Second Elizabethan Age Alan Payne December 2022

Girls growing up in 1950s Box often had the name Elizabeth or Margaret, popularised by the monarchy. Left to Right, Back row: Elizabeth Bell (vicar's daughter), Ann Ball from Hazelbury Hill, Margaret Lambert, Elizabeth Grayson, Andrea Mortimer. Front Row: Diana Brunt and Karen Griffin (courtesy Margaret Wakefield)

Nostalgia often gives a distorted image of history, often throwing up heroes and “Golden Ages” with the benefit of hindsight.

For children born after the Second World War, the sovereign they knew was Queen Elizabeth II. The period since 1953 has been a long and varied time, one of the only stable factors being the queen herself.

For children born after the Second World War, the sovereign they knew was Queen Elizabeth II. The period since 1953 has been a long and varied time, one of the only stable factors being the queen herself.

In October 1951 the Conservatives returned to power promising to lift unnecessary wartime controls. It was a hopeful, new start for children after wartime deprivation when sweets came off rationing in February 1953. Coronation events didn’t start well, however. Following the death of Elizabeth’s father George VI in February 1952, there was a period of mourning before any festivities but this was nearly further postponed by the death of her grandmother Queen Mary in March 1953.

There were unreserved celebrations on the very morning of the coronation when the British Commonwealth celebrated the report in The Times by Jan Morris (then known as James Morris) announced the climbing of Everest by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay.

There were unreserved celebrations on the very morning of the coronation when the British Commonwealth celebrated the report in The Times by Jan Morris (then known as James Morris) announced the climbing of Everest by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay.

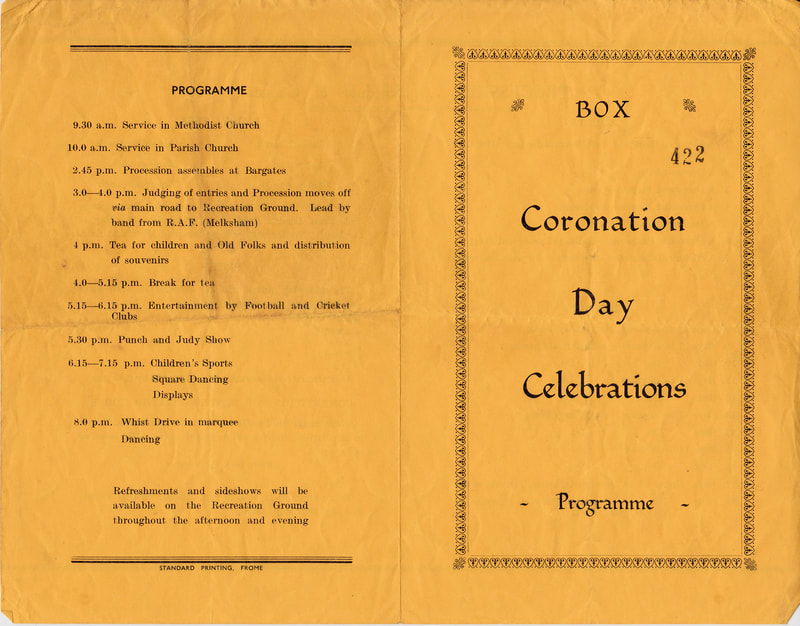

Box’s Coronation Celebrations, 1953

It was little wonder that residents of Box were keen to enjoy the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on 2 June 1953. A village committee was set up in February 1953 and the vicar Rev Lendon Bell reported the arrangements at Box Church: special prayers on Trinity Sunday 31 May, a youth service on the Monday, the eve of the young princess’ coronation and a special Coronation Service for all members of the parish on the actual day with Communion at 8am and a parish service at 10am on Tuesday 2 June 1953.[1] This service was expected to last 40 minutes followed by the televised broadcast from Westminster Abbey, to be viewed by some in Box thanks to a television set loaned and installed by Leslie and Nigel Bence in the church. The 1950s sets were small and the volume poor, so silence was requested by the congregation which was limited to 100 people. The vicar was able to report that the televising of the Westminster Abbey service was unique and enabled by the achievements of science to view and hear the solemn service.[2] One small problem was the difficulty of hiring a television set as so many of the public wanted to see it in their own homes.

The weather on Coronation Day 2 June didn’t play ball, being dull, cold and overcast with a chill wind. Nonetheless, probably the largest fancy dress procession ever seen in Box, made its way from Bargates to the Rec with 150 children and adults behind the Melksham RAF Band.[3] In the afternoon 440 children sat down for tea on The Rec, when there were various entertainments: Box School children put on folk dancing supervised by headmaster Mr Arthur Adams, Bill Peters lent three ponies for rides, and the Scouts and Girl Guides entertained with a beacon on high ground after dark.

It was little wonder that residents of Box were keen to enjoy the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on 2 June 1953. A village committee was set up in February 1953 and the vicar Rev Lendon Bell reported the arrangements at Box Church: special prayers on Trinity Sunday 31 May, a youth service on the Monday, the eve of the young princess’ coronation and a special Coronation Service for all members of the parish on the actual day with Communion at 8am and a parish service at 10am on Tuesday 2 June 1953.[1] This service was expected to last 40 minutes followed by the televised broadcast from Westminster Abbey, to be viewed by some in Box thanks to a television set loaned and installed by Leslie and Nigel Bence in the church. The 1950s sets were small and the volume poor, so silence was requested by the congregation which was limited to 100 people. The vicar was able to report that the televising of the Westminster Abbey service was unique and enabled by the achievements of science to view and hear the solemn service.[2] One small problem was the difficulty of hiring a television set as so many of the public wanted to see it in their own homes.

The weather on Coronation Day 2 June didn’t play ball, being dull, cold and overcast with a chill wind. Nonetheless, probably the largest fancy dress procession ever seen in Box, made its way from Bargates to the Rec with 150 children and adults behind the Melksham RAF Band.[3] In the afternoon 440 children sat down for tea on The Rec, when there were various entertainments: Box School children put on folk dancing supervised by headmaster Mr Arthur Adams, Bill Peters lent three ponies for rides, and the Scouts and Girl Guides entertained with a beacon on high ground after dark.

Festivities on The Rec in 1953 Left: Ossie Butt, Les Bawtree and Cyril Witter Nichols and Right Ossie Butt (courtesy Ken and Maureen Boulton)

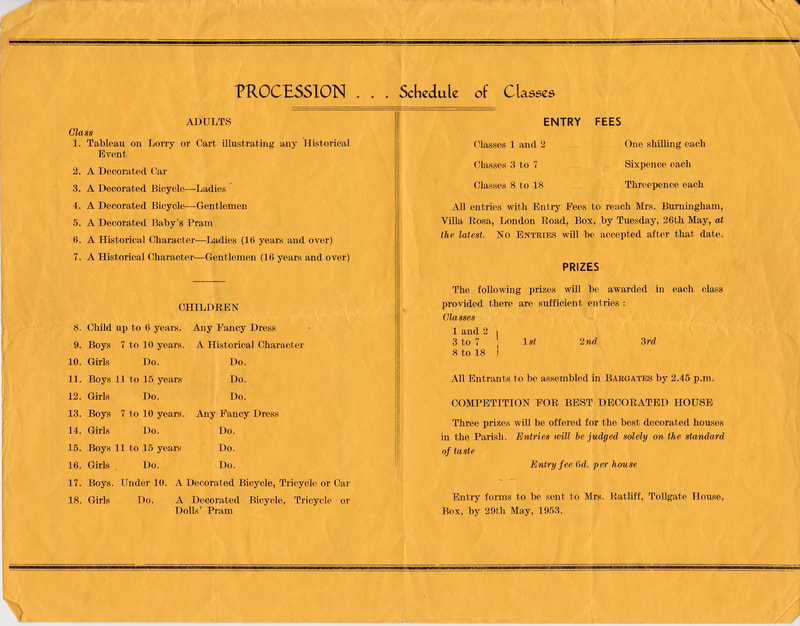

A new approach was made to dressing up with prizes for decorated cars, bicycles (male and female separately) and prams (with an extension to decorated tricycles and doll’s prams for children). There was also a new idea with decorated houses in the village. In order to pay for the prizes, entrants were asked to pay an entry fee varying between 3d and 1 shilling.

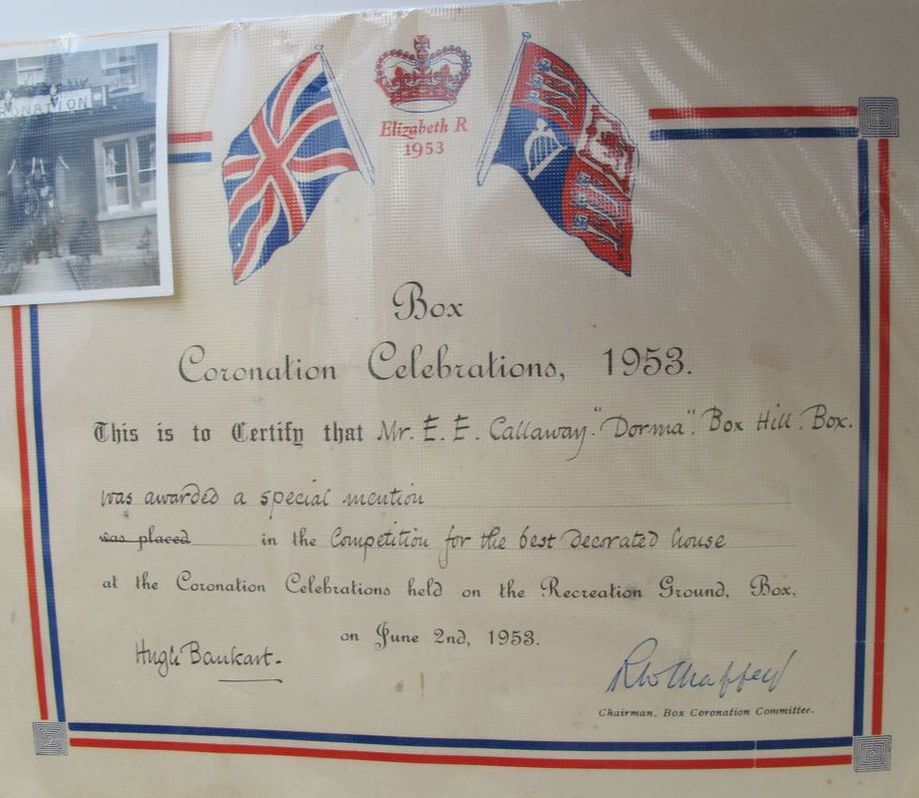

Dorma on Box Hill received a special mention for decoration (courtesy Eric Callaway)

The event also offered prizes for the best dressed villagers, tea for OAPs, comedy football and cricket entertainment, then a whist drive and dancing in a marquee on The Rec. The marquee on The Rec was laid out for a tea for children under 15 years and every place setting had a free souvenir mug. Despite all attempts at jollity, it was a rather formal event.

Programme of events in Coronation Weekend 1953 (courtesy Eric Callaway)

Teenagers

It is difficult to list all the changes in British society from the coronation until the Queen's death. One of the most telling was the invention of the word Teenagers in the 1950s and 60s. It was a new grouping based on peace, higher standards of education and prosperity. Bitterly opposed by some people, the new youth movement was questioned for its Ban the Bomb stance, folk clubs and Edwardian clothing, all of which excluded the wartime generation. The roots in Box started with educational reforms.

The village was changed when secondary education moved out of the village to Corsham and Bradford in 1954. Undoubtedly, education was improved but there was also a real loss: travel to distant schools became difficult in poor weather and older children were distanced from village life. Instead, the village had to make communal efforts to care for its young residents.

The old Scout Hut on the Devizes Road was demolished in September 1954 and a new hall was organised by Phil Lambert and the troop early the following year.[4] The old hall had provided good service since it was moved there from Ashley House in 1911 but had been used extensively during the war and was unfit for further use. There was also considerable success for the Box Girls Club. In 1953 there were Grades A+ for embroidery, and considerable musical success for Frances Cook, Anna Grayson and Ann Hayward in piano and recorder solos and in written work. There were also prizes at the Corsham Eisteddfod.[5]

But none of these can compare with the activity of Box Boys Club. It wasn’t a stuffy affair, more the birth of Box teenagers. There was a skiffle and rock ’n roll dance at the club every Friday and the club’s instrumental rhythm group The Four Specs auditioned at Bristol for the Frankie Vaughan trophy. A Judo instructor held classes and in October 1959 club member, Rodney Brickell, was selected to represent the County of Wiltshire to present messages to HRH the Duke of Gloucester in London. The club went from success to success and it was decided to fundraise to convert an old factory in Dyer’s Yard in the Market Place into a clubhouse for the Box Boys’ Club. By September 1964 £1,900 had been paid to the builders and the premises was opened in October of that year. It was a wonderful success story for such a small village, recognised by the visit on 27 October 1967 of Frankie Vaughan, nationally famous singer and president of the National Association of Boys Clubs.[6] But by the early 1970s the building was running down and a major overhaul was needed.[7] In the event, it was just a tidy-up with cleaning out access to the Upper Room and a lick of paint downstairs. The building still exists, being developed into the Jubilee Youth Centre in June 1977 as part of the fundraising celebrations for the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II.[8] The newly restored building was opened in October 1978 by the county’s Deputy Lieutenant, Rear Admiral Desmond Nixon, who lived in Ashley and had been the Chairman of Box’s Silver Jubilee Committee.

The problem of teenagers seems pretty innocuous to us today. Teddy Boys, dressed to the nines in Edwardian long coats and DAs (duck-arse) hairstyles, whilst listening to Frankie Vaughan singing Green Door as he kicked his leg in the air, producing howls of admiration from teenage girls.

It is difficult to list all the changes in British society from the coronation until the Queen's death. One of the most telling was the invention of the word Teenagers in the 1950s and 60s. It was a new grouping based on peace, higher standards of education and prosperity. Bitterly opposed by some people, the new youth movement was questioned for its Ban the Bomb stance, folk clubs and Edwardian clothing, all of which excluded the wartime generation. The roots in Box started with educational reforms.

The village was changed when secondary education moved out of the village to Corsham and Bradford in 1954. Undoubtedly, education was improved but there was also a real loss: travel to distant schools became difficult in poor weather and older children were distanced from village life. Instead, the village had to make communal efforts to care for its young residents.

The old Scout Hut on the Devizes Road was demolished in September 1954 and a new hall was organised by Phil Lambert and the troop early the following year.[4] The old hall had provided good service since it was moved there from Ashley House in 1911 but had been used extensively during the war and was unfit for further use. There was also considerable success for the Box Girls Club. In 1953 there were Grades A+ for embroidery, and considerable musical success for Frances Cook, Anna Grayson and Ann Hayward in piano and recorder solos and in written work. There were also prizes at the Corsham Eisteddfod.[5]

But none of these can compare with the activity of Box Boys Club. It wasn’t a stuffy affair, more the birth of Box teenagers. There was a skiffle and rock ’n roll dance at the club every Friday and the club’s instrumental rhythm group The Four Specs auditioned at Bristol for the Frankie Vaughan trophy. A Judo instructor held classes and in October 1959 club member, Rodney Brickell, was selected to represent the County of Wiltshire to present messages to HRH the Duke of Gloucester in London. The club went from success to success and it was decided to fundraise to convert an old factory in Dyer’s Yard in the Market Place into a clubhouse for the Box Boys’ Club. By September 1964 £1,900 had been paid to the builders and the premises was opened in October of that year. It was a wonderful success story for such a small village, recognised by the visit on 27 October 1967 of Frankie Vaughan, nationally famous singer and president of the National Association of Boys Clubs.[6] But by the early 1970s the building was running down and a major overhaul was needed.[7] In the event, it was just a tidy-up with cleaning out access to the Upper Room and a lick of paint downstairs. The building still exists, being developed into the Jubilee Youth Centre in June 1977 as part of the fundraising celebrations for the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II.[8] The newly restored building was opened in October 1978 by the county’s Deputy Lieutenant, Rear Admiral Desmond Nixon, who lived in Ashley and had been the Chairman of Box’s Silver Jubilee Committee.

The problem of teenagers seems pretty innocuous to us today. Teddy Boys, dressed to the nines in Edwardian long coats and DAs (duck-arse) hairstyles, whilst listening to Frankie Vaughan singing Green Door as he kicked his leg in the air, producing howls of admiration from teenage girls.

|

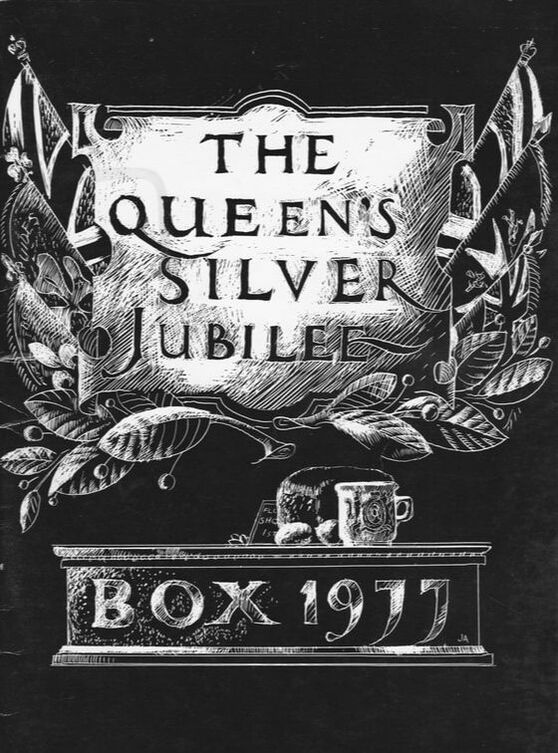

Silver Jubilee, June 1977

The 25th anniversary of the accession of the Queen was an altogether more ambitious event, reflecting changed economic and social circumstances in Britain during the 25 years of Queen Elizabeth’s reign. The celebrations were less religious in content and much longer, altogether more of a community celebration. The Radio Times produced a souvenir edition and described the event as A jubilant burst of celebrations .. all over the country officially marks the start of Jubilee Week revelries.[9] In April 1977 the event was launched by Prince Charles (then an unmarried man of 28) to raise funds for a National Jubilee Appeal (now called The Queen’s Trust) in support of young people’s work in low-income communities. There were several innovative events: a series of bonfires throughout the country, an illuminated River Pageant along The Thames, and jubilee television shows such as Jubilee Songs of Praise and for children Jubilee Jackanory. Amazingly in the same year, Liverpool became the first English side to win the European Cup, Virginia Wade won Wimbledon and Red Rum triumphed for the third time in the Grand National. Box and the whole country prepared to party. (All silver jubilee photos courtesy Phil Martin) |

Box’s contribution to the National Appeal of £350 (today worth £2,500) was covered almost immediately by donations from two local firms, Spafax Ltd and Flaxyard Ltd, a real estate developer.[10] Their generosity freed house-to-house subscriptions and allowed local donations of £1,800 (today £13,000) to be used on the conversion of the Market Place building.

Box Parish Council led the way in planning the village celebrations in 1977.[11] They put out a request for houses to be decorated with Union Jacks and bunting. The agenda for the celebrations comprised:

Friday 3 June: Decoration of houses, street parties start, evening disco and selection of a Jubilee Queen

Saturday 4 June: Flower Festivals in the Church and Selwyn Hall, Home Produce & Flower Show in Selwyn Hall, sports on The Rec, Pig Roast and an informal dance (barn dance) in the Selwyn Hall

Sunday 5 June: Combined Church service and Exhibition in Box School by local clubs

Monday 6 June: Carnival Floats, children’s tea party and Grand Jubilee Ball in the evening

Tuesday 7 June: Additional Bank Holiday but left as a free day for recovery and watching the royal procession in London.

The coordination of events was through a central steering committee led by Rear-Admiral Desmond Nixon of Ashley supported by sub-committees for each event: Barbara Higgens publicity, Penny Newboult secretary, Margaret Rousell treasurer. Every event had its own organiser: Box headteacher Russ Allbrook responsible for sports, Roy Hodges for exhibitions, Phil Lambert for games and Ron Banks for the Jubilee Ball.

Friday 3 June: Decoration of houses, street parties start, evening disco and selection of a Jubilee Queen

Saturday 4 June: Flower Festivals in the Church and Selwyn Hall, Home Produce & Flower Show in Selwyn Hall, sports on The Rec, Pig Roast and an informal dance (barn dance) in the Selwyn Hall

Sunday 5 June: Combined Church service and Exhibition in Box School by local clubs

Monday 6 June: Carnival Floats, children’s tea party and Grand Jubilee Ball in the evening

Tuesday 7 June: Additional Bank Holiday but left as a free day for recovery and watching the royal procession in London.

The coordination of events was through a central steering committee led by Rear-Admiral Desmond Nixon of Ashley supported by sub-committees for each event: Barbara Higgens publicity, Penny Newboult secretary, Margaret Rousell treasurer. Every event had its own organiser: Box headteacher Russ Allbrook responsible for sports, Roy Hodges for exhibitions, Phil Lambert for games and Ron Banks for the Jubilee Ball.

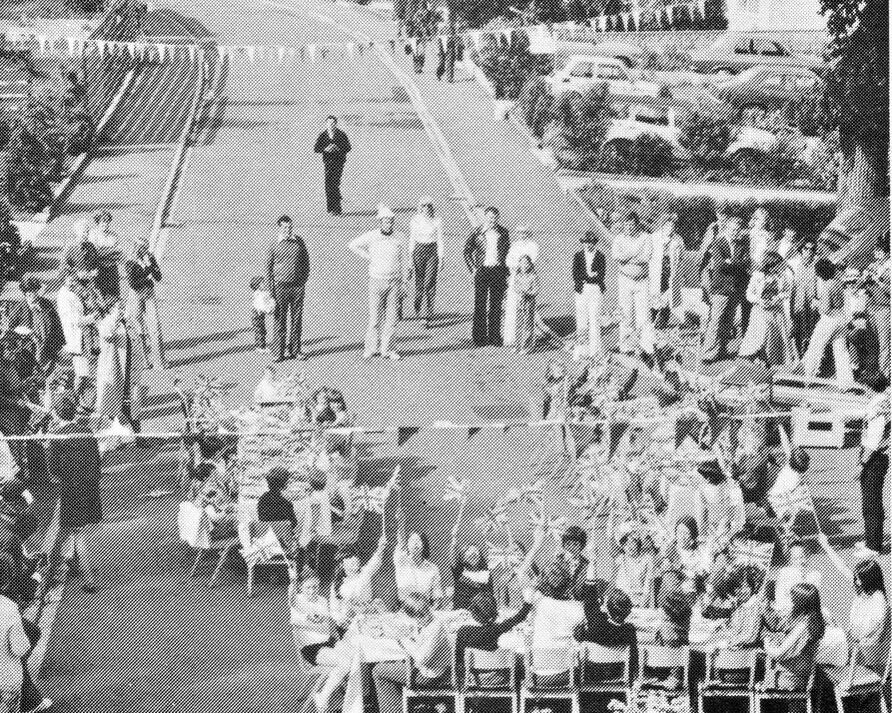

Street parties closed many roads after getting relevant permissions, possibly left Box Hill and right Bargates (courtesy 1977 brochure)

For many, the first event was a local street party planned for Friday but street closure was spread onto different days to allow road flow. In the evening the Jubilee disco in the Selwyn Hall danced to the music of Cyril’s Roadshow attended by about 200 people. Sally Bridger was elected Jubilee Queen with maids of honour Anna Gelsthorpe and Tina Hyde.

Saturday offered exhibitions when the churches and Parish Council Offices put on flower festivals and a Flower and Produce show was organised in the Selwyn Hall, the first to be held since 1956. Sports events were held on The Rec with the usual mix of It’s a Knockout, children’s games and tug-of-war on an endless rope, involving most spectators. To ensure it was well cooked, a pig roast started cooking at 11am which continued until the first slice went to the Jubilee Queen at 8.15pm, signifying the start of the barbeque, followed by a Jubilee Barn Dance at the Selwyn Hall.

Saturday offered exhibitions when the churches and Parish Council Offices put on flower festivals and a Flower and Produce show was organised in the Selwyn Hall, the first to be held since 1956. Sports events were held on The Rec with the usual mix of It’s a Knockout, children’s games and tug-of-war on an endless rope, involving most spectators. To ensure it was well cooked, a pig roast started cooking at 11am which continued until the first slice went to the Jubilee Queen at 8.15pm, signifying the start of the barbeque, followed by a Jubilee Barn Dance at the Selwyn Hall.

Above Left: Pig Roast and Right: Barn Dance in Selwyn Hall (courtesy 1977 brochure)

The weather became cloudy and cool on the Sunday. Despite this, a combined open-air church service attracted 500 people on the Sunday. With support by the Over-60s choir and the Marshfield Brass Band, there were processions from youth organisations around The Rec. For those who wanted a quieter time, Box School exhibited artefacts of royal events from Box’s history records. It was a real Box village gathering.

Above Left: Flower Festival in Ditteridge Church and Right: Royal Exhibition at Box School (courtesy 1977 brochure)

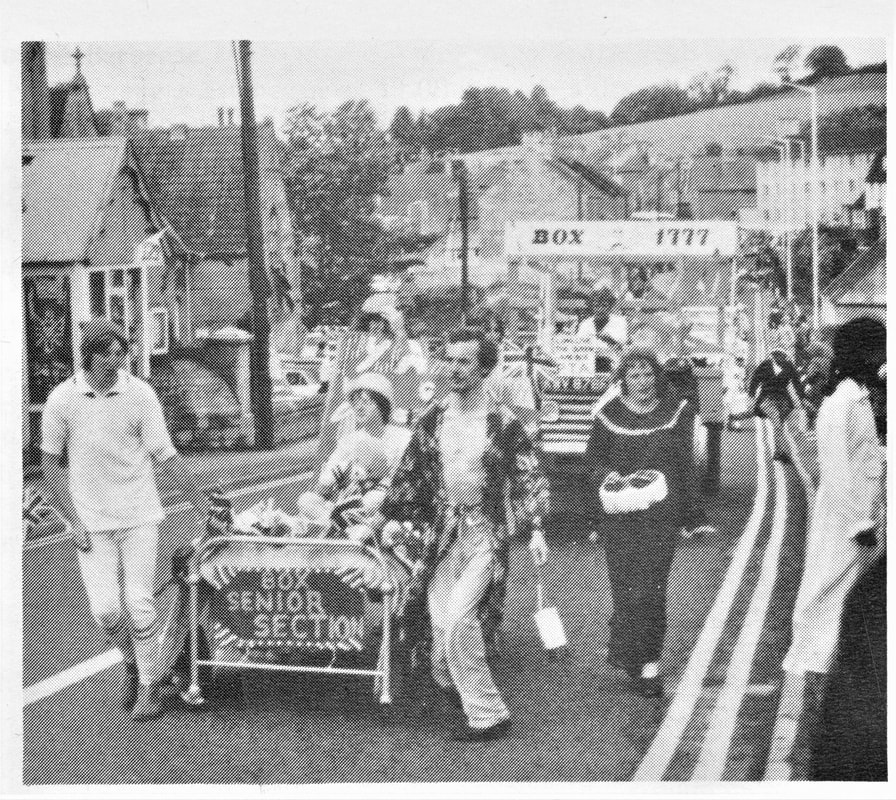

The Grand Procession was the centrepiece of Monday’s events. The parade started at Bargates and processed along the High Street. You can see below the procession going past The Shed between the school and Hardy House.

Above: Photos of the Grand Procession, showing the wooden shop between the school and Hardy House

Below: Preparing floats and Left: Lap of Honour (all 1977 brochure photos courtesy Phil Martin)

Below: Preparing floats and Left: Lap of Honour (all 1977 brochure photos courtesy Phil Martin)

The village was so justifiably pleased with the outcome that they produced a special brochure, from which these details were taken. For a four-day celebration in variable weather, it was a great community event.

Queen Elizabeth has had several jubilees: silver in 1977; golden in 2002, when the Saturday night dance was promoted as a "Red, White & Blue Bash"; diamond in 2012; and, of course, the first British monarch to have a platinum jubilee in 2022.

We haven't detailed the later events as we cut off the historical details at approximately the millenium. Each of the events has been celebrated in a different way, championed by different residents and reflecting an ever-changing society enjoying increased affluence since the Second World War. One of the few constants has been the use of The Rec for communal gatherings, still rather a novelty in 1953.

We haven't detailed the later events as we cut off the historical details at approximately the millenium. Each of the events has been celebrated in a different way, championed by different residents and reflecting an ever-changing society enjoying increased affluence since the Second World War. One of the few constants has been the use of The Rec for communal gatherings, still rather a novelty in 1953.

References

[1] Parish Magazine, June 1953

[2] Parish Magazine, July 1953

[3] The Wiltshire Times, 6 June 1953

[4] Parish Magazine, Dec 1954

[5] Parish Magazine, June 1953

[6] Parish Magazine, October 1967

[7] Parish Magazine, January 1973

[8] Parish Magazine, June 1977

[9] Radio Times, 4-10 June 1977

[10] Parish Magazine, June 1977

[11] Parish Council minutes, June 1977

[1] Parish Magazine, June 1953

[2] Parish Magazine, July 1953

[3] The Wiltshire Times, 6 June 1953

[4] Parish Magazine, Dec 1954

[5] Parish Magazine, June 1953

[6] Parish Magazine, October 1967

[7] Parish Magazine, January 1973

[8] Parish Magazine, June 1977

[9] Radio Times, 4-10 June 1977

[10] Parish Magazine, June 1977

[11] Parish Council minutes, June 1977