Selling Up Alan Payne November 2020

Many people chart the history of their house from the time that their plot was bought from the estate of the Northey family by a private individual. There were three major auctions of Northey property: the Ashley estate in 1912, part of the Box estate in 1919 and more of Box in 1923. These received much publicity, partly because they came as a surprise to contemporaries, but these were just the highly-promoted sales and there were many other disposals.

Economic Background

It has been said that the estate of the Rev Edward William Northey (George Wilbraham’s brother) declined from 1,307 acres in Box by about half between 1873 and 1894.[1] They still held much land and the period after 1880 has been called an Indian Summer for the English landed gentry.[2] It was a time of the flowering of this social class before their almost total decline by the end of the Second World War. There were many factors causing the decline, from societal reasons with the rise of Victorian middle-class culture, to the collapse of the agricultural economy struggling to compete with cheap, free trade, imported foodstuffs from the Empire.[3] There were also significant democratic changes introduced by the Local Government Act of 1894 which established Box Parish Council and the 1882 Settled Land Act which allowed farming tenants to sell their interest in property.[4]

The Northey family were not alone in struggling with these issues. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s many owners of landed estates tried to sell up, especially those faced with large personal debt. There had been a considerable decline in agricultural rental income which was exacerbated by the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 which abolished minimum prices for British corn and encouraged a flood of cheap imported agricultural produce after 1873. Government policy also affected landlords’ incomes. The 1909 Budget introduced an Undeveloped Land Tax and an Incremental Value Duty on land (later increased by basing on current values rather than rental multiples). These encouraged a flood of estate sales including Walter Long's sales of his Wiltshire Estates in 1910. The Marquess of Bath sold 8,600 acres of his Longleat Estate between 1919 and 1921.[5]

The Northeys had considerable protection from these problems through the will trusts which determined the order of succession whenever inheritance issues arose. But the trusts also brought problems in balancing estate values between Box and Epsom. These came to the fore when George Wilbraham wanted more of a breach from the Epsom estate after 1880. In return for relinquishing assets, Rev Edward William Northey took out a mortgage of £4,000 (roughly equivalent to half a million pounds today) on the trust land lying to the East of Box Brook (also known as River Weaving) at interest of 4% on 26 June 1884.[6] The land appears to be the 12 acres on the south side of the A4 road from Bulls Lane up to the railway bridge, then tenanted by James Vezey. In order to understand the impact of these economic and social factors, we need to go back to the very start of the Northey ownership of Box and Ashley.

Early Property Sales

Early land disposals seem to be organisational, one-off sales and probably the part of a constant arranging and rearranging of the estate land for commercial reasons. We see this clearly in their attitude to mill ownership. In 1729 Thomas Nutt bought The Wilderness from William Northey, disposing of the old Beckett Mill on the site.[7] The mill was not needed in the estate because the family also owned Box Mill, Cuttings Mill and Drewetts Mill. Circumstances in the village changed significantly with the building of the 1761 road from Corsham to Box (the A4) and the sale in the 1770s of Drewetts Mill to Edward Lee, the miller at the time probably reflects the desire of the family to concentrate trade in their Box Mill. The coming of the railways in the late 1830s occasioned the disposal of parcels of land around the east of the village but this was a rather opportunistic development. Cuttings Mill had already fallen into disuse and the sale suited everyone.

This discovery of extensive building stone appears to have started a shift in the Northey’s business plan. It was followed by the sale of rights to extract minerals in quarry areas, not the alienation of the land itself. In 1839 a right of way was granted over land called Barn Piece, originally a quarry site. It was followed by the lease of mineral extraction rights to the Great Western Railway in the same year.[8] The granting of extraction rights had unforeseen consequences in the creation of waste areas around the quarries. In 1876. Rev Edward William Northey had to sue for the recovery of the garden in front of Rokeby Villa, which gave an entrance to the Quarry Hill road.

Sales in Central Box

By the late 1880s a deliberate plan had emerged for the development of the Devizes Road by selling individual plots of land. Having resisted this for decades after the road was completed in 1841, the development of the area started with the sale of Charlotte Cottage in 1880 and the expansion of property up the road after 1884 with Woodland View 1893, Rose Bank 1894, Lyndale and Fernlea about 1896, Elmslea 1898, Beulah 1901 and Creffield 1905. The planning for these sales was a decision of the trustees but we must assume that George Wilbraham was a major instigator particularly after he came into control on the death of his father in 1880.

Having encroached on land in the centre of Box, the farmland of Mead Farm was a target for exploitation. The supply of water to the east of the old village opened the area for development starting with the New Schools in 1875, the Poynder Fountain in 1878 and the demolition of the old toll house and the building of the Post Office in 1885.

Ribbon development quickly followed along the line of the A4 road. On the south side of the road new houses emerged: Burton House 1880 and Northfield House 1889.[9] Mead Villas were built in 1906 when Rev Edward Northey of Epsom sold the freehold of Farm Mead to William Bird, the landlord of the Bear. There followed further disposals of plots along the main road: between the Queen’s Head and The Bear pubs, then land to the east of Manor Farm with the High Street after 1899. Lorne House and Glenavon are first mentioned after 1880, Roseland Villa and Myrtle Grove after 1889, Kingston Villas 1901-07 and Villa Rosa in 1915.[10]

It has been said that the estate of the Rev Edward William Northey (George Wilbraham’s brother) declined from 1,307 acres in Box by about half between 1873 and 1894.[1] They still held much land and the period after 1880 has been called an Indian Summer for the English landed gentry.[2] It was a time of the flowering of this social class before their almost total decline by the end of the Second World War. There were many factors causing the decline, from societal reasons with the rise of Victorian middle-class culture, to the collapse of the agricultural economy struggling to compete with cheap, free trade, imported foodstuffs from the Empire.[3] There were also significant democratic changes introduced by the Local Government Act of 1894 which established Box Parish Council and the 1882 Settled Land Act which allowed farming tenants to sell their interest in property.[4]

The Northey family were not alone in struggling with these issues. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s many owners of landed estates tried to sell up, especially those faced with large personal debt. There had been a considerable decline in agricultural rental income which was exacerbated by the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 which abolished minimum prices for British corn and encouraged a flood of cheap imported agricultural produce after 1873. Government policy also affected landlords’ incomes. The 1909 Budget introduced an Undeveloped Land Tax and an Incremental Value Duty on land (later increased by basing on current values rather than rental multiples). These encouraged a flood of estate sales including Walter Long's sales of his Wiltshire Estates in 1910. The Marquess of Bath sold 8,600 acres of his Longleat Estate between 1919 and 1921.[5]

The Northeys had considerable protection from these problems through the will trusts which determined the order of succession whenever inheritance issues arose. But the trusts also brought problems in balancing estate values between Box and Epsom. These came to the fore when George Wilbraham wanted more of a breach from the Epsom estate after 1880. In return for relinquishing assets, Rev Edward William Northey took out a mortgage of £4,000 (roughly equivalent to half a million pounds today) on the trust land lying to the East of Box Brook (also known as River Weaving) at interest of 4% on 26 June 1884.[6] The land appears to be the 12 acres on the south side of the A4 road from Bulls Lane up to the railway bridge, then tenanted by James Vezey. In order to understand the impact of these economic and social factors, we need to go back to the very start of the Northey ownership of Box and Ashley.

Early Property Sales

Early land disposals seem to be organisational, one-off sales and probably the part of a constant arranging and rearranging of the estate land for commercial reasons. We see this clearly in their attitude to mill ownership. In 1729 Thomas Nutt bought The Wilderness from William Northey, disposing of the old Beckett Mill on the site.[7] The mill was not needed in the estate because the family also owned Box Mill, Cuttings Mill and Drewetts Mill. Circumstances in the village changed significantly with the building of the 1761 road from Corsham to Box (the A4) and the sale in the 1770s of Drewetts Mill to Edward Lee, the miller at the time probably reflects the desire of the family to concentrate trade in their Box Mill. The coming of the railways in the late 1830s occasioned the disposal of parcels of land around the east of the village but this was a rather opportunistic development. Cuttings Mill had already fallen into disuse and the sale suited everyone.

This discovery of extensive building stone appears to have started a shift in the Northey’s business plan. It was followed by the sale of rights to extract minerals in quarry areas, not the alienation of the land itself. In 1839 a right of way was granted over land called Barn Piece, originally a quarry site. It was followed by the lease of mineral extraction rights to the Great Western Railway in the same year.[8] The granting of extraction rights had unforeseen consequences in the creation of waste areas around the quarries. In 1876. Rev Edward William Northey had to sue for the recovery of the garden in front of Rokeby Villa, which gave an entrance to the Quarry Hill road.

Sales in Central Box

By the late 1880s a deliberate plan had emerged for the development of the Devizes Road by selling individual plots of land. Having resisted this for decades after the road was completed in 1841, the development of the area started with the sale of Charlotte Cottage in 1880 and the expansion of property up the road after 1884 with Woodland View 1893, Rose Bank 1894, Lyndale and Fernlea about 1896, Elmslea 1898, Beulah 1901 and Creffield 1905. The planning for these sales was a decision of the trustees but we must assume that George Wilbraham was a major instigator particularly after he came into control on the death of his father in 1880.

Having encroached on land in the centre of Box, the farmland of Mead Farm was a target for exploitation. The supply of water to the east of the old village opened the area for development starting with the New Schools in 1875, the Poynder Fountain in 1878 and the demolition of the old toll house and the building of the Post Office in 1885.

Ribbon development quickly followed along the line of the A4 road. On the south side of the road new houses emerged: Burton House 1880 and Northfield House 1889.[9] Mead Villas were built in 1906 when Rev Edward Northey of Epsom sold the freehold of Farm Mead to William Bird, the landlord of the Bear. There followed further disposals of plots along the main road: between the Queen’s Head and The Bear pubs, then land to the east of Manor Farm with the High Street after 1899. Lorne House and Glenavon are first mentioned after 1880, Roseland Villa and Myrtle Grove after 1889, Kingston Villas 1901-07 and Villa Rosa in 1915.[10]

Quarry Assets

After 1880, the family seem to have had a deliberate policy of letting out mineral extraction rights as a way of supplementing their farm tenancy income. In 1886 they made various tenancies: leasing some quarry rights to Randall, Saunders & Co, separate rights at Kingsdown Quarry to Richard Marsh & Co, and then land to Robert Strong.[11] The following year they let Wadswick quarry to Cornelius James Pictor, and another part of Kingsdown to Richard Joseph Marsh & Co, and so it went on for about a decade. It wasn’t easy to guess where the seams of good stone might exist and getting quarrymen to speculate and pay rent was also difficult. In 1881 the family set up their own company, the Box Bath Stone Company Limited but neither the family nor their agent had experience of the industry and the business failed seven years later.[12]

In 1893 they opened The Northey Stone Company Ltd at Longsplatt with four miners and twelve men in the stoneyard. The quarry was accessed down steps in a 45-degree sloping shaft to the quarry face. On the surface was a substantial stoneyard and a horse-gin to pull the stone to the surface. Buildings in the yard included stables for the horses and masonry offices to plan the measurements needed and organise the cutting of the stone.

The whole operation was small-scale and scarcely profitable. In 1896 it was leased to James and William Turner from Cardiff, who called themselves the United Stone Firms Ltd. By 1907 it wasn't producing enough stone, which had to be bought in and it was worked out within 20 years and went into liquidation in 1913.

After 1880, the family seem to have had a deliberate policy of letting out mineral extraction rights as a way of supplementing their farm tenancy income. In 1886 they made various tenancies: leasing some quarry rights to Randall, Saunders & Co, separate rights at Kingsdown Quarry to Richard Marsh & Co, and then land to Robert Strong.[11] The following year they let Wadswick quarry to Cornelius James Pictor, and another part of Kingsdown to Richard Joseph Marsh & Co, and so it went on for about a decade. It wasn’t easy to guess where the seams of good stone might exist and getting quarrymen to speculate and pay rent was also difficult. In 1881 the family set up their own company, the Box Bath Stone Company Limited but neither the family nor their agent had experience of the industry and the business failed seven years later.[12]

In 1893 they opened The Northey Stone Company Ltd at Longsplatt with four miners and twelve men in the stoneyard. The quarry was accessed down steps in a 45-degree sloping shaft to the quarry face. On the surface was a substantial stoneyard and a horse-gin to pull the stone to the surface. Buildings in the yard included stables for the horses and masonry offices to plan the measurements needed and organise the cutting of the stone.

The whole operation was small-scale and scarcely profitable. In 1896 it was leased to James and William Turner from Cardiff, who called themselves the United Stone Firms Ltd. By 1907 it wasn't producing enough stone, which had to be bought in and it was worked out within 20 years and went into liquidation in 1913.

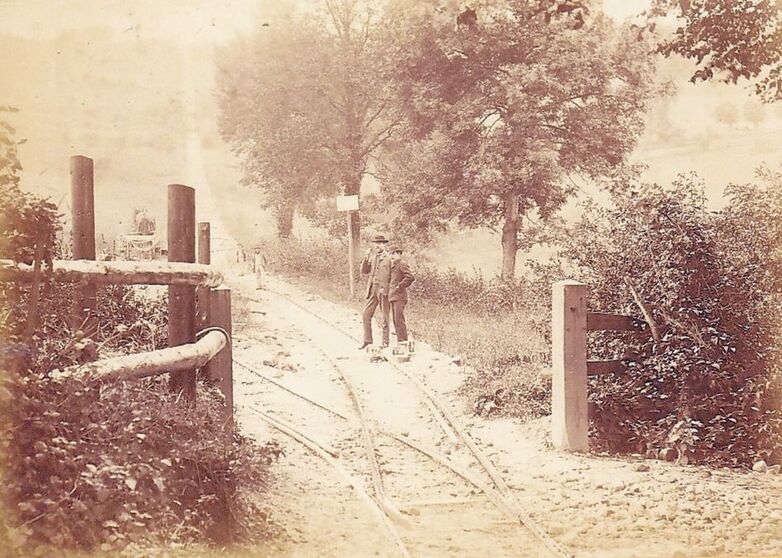

The Northey family sought to develop a direct connection between Monkton Farleigh Quarries and the Box Railway Station by building a rail track on a spectacular embankment passing under Kingsdown Road.[13] The tramway line was called the Farleigh Down Tramway Company and it ran from Monkton Farleigh Quarries through Box and onto GWR from 1881 until the rails were removed in 1935. In 1881, George Wilbraham Northey, Esq, of Cavendish Place, Bath (in other words before he moved into Hazelbury Manor) leased land part of which abutted on (his) land to the Company and their director George Hancock for a period of 27 years at a minimum rent of £50.[14] The agreement stated that Quarries are being worked in the parish of Monkton Farleigh and it is desirable that the produce … should be conveyed to the Great Western Railway without passing over the public parish roads. In the event, the Company kept the lease until its surrender on 29 April 1904 when it was leased to The Bath Stone Firms for a period of 21 years.[15]

Sale of Ashley Estate, 1912

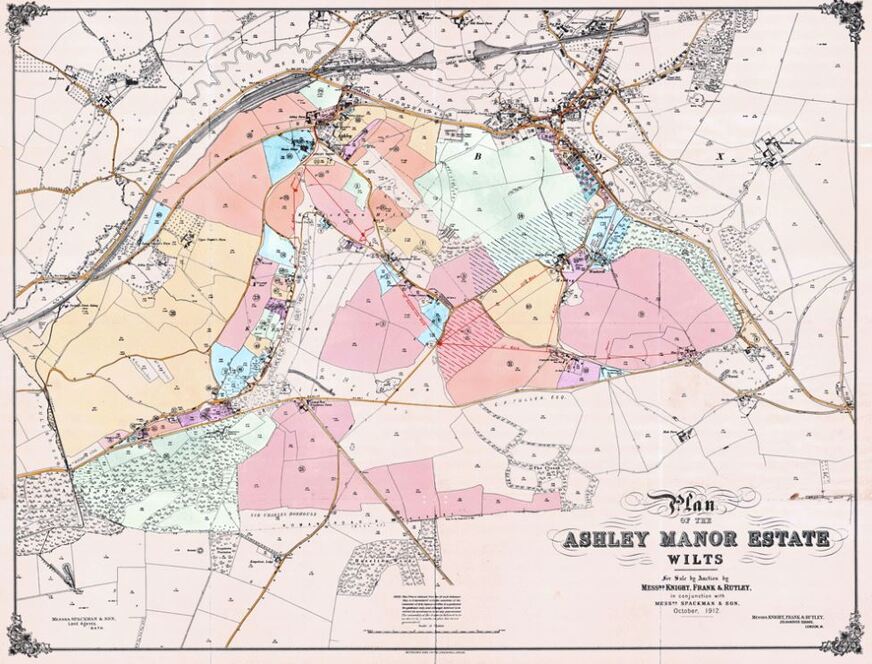

As income from stone quarrying diminished, the family had little option but to follow a different business plan: a concerted effort to exit their landholdings, not to supplement their income in Box but as a way of avoiding the costs of maintenance and improvement. The 1912 auction of the Ashley Estate comprised 73 individual plots and 900 acres of land and was by instruction from George E Northey, Esq. Although the actual seller was not named, it is presumed that most of the land comprised the trust land of the Northey estate. The sale by Knight, Frank & Rutley in the Assembly Rooms, Bath, offered to sell the estate as a whole or in lots. It was clearly targeted at a major purchaser with references to Sporting and Manorial Estates and emphasised the Rent Roll of about £1,600 per annum.

The sale included seven farms - at Prospect, Blue Vein, Henley, Spencer’s, Ashley, Kingsdown and Upper Sheylor’s – as well as a number of smallholdings. We see later that at least Ashley and Henley Farms do not appear to have sold. The auction also offered Longsplatt Quarry, and timber stocks - 68 acres of Ashley Wood and 20 at White Wood - as well as Box Water Works in Ashley, said to have Valuable Goodwill and average net annual profits of £200 pa. More personal was the disposal of Ashley Manor, then let as a boys’ school to Rev AV Gregoire. Not that this was an emotive issue for George Edward Northey who had left home by the time that his parents lived here, unlike the reaction of some of his younger brothers who regarded it as their childhood home.

Sale of Ashley Estate, 1912

As income from stone quarrying diminished, the family had little option but to follow a different business plan: a concerted effort to exit their landholdings, not to supplement their income in Box but as a way of avoiding the costs of maintenance and improvement. The 1912 auction of the Ashley Estate comprised 73 individual plots and 900 acres of land and was by instruction from George E Northey, Esq. Although the actual seller was not named, it is presumed that most of the land comprised the trust land of the Northey estate. The sale by Knight, Frank & Rutley in the Assembly Rooms, Bath, offered to sell the estate as a whole or in lots. It was clearly targeted at a major purchaser with references to Sporting and Manorial Estates and emphasised the Rent Roll of about £1,600 per annum.

The sale included seven farms - at Prospect, Blue Vein, Henley, Spencer’s, Ashley, Kingsdown and Upper Sheylor’s – as well as a number of smallholdings. We see later that at least Ashley and Henley Farms do not appear to have sold. The auction also offered Longsplatt Quarry, and timber stocks - 68 acres of Ashley Wood and 20 at White Wood - as well as Box Water Works in Ashley, said to have Valuable Goodwill and average net annual profits of £200 pa. More personal was the disposal of Ashley Manor, then let as a boys’ school to Rev AV Gregoire. Not that this was an emotive issue for George Edward Northey who had left home by the time that his parents lived here, unlike the reaction of some of his younger brothers who regarded it as their childhood home.

Sale of Box Estate, 1919 and 1923

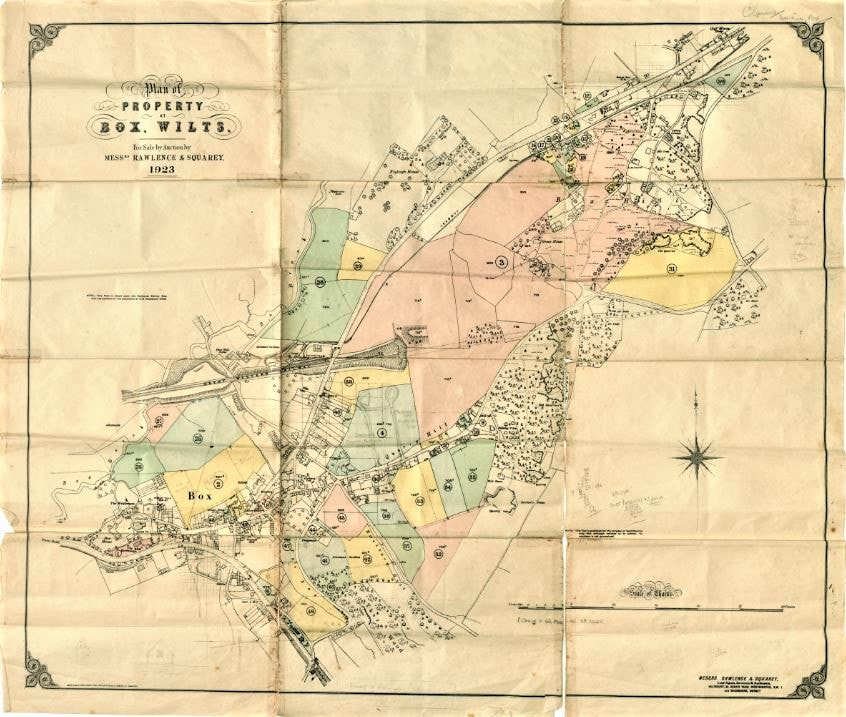

The trustees put further marketing on hold in the run up to the First World War. Efforts to find an individual purchaser of the entire estate was out of the question by the time that peace came, the prospects of selling were even worse and prices significantly lower. George Edward agreed to the disposal by auction of huge tranches of property and the Box Estate was auctioned in two parts: in 1919 the Southern Area and in 1923 Box Hill and Eastern Area of the village.

The sale in 1919 could hardly have been worse-timed after the economic disruption of the First World War. The auction was conducted by Daniel Smith, Oakley & Garrard. Shortly after the sale, farming tenants were given notice to quit and in February 1920 the Chippenham livestock agents, Tilley, Culverwell and Parrott, gave notice of the sale of the entire live and dead stock of Henley and Ashley Farms, the farms having been sold.[16] In 1919 by separate treaty, George Jardine Kidston bought Hazelbury Manor, which had fallen into decline.

The trustees put further marketing on hold in the run up to the First World War. Efforts to find an individual purchaser of the entire estate was out of the question by the time that peace came, the prospects of selling were even worse and prices significantly lower. George Edward agreed to the disposal by auction of huge tranches of property and the Box Estate was auctioned in two parts: in 1919 the Southern Area and in 1923 Box Hill and Eastern Area of the village.

The sale in 1919 could hardly have been worse-timed after the economic disruption of the First World War. The auction was conducted by Daniel Smith, Oakley & Garrard. Shortly after the sale, farming tenants were given notice to quit and in February 1920 the Chippenham livestock agents, Tilley, Culverwell and Parrott, gave notice of the sale of the entire live and dead stock of Henley and Ashley Farms, the farms having been sold.[16] In 1919 by separate treaty, George Jardine Kidston bought Hazelbury Manor, which had fallen into decline.

The 1923 sale offered 48 individual lots belonging to Major General Sir Edward Northey of Epsom comprising 21 cottages and 143 acres of farm and accommodation land, together with six lots belonging to the personal estate of George Edward, including five cottages. In total the 1923 sale by Rawlence and Squarey (who later became Humberts of Chippenham) was adjudged to be a success, disposing of 41 lots which realised £8,862.[17] But it was only achieved by allowing purchasers to pay by twenty half-yearly instalments plus interest.

1923 Sale Particulars Above Left: The Hermitage and Right: Glendale at foot of Quarry Hill is now called Peartree Cottage (courtesy Margaret Wakefield)

The biggest lots were Manor Farmhouse, the Hermitage in the centre of Box, and Grove Farm on Box Hill. The sale included the house and six acres of Mead Farm (now called The Manor Farm) but not the land immediately to the north of the house (now called The Rec) which was sold to George Kidston in 1925 for the benefit of the village, subject to an agreement with the Cricket Club.[18] In the centre of the village, the family sold their Estate Office (next door to Clock House) and the adjacent property which had been let to the Union of London and Smith’s Bank (all now demolished and replaced by the old Co-op building).

Some of the land fronting the London and Bath Road (the villas on the London Road) was put up for development in the 1923 auction, other plots of land were sold which were only developed after the Second World War, such as The Ley and a paddock off the A4 bought by the Lambert family who held it until they built Moonrakers there in 1953.

Sale of Ditteridge Properties

By the end of the Second World War the only substantial assets left were in Ditteridge. Armand Northey decided not to keep Cheney Court and it was sold in 1948 along with Hill House Farm (now called Jamie’s Farm). The family kept some of the farmland for the income from tenants but in 1964 Slades Farm was sold.[19] The Northey came to an end in 2018 when the last remaining member of the family sold their residence in Kingsdown House. Now, there is no land or building in the village in the family’s possession and no lord of the manor of Ashley and Box.

The Northey family’s withdrawal from Box was due to long-term trends, lack of investment into the properties, and overdependence on military service for experience. It was a similar story for many of their contemporaries and it would be incorrect to blame them for failing to retain their assets. In Box, the Northey family were landed parish gentry rather than national aristocracy and they were close to their tenants. They suffered directly with rent arrears, the collapse of mixed sheep and corn farming, vacated tenancies and falling rent rolls. The Northeys survived as best they could for as long as they could until they had nothing left to sell.

Some of the land fronting the London and Bath Road (the villas on the London Road) was put up for development in the 1923 auction, other plots of land were sold which were only developed after the Second World War, such as The Ley and a paddock off the A4 bought by the Lambert family who held it until they built Moonrakers there in 1953.

Sale of Ditteridge Properties

By the end of the Second World War the only substantial assets left were in Ditteridge. Armand Northey decided not to keep Cheney Court and it was sold in 1948 along with Hill House Farm (now called Jamie’s Farm). The family kept some of the farmland for the income from tenants but in 1964 Slades Farm was sold.[19] The Northey came to an end in 2018 when the last remaining member of the family sold their residence in Kingsdown House. Now, there is no land or building in the village in the family’s possession and no lord of the manor of Ashley and Box.

The Northey family’s withdrawal from Box was due to long-term trends, lack of investment into the properties, and overdependence on military service for experience. It was a similar story for many of their contemporaries and it would be incorrect to blame them for failing to retain their assets. In Box, the Northey family were landed parish gentry rather than national aristocracy and they were close to their tenants. They suffered directly with rent arrears, the collapse of mixed sheep and corn farming, vacated tenancies and falling rent rolls. The Northeys survived as best they could for as long as they could until they had nothing left to sell.

References

[1] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.106

[2] FML Thompson, English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century, 1963, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.292

[3] FML Thompson, English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century, p.308-10

[4] http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1882/38/pdfs/ukpga_18820038_en.pdf, section 3

[5] FML Thompson, English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century, p.332

[6] Courtesy Margaret Wakefield, Abstract of Title to Moonrakers, sold in the 1923 auction

[7] See Mullins Family article

[8] Wiltshire History Centre, 1126/45

[9] Courtesy Julian Orbach from his unpublished research to update Pevsner Architectural Guide to Buildings of England: Wiltshire

[10] Courtesy Julian Orbach, as above

[11] Wiltshire Heritage Centre

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 6 December 1888

[13] Derek Hawkins, Bath Stone Quarries, 2011, Folly Books, p.65-66

[14] Memorandum of Agreement, 2 March 1881, Wiltshire History Centre

[15] Surrender Agreement, Wiltshire History Centre

[16] The Western Gazette, 13 February 1920

[17] The Wiltshire Times, 2 June 1923

[18] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.52

[19] Countryside Treasures, Wiltshire History Centre

[1] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.106

[2] FML Thompson, English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century, 1963, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.292

[3] FML Thompson, English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century, p.308-10

[4] http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1882/38/pdfs/ukpga_18820038_en.pdf, section 3

[5] FML Thompson, English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century, p.332

[6] Courtesy Margaret Wakefield, Abstract of Title to Moonrakers, sold in the 1923 auction

[7] See Mullins Family article

[8] Wiltshire History Centre, 1126/45

[9] Courtesy Julian Orbach from his unpublished research to update Pevsner Architectural Guide to Buildings of England: Wiltshire

[10] Courtesy Julian Orbach, as above

[11] Wiltshire Heritage Centre

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 6 December 1888

[13] Derek Hawkins, Bath Stone Quarries, 2011, Folly Books, p.65-66

[14] Memorandum of Agreement, 2 March 1881, Wiltshire History Centre

[15] Surrender Agreement, Wiltshire History Centre

[16] The Western Gazette, 13 February 1920

[17] The Wiltshire Times, 2 June 1923

[18] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.52

[19] Countryside Treasures, Wiltshire History Centre