Victorian Residents of Kingsdown House David Ibberson July 2015

|

Drive or walk up Henley Lane and over Doctors Hill and you arrive outside Kingsdown House. This used to be Box Mad House (later named Kingsdown Lunatic Asylum) which until 1946 served as a private asylum for those afflicted with mental illness. It is said that a Mad House had existed on that site as early as 1615.[1] This article takes up the story of the later history of the asylum after 1800 until the establishment run by Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan, and the closure of the establishment in 1946 when the owner Gerald MacBryan died. All Photos courtesy David Ibberson |

In 1819 there was a report by a philanthropist, Edward Wakefield, into the Box Asylum who described it as: I never recollect to have seen living persons in so wretched a place. He goes on to describe two nearly naked women living on a straw carpet in the cellar and four fully naken women held in a completely dark room. This was a time when attitudes were beginning to change and the management of madness was no longer a matter of confinement of the mentally ill away from the general public.

This was a time when the industry could be highly profitable generating income from private patients and parish rates. There were estimated to be only about 40 institutions licensed under a 1774 Act.[2] The establishment in Box was owned by Charles Cunningham Langworthy MD who lived at Prospect House a quarter of a mile away. Who was this man, Dr Langworthy?

This was a time when the industry could be highly profitable generating income from private patients and parish rates. There were estimated to be only about 40 institutions licensed under a 1774 Act.[2] The establishment in Box was owned by Charles Cunningham Langworthy MD who lived at Prospect House a quarter of a mile away. Who was this man, Dr Langworthy?

Perkinean Electricity and Dr Langworthy

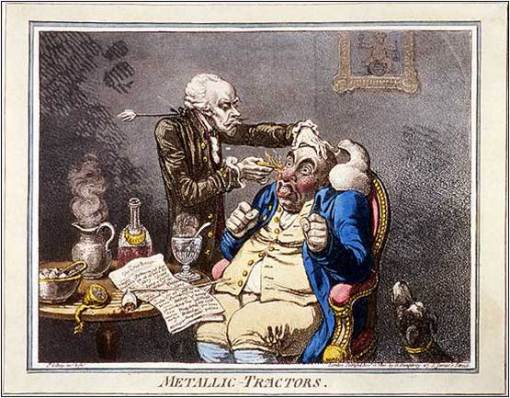

Dr Langworthy was a Bristol surgeon, who moved to Bath to set up what he described as a metallic practice. Here there were rich pickings to be made from the wealthy people who flocked to Bath to take the waters, so Kingsdown House was perhaps something of a sideline. Dr Langworthy became the sales agent for an American, Benjamin Perkins, the son of the inventor of Perkinean Electricity otherwise known as a Mechanical Tractor. Confused? Well don’t be. This device was an instrument that Perkins maintained could ease the pain of many common inflammatory conditions such as gout. How did it work? Well it didn’t, other than in the mind. Dr John Haygarth FRS, another Bath resident, later proved the placebo effect of the Metalic Tractors.

Dr Langworthy was a Bristol surgeon, who moved to Bath to set up what he described as a metallic practice. Here there were rich pickings to be made from the wealthy people who flocked to Bath to take the waters, so Kingsdown House was perhaps something of a sideline. Dr Langworthy became the sales agent for an American, Benjamin Perkins, the son of the inventor of Perkinean Electricity otherwise known as a Mechanical Tractor. Confused? Well don’t be. This device was an instrument that Perkins maintained could ease the pain of many common inflammatory conditions such as gout. How did it work? Well it didn’t, other than in the mind. Dr John Haygarth FRS, another Bath resident, later proved the placebo effect of the Metalic Tractors.

|

It was comprised of two metallic rods (hence metallic practice), about 3 inches long of dis-similar metals which sold for £5 a pair (a year’s pay for a servant). Langworthy was clearly enthused by this instrument and wrote a book published in 1798, A view of the Perkinean Electricity, or, An enquiry into the Influence of Metallic Tractors, founded on a newly discovered principle in nature, and employed as a remedy in many painful inflammatory disorders.

If you have a burning desire to read it, which I doubt, the book can still be purchased on line today. As you would expect, at first the device was hugely popular. However, Perkins was finally discredited and proved to be a fraudster. Right: Illustration courtesy Brian Altonen, Medical Electricity |

To what extent Dr Langworthy was affected by the demise of his tractors? We do not know; nor do we know to what extent he involved it in the activities at Kingsdown House. He continued to live in Bath until his death in 1847 and is buried with his wife, Maria, in the precincts of Bath Abbey.

Severely Censured

An inspection by Commissioners in 1844 sheds some light on the conditions at Kingsdown House. At this time there were about 130 patients, mainly paupers, who paid between 7 and 9 shillings per week (as paupers they had no income so this would be paid for by several parishes merged into a local Poor Law Union).[2] The age profile of those confined suggest that many would be suffering from dementia, but there was still a large number under 40 years of age, some of whom would be suffering from conditions more easily treatable today, for example epilepsy.

The Commission’s report was highly critical, finding strait waistcoats, iron frames, hand-locks, leg-locks and chains being readily used. Staff used excessive force and patients roar (with) excitement. This clearly was not a pleasant place nor one likely to be of benefit to patients. But we should not depict Kingsdown Asylum as being just an institution of physical restraint, and conditions altered dramatically when Dr Robert Langworthy, son of Charles Cunningham, took control. The concern of the Victorians for social improvement meant that conditions were gradually becoming more caring, probably speeded up by the negative Commission Report.

We know that Charles Cunningham Langworthy died in July 1847 and, before then, his son, Dr Robert Austin Langworthy, had taken over the running of Kingsdown Asylum. Dr Robert Langworthy was recognised as an expert in the subject of mental illness.[3]

Physician Heal Thyself

But by this time things were not looking too good for Dr Robert Langworthy. In a report about a purpose-built New County Asylum for Somersetshire in 1842, Dr Robert described how he had taken most of his contracts with the unions and had enlarged his premises accordingly that now the patients should be taken from him.[4] It was to no avail and the provision of County Asylums became compulsory in 1845, when the number of madhouses in England reached 145.

Things got worse because on 23 March 1847 he was admitted as a patient to Fishponds Lunatic Asylum. Sometimes people were reported to the authorities for sexual misbehaviour, stealing or often the removal of a drunken, violent husband (drunkenness was considered a form of mental illness).[5] The following year when he was being considered for discharge, his wife Elizabeth opposed it, and the Commissioners of Lunacy commented that she seemed eager to keep him confined. He was considered well enough to leave Fishponds and return to the management of Kingsdown Asylum, where he was actively trying to restore the credibility of the business.

In 1848 a Novel Cricket Match was held in Box. The report of the event read:

Many of those who take an interest in the improved system of treating the insane were much gratified by witnessing a game of cricket which was played last Thursday in a field near the Lunatic Asylum, Box, by 22 of Dr Langworthy's patients. The appearances of the players was most satisfactory: a spectator could hardly have thought them more mad than the villagers. In the evening Dr Langworthy entertained the players at the Queen's Head Inn, Box.[6]

The same desire to show the best of the asylum was evident from an article in 1849 describing Kingsdown as An Asylum for Lunatics, for the Care of the Incurable and Recovery of Curable Patients; Resident Physician Dr Langworthy.[7] The report went on, This Establishment has been appropriated to its present purposes for more than Two Hundred Years. Patients may adopt any style of living their friends approve of. Amusements, Exercise and Employment will be of a varied character and suited to each individual case.

He died in the spring of 1850 and a year later Elizabeth was recorded as the Proprietor of Kingsdown Lunatic Asylum and living there with her three children, the youngest just 12 years old. Clearly these were difficult times and we get a tantalising glimpse of the problems in running an asylum when a legal action Fuller v Morgan resulted in the house being put up for sale in 1858.[8] It was advertised as: Freehold Estate: Kingsdown House or the Kingsdown Lunatic Asylum.

Severely Censured

An inspection by Commissioners in 1844 sheds some light on the conditions at Kingsdown House. At this time there were about 130 patients, mainly paupers, who paid between 7 and 9 shillings per week (as paupers they had no income so this would be paid for by several parishes merged into a local Poor Law Union).[2] The age profile of those confined suggest that many would be suffering from dementia, but there was still a large number under 40 years of age, some of whom would be suffering from conditions more easily treatable today, for example epilepsy.

The Commission’s report was highly critical, finding strait waistcoats, iron frames, hand-locks, leg-locks and chains being readily used. Staff used excessive force and patients roar (with) excitement. This clearly was not a pleasant place nor one likely to be of benefit to patients. But we should not depict Kingsdown Asylum as being just an institution of physical restraint, and conditions altered dramatically when Dr Robert Langworthy, son of Charles Cunningham, took control. The concern of the Victorians for social improvement meant that conditions were gradually becoming more caring, probably speeded up by the negative Commission Report.

We know that Charles Cunningham Langworthy died in July 1847 and, before then, his son, Dr Robert Austin Langworthy, had taken over the running of Kingsdown Asylum. Dr Robert Langworthy was recognised as an expert in the subject of mental illness.[3]

Physician Heal Thyself

But by this time things were not looking too good for Dr Robert Langworthy. In a report about a purpose-built New County Asylum for Somersetshire in 1842, Dr Robert described how he had taken most of his contracts with the unions and had enlarged his premises accordingly that now the patients should be taken from him.[4] It was to no avail and the provision of County Asylums became compulsory in 1845, when the number of madhouses in England reached 145.

Things got worse because on 23 March 1847 he was admitted as a patient to Fishponds Lunatic Asylum. Sometimes people were reported to the authorities for sexual misbehaviour, stealing or often the removal of a drunken, violent husband (drunkenness was considered a form of mental illness).[5] The following year when he was being considered for discharge, his wife Elizabeth opposed it, and the Commissioners of Lunacy commented that she seemed eager to keep him confined. He was considered well enough to leave Fishponds and return to the management of Kingsdown Asylum, where he was actively trying to restore the credibility of the business.

In 1848 a Novel Cricket Match was held in Box. The report of the event read:

Many of those who take an interest in the improved system of treating the insane were much gratified by witnessing a game of cricket which was played last Thursday in a field near the Lunatic Asylum, Box, by 22 of Dr Langworthy's patients. The appearances of the players was most satisfactory: a spectator could hardly have thought them more mad than the villagers. In the evening Dr Langworthy entertained the players at the Queen's Head Inn, Box.[6]

The same desire to show the best of the asylum was evident from an article in 1849 describing Kingsdown as An Asylum for Lunatics, for the Care of the Incurable and Recovery of Curable Patients; Resident Physician Dr Langworthy.[7] The report went on, This Establishment has been appropriated to its present purposes for more than Two Hundred Years. Patients may adopt any style of living their friends approve of. Amusements, Exercise and Employment will be of a varied character and suited to each individual case.

He died in the spring of 1850 and a year later Elizabeth was recorded as the Proprietor of Kingsdown Lunatic Asylum and living there with her three children, the youngest just 12 years old. Clearly these were difficult times and we get a tantalising glimpse of the problems in running an asylum when a legal action Fuller v Morgan resulted in the house being put up for sale in 1858.[8] It was advertised as: Freehold Estate: Kingsdown House or the Kingsdown Lunatic Asylum.

New Beginnings

The Victorians were increasingly compassionate in the provision of care for the mentally ill. Following an Act of Parliament in 1845, huge county asylums were built to accommodate pauper lunatics (Devizes is one example). These buildings often look austere but recognised the need to give patients hope and provided work on farms and workshops, enabling some to return to their families and lead fulfilling lives. These large institutions signalled the end of some private institutions as poor relief inmates were now treated in the big county asylums.

In 1851 Kingsdown had a staff of thirteen, among them a young resident physician, Dr Joseph Nash, who became the proprietor of the business probably after it was put up for sale in 1858. It was a period of increased care and professional medical assistance. By taking private patients rather than poor relief nominees, Joseph Nash was able to make the business extrememly profitable. By 1871 he had moved with his family to Brockley Hall in Somerset, but he retained ownership of the Lunatic Asylum, probably using an associate practitioner as the resident doctor. In 1878 the license for the Asylum was given in the joint names of Dr Joseph Nash and Dr James Gardener.[9]

Dr Nash retained ownership until his death in 1880 when it passed to his wife. This caused registration problems and his wife was obliged to put an advertisement into the newspaper: Mrs Nash begs to state that the Kingsdown Asylum will be still carried on after the present four month's License, granted for temporary purposes on technical grounds, expires.[10]

The Victorians were increasingly compassionate in the provision of care for the mentally ill. Following an Act of Parliament in 1845, huge county asylums were built to accommodate pauper lunatics (Devizes is one example). These buildings often look austere but recognised the need to give patients hope and provided work on farms and workshops, enabling some to return to their families and lead fulfilling lives. These large institutions signalled the end of some private institutions as poor relief inmates were now treated in the big county asylums.

In 1851 Kingsdown had a staff of thirteen, among them a young resident physician, Dr Joseph Nash, who became the proprietor of the business probably after it was put up for sale in 1858. It was a period of increased care and professional medical assistance. By taking private patients rather than poor relief nominees, Joseph Nash was able to make the business extrememly profitable. By 1871 he had moved with his family to Brockley Hall in Somerset, but he retained ownership of the Lunatic Asylum, probably using an associate practitioner as the resident doctor. In 1878 the license for the Asylum was given in the joint names of Dr Joseph Nash and Dr James Gardener.[9]

Dr Nash retained ownership until his death in 1880 when it passed to his wife. This caused registration problems and his wife was obliged to put an advertisement into the newspaper: Mrs Nash begs to state that the Kingsdown Asylum will be still carried on after the present four month's License, granted for temporary purposes on technical grounds, expires.[10]

Patients in Kingsdown Asylum

The 1841 Census records 133 patients and 13 staff living in Kingsdown Asylum. Among the thirteen staff was the superintendent, Christopher Rigby Tangent (65 years); a housekeeper, Ann Farrent (70 years); and an attendant, Nancy Farrent (40 years), who must have been the housekeeper's daughter. The remainder of the staff were recorded as servants. The majority of the patients were recorded as paupers; only 33 were private.

Records exist in the National Archives of the more eminent patients. One example is Sir James Wilson, 63 years, or to use his full title, Major General Sir James Wilson, a patient at Kingsdown in 1841. Before confinement, Sir James lived at Burnett, near Bath, with his wife and two adopted children. He was a veteran of the Peninsular Wars (1807-1814). His will suggests he might have served with the 40th (2nd Somerset) Regiment of Foot. His will mentions bequests to endow a poor school in Burnett and to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Sir James died in 1847.

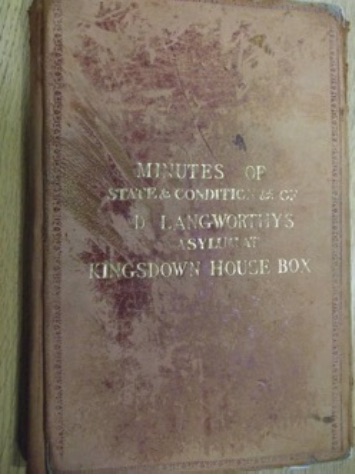

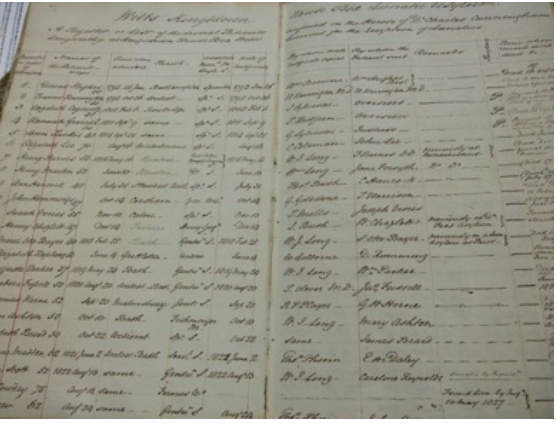

Contrast this with Virtue Tipper, a woman aged 63 years, a pauper from Stowey in the Chew Valley. Virtue was classified as a Lunatic, as distinct from an Idiot. The former is a condition brought on in later life; the latter, present from birth. Kingsdown Asylum was paid seven shillings to pay for her care. We know little about Virtue’s life other than she had spent twenty years in asylums and no doubt died at Kingsdown. I have not been able to identify any documents recording the day-to-day life of those confined in Kingsdown House. However, a leather bound Minutes Book and Register commencing 1825 is held at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre, Chippenham from which can be gleaned some basic facts.

The 1841 Census records 133 patients and 13 staff living in Kingsdown Asylum. Among the thirteen staff was the superintendent, Christopher Rigby Tangent (65 years); a housekeeper, Ann Farrent (70 years); and an attendant, Nancy Farrent (40 years), who must have been the housekeeper's daughter. The remainder of the staff were recorded as servants. The majority of the patients were recorded as paupers; only 33 were private.

Records exist in the National Archives of the more eminent patients. One example is Sir James Wilson, 63 years, or to use his full title, Major General Sir James Wilson, a patient at Kingsdown in 1841. Before confinement, Sir James lived at Burnett, near Bath, with his wife and two adopted children. He was a veteran of the Peninsular Wars (1807-1814). His will suggests he might have served with the 40th (2nd Somerset) Regiment of Foot. His will mentions bequests to endow a poor school in Burnett and to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Sir James died in 1847.

Contrast this with Virtue Tipper, a woman aged 63 years, a pauper from Stowey in the Chew Valley. Virtue was classified as a Lunatic, as distinct from an Idiot. The former is a condition brought on in later life; the latter, present from birth. Kingsdown Asylum was paid seven shillings to pay for her care. We know little about Virtue’s life other than she had spent twenty years in asylums and no doubt died at Kingsdown. I have not been able to identify any documents recording the day-to-day life of those confined in Kingsdown House. However, a leather bound Minutes Book and Register commencing 1825 is held at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre, Chippenham from which can be gleaned some basic facts.

Minutes recording the annual visits of the committee of inspection, one of whom was John Fuller of Neston, are contained within the register. The minutes frequently record that patients were clean and well fed. They also record that the majority of patients were incurable. The chances of patients leaving Kingsdown House were small, unless you were a private patient. One patient, Capt John William Gould of the 63rd Regiment of Foot made his escape on the 21 April 1857 only to be brought back on the 24 April. John died in Kingsdown on 10 November 1862 aged just 33. The cause of death, among other conditions, was epilepsy. A more fortunate patient was Charles Searle Baycliffe, a medical student from Sheffield who, on admission in 1853, was 20 years old. He was discharged as being cured in 1855.

Also in the Wiltshire History Centre are architects' drawings dated about 1880 which seem to show the work necessary to make Kingsdown House suitable for private patients only. These show an almost independent institution with its own brew-house, beer cellar, dairy, bake-house etc. It was strictly segregated with separate male and female activity areas which included sitting rooms and yards. There were hot and cold bathing facilities with separate washrooms and in the yards, water closets. Gone were the large multi-occupation dormitories, characteristic of workhouses, and small single-occupancy bedrooms appear to be the norm. Really, they are not far removed from the care homes we see today, enormous progress in a hundred years.

Also in the Wiltshire History Centre are architects' drawings dated about 1880 which seem to show the work necessary to make Kingsdown House suitable for private patients only. These show an almost independent institution with its own brew-house, beer cellar, dairy, bake-house etc. It was strictly segregated with separate male and female activity areas which included sitting rooms and yards. There were hot and cold bathing facilities with separate washrooms and in the yards, water closets. Gone were the large multi-occupation dormitories, characteristic of workhouses, and small single-occupancy bedrooms appear to be the norm. Really, they are not far removed from the care homes we see today, enormous progress in a hundred years.

Modern Times

Establishments like Kingsdown became dependent on private patients until the National Health Service reorganisation in 1948.

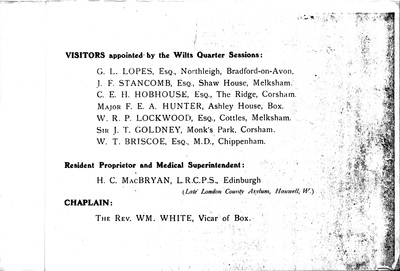

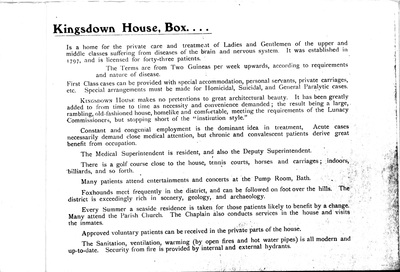

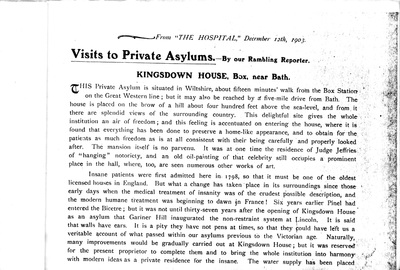

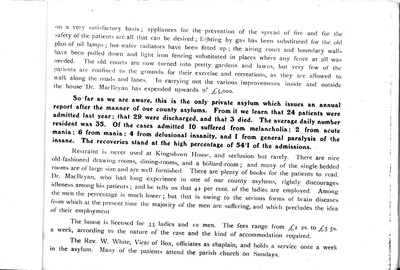

In the early 1900s, Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan was the resident physician at Kingsdown and was in fact described as a psychiatrist, specialising in the treatment of the mental illnesses of his private patients. Dr MacBryan was a partner in the business and lived in Kingsdown House with his six children. One of these, John Crawford William (Jack) MacBryan achieved some sporting distinction by winning a Gold Medal for hockey in the 1920 Olympics, and later became the only England Test Cricketer not to score any runs, bowl any balls or dismiss anyone in a Test Match. He was however, a very successful Somerset County batsman.

Establishments like Kingsdown became dependent on private patients until the National Health Service reorganisation in 1948.

In the early 1900s, Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan was the resident physician at Kingsdown and was in fact described as a psychiatrist, specialising in the treatment of the mental illnesses of his private patients. Dr MacBryan was a partner in the business and lived in Kingsdown House with his six children. One of these, John Crawford William (Jack) MacBryan achieved some sporting distinction by winning a Gold Medal for hockey in the 1920 Olympics, and later became the only England Test Cricketer not to score any runs, bowl any balls or dismiss anyone in a Test Match. He was however, a very successful Somerset County batsman.

Above: the narrative of Dr MacBryan's brochure recorded in The Hospital, 12 December 1903 (Courtesy Wiltshire History Centre)

There is no doubt that Dr MacBryan ran a caring regime where patients were allowed to go on trips accompanied by medical staff. But this also produced problems as evidenced by a newspaper report of 1912:[11]

Terrible Tragedy at Box: Demented Lady Throws herself in Front of Train.

Miss Lucy Geraldine Deykin, aged 36, was going to Bath by train to attend a Pump Room Concert, attended by a nurse Miss Elizabeth Holley, aged 23. Miss Deykin suddenly lept from the platform and lay with her head on the down line facing the train in a kneeling position. Miss Holley tried to drag her away but could not budge her and only missed the express train travelling at 60 miles per hour by half a second. It is impossible to speak too highly of Miss Holley's plucky action. Dr Symes of the Hermitage attended what was left of the body. Dr Phillip Johnson of Kingsdown House was in charge of the asylum at the time, Dr MacBryan being on holiday with his family.

There were several specialist staff, as well as the proprietor, in attendance at the asylum in the years between the two World Wars. Dr Percy Armstrong Dykes of Bristol University and Guy's Hospital, London, was the superintendent of the house for many years after World War One.[12] Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan lived into the mid 1900s. At his funeral in 1943 representatives of Kingsdown House included Dr F Barton White, superintendent, and matron Elizabeth Hinton represented the indoor staff, whilst Mr Tiley and Mr Painter represented the outdoor staff.[13]

Terrible Tragedy at Box: Demented Lady Throws herself in Front of Train.

Miss Lucy Geraldine Deykin, aged 36, was going to Bath by train to attend a Pump Room Concert, attended by a nurse Miss Elizabeth Holley, aged 23. Miss Deykin suddenly lept from the platform and lay with her head on the down line facing the train in a kneeling position. Miss Holley tried to drag her away but could not budge her and only missed the express train travelling at 60 miles per hour by half a second. It is impossible to speak too highly of Miss Holley's plucky action. Dr Symes of the Hermitage attended what was left of the body. Dr Phillip Johnson of Kingsdown House was in charge of the asylum at the time, Dr MacBryan being on holiday with his family.

There were several specialist staff, as well as the proprietor, in attendance at the asylum in the years between the two World Wars. Dr Percy Armstrong Dykes of Bristol University and Guy's Hospital, London, was the superintendent of the house for many years after World War One.[12] Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan lived into the mid 1900s. At his funeral in 1943 representatives of Kingsdown House included Dr F Barton White, superintendent, and matron Elizabeth Hinton represented the indoor staff, whilst Mr Tiley and Mr Painter represented the outdoor staff.[13]

On Dr MacBryan's death his younger son, Mr Gerald MacBryan, inherited Kingsdown House. Gerald was, to say the least, an unusual person. In the 1930s he courted the daughter of his employer, the Rajah of Sarawak, but failed. He converted to Islam and married a Muslim woman. With the outbreak of the Second World War he returned to Sarawak, leaving the establishment in the hands of his staff, particularly matron Elizabeth Hinton. He died in Hong Kong in November 1946, described by a member of staff as a down and out in filthy rags trying to direct the street traffic, although he had thousands of dollars in the bank.[14] By then it had been decided to close the institution.[15]

Conclusion

In judging the work of Kingsdown Asylum, we must remember that, even in this enlightened society, large institutions designed to treat the mentally ill still existed until recently and that patients were subjected to barbaric treatments like electric shock therapy. The story of Kingsdown Asylum is not a happy one, either for the patients or the owners. Even today, mental illness is a problem that we fail to understand and society fails to treat adequately.

In judging the work of Kingsdown Asylum, we must remember that, even in this enlightened society, large institutions designed to treat the mentally ill still existed until recently and that patients were subjected to barbaric treatments like electric shock therapy. The story of Kingsdown Asylum is not a happy one, either for the patients or the owners. Even today, mental illness is a problem that we fail to understand and society fails to treat adequately.

Sources

Index of Lunatic Asylums and Mental Hospitals –www.studymore.org.uk

Kingsdown House Lunatic Asylum, Wiltshire OPC

CC Booth, John Haygarth (1740-1826) A Physician of the Enlightenment

www.ancestry.co.uk 1841 and 1851 Census, the Will of Sir James Wilson

W Ll Parry-Jones, The Trade in Lunacy, 1972

http://gbolympics.co.uk/hockey.html John William Crawford MacBryan

W. Leighton, The Manor and Parish of Burnett Somerset,1937, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucester Archaeological Society, Vol 59 pages 243-285

National Archives, Sir James Wilson, Virtue Tipper and Dr Robert Langworthy, Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre Cat Ref A1/560/1 and A1/562/5L

Index of Lunatic Asylums and Mental Hospitals –www.studymore.org.uk

Kingsdown House Lunatic Asylum, Wiltshire OPC

CC Booth, John Haygarth (1740-1826) A Physician of the Enlightenment

www.ancestry.co.uk 1841 and 1851 Census, the Will of Sir James Wilson

W Ll Parry-Jones, The Trade in Lunacy, 1972

http://gbolympics.co.uk/hockey.html John William Crawford MacBryan

W. Leighton, The Manor and Parish of Burnett Somerset,1937, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucester Archaeological Society, Vol 59 pages 243-285

National Archives, Sir James Wilson, Virtue Tipper and Dr Robert Langworthy, Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre Cat Ref A1/560/1 and A1/562/5L

|

Owners of Kingsdown Asylum

Date 1749 - 1763 Pre - 1819 Pre - 1844 - 1850 1850 - possibly 1858 Possibly 1858 - 1880 1880 - unknown unknown - 1943 1943 - 1946 1946 - on |

Name James Jeffery Charles Cunningham Langworthy, succeeded by his son Robert Austin Langworthy, succeeded by his wife Elizabeth Langworthy Joseph Nash, succeeded by his wife Elizabeth Anne Nash (nee Holworthy) Henry Crawford MacBryan, succeeded by his son Gerald MacBryan Closed and converted into private residences |

References

[1] Wiliam Parry-Jones,The Trade in Lunacy, 1972, Routledge & Kegan Paul plc, stated that it was the oldest licensed house dated 1615. The Parish Magazine of November 1946 reported that it was originally a convent and converted in 1630 into a house for the reception of persons suffering from mental and nervous disorders.

[2] WLl Parry-Jones, English Private Madhouses in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, 1972, Proc.roy.Soc.Med.Volume 66 July 1973, p.660

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 26 February 1846

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 24 March 1842

[5] Sarah Wise, Inconvenient People: Tales From Victorian Lunacy Panics, National Archives Podcast, 26 June 2014

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 11 October 1849

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 11 January 1849

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 14 October 1858

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 11 July 1878

[10] The Bath Chronicle, 15 July 1880

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 23 November 1912, subsequently amended by 30 November 1912

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 28 October 1939

[13] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 May 1943

[14] Parish Magazine

[15] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 8 May 1943 and Parish Magazine, November 1946

[1] Wiliam Parry-Jones,The Trade in Lunacy, 1972, Routledge & Kegan Paul plc, stated that it was the oldest licensed house dated 1615. The Parish Magazine of November 1946 reported that it was originally a convent and converted in 1630 into a house for the reception of persons suffering from mental and nervous disorders.

[2] WLl Parry-Jones, English Private Madhouses in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, 1972, Proc.roy.Soc.Med.Volume 66 July 1973, p.660

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 26 February 1846

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 24 March 1842

[5] Sarah Wise, Inconvenient People: Tales From Victorian Lunacy Panics, National Archives Podcast, 26 June 2014

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 11 October 1849

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 11 January 1849

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 14 October 1858

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 11 July 1878

[10] The Bath Chronicle, 15 July 1880

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 23 November 1912, subsequently amended by 30 November 1912

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 28 October 1939

[13] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 May 1943

[14] Parish Magazine

[15] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 8 May 1943 and Parish Magazine, November 1946