|

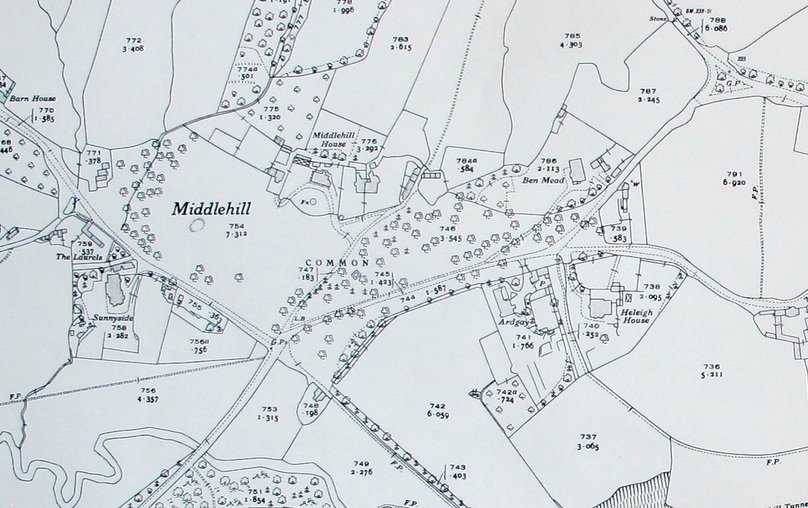

Middlehill House and

Its Remarkable Owners Original house research by Sue Rowell December 2015 Few houses have had as many make-overs and important owners as Middlehill House in the north of the parish. Yet its story has rarely been told in detail until now when we have been allowed access to the property and memories of its owners. Right: The Regency exterior hides an earlier front (courtesy Carol Payne) |

Earliest Building

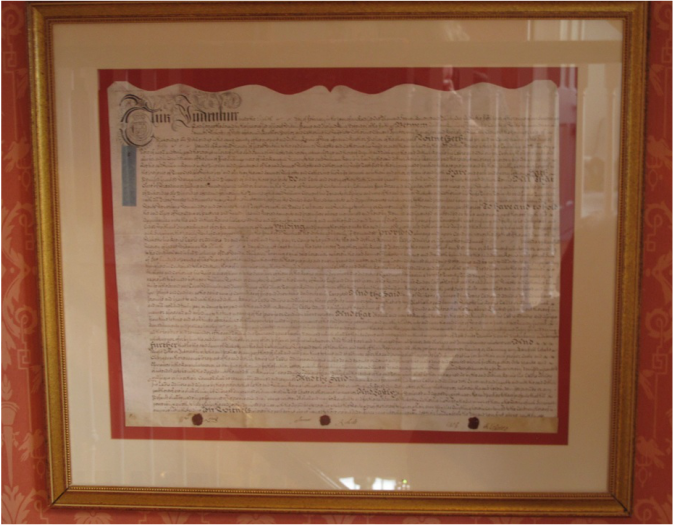

The area is first recorded in 1558 when there is a reference to Myddlehyll.[1] An indenture (legal contract) dated 8 February 1731 when the land was sold on a thousand year lease by William Lewis and Samuel Ricketts (both leather drapers) and Samuel's wife Catherine Ricketts (nee Clement) to the ownership of Arthur Lewis for the sum of £50. We don't know much about these people but the document tells of a fascinating period in English history, the fifth year of the reign of George II, the last monarch to be born and brought up abroad (in Hanover, Germany) and the last to lead an army in person. To put it into historical context, it records a land transaction a few years before the rebellion by Bonnie Prince Charlie. A transcription of the indenture is given in the Appendix below.

The indenture is a nightmare to read but it tells of the early days of promissory notes (rather than Bank of England currency) with references to lawful currency of Great Britain and provisions for the possibility of the default of the Bond of Obligation given by gentlemen of the Middle and Inner Temple, London, who funded the mortgage.

The area is first recorded in 1558 when there is a reference to Myddlehyll.[1] An indenture (legal contract) dated 8 February 1731 when the land was sold on a thousand year lease by William Lewis and Samuel Ricketts (both leather drapers) and Samuel's wife Catherine Ricketts (nee Clement) to the ownership of Arthur Lewis for the sum of £50. We don't know much about these people but the document tells of a fascinating period in English history, the fifth year of the reign of George II, the last monarch to be born and brought up abroad (in Hanover, Germany) and the last to lead an army in person. To put it into historical context, it records a land transaction a few years before the rebellion by Bonnie Prince Charlie. A transcription of the indenture is given in the Appendix below.

The indenture is a nightmare to read but it tells of the early days of promissory notes (rather than Bank of England currency) with references to lawful currency of Great Britain and provisions for the possibility of the default of the Bond of Obligation given by gentlemen of the Middle and Inner Temple, London, who funded the mortgage.

John Neat

Middlehill House first came to prominence in 1769 when John Neat of Cheney Court placed a newspaper advertisement, To Be Lett (sic) and entered upon immediately, a New-built house, four rooms on a floor, with a stable, garden and orchard, also a piece of old building adjoining, and about four acres of good pasture ground if required; situate at Middle-Hill, in the parish of Box, Wilts. A Coach house will be built if desired.[2]

In 1770 the house was again advertised after the coach house had been built and five additional acres were offered.[3] Tragedy struck the family when in 1786 John Neat, the younger, was crossing a rivulet on horseback between Frome and Maiden Bradley, he was unfortunately drowned to the great grief of his parents and relations. He was a young man of unblemished character.[4]

John Neat, senior, made his money as a member of the Bristol Merchant Venturers Society who controlled trade into Bristol Port. He reputedly made a fortune in the years around 1800 when the Society broke Napoleon's blockade to bring candle tallow (wicks) in from the Baltic. He used his money to transform the front of Middlehill House.

John Neat, senior, died in 1808 and the house again went on the market to let, a large, convenient house with every requisite office.[5] But that wasn't the end of the story. On 5 May 1844 his grandson, also John Neat, died at Middlehill and the 1851 and 1861 census records his wife Elizabeth Neat at Middlehill between Spa House and the family of Struan Robertson at ByBrook House.[6] Elizabeth, who was born in 1781, continued to live there and her death on 6 May 1868 was recorded as, at Middle-Hill Box, Elizabeth, relict of John Neat, Esq, in her 94th year.[7]

Middlehill House first came to prominence in 1769 when John Neat of Cheney Court placed a newspaper advertisement, To Be Lett (sic) and entered upon immediately, a New-built house, four rooms on a floor, with a stable, garden and orchard, also a piece of old building adjoining, and about four acres of good pasture ground if required; situate at Middle-Hill, in the parish of Box, Wilts. A Coach house will be built if desired.[2]

In 1770 the house was again advertised after the coach house had been built and five additional acres were offered.[3] Tragedy struck the family when in 1786 John Neat, the younger, was crossing a rivulet on horseback between Frome and Maiden Bradley, he was unfortunately drowned to the great grief of his parents and relations. He was a young man of unblemished character.[4]

John Neat, senior, made his money as a member of the Bristol Merchant Venturers Society who controlled trade into Bristol Port. He reputedly made a fortune in the years around 1800 when the Society broke Napoleon's blockade to bring candle tallow (wicks) in from the Baltic. He used his money to transform the front of Middlehill House.

John Neat, senior, died in 1808 and the house again went on the market to let, a large, convenient house with every requisite office.[5] But that wasn't the end of the story. On 5 May 1844 his grandson, also John Neat, died at Middlehill and the 1851 and 1861 census records his wife Elizabeth Neat at Middlehill between Spa House and the family of Struan Robertson at ByBrook House.[6] Elizabeth, who was born in 1781, continued to live there and her death on 6 May 1868 was recorded as, at Middle-Hill Box, Elizabeth, relict of John Neat, Esq, in her 94th year.[7]

Situation of the House

Built before the creation of the A4 road joining Box and Bath, the house was originally on one of the main routes to London. In 1826 the house was advertised to let, unfurnished and described as: Middle-Hill House with Cottage, Coach house, Stable and excellent Garden; the situation delightful, and air salubrious; 5 miles from Bath, on the London road; and half a mile from Box.[8]

Built before the creation of the A4 road joining Box and Bath, the house was originally on one of the main routes to London. In 1826 the house was advertised to let, unfurnished and described as: Middle-Hill House with Cottage, Coach house, Stable and excellent Garden; the situation delightful, and air salubrious; 5 miles from Bath, on the London road; and half a mile from Box.[8]

|

By the time that the railway had been built, the location was described differently and in 1845 was advertised as, situated opposite the Box Station ... within ten minutes by Railway and five miles by road from Bath.[9]

The house was considered to be isolated from the village and required to be self- sufficient, including an army of servants as befitted the wealth and status of the owner. In the grounds it had its own cemetery of unknown age and the obligatory back staircase gives access to the servants' quarters, away from the view of the owners. One of the upstairs bedrooms has a window scratched with the name Ruth, presumably one of the female domestics who lived communally in the top floor dormitory. |

Natural Water Springs

One of the reasons for the location of the building was the convenient water supply. In 1888 the house was occupied by William J Brown, a member of the Bath and West Society, described as a man whose integrity and capacity were beyond question.[10] He had retired from farming 700 acres at Wadswick and invested his wealth into Middlehill.

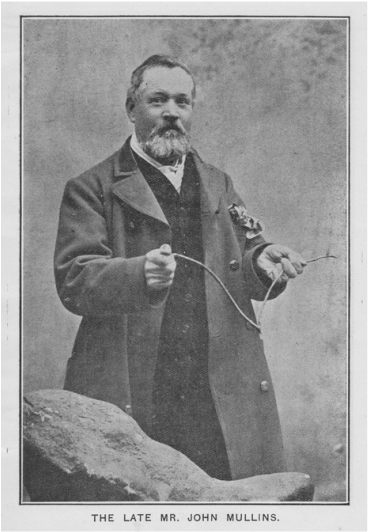

He recounted a fascinating story of water divining by Mr Mullins of Ashley which took place in Middlehill House. To test Mr Mullins, three sovereign coins had been placed under the Turkish carpet without his knowledge and the dowsing rod quickly found their presence. Later Mr Brown was a champion of Mr Mullin's work.

The house still stands over a water course and the basement is periodically flooded (particularly after it has snowed) with a stream going straight through it which flows out, then clears and dries out.

One of the reasons for the location of the building was the convenient water supply. In 1888 the house was occupied by William J Brown, a member of the Bath and West Society, described as a man whose integrity and capacity were beyond question.[10] He had retired from farming 700 acres at Wadswick and invested his wealth into Middlehill.

He recounted a fascinating story of water divining by Mr Mullins of Ashley which took place in Middlehill House. To test Mr Mullins, three sovereign coins had been placed under the Turkish carpet without his knowledge and the dowsing rod quickly found their presence. Later Mr Brown was a champion of Mr Mullin's work.

The house still stands over a water course and the basement is periodically flooded (particularly after it has snowed) with a stream going straight through it which flows out, then clears and dries out.

The cellar is a fascinating area and it hides a butchering area where animals (probably pigs and chickens) were kept alive until they were needed (below left), their bodies being bled on hooks in the ceiling until needed for consumption (below right).

Photos courtesy Carol Payne.

Photos courtesy Carol Payne.

Rebuilding the House

The reference in the 1769 advertisement above to an old building adjoining perhaps relates to an even earlier incarnation of the property. The different styles at the rear of the property indicate that the left wing of the house is much earlier than the front facade which was extended and Georgianised in the mid-1700s (below right).[11] This seems to have been confirmed when roof repairs in the 2010s showed the existence of an earlier roof structure under the visible roof line.

Nowadays we regard the property as Georgian and admire its style and gracefulness. The staircase which joins the old and the new property is elegant and built to impress visitors, with its view up and down four floors (below right). It was a self contained area and visitors were kept well away from the servants' back stairs in the old part of the house. Photos courtesy Carol Payne.

The reference in the 1769 advertisement above to an old building adjoining perhaps relates to an even earlier incarnation of the property. The different styles at the rear of the property indicate that the left wing of the house is much earlier than the front facade which was extended and Georgianised in the mid-1700s (below right).[11] This seems to have been confirmed when roof repairs in the 2010s showed the existence of an earlier roof structure under the visible roof line.

Nowadays we regard the property as Georgian and admire its style and gracefulness. The staircase which joins the old and the new property is elegant and built to impress visitors, with its view up and down four floors (below right). It was a self contained area and visitors were kept well away from the servants' back stairs in the old part of the house. Photos courtesy Carol Payne.

Colonel JDB Erskine

Around the time of the First World War, the house was owned by Lieutenant-Colonel John David Beveridge Erskine (usually known by the initials JDB).[12] He had served in the Boer War and retired from service with the Manchester Regiment in 1911. At the outbreak of the Great War he volunteered for service in the Light Infantry in France and Salonika receiving the Croix de Guerre with Palm and was awarded a DSO by the King in 1919.[13] Afterwards he was a leading figure in the local British Legion branch.

Around the time of the First World War, the house was owned by Lieutenant-Colonel John David Beveridge Erskine (usually known by the initials JDB).[12] He had served in the Boer War and retired from service with the Manchester Regiment in 1911. At the outbreak of the Great War he volunteered for service in the Light Infantry in France and Salonika receiving the Croix de Guerre with Palm and was awarded a DSO by the King in 1919.[13] Afterwards he was a leading figure in the local British Legion branch.

|

He died aged 58 in 1926.[14] His will summed up the man with bequests left as a reminder of our duty and privilege always to serve our Sovereign and country.[15]

The family stayed in the house after Colonel Erskine's death and was there in 1933 for the engagement of Elizabeth, the younger daughter.[16] In 1935 Mrs Erskine allowed forty Bath Cadets to camp in the grounds, after which they marched to Box Parish Church for inspection by Colonel LD Naper. At the end of the weekend, the cadets gave Mrs Erskine three rousing cheers which echoed across the valley.[17] Right: Photo of the house and Middlehill Common (courtesy Sue Rowell) |

Second World War

The property was again used for military purposes when it was commandeered as officer accommodation in 1939. During the war, and before her marriage, Mrs Hucker lived in the attic and worked as a domestic maid. She continued to live in the house after her marriage to the house gardener, who lived in the next-door Middlehill Cottage. The soldiers based in the house cut a path from the cottage to the house to allow them easier access. There are still remains of Nissan huts in the rockery of Middlehill House garden.

The property was again used for military purposes when it was commandeered as officer accommodation in 1939. During the war, and before her marriage, Mrs Hucker lived in the attic and worked as a domestic maid. She continued to live in the house after her marriage to the house gardener, who lived in the next-door Middlehill Cottage. The soldiers based in the house cut a path from the cottage to the house to allow them easier access. There are still remains of Nissan huts in the rockery of Middlehill House garden.

Miss Kathleen Harper

Perhaps the most significant owner in modern times was Miss Kathleen Harper, an amazing character and public servant, who is one of our particular heroines. She was a native of Bath but moved to Middlehill House in June 1949.[18] There are numerous stories about her lack of driving skills: that she ran into her sister who was opening the gate, and that she couldn't reach the pedals when she had a Bentley car. They reflect the affinity the village had with her and she adopted the area for her most treasured causes, the welfare of children.

Miss Harper was no simple do-gooder. Her interests included the English Folk Dance Society where she served as secretary, vice president and later president throughout the 1920s and up to 1937 and organised an annual festival at Longleat. She enthused others in the area such as Mr and the Hon Mrs Shaw Mellor in Box and together they put on weekly classes of instruction[19] and took the lead in arranging a West of England Festival in 1935.[20]

She was a leading member of the local Conservative Society, a supporter of animal welfare and the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA), several times acting as judge in local shows, especially that at Larkhall. She belonged to the World Peace Union of 1928.

Perhaps the most significant owner in modern times was Miss Kathleen Harper, an amazing character and public servant, who is one of our particular heroines. She was a native of Bath but moved to Middlehill House in June 1949.[18] There are numerous stories about her lack of driving skills: that she ran into her sister who was opening the gate, and that she couldn't reach the pedals when she had a Bentley car. They reflect the affinity the village had with her and she adopted the area for her most treasured causes, the welfare of children.

Miss Harper was no simple do-gooder. Her interests included the English Folk Dance Society where she served as secretary, vice president and later president throughout the 1920s and up to 1937 and organised an annual festival at Longleat. She enthused others in the area such as Mr and the Hon Mrs Shaw Mellor in Box and together they put on weekly classes of instruction[19] and took the lead in arranging a West of England Festival in 1935.[20]

She was a leading member of the local Conservative Society, a supporter of animal welfare and the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA), several times acting as judge in local shows, especially that at Larkhall. She belonged to the World Peace Union of 1928.

She was asked to serve as a magistrate in Bath in 1942 which she did for a number of years.[21] After the Second World War she stood for the Walcot North ward in Bath and began a further career as a city councillor.[22] This phase of her life culminated in 1950 when she became the first female Mayor of Bath, serving with her sister Dorothy as Lady Mayor. Residents remember how she used to park her Rover car right outside the Guildhall in the city centre.

Locally she virtually ran Ditteridge Church dealing with the upkeep of the fabric and insisting on flowers in vases rather than jam jars. Both she and her sister were later buried in Ditteridge churchyard and a bank of conifers planted for them. But she will chiefly be remembered for her remarkable work for the Church of England's Waifs and Strays Society, which she championed locally for over a third of a century and showed just what could be achieved by a single person with hard work and persistence.

Locally she virtually ran Ditteridge Church dealing with the upkeep of the fabric and insisting on flowers in vases rather than jam jars. Both she and her sister were later buried in Ditteridge churchyard and a bank of conifers planted for them. But she will chiefly be remembered for her remarkable work for the Church of England's Waifs and Strays Society, which she championed locally for over a third of a century and showed just what could be achieved by a single person with hard work and persistence.

Waifs and Strays Society

The Church of England's Waifs and Strays Society was started to care for young women and children after the Great War.

Miss Harper was involved with the Society as early as 1919 when 2,000 children of dead and wounded servicemen were cared for, including a bed at St Martin's Home for Crippled Children in Woking, Surrey.[23] A report in 1920 referred to the increased activity of the Bath branch due to the zealous administration of Miss Harper, aged 20.

Her imagination to raise money for the society and her ability to publicise its work was boundless and her enthusiasm was infectious.[24] In 1923 the group started putting on an annual historic masque (dance) and fair to fundraise over three days starting with an Elizabethan-themed event, selling from stalls in the Assembly Hall, Bath, which had been dressed as an Elizabethan village, and attended by many visitors dressed in period costume, including Ye Thrifty Housewives of Bathwick Hill.[25] It was a tremendous success, raising over £1,000.

Later events included a Stuart Fair and Masque (a restoration pastorale in Old Chelsea featuring a visit from King Charles and Queen Catherine) depicting a day in 1676. It attracted stallholder support from nobility throughout the west country. The report of the event took over a whole page in the local newspaper, a remarkable achievement, and allowed eight additional cots to be endowed.[26]

The Church of England's Waifs and Strays Society was started to care for young women and children after the Great War.

Miss Harper was involved with the Society as early as 1919 when 2,000 children of dead and wounded servicemen were cared for, including a bed at St Martin's Home for Crippled Children in Woking, Surrey.[23] A report in 1920 referred to the increased activity of the Bath branch due to the zealous administration of Miss Harper, aged 20.

Her imagination to raise money for the society and her ability to publicise its work was boundless and her enthusiasm was infectious.[24] In 1923 the group started putting on an annual historic masque (dance) and fair to fundraise over three days starting with an Elizabethan-themed event, selling from stalls in the Assembly Hall, Bath, which had been dressed as an Elizabethan village, and attended by many visitors dressed in period costume, including Ye Thrifty Housewives of Bathwick Hill.[25] It was a tremendous success, raising over £1,000.

Later events included a Stuart Fair and Masque (a restoration pastorale in Old Chelsea featuring a visit from King Charles and Queen Catherine) depicting a day in 1676. It attracted stallholder support from nobility throughout the west country. The report of the event took over a whole page in the local newspaper, a remarkable achievement, and allowed eight additional cots to be endowed.[26]

|

Miss Harper was very well-connected and used her influence to great effect. She was the granddaughter of William Adair Bruce, barrister and director of GWR, who built and lived at Ashley House until his death in 1893.[27] Viscountess French (wife of Field-Marshall French, Earl of Ypres) opened the 1924 fair, Lady Peirse became a committee member and even Viscount French (son of the Field Marshall) performed in his wife's play in a 1932 Waifs and Strays fundraising event, playing the part of a penniless Baronet.[28]

In 1930 the Society had bought a home for Waifs and Strays at Sunnyside, Box and Miss Harper's association with the village became firmer. The number of Box ladies who manned stalls for the Bath Masques and Fairs grew considerably and reads like a Who's Who of Box village: Mrs George Hill (stationery stall), Miss Joyce Kidston (groceries), Mrs Daniell (dairy produce), Mrs Hemmings (Everything for my Lady), and so on.[29] The Second World War put additional pressure on orphaned children and also on funding available. Miss Harper urged Bath City Council to put funds into starting its own home, rather than use St Martin's Hospital.[30] It never happened and the facilities at Holy Innocents in Box were expanded with 15 cots specifically for Bath children.[31] |

And the final word must go to Miss Harper herself. You can get a sense of the woman from a case she heard as a magistrate in 1947 involving the abuse of a 9-year old girl by an Admiralty Policeman: This is one of the gravest offences you could have committed. It is our duty as magistrates to protect the public and especially young children. We can't tell you how disgusted we are with what we have heard and we have unanimously decided to inflict the maximum penalty.[32]

|

Kathleen and Dorothy Harper in Box

Kathleen and her sister, Dorothy, rattled around in Middlehill Hill House. Despite their powerful administration ability, they remained private people and there are few photographs of them. They busied themselves with running the house, re-designing the garden with five gardeners on duty and in enjoying their relaxation time. Dorothy Alice M Harper was born 14 February1902 and passed away in 1970. Kathleen Agnes M Harper, born on 9 November 1899, moved to Box in 1949 and died in 1983. Right: Courtesy Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 10 June 1950 |

In more recent times, the house was sold to Mr Norman who owned Spafax (Bath Spa Factors), an international television and marketing company in the 1980s based at Cheney Court and Box Mill.

Appendix

Indenture dated 8 February 1731

Indenture dated 8 February 1731

| indenture_8_february_1731.pdf | |

| File Size: | 47 kb |

| File Type: | |

References

[1] PM Slocombe, 1984, Wiltshire History Centre recording a reference by Glover, The Placenames of Wiltshire.

[2] The Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 29 June 1769

[3] The Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 28 June 1770

[4] The Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 12 January 1786

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 2 June 1808

[6] The Wiltshire Independent, 9 May 1844

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 7 May 1868

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 25 May 1826

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 26 June 1845

[10] Recited in The Bath Chronicle, 2 February 1918

[11] This process seems to have been often repeated including restoration work in the mid 1800s (said by Historic Buildings Listing to be 1830-40 and in 1946 when colonnades were installed in the side view to the garden)

[12] The property has several times been occupied by military personnel, in 1881 by Major-General JE Hope and his wife (The Bath Chronicle 30 June 1881).

[13] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 14 June 1919

[14] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 13 May 1926

[15] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 3 July 1926

[16] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 7 January 1933

[17] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 June 1935

[18] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 4 June 1949

[19] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 29 October 1932

[20] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 October 1935

[21] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 17 January 1942

[22] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 8 December 1945

[23] The Bath Chronicle, 11 January 1919

[24] The Bath Chronicle, 15 January 1921

[25] The Bath Chronicle, 20 January 1923 and 21 April 1923

[26] The Bath Chronicle and Herald, 6 July 1935 and 30 November 1935

[27] The Bath Chronicle, 8 September 1923

[28] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 30 April 1932

[29] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 24 July 1937

[30] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 1 December 1945

[31] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 20 September 1947

[32] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 23 August 1947

[1] PM Slocombe, 1984, Wiltshire History Centre recording a reference by Glover, The Placenames of Wiltshire.

[2] The Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 29 June 1769

[3] The Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 28 June 1770

[4] The Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 12 January 1786

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 2 June 1808

[6] The Wiltshire Independent, 9 May 1844

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 7 May 1868

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 25 May 1826

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 26 June 1845

[10] Recited in The Bath Chronicle, 2 February 1918

[11] This process seems to have been often repeated including restoration work in the mid 1800s (said by Historic Buildings Listing to be 1830-40 and in 1946 when colonnades were installed in the side view to the garden)

[12] The property has several times been occupied by military personnel, in 1881 by Major-General JE Hope and his wife (The Bath Chronicle 30 June 1881).

[13] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 14 June 1919

[14] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 13 May 1926

[15] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 3 July 1926

[16] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 7 January 1933

[17] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 June 1935

[18] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 4 June 1949

[19] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 29 October 1932

[20] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 October 1935

[21] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 17 January 1942

[22] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 8 December 1945

[23] The Bath Chronicle, 11 January 1919

[24] The Bath Chronicle, 15 January 1921

[25] The Bath Chronicle, 20 January 1923 and 21 April 1923

[26] The Bath Chronicle and Herald, 6 July 1935 and 30 November 1935

[27] The Bath Chronicle, 8 September 1923

[28] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 30 April 1932

[29] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 24 July 1937

[30] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 1 December 1945

[31] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 20 September 1947

[32] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 23 August 1947