire and above that of yeoman. The name derived from the French gentil homme. To belong to this society a person needed to exhibit his superior behaviour and to demonstrate his ancestry through his coat-of-arms.

Georgian gentlemen modelled themselves on their perceived concept of ancient Greeks and Romans. As the leaders of the British Empire these men believed they were inheriting the role of empire from the classical world. They liked to show their affluence by extravagance, eating to excess, fighting duels and poor behaviour to women and the lower classes. Most were fluent in classical languages, some dressed in togas and many changed their names to Augustinian imitations. Their hero was Cicero, whose works they could read for themselves since Cicero's work De Officiis (On Moral Duties) was the second book ever printed in Europe, after the Gutenberg Bible, and his views influenced concepts of liberty in the United States and the French Revolution.

We can see that there were several Georgian gentlemen in Box by the number of classical epitaphs on the walls of St Thomas à Becket. As Bath and Bristol became increasingly attractive to the right sort of person, so Box was seen as an appropriate place to live. This was the origin of the Neate family, Bristol Merchant Venturers, who developed the properties at Middlehill.

Some people could claim to be gentry by their employment. The Jefferys family were gentry by virtue of their status as physicians at Kingsdown Mad House. Zachariah Jefferys, Practitioner in Physics, was fed up with people referring relatives as Lunaticks with no proper reason that he issued instructions for admission including that the patient's own consent be authorised by two Justices of the Peace.[3] John Jefferys, Esq, of the Crescent, Bath, put up for sale, on a decree of the High Court of Chancery, a leasehold messuage or inn, consisting of two dwelling houses, stables and outbuildings at The Old Jockey in 1789.[4] This was the origin of the name Jefferys Cottage.

Several of the great Victorian families were establishing themselves in the village, without actually making the status as gentlemen. The Pinchin family were wealthy from their ownership of Box Mill and Tobias Pinchin is mentioned in 1763.[5] Miss Vezey of Box married Edward Cottle, an eminent grazier and butcher, in 1776.[6] The Vezey family were sufficiently wealthy for Stephen Vezey, attorney-at-law of Box, to offer loans from £100 to £2,000 in 1781 upon real securities.[7] The Mullins family as schoolteachers and duty as parish clerk hovered on the verge of gentrification.

Another way of defining status was those qualified to serve as jurors on the Wiltshire Quarter Sessions list. In 1736 there were only eleven people qualified as freeholders of land:[8] Ambrose Goddard, Gent, Nathaniel Webb, Anthony Drewett, William Jeffery of Wadswick, John Jeffery, John Ford, Anthony Lewis, William Pinchen, Jacob Bayly, Thomas Iles and William Jeffery of Ashley. These were the privileged few.

Yeomen Farmers

The middling sort of people from the Tudor period evolved into a class of residents that we call yeomen farmers. The description originated in the late medieval period as attendants in a noble's household (such as Yeomen of the Guard at the Tower of London) but it quickly evolved into farmers who owned land. This class was highly aspiring, usually working the land as a family unit. Often their homes were arranged around farmyards forming a farmstead, very suitable for animal husbandry. By investing in the business, they were able to amass some wealth and pass it on to future generations.

The century after 1670 witnessed what some have called a farming revolution in England as farmers sought to adopt best practices from their contemporaries.[9] In the 1670s John Aubrey of Kington St Michael referred to the craze for improvement when he said that it was rare before 1649 for farmers to attempt any improvement of any knowledge whatsoever, even of husbandry itself but no longer.[10] Changes came thick and fast. Agricultural Societies started 1723 -1731; numerous manuals on farming techniques appeared, such as Arthur Young's Annals of Agriculture in 45 volumes; and agricultural shows started after 1777 when Bath Agricultural Society put on the first event, now called the Bath & West Show.

The improvements covered both arable and animal husbandry. Four-field rotation of farmland and the cultivation of turnips and clover increased nutrients in the soil, instead of leaving the land fallow. The selective breeding of sheep and cattle increased meat yields and greater numbers of animals were over-wintered, rather than slaughtered in the autumn. It is generally believed that by the 1680s the population of England had stabilised at just over 5 million people and demand-led inflation petered out with the price of wheat stuck at 20% below Tudor levels.[11] Farmers focussed on reducing unit-costs to increase their profits, ideally suited to family farming units.

The branch of the Jeffery family at Wadswick were typical of the aspiring Georgian yeoman class. They were not mentioned in the 1628 rates list, so we might assume they were tenants when marked in Francis Allen's 1630 map, holding land to the north of Wadswick Lane. In 1701, William Jeffery bought Chapell Fields out of the Wadswick estate of Thomas Goddard, Gentleman at Rudloe, for £20.5s. and in his 1716 will he called himself yeoman. However, the problem of succession emerged when William died in 1738 leaving no heirs. The estate passed to his brother Thomas but he left no living heir when he died in 1765 and the property went to his nephew William Jeffery Brown.

There is some mention of other yeomen farmers but few in central Box, the exceptions being Robert Deverell, Box, and James Iddolls, Hill House Farm. The situation in the village itself offered limited opportunities of the yeoman class to acquire land as the Speke and later the Northey family were wealthy enough to refuse to sell land out of their estates.

We can also see how Georgian Box residents took up subsidiary occupations in animal husbandry, such as Samuel Rickets of Ditteridge and Robert Yells of Box both being described as fellmongers (traders in animal skins) in 1736 and Samuel Rickets of Ditteridge being referred to later as leather dresser.[12]

The middling sort of people from the Tudor period evolved into a class of residents that we call yeomen farmers. The description originated in the late medieval period as attendants in a noble's household (such as Yeomen of the Guard at the Tower of London) but it quickly evolved into farmers who owned land. This class was highly aspiring, usually working the land as a family unit. Often their homes were arranged around farmyards forming a farmstead, very suitable for animal husbandry. By investing in the business, they were able to amass some wealth and pass it on to future generations.

The century after 1670 witnessed what some have called a farming revolution in England as farmers sought to adopt best practices from their contemporaries.[9] In the 1670s John Aubrey of Kington St Michael referred to the craze for improvement when he said that it was rare before 1649 for farmers to attempt any improvement of any knowledge whatsoever, even of husbandry itself but no longer.[10] Changes came thick and fast. Agricultural Societies started 1723 -1731; numerous manuals on farming techniques appeared, such as Arthur Young's Annals of Agriculture in 45 volumes; and agricultural shows started after 1777 when Bath Agricultural Society put on the first event, now called the Bath & West Show.

The improvements covered both arable and animal husbandry. Four-field rotation of farmland and the cultivation of turnips and clover increased nutrients in the soil, instead of leaving the land fallow. The selective breeding of sheep and cattle increased meat yields and greater numbers of animals were over-wintered, rather than slaughtered in the autumn. It is generally believed that by the 1680s the population of England had stabilised at just over 5 million people and demand-led inflation petered out with the price of wheat stuck at 20% below Tudor levels.[11] Farmers focussed on reducing unit-costs to increase their profits, ideally suited to family farming units.

The branch of the Jeffery family at Wadswick were typical of the aspiring Georgian yeoman class. They were not mentioned in the 1628 rates list, so we might assume they were tenants when marked in Francis Allen's 1630 map, holding land to the north of Wadswick Lane. In 1701, William Jeffery bought Chapell Fields out of the Wadswick estate of Thomas Goddard, Gentleman at Rudloe, for £20.5s. and in his 1716 will he called himself yeoman. However, the problem of succession emerged when William died in 1738 leaving no heirs. The estate passed to his brother Thomas but he left no living heir when he died in 1765 and the property went to his nephew William Jeffery Brown.

There is some mention of other yeomen farmers but few in central Box, the exceptions being Robert Deverell, Box, and James Iddolls, Hill House Farm. The situation in the village itself offered limited opportunities of the yeoman class to acquire land as the Speke and later the Northey family were wealthy enough to refuse to sell land out of their estates.

We can also see how Georgian Box residents took up subsidiary occupations in animal husbandry, such as Samuel Rickets of Ditteridge and Robert Yells of Box both being described as fellmongers (traders in animal skins) in 1736 and Samuel Rickets of Ditteridge being referred to later as leather dresser.[12]

Wiltshire Cheese

A major part of the yeoman's success was the expansion of animal husbandry, particularly into milk production. We still sometimes divide Wiltshire into the Chalk and Cheese areas of the south and north of the county. Daniel Defoe gave a long description of the development in about 1725, saying how Wiltshire cheese was exported to Bath, Bristol, London and even the West Indies:[13]

All the lower part of this county, and also of Gloucestershire, adjoining, is full of large feeding farms, which we call dairies, and the cheese they make, as it is excellent good of its kind, so being a different kind from the Cheshire, being soft and thin, is eaten newer than that from Cheshire. Of this, a vast quantity is every week sent up to London, where, though it is called Gloucestershire cheese, yet a great part of it is made in Wiltshire.

Again, in the spring of the year, they make a vast quantity of that we call green cheese, which is a thin, and very soft cheese, resembling cream cheeses, only thicker, and very rich. These are brought to market new, and eaten so, and the quantity is so great, and this sort of cheese is so universally liked and accepted in London, that all the low, rich lands of this county, are little enough to supply the market; but then this holds only for the two first summer months of the year, May and June, or little more.

Besides this, the farmers in Wiltshire, and the part of Gloucestershire adjoining, send a very great quantity of bacon up to London, which is esteemed as the best bacon in England, Hampshire only excepted: This bacon is raised in such quantities here, by reason of the great dairies, as above, the hogs being fed with the vast quantity of whey, and skim'd milk, which so many farmers have to spare, and which must, otherwise, be thrown away.

A major part of the yeoman's success was the expansion of animal husbandry, particularly into milk production. We still sometimes divide Wiltshire into the Chalk and Cheese areas of the south and north of the county. Daniel Defoe gave a long description of the development in about 1725, saying how Wiltshire cheese was exported to Bath, Bristol, London and even the West Indies:[13]

All the lower part of this county, and also of Gloucestershire, adjoining, is full of large feeding farms, which we call dairies, and the cheese they make, as it is excellent good of its kind, so being a different kind from the Cheshire, being soft and thin, is eaten newer than that from Cheshire. Of this, a vast quantity is every week sent up to London, where, though it is called Gloucestershire cheese, yet a great part of it is made in Wiltshire.

Again, in the spring of the year, they make a vast quantity of that we call green cheese, which is a thin, and very soft cheese, resembling cream cheeses, only thicker, and very rich. These are brought to market new, and eaten so, and the quantity is so great, and this sort of cheese is so universally liked and accepted in London, that all the low, rich lands of this county, are little enough to supply the market; but then this holds only for the two first summer months of the year, May and June, or little more.

Besides this, the farmers in Wiltshire, and the part of Gloucestershire adjoining, send a very great quantity of bacon up to London, which is esteemed as the best bacon in England, Hampshire only excepted: This bacon is raised in such quantities here, by reason of the great dairies, as above, the hogs being fed with the vast quantity of whey, and skim'd milk, which so many farmers have to spare, and which must, otherwise, be thrown away.

Traders and Manufacturers

The role of the gentry became more remote as they rebuilt their properties in enclosed walls, with closed rights of way and deer and rabbit parks and estate grounds to distance themselves from ordinary people. Another type of person emerged, not dependent on the land for an income but wage-earning from trade, commerce and manufacturing. These middling sort of people became significant in Box as artisans, innkeepers, cloth workers and merchants.

We get some idea of the diversity of occupations in the village from the wills they left.[14] Of course, this reflects their wealth rather than the number of people engaged in the occupation but it does give an indication of the variety of people. Some of the earliest will-writing traders in central Box were Thomas Baily a glover 1704, John Drewett shoemaker 1711, and Jane wife of Box vicar Jacob Filkes in 1701.[15] Artisans included a sawyer in Henley, millers on the By Brook, a baker, basket-maker at Kingsdown, and carpenter at Ashley. In addition there were the families who have been discussed separately on the website: the Eyles family of cordwainers who settled in Box after 1773, the Pinchin family who ran Box Mill in 1704.

We know that Box was active in the cloth trade with references to scribbling (rough carding) and carding (combing threads and joining together short ones) and spinning (making wool into long threads), weaving (criss-crossing of the threads to make cloth). Local references include in 1680 Ambrose Dyer, Scribler ... dwelling in the said parish of Box and Jane Wiltshire: being at Bradford to learn to Spin Shoemakers' thread.[16] The references continue in 1755 when the owner of Gable Cottage, Wadswick, was James Dory, scribler. There are references in the parish records to weaving equipment in 1728: Paid Sarah Laishly for spindles 9d and Paid for a Mapp, two Spindles and Yarn 1s.[17] And those offering apprenticeships in Box included Edward White, broadweaver, in 1718 and Mary Adams, woolspinner, in 1757.[18]

Other Georgian tradesmen in Box were working in trades associated with cloth-making, such as fellmongers (dealer in sheep skins) and leather dressers, presumably working from home.[19] We should think of Box's weavers as domestic workers, perhaps living in the Market Place, where the name Glovers Lane might indicate economic activity.

There was, of course, the important Bullock family who settled in Box as clockmakers in the early 1700s. Zephaniah Bullock was recorded as living in Box in the 1710-20 period. We might imagine that it was conveniently close to Bath to attract custom from the visitors who flocked there, whilst being a much cheaper place to live than in the city. The family were recorded as clock and watchmakers in the parish records of Box church for births, deaths and marriages throughout the 1700s. There are several references to brewing in the pubs in the village. It was a profitable business and in 1806 Thomas Eyles put up to let a well-established brewery, with malt-house and dwelling house.[20] We don't know where it was situated, possibly at The Chequers as the Eyles family lived nearby. It may not have been profitable as in 1808 Thomas Phillips, maltster and baker, relinquished the lease of the premises.[21] In 1807 James Baker, cooper of Box, died in the prime of life... a dutiful son, an excellent tradesman and a sincere friend.[22]

A fascinating insight into life in Georgian Box comes with the story of Isaac Hutton, a tailor, in 1808.[23] Despite being described as industrious, he fell into debt after a long illness and was deprived of his liberty (put into debtor's prison) and his wife and three children were obliged to seek relief from Box parish. He owed £30 and an entreaty was made for donations from the humane residents of Box. Well-respected families including the Wiltshires of Box and the Cruttwells, proprietors of the Bath Chronicle, started the subscriptions with gifts of a guinea (£1.1s) but it is not known if enough money was secured to release him from prison.

The role of the gentry became more remote as they rebuilt their properties in enclosed walls, with closed rights of way and deer and rabbit parks and estate grounds to distance themselves from ordinary people. Another type of person emerged, not dependent on the land for an income but wage-earning from trade, commerce and manufacturing. These middling sort of people became significant in Box as artisans, innkeepers, cloth workers and merchants.

We get some idea of the diversity of occupations in the village from the wills they left.[14] Of course, this reflects their wealth rather than the number of people engaged in the occupation but it does give an indication of the variety of people. Some of the earliest will-writing traders in central Box were Thomas Baily a glover 1704, John Drewett shoemaker 1711, and Jane wife of Box vicar Jacob Filkes in 1701.[15] Artisans included a sawyer in Henley, millers on the By Brook, a baker, basket-maker at Kingsdown, and carpenter at Ashley. In addition there were the families who have been discussed separately on the website: the Eyles family of cordwainers who settled in Box after 1773, the Pinchin family who ran Box Mill in 1704.

We know that Box was active in the cloth trade with references to scribbling (rough carding) and carding (combing threads and joining together short ones) and spinning (making wool into long threads), weaving (criss-crossing of the threads to make cloth). Local references include in 1680 Ambrose Dyer, Scribler ... dwelling in the said parish of Box and Jane Wiltshire: being at Bradford to learn to Spin Shoemakers' thread.[16] The references continue in 1755 when the owner of Gable Cottage, Wadswick, was James Dory, scribler. There are references in the parish records to weaving equipment in 1728: Paid Sarah Laishly for spindles 9d and Paid for a Mapp, two Spindles and Yarn 1s.[17] And those offering apprenticeships in Box included Edward White, broadweaver, in 1718 and Mary Adams, woolspinner, in 1757.[18]

Other Georgian tradesmen in Box were working in trades associated with cloth-making, such as fellmongers (dealer in sheep skins) and leather dressers, presumably working from home.[19] We should think of Box's weavers as domestic workers, perhaps living in the Market Place, where the name Glovers Lane might indicate economic activity.

There was, of course, the important Bullock family who settled in Box as clockmakers in the early 1700s. Zephaniah Bullock was recorded as living in Box in the 1710-20 period. We might imagine that it was conveniently close to Bath to attract custom from the visitors who flocked there, whilst being a much cheaper place to live than in the city. The family were recorded as clock and watchmakers in the parish records of Box church for births, deaths and marriages throughout the 1700s. There are several references to brewing in the pubs in the village. It was a profitable business and in 1806 Thomas Eyles put up to let a well-established brewery, with malt-house and dwelling house.[20] We don't know where it was situated, possibly at The Chequers as the Eyles family lived nearby. It may not have been profitable as in 1808 Thomas Phillips, maltster and baker, relinquished the lease of the premises.[21] In 1807 James Baker, cooper of Box, died in the prime of life... a dutiful son, an excellent tradesman and a sincere friend.[22]

A fascinating insight into life in Georgian Box comes with the story of Isaac Hutton, a tailor, in 1808.[23] Despite being described as industrious, he fell into debt after a long illness and was deprived of his liberty (put into debtor's prison) and his wife and three children were obliged to seek relief from Box parish. He owed £30 and an entreaty was made for donations from the humane residents of Box. Well-respected families including the Wiltshires of Box and the Cruttwells, proprietors of the Bath Chronicle, started the subscriptions with gifts of a guinea (£1.1s) but it is not known if enough money was secured to release him from prison.

Agricultural Labourers

In 1734 Thomas Hazle, labourer, listed his employments which included working for William Burgis, yeoman, in the parish of Box one whole year as a covenant servant.[24] In other words, he was on a short-term contract for one year and then released. His experience was similar to James Southornwood who in 1753 recalled his life. When he was about 14 he went to Hamsum, parish of Ditteridge, where he lived with Thomas Eyles about a fortnight. Then he bargained to live with him for a whole year at the wage of £3.10s.2d which he did and received the wages. But the tone of his report changes suddenly: Has worked as a labourer only by the day or week ever since at various places.[25] One of the most decisive developments of the Georgian period was the evolution of the rural employee, wage-earning workers, paid by the day, the week or the piece.[26]

In 1734 Thomas Hazle, labourer, listed his employments which included working for William Burgis, yeoman, in the parish of Box one whole year as a covenant servant.[24] In other words, he was on a short-term contract for one year and then released. His experience was similar to James Southornwood who in 1753 recalled his life. When he was about 14 he went to Hamsum, parish of Ditteridge, where he lived with Thomas Eyles about a fortnight. Then he bargained to live with him for a whole year at the wage of £3.10s.2d which he did and received the wages. But the tone of his report changes suddenly: Has worked as a labourer only by the day or week ever since at various places.[25] One of the most decisive developments of the Georgian period was the evolution of the rural employee, wage-earning workers, paid by the day, the week or the piece.[26]

|

No longer were the majority of rural residents farming servants living as part of the household or in tied cottages. Now they were employees dependent upon the whims of their employer, liable to do his bidding or suffer dismissal and unemployment. This was no job for life and agricultural employment was usually selected at the annual hiring fair, held locally at Kingsdown.

In 1821 William Cobbett described Cricklade's agricultural labourers, The labourers seem miserably poor. Their dwellings are little better than pig-beds, and their looks indicate that their food is not nearly equal to that of a pig. Their wretched hovels are stuck upon little bits of ground on the road side, where the space has been wider than the road demanded. In many places they have not two rods to a hovel, It seems as if they had been swept off the fields by a hurricane, and had dropped and found shelter under the banks on the road side! Yesterday morning was a sharp frost; and this had set the poor creatures to digging up their little plots of potatoes. In my whole life I never saw human wretchedness equal to this : no, not even amongst the free negroes in America, who, on an average, do not work one day out of four. And this is " prosperity," is it? These, O Pitt! are the fruits of thy hellish system! However, this Wiltshire is a horrible county.[27] |

Labourers and Quarry Workers

The reduction of length of service was a constant development and, like zero-hours contracts today, was a very precarious income. In July 1760 Moses Little, labourer born in Box, worked for William Baily, a baker there, to serve him by the week at 3s a week and his diet and lodgings.[28] He remained there for two and a quarter years until Baily died, when he served Mrs Pinchen, Baily's aunt, on the same terms.

Of course, the term labourer covered a wide variety of people and wealth. Thomas Plank, labourer, was wealthy enough to own a horse in 1769, which he was tricked into selling at the Bradford fair.[29] The purchasers offered him a fictitious (bank) note signed by William Emms. The Bank of England had been started a century before to control British coinage but it didn't have authority over letters of credit issued by local banks.

After John Aubrey talked about Hazelbury Quarry in the past tense we might think that there was little stone quarrying in the Georgian period, but that wasn't so. There are numerous references to their existence throughout the period, many in connection with the accounts of the Overseers of the Poor: Rob Westcott being hurt by a Quarry and later John Bancroft when the Quarr fell in upon him.[30]

The Coroner's Bills of 1759 mention quarry accidents in Georgian Box: William Newman fell into a quarry-pit 44 feet deep and was killed; Robert Cockey was at work in a quarry and part of it fell in upon him and killed him.[31] It was repeated in the 1781 and 1791 records: Box Quarries. A man whose name appeared to be Sillman seen going along the road and soon after found dead, and William Gibbons killed by a great weight of stone falling on him at a quarry in Box.[32]

At the end of the Georgian period there are various quarrymen listed as wealthy enough to leave a will, including Charles Barrett a freestone mason in 1814. Families were involved in the business and there is mention of the death of James Rawlings free-stone mason in 1809 and William Rawlings, a stonecutter in 1817, was wealthy enough to leave a will. In 1828 a fourteen year-old boy, Henry Aust, was moving the sled from the mouth of Mr Brewer's quarry at Box Hill when he fell in and broke his neck.[33]

We can see how the population of the village was evolving into that which epitomises our typical Victorian breakdown with family farm units, greater stone quarrying and a diversity of tradesmen and services. But the main difference was the number of people in the village, in Georgian times a fraction of the Victorian population.

The reduction of length of service was a constant development and, like zero-hours contracts today, was a very precarious income. In July 1760 Moses Little, labourer born in Box, worked for William Baily, a baker there, to serve him by the week at 3s a week and his diet and lodgings.[28] He remained there for two and a quarter years until Baily died, when he served Mrs Pinchen, Baily's aunt, on the same terms.

Of course, the term labourer covered a wide variety of people and wealth. Thomas Plank, labourer, was wealthy enough to own a horse in 1769, which he was tricked into selling at the Bradford fair.[29] The purchasers offered him a fictitious (bank) note signed by William Emms. The Bank of England had been started a century before to control British coinage but it didn't have authority over letters of credit issued by local banks.

After John Aubrey talked about Hazelbury Quarry in the past tense we might think that there was little stone quarrying in the Georgian period, but that wasn't so. There are numerous references to their existence throughout the period, many in connection with the accounts of the Overseers of the Poor: Rob Westcott being hurt by a Quarry and later John Bancroft when the Quarr fell in upon him.[30]

The Coroner's Bills of 1759 mention quarry accidents in Georgian Box: William Newman fell into a quarry-pit 44 feet deep and was killed; Robert Cockey was at work in a quarry and part of it fell in upon him and killed him.[31] It was repeated in the 1781 and 1791 records: Box Quarries. A man whose name appeared to be Sillman seen going along the road and soon after found dead, and William Gibbons killed by a great weight of stone falling on him at a quarry in Box.[32]

At the end of the Georgian period there are various quarrymen listed as wealthy enough to leave a will, including Charles Barrett a freestone mason in 1814. Families were involved in the business and there is mention of the death of James Rawlings free-stone mason in 1809 and William Rawlings, a stonecutter in 1817, was wealthy enough to leave a will. In 1828 a fourteen year-old boy, Henry Aust, was moving the sled from the mouth of Mr Brewer's quarry at Box Hill when he fell in and broke his neck.[33]

We can see how the population of the village was evolving into that which epitomises our typical Victorian breakdown with family farm units, greater stone quarrying and a diversity of tradesmen and services. But the main difference was the number of people in the village, in Georgian times a fraction of the Victorian population.

Paupers, Rogues and Vagabonds

Since 1598 this group of people were to be whipped and sent to their own settlement parish if they were aged over 7 years, although they were spared the whipping if pregnant or infirm.[34] After 1662 removal of vagrants was extended to include almost any stranger without a certificate from the parish of settlement accepting financial liability.[35] They were issued with a passport which they were obliged to show and accompanied by the Tythingman through each parish area. At times Box Vestry appears to have been generous in making donations to assist strangers passing through the parish with a pass.[36] But, of course, it was in the ratepayers' interest to move people on to the next parish as soon as possible.

Ann Smith, wife of a soldier was apprehended in Great Neston, Cheshire in 1755 as a Rogue and Vagabond wandering and begging there.[37] Instructions were issued to convey her from parish to parish from Chester all the way back to Box, her legal place of settlement. Foraging still played a part in the lives of these people and in 1769 the Northey family notified the village that they would prosecute people found angling.[38] It had to be repeated later and in 1807 William Northey put an advertisement in the local newspaper about Fish in Box Brook having been lately very much destroyed by people with nets and anglers.[39]

After about 1795 wages appear to have fallen sharply and there was an increase in the payments made by local authorities to top up earnings especially during winter times. Of course, the cost of this so-called Speenhamland system was borne by local ratepayers who began to resent the cost of the payments, leading to various Victorian reforms of Union Workhouses and Mental Homes.

Since 1598 this group of people were to be whipped and sent to their own settlement parish if they were aged over 7 years, although they were spared the whipping if pregnant or infirm.[34] After 1662 removal of vagrants was extended to include almost any stranger without a certificate from the parish of settlement accepting financial liability.[35] They were issued with a passport which they were obliged to show and accompanied by the Tythingman through each parish area. At times Box Vestry appears to have been generous in making donations to assist strangers passing through the parish with a pass.[36] But, of course, it was in the ratepayers' interest to move people on to the next parish as soon as possible.

Ann Smith, wife of a soldier was apprehended in Great Neston, Cheshire in 1755 as a Rogue and Vagabond wandering and begging there.[37] Instructions were issued to convey her from parish to parish from Chester all the way back to Box, her legal place of settlement. Foraging still played a part in the lives of these people and in 1769 the Northey family notified the village that they would prosecute people found angling.[38] It had to be repeated later and in 1807 William Northey put an advertisement in the local newspaper about Fish in Box Brook having been lately very much destroyed by people with nets and anglers.[39]

After about 1795 wages appear to have fallen sharply and there was an increase in the payments made by local authorities to top up earnings especially during winter times. Of course, the cost of this so-called Speenhamland system was borne by local ratepayers who began to resent the cost of the payments, leading to various Victorian reforms of Union Workhouses and Mental Homes.

References

[1] Quoted in Peter Mathias, The First Industrial Revolution: Economic History of Britain, 1700-1914, Methuen & Co, 1969, p.24

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 14 May 1795

[3] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 1 June 1769

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 9 July 1789

[5] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 June 1763

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 22 February 1776

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 1 March 1781

[8] There are disagreements about dates: Keith Wrightson, Early Modern England, Yale University, iTunesU, Chapter 12 argued for a revolution 1650 - 1750, whereas GE Mingay and JD Chambers dated it later in The Agricultural Revolution 1750 – 1880, Batsford. 1966

[9] Wiltshire Quarter Sessions and Assizes, 1736, Vol XI, Freeholder Book, 1736, Wiltshire History Centre

[10] John Aubrey, Naturall Historie, published 1847, Wiltshire Topographical Society

[11] Keith Wrightson, Early Modern England, Yale University, iTunesU, Chapter 23

[12] JPM Fowle, Wilts Quarter Sessions and Assizes 1736, 1755, Wiltshire Record Society, p.28 and 34

[13] http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/travellers/Defoe/16

[14] Courtesy Claire Dimond-Mills based on her researches in Wiltshire History Centre

[15] Wills recorded in Wiltshire History Centre, Chippenham

[16] A Shaw Mellor, Box Parish Records: Sidelights on Life in a Wiltshire Village, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLVII, p.346 and 352

[17] A Shaw Mellor, Extracts from the Accounts of the Overseers of Box, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society,

Vol XLV , p.344

[18] N J Williams, Wiltshire Apprentices and their Masters 1710-1760, 1961, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 17, p.6 and 141

[19] JPM Fowle, Wiltshire Quarter Sessions and Assizes 1736, 1755, Wiltshire Record Society Vol 11, p.28 and 34

[20] The Bath Chronicle, 11 December 1806

[21] The Bath Chronicle, 8 September 1808

[22] The Bath Chronicle, 9 July 1807

[23] The Bath Chronicle, 21 April 1808

[24] Phyllis Hembry, Calendar of Bradford-on-Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98, 1990, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 46, p.3

[25] Phyllis Hembry, Calendar of Bradford-on-Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98, 1990, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 46, p.11

[26] EJ Hobsbawm and George Rudé, Captain Swing, 1969, Penguin Books, p.18

[27] https://archive.org/stream/ruralrides01cobb/ruralrides01cobb_djvu.txt

[28] Phyllis Hembry, Calendar of Bradford-on-Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98, 1990, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 46, p.21

[29] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 1 June 1769

[30] A Shaw Mellor, Box Parish Records: Sidelights on Life in a Wiltshire Village, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLVII, p.346-7

[31] RF Hunnisett, Coroners' Bills, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol.36, 1981, p.14 and 16

[32] RF Hunnisett, Coroners' Bills, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol.36, p.79 and 112

[33] The Bath Chronicle, 12 November 1828

[34] Paul Slack, Poverty in Early Stuart Salisbury, 1975, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 31, p. 1-2

[35] Phyllis Hembry, Calendar of Bradford-on-Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98, 1990, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 46, p.xiv

[36] A Shaw Mellor, Box Parish Records: Sidelights on Life in a Wiltshire Village, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLVII, p.347

[37] A Shaw Mellor, Box Parish Records: Sidelights on Life in a Wiltshire Village, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLVII, p.354

[38] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 18 May 1769

[39] The Bath Chronicle, 9 July 1807

[1] Quoted in Peter Mathias, The First Industrial Revolution: Economic History of Britain, 1700-1914, Methuen & Co, 1969, p.24

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 14 May 1795

[3] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 1 June 1769

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 9 July 1789

[5] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 June 1763

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 22 February 1776

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 1 March 1781

[8] There are disagreements about dates: Keith Wrightson, Early Modern England, Yale University, iTunesU, Chapter 12 argued for a revolution 1650 - 1750, whereas GE Mingay and JD Chambers dated it later in The Agricultural Revolution 1750 – 1880, Batsford. 1966

[9] Wiltshire Quarter Sessions and Assizes, 1736, Vol XI, Freeholder Book, 1736, Wiltshire History Centre

[10] John Aubrey, Naturall Historie, published 1847, Wiltshire Topographical Society

[11] Keith Wrightson, Early Modern England, Yale University, iTunesU, Chapter 23

[12] JPM Fowle, Wilts Quarter Sessions and Assizes 1736, 1755, Wiltshire Record Society, p.28 and 34

[13] http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/travellers/Defoe/16

[14] Courtesy Claire Dimond-Mills based on her researches in Wiltshire History Centre

[15] Wills recorded in Wiltshire History Centre, Chippenham

[16] A Shaw Mellor, Box Parish Records: Sidelights on Life in a Wiltshire Village, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLVII, p.346 and 352

[17] A Shaw Mellor, Extracts from the Accounts of the Overseers of Box, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society,

Vol XLV , p.344

[18] N J Williams, Wiltshire Apprentices and their Masters 1710-1760, 1961, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 17, p.6 and 141

[19] JPM Fowle, Wiltshire Quarter Sessions and Assizes 1736, 1755, Wiltshire Record Society Vol 11, p.28 and 34

[20] The Bath Chronicle, 11 December 1806

[21] The Bath Chronicle, 8 September 1808

[22] The Bath Chronicle, 9 July 1807

[23] The Bath Chronicle, 21 April 1808

[24] Phyllis Hembry, Calendar of Bradford-on-Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98, 1990, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 46, p.3

[25] Phyllis Hembry, Calendar of Bradford-on-Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98, 1990, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 46, p.11

[26] EJ Hobsbawm and George Rudé, Captain Swing, 1969, Penguin Books, p.18

[27] https://archive.org/stream/ruralrides01cobb/ruralrides01cobb_djvu.txt

[28] Phyllis Hembry, Calendar of Bradford-on-Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98, 1990, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 46, p.21

[29] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 1 June 1769

[30] A Shaw Mellor, Box Parish Records: Sidelights on Life in a Wiltshire Village, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLVII, p.346-7

[31] RF Hunnisett, Coroners' Bills, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol.36, 1981, p.14 and 16

[32] RF Hunnisett, Coroners' Bills, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol.36, p.79 and 112

[33] The Bath Chronicle, 12 November 1828

[34] Paul Slack, Poverty in Early Stuart Salisbury, 1975, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 31, p. 1-2

[35] Phyllis Hembry, Calendar of Bradford-on-Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98, 1990, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 46, p.xiv

[36] A Shaw Mellor, Box Parish Records: Sidelights on Life in a Wiltshire Village, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLVII, p.347

[37] A Shaw Mellor, Box Parish Records: Sidelights on Life in a Wiltshire Village, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLVII, p.354

[38] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 18 May 1769

[39] The Bath Chronicle, 9 July 1807