|

Monuments in St Thomas à Becket Churchyard Charles Freeman Photos courtesy Carol Payne, unless stated otherwise June 2019 There are a staggering 65 monuments identified with Grade II listing in the churchyard of St Thomas à Becket. Most were listed in 1960 and an attempt made to identify them in 2002. They show us a lot about Georgian society in the village because 52 have been dated to the Georgian period, comprising 13 identified as mid-Georgian period, 16 mid to late(r), 23 late(r). Before the era of headstones each plot was probably used repeatedly. Considering that hundreds of people were buried there over very many centuries, it is significant that 80% of the monuments date from that period and the remaining ones from the early Victorian period. The Order in Council to close the churchyard was approved by Queen Victoria at Windsor on 6 April 1858. Right: View of part of Box Churchyard from the parapet of the tower |

Churchyard Architecture

The churchyard monuments reflect a sculptural trend towards Classicism in certain sectors of Box society and the names on the family tombs reflect the village gentry, who could demonstrate their status through their wealth in death. The monuments also show the extent of the stone industry and masons work in Box.

Compared to the High Victorian period missing are the ornate carvings of flowers and plants, representing rebirth, and winged angels, depicting the ascent to heaven. Certainly, there are no cherubs to be seen in the churchyard. This would have been considered vulgar in the Georgian period. The simplicity of the carvings is in contrast to the ornateness of several interior epitaphs in Box Church, where the wealthier families were honoured.

The churchyard monuments reflect a sculptural trend towards Classicism in certain sectors of Box society and the names on the family tombs reflect the village gentry, who could demonstrate their status through their wealth in death. The monuments also show the extent of the stone industry and masons work in Box.

Compared to the High Victorian period missing are the ornate carvings of flowers and plants, representing rebirth, and winged angels, depicting the ascent to heaven. Certainly, there are no cherubs to be seen in the churchyard. This would have been considered vulgar in the Georgian period. The simplicity of the carvings is in contrast to the ornateness of several interior epitaphs in Box Church, where the wealthier families were honoured.

People Buried in Box Churchyard

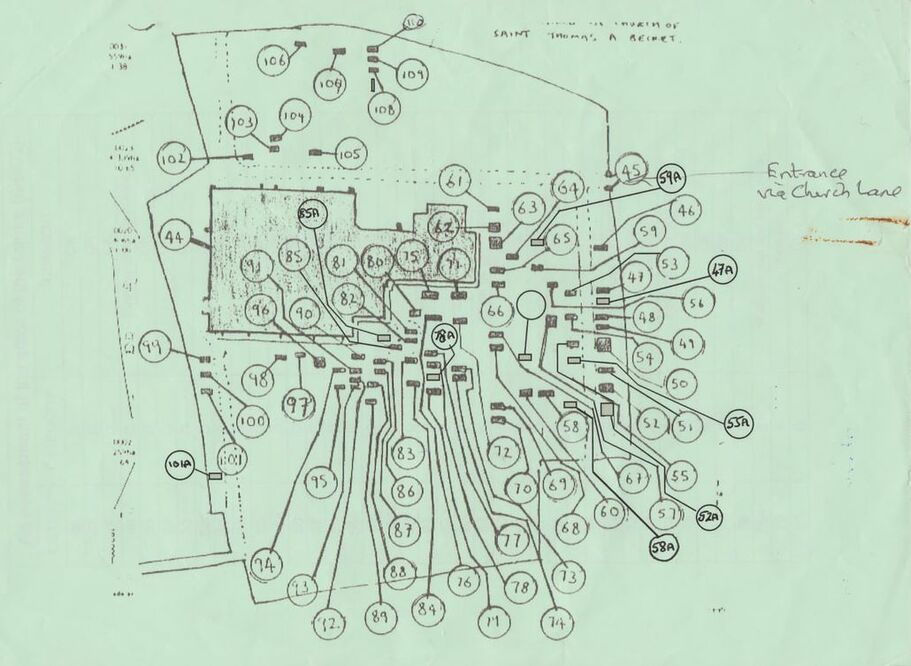

The absence of religiosity in the monuments is quite striking. Instead the preference was for headstones and chest monuments to record family names including distant relatives. You can identify the precise plots from the Historic Buildings listing, using the map and drop-down listing below. Most names are of the aspiring classes - yeoman farmers such as WJ Brown (3/107), wealthy craftsmen such as the Bullock family of clockmakers (3/53), the Mullins family who were parish clerks and schoolteachers (3/65), and the wealthy Neat family of Middlehill (3/66).

The absence of religiosity in the monuments is quite striking. Instead the preference was for headstones and chest monuments to record family names including distant relatives. You can identify the precise plots from the Historic Buildings listing, using the map and drop-down listing below. Most names are of the aspiring classes - yeoman farmers such as WJ Brown (3/107), wealthy craftsmen such as the Bullock family of clockmakers (3/53), the Mullins family who were parish clerks and schoolteachers (3/65), and the wealthy Neat family of Middlehill (3/66).

|

The Mullins family tombs are a good illustration of the Georgian interest in recording and honouring ancestors. It was partly a way of establishing your family credentials in the hope that you might one day be part of the gentry class. In two large Mullins tombs were:[1]

Thomas Nutt (for whose family this tomb was originally opened), died 23 February 1748, aged 61, and Ann, his wife, died 15 October 1745, aged 52, together with their son, John, died 5 March 1737, aged 8; their daughter Mary, died 28 July 1801, aged 73, and her husband George Mullins, died 7 August 1796, aged 67. Also, a number of children of George and Mary – their son John, died 30 June 1807, aged 44, and his wife Susannah, died 9 April 1853, aged 76; their son Edward, died 31 July 1813, aged 50, and Rachel his wife, died 18 February 1847, aged 74; and five further children who died as infants. |

George Mullins, died 9 December 1733, aged 66, and Elizabeth his (second) wife, died 8 February 1766, aged 90. Their daughter Susannah, died 8 May 1778, aged 69 with her husband James Phillips, died 3 August 1786, aged 80. Edward Mullins, died 19 April 1746, aged 43, and Lydia his wife, died 8 May 1746, aged 42. Jane Mullins, daughter of George and Mary (Nutt), died 19 March 1816, aged 65. George Mullins, died 16 February 1842, age (nor given on grave but was 82) and Mary his wife, died 5 November 1844, aged 85.

|

Types of Monuments in Box Graveyard

The marking of graves is, of course, prehistoric and styles of marker stones vary over the ages from the date of the great Neolithic long barrow funeral chambers, so common in Wiltshire. The monuments which remain in Box churchyard today do so only by chance, by the mixture of the quality of materials used, and by the absence of over-burial. The Georgian period was a period of enclosed chest-tombs, a chamber area where whole families could be held together in perpetuity. Box Churchyard reflects the wealth of certain families and their perceived right to permanent memory in the village. Some believe that the custom of churchyard burial only became the norm after about 1650 but there is virtually no evidence of the burial of working-class people in the churchyard. There are only a few unusual monuments which include the pyramid stone (right) over the grave of a woman, who reportedly wanted to stop her husband dancing on her grave.[2] |

Historic Buildings Listing of Box Monuments

You can read the description of the monuments produced in 1960 in the drop-down list below. The reference numbers on the map and in this article relate to the listed buildings identification.

You can read the description of the monuments produced in 1960 in the drop-down list below. The reference numbers on the map and in this article relate to the listed buildings identification.

| box_churchyard_listed_buildings.pdf | |

| File Size: | 2392 kb |

| File Type: | |

Closure of Box Churchyard

The number of monuments is indicative of the increasing wealth of Box residents and the popularity of Box churchyard. To cope with this, in 1846 the churchyard was expanded to the south up the slope to the line of the present (partly collapsed) wall. Two strips of land were purchased from the Horlock family that year. Rev Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock was the Vicar but the land seems to have been owned by his family separately from any church connection.

The decision to stop burials in Box Churchyard in 1858 was triggered by disease and death at next door Box House due to contamination of the water supply, although there were local rumours of malfeasance by Rev Horlock because of the death of his wife and sister-in-law, both from the Sudell family. A small number of burials, perhaps four or five, took place subsequently under the clause which allowed this in vaults and walled graves existing on eleventh January, one thousand eight hundred and fifty-eight, in which each coffin shall be entombed in charcoal, and separately entombed in an air-tight manner.

Conclusion

The graves in Box Churchyard have lost much of their original purpose. Before the Reformation, people were buried in this consecrated ground under the close supervision of the priest so that their bodies could be reunited with their immortal souls at the Day of Judgement. By the Georgian period, the tombs were a way of honouring the history of families of a certain status in society. The lettering on the tombs continue to deteriorate and there seems little can be done about this.

The Local Government Act of 1972 allowed responsibility for maintenance of closed churchyards to be transferred to Local Authorities. Box Parochial Church Council decided to take this step in 2014. Responsibility was transferred to Box Parish Council which then passed it to Wiltshire Council, in accordance with normal allocation of local government responsibilities. Ownership of the churchyard remains with the Incumbent, not the local authority, and any work or alteration in the churchyard still falls under ecclesiastical law and therefore requires a Faculty, the church's equivalent of Planning Permission. Responsibility for individual memorials actually lies with the family of the deceased but nowadays, when very few families stay in the village for countless generations, it is seldom possible to trace the descendants, and even rarer for them to want to spend money on the care of their forefathers' graves. One parishioner, John Neat, in 1844 left an investment from which the interest was to be used (and is used) for the care of the family tomb. Not surprisingly it is in better condition than most others in the churchyard. Another trust fund, Hobbs and Holworthy, in the care of the church produces interest for the care of one other tomb, but that is in the civil cemetery on the A4.

The weight of the stones is causing some subsidence. The cages which have been erected on Health and Safety grounds around some of the tombs were placed there in 2015 by Wiltshire Council as a temporary measure. The PCC, with full support from the diocese, is strongly challenging the need for these and pressing hard for a proper long-term solution. As well as looking after the site and the historic monuments, we have a responsibility to honour the story of these individuals and to record their epitaphs where possible. We are grateful to the vicar of Box Church, the churchwardens and the Box Parochial Church Council for doing all they can to safeguard this history.

The number of monuments is indicative of the increasing wealth of Box residents and the popularity of Box churchyard. To cope with this, in 1846 the churchyard was expanded to the south up the slope to the line of the present (partly collapsed) wall. Two strips of land were purchased from the Horlock family that year. Rev Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock was the Vicar but the land seems to have been owned by his family separately from any church connection.

The decision to stop burials in Box Churchyard in 1858 was triggered by disease and death at next door Box House due to contamination of the water supply, although there were local rumours of malfeasance by Rev Horlock because of the death of his wife and sister-in-law, both from the Sudell family. A small number of burials, perhaps four or five, took place subsequently under the clause which allowed this in vaults and walled graves existing on eleventh January, one thousand eight hundred and fifty-eight, in which each coffin shall be entombed in charcoal, and separately entombed in an air-tight manner.

Conclusion

The graves in Box Churchyard have lost much of their original purpose. Before the Reformation, people were buried in this consecrated ground under the close supervision of the priest so that their bodies could be reunited with their immortal souls at the Day of Judgement. By the Georgian period, the tombs were a way of honouring the history of families of a certain status in society. The lettering on the tombs continue to deteriorate and there seems little can be done about this.

The Local Government Act of 1972 allowed responsibility for maintenance of closed churchyards to be transferred to Local Authorities. Box Parochial Church Council decided to take this step in 2014. Responsibility was transferred to Box Parish Council which then passed it to Wiltshire Council, in accordance with normal allocation of local government responsibilities. Ownership of the churchyard remains with the Incumbent, not the local authority, and any work or alteration in the churchyard still falls under ecclesiastical law and therefore requires a Faculty, the church's equivalent of Planning Permission. Responsibility for individual memorials actually lies with the family of the deceased but nowadays, when very few families stay in the village for countless generations, it is seldom possible to trace the descendants, and even rarer for them to want to spend money on the care of their forefathers' graves. One parishioner, John Neat, in 1844 left an investment from which the interest was to be used (and is used) for the care of the family tomb. Not surprisingly it is in better condition than most others in the churchyard. Another trust fund, Hobbs and Holworthy, in the care of the church produces interest for the care of one other tomb, but that is in the civil cemetery on the A4.

The weight of the stones is causing some subsidence. The cages which have been erected on Health and Safety grounds around some of the tombs were placed there in 2015 by Wiltshire Council as a temporary measure. The PCC, with full support from the diocese, is strongly challenging the need for these and pressing hard for a proper long-term solution. As well as looking after the site and the historic monuments, we have a responsibility to honour the story of these individuals and to record their epitaphs where possible. We are grateful to the vicar of Box Church, the churchwardens and the Box Parochial Church Council for doing all they can to safeguard this history.

References

[1] Patrick Mullins, The Mullins Family of Box, Wiltshire, 1991, p.25

[2] David Ibberson, The Box Collection, about 1987, private publication, p.44

[1] Patrick Mullins, The Mullins Family of Box, Wiltshire, 1991, p.25

[2] David Ibberson, The Box Collection, about 1987, private publication, p.44