Cheney Court Mysteries Alan Payne, February 2021

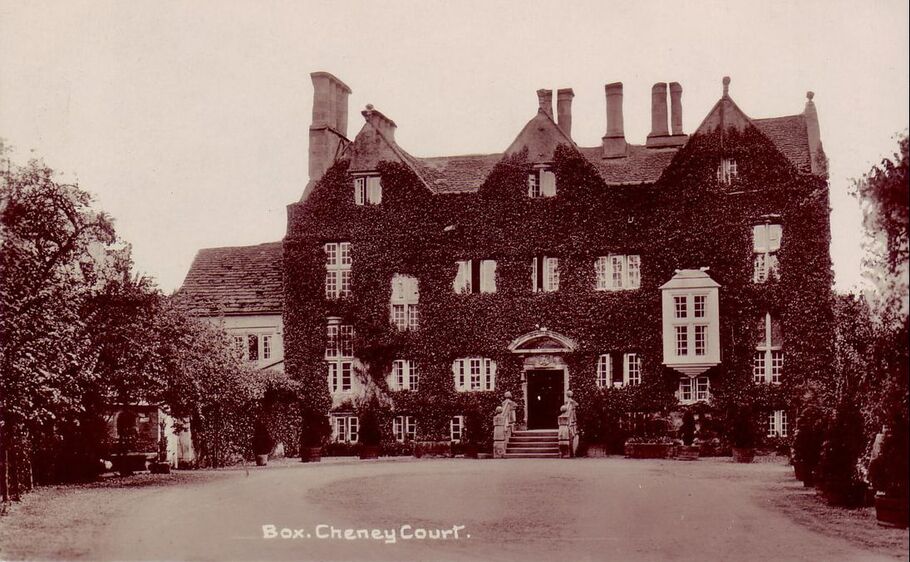

Cheney Court, Ditteridge, is a fabulous Grade II* property, with origins believed to go back to Sir Edmund Cheney in the Tudor 1400s.[1] The flat-topped chimneys have Tudor roses carved at each corner commemorating its early origins as does its construction partly in rubble stone rather than ashlar blocks. Most of the present house was rebuilt by its new Georgian owners, the Speke family, and later George Edward Northey, lord of Box manor, lived there. But the story of the house is much stranger than these bare facts.

Mysteries of the House’s Origins

Although it is sited close to Ditteridge Church, Cheney Court is not related to St Christopher’s, Ditteridge, but is part of the parish of Box, a mile away and accessed via a rather circuitous route. Accordingly, the occupants of the house paid their church tithes and owed their allegiance to St Thomas à Becket for centuries possibly from the Saxon period, through the Reformation and up to present times. This wasn’t just of financial interest because the parish priest was responsible for the care of souls under his jurisdiction, administering sacraments and absolution to the dying, and the burial around the parish church of bodies awaiting Resurrection. Nobody knows how or when the parish structure arose and scholars have speculated that the parish of Box might have been carved out of an earlier Ditteridge parish (or vice versa).

Although it is sited close to Ditteridge Church, Cheney Court is not related to St Christopher’s, Ditteridge, but is part of the parish of Box, a mile away and accessed via a rather circuitous route. Accordingly, the occupants of the house paid their church tithes and owed their allegiance to St Thomas à Becket for centuries possibly from the Saxon period, through the Reformation and up to present times. This wasn’t just of financial interest because the parish priest was responsible for the care of souls under his jurisdiction, administering sacraments and absolution to the dying, and the burial around the parish church of bodies awaiting Resurrection. Nobody knows how or when the parish structure arose and scholars have speculated that the parish of Box might have been carved out of an earlier Ditteridge parish (or vice versa).

The origin of early settlement in the area is also uncertain with the known medieval facts given in the appendix below. However, the Georgians reported a much earlier occupation and claimed to have discovered the remains of a Roman villa at Cheney Court.[2] No sign of the villa has emerged since then except for some artefacts in the vicinity and an intriguing aerial photograph which revealed the outline of a building in an adjacent field. Splinters of Roman Samian ware have also been found elsewhere at Ditteridge.[3]

A curious architectural anomaly of the present house built by George Speke in the 1620s is that part of the fabulous appearance is a sham.[4] The windows on the left are staggered to provide light in the staircase, but the windows on the right are false, matching the left but without a staircase behind. The Royal Commission on Historic Monuments described the house as: a provincial builder’s attempt to build a house to the compact, rectangular double-pile plan that was becoming increasingly widespread during the 17th century but whose acceptance throughout the country was affected by the strength of existing building traditions.

Royal Mystery

The contemporary writer, John Aubrey, asserted in the late 1600s that: There is a tradition that (Cheney) Court, which is large and surrounded by a high wall, was used for some military purpose in the Civil Wars.[5] This unproven comment has usually been explained as gossip but there are numerous assertions that the Speke family were Catholic sympathisers at a time when Protestantism was in the ascendancy in England.

In 1644 during the English civil war, it was reported that Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I, hid in a barn at the Court as she fled from Oxford to Exeter on her way to seek refuge in France. Based on the diary of Sir William Dugdale on 17 April 1644, the story goes that The Queen went out of Oxford towards Exeter. The King went with her to Abingdon where she lay the night. It was not safe for her to stay in Oxford, where King Charles was preparing for battle against the Roundheads, and she fled west. When they parted at Abingdon, they would never see each other again, before Charles’ trial in parliament and his execution in 1649. There is no direct mention of Cheney Court in any of the documents.[6]

Nonetheless the legend persists and has grown over time. The Bath Chronicle of 1910 recorded: A peculiarity of the entrance hall is that on the left is a raised dais, which it is supposed was erected for the Queen (Henrietta Maria), the lower part of the Hall being used by the Royal retinue.[7] In 1928 the owner, George Edward Northey, added to the story that the dining room was previously a chapel with a small hole (a leper’s squint) through which offerings could be made to a Catholic priest and the Eucharist received without seeing the priest’s face.[8]

Letting Cheney Court

Dame Anne Speke, widow of Sir Hugh Speke, probably lived here from 1672 until her death in 1686 but after the Speke family sold their estate to the Northeys about 1726, the house was largely used as an investment property for over a century.[9] The Northeys had large landed interests including Woodcote House, Epsom, Surrey and a property at Compton Bassett. For a long time, they let out Cheney Court as a desirable house convenient to Bath, suitable for the middling sort of people. An early tenant was John Neate, a wealthy Bristol merchant, who lived there in 1769 before he built Middlehill House nearby. We see the nature of this Georgian rank of minor aristocracy when in 1775 John advertised for the return of his black slave, John Camery, run away from his service, describing him as of dark complexion, about thirty years of age, stoops in his walk. He described poor John Camery as always bred up in the husbandry business, in other words, a farm worker, implying that John was illiterate and merely a labourer.[10]

Cheney Court was let out on short-term leases; sometimes to people who sought Bath society balls and events to find marriage partners, as Jane Austen portrayed Catherine Moreland in Northanger Abbey; sometimes to take the waters to cure illness. We get some idea of this rapid turnaround when the house was let in 1851 to architect George Manners from Bath, in 1861 to Charles Holworthy and his family, in 1871 to Emily Bonner and in 1881 to Robert George Tufnell.

Some of these tenants became well-known. For a number of years, the Holworthy family dominated society in Box and were some of the wealthiest residents. Charles (1806-1885) appears to be related to Ann Holworthy (1801-) who lived at Newton House, Box, (later called Shrub Hill House, now Heleigh House). Her daughter Elizabeth married Dr Joseph Nash and lived at Ashley House whilst her husband was the owner and resident physician at Kingsdown House. In 1851 Anne Holworthy gave £100 (£14,000 in today’s values) to support 6 old persons of the parish and of the Church of England. It mirrored a gift of £300 (£38,000 today) in 1844 by John Neate of Middlehill to support 10 old men and 10 old women parishioners.

Robert George Tufnell was a retired naval captain who also moved to Shrub Hill House. His claim to fame came through his daughter Jean, a lady-in-waiting to the Queen Mother, widow of George V. In 1897 Jean married the president of the Canadian Pacific Railway who was ennobled as Lord Mount Stephen and she retained the friendship of the Queen Mother who was with her at her death in 1933.[11]

A curious architectural anomaly of the present house built by George Speke in the 1620s is that part of the fabulous appearance is a sham.[4] The windows on the left are staggered to provide light in the staircase, but the windows on the right are false, matching the left but without a staircase behind. The Royal Commission on Historic Monuments described the house as: a provincial builder’s attempt to build a house to the compact, rectangular double-pile plan that was becoming increasingly widespread during the 17th century but whose acceptance throughout the country was affected by the strength of existing building traditions.

Royal Mystery

The contemporary writer, John Aubrey, asserted in the late 1600s that: There is a tradition that (Cheney) Court, which is large and surrounded by a high wall, was used for some military purpose in the Civil Wars.[5] This unproven comment has usually been explained as gossip but there are numerous assertions that the Speke family were Catholic sympathisers at a time when Protestantism was in the ascendancy in England.

In 1644 during the English civil war, it was reported that Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I, hid in a barn at the Court as she fled from Oxford to Exeter on her way to seek refuge in France. Based on the diary of Sir William Dugdale on 17 April 1644, the story goes that The Queen went out of Oxford towards Exeter. The King went with her to Abingdon where she lay the night. It was not safe for her to stay in Oxford, where King Charles was preparing for battle against the Roundheads, and she fled west. When they parted at Abingdon, they would never see each other again, before Charles’ trial in parliament and his execution in 1649. There is no direct mention of Cheney Court in any of the documents.[6]

Nonetheless the legend persists and has grown over time. The Bath Chronicle of 1910 recorded: A peculiarity of the entrance hall is that on the left is a raised dais, which it is supposed was erected for the Queen (Henrietta Maria), the lower part of the Hall being used by the Royal retinue.[7] In 1928 the owner, George Edward Northey, added to the story that the dining room was previously a chapel with a small hole (a leper’s squint) through which offerings could be made to a Catholic priest and the Eucharist received without seeing the priest’s face.[8]

Letting Cheney Court

Dame Anne Speke, widow of Sir Hugh Speke, probably lived here from 1672 until her death in 1686 but after the Speke family sold their estate to the Northeys about 1726, the house was largely used as an investment property for over a century.[9] The Northeys had large landed interests including Woodcote House, Epsom, Surrey and a property at Compton Bassett. For a long time, they let out Cheney Court as a desirable house convenient to Bath, suitable for the middling sort of people. An early tenant was John Neate, a wealthy Bristol merchant, who lived there in 1769 before he built Middlehill House nearby. We see the nature of this Georgian rank of minor aristocracy when in 1775 John advertised for the return of his black slave, John Camery, run away from his service, describing him as of dark complexion, about thirty years of age, stoops in his walk. He described poor John Camery as always bred up in the husbandry business, in other words, a farm worker, implying that John was illiterate and merely a labourer.[10]

Cheney Court was let out on short-term leases; sometimes to people who sought Bath society balls and events to find marriage partners, as Jane Austen portrayed Catherine Moreland in Northanger Abbey; sometimes to take the waters to cure illness. We get some idea of this rapid turnaround when the house was let in 1851 to architect George Manners from Bath, in 1861 to Charles Holworthy and his family, in 1871 to Emily Bonner and in 1881 to Robert George Tufnell.

Some of these tenants became well-known. For a number of years, the Holworthy family dominated society in Box and were some of the wealthiest residents. Charles (1806-1885) appears to be related to Ann Holworthy (1801-) who lived at Newton House, Box, (later called Shrub Hill House, now Heleigh House). Her daughter Elizabeth married Dr Joseph Nash and lived at Ashley House whilst her husband was the owner and resident physician at Kingsdown House. In 1851 Anne Holworthy gave £100 (£14,000 in today’s values) to support 6 old persons of the parish and of the Church of England. It mirrored a gift of £300 (£38,000 today) in 1844 by John Neate of Middlehill to support 10 old men and 10 old women parishioners.

Robert George Tufnell was a retired naval captain who also moved to Shrub Hill House. His claim to fame came through his daughter Jean, a lady-in-waiting to the Queen Mother, widow of George V. In 1897 Jean married the president of the Canadian Pacific Railway who was ennobled as Lord Mount Stephen and she retained the friendship of the Queen Mother who was with her at her death in 1933.[11]

Restoring the Court

We might imagine that after renting out the house for so long, considerable improvements were needed when George Edward Northey decided to live in the house as his main residence in about 1891.[12] We don’t know what work was needed but we might imagine it was the installation of electricity, internal plumbing, bathrooms and kitchen improvements. You have to extend sympathy to George Edward Northey in his attempt to take the mantle of lord of the manor of Box on the death of his father George Wilbraham in 1906. They were very different people with the father feeling he was entitled to spend freely as the lord at the end of his life and the son, an administrator by nature, wanting to get the estate back into solvency.

Their houses reflected this personality difference. George Edward had married Mabel Hunter in 1885 and they had three children, two sons and a daughter who were aged 9 to 19 years. They lived in the 18-roomed Cheney Court together with a handful of servants (sometimes four domestic maids and a couple of personal maids). The house was very much quieter than his father’s house at Ashley Manor, which was the centre of Box life for George Edward’s 12 siblings, their partners, their grandchildren and 7 in-house servants, who regularly assembled at Ashley for Christmas, birthdays and parties.

We might imagine that after renting out the house for so long, considerable improvements were needed when George Edward Northey decided to live in the house as his main residence in about 1891.[12] We don’t know what work was needed but we might imagine it was the installation of electricity, internal plumbing, bathrooms and kitchen improvements. You have to extend sympathy to George Edward Northey in his attempt to take the mantle of lord of the manor of Box on the death of his father George Wilbraham in 1906. They were very different people with the father feeling he was entitled to spend freely as the lord at the end of his life and the son, an administrator by nature, wanting to get the estate back into solvency.

Their houses reflected this personality difference. George Edward had married Mabel Hunter in 1885 and they had three children, two sons and a daughter who were aged 9 to 19 years. They lived in the 18-roomed Cheney Court together with a handful of servants (sometimes four domestic maids and a couple of personal maids). The house was very much quieter than his father’s house at Ashley Manor, which was the centre of Box life for George Edward’s 12 siblings, their partners, their grandchildren and 7 in-house servants, who regularly assembled at Ashley for Christmas, birthdays and parties.

|

It must have been difficult to instil life and activity into Cheney Court and George Edward and Mabel invited friends to fill the void, especially the Deane family of Louisa Fourdrinier, who had married the Rev John Bathurst Dean, master at Merchant Taylors’ School, City of London and rector of St Martins Outwick, Bishopsgate, London.

The family had plenty of interest to introduce, Rev John had been born at the Cape of Good Hope, had written about the Civil War and his ancestors, of the cult of serpent worship when serving in Calcutta, funeral barrows in pre-Christian times, and probably stories about his fifteen children. His second wife Louisa was a Huguenot and related to Cardinal Newman, leader of the high church, Oxford movement. Two of the children are worth mentioning in connection with Cheney Court, Mary (1845-1940) and Eleanor (1851-1941). Mary Deane was a distinguished author and poet of the age and published twelve different volumes. Eleanor was the mother of Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (usually called PG Wodehouse), creator of the Bertie Wooster and Jeeves novels. It is usually believed that Bertie’s aunt Agatha (the one who kills rats with her teeth and devours her young) was modelled on Mary.[13] Left: George Edward Northey and family on the steps of the Court (courtesy Diana Northey) |

Modern Times at Cheney Court

In the inter-war years, the Japanese garden was one of the features of the Court with the lake hidden by water lilies and a cascading stream extending through a rapidly-sloping grotto which extends down the valley.[14] But the upkeep was massive and the facilities in need of modernising. After George Edward’s death in 1932, Mabel sold various pieces of furniture in 1933 and the house was left vacant until Armand Northey moved there in 1935.[15] By the end of the Second World War Armand Northey decided to sell Cheney Court in 1948, along with his other Ditteridge properties. For a while the house was used as an hotel and restaurant. The oldest remaining part of the current house is believed to be the single-storey section which used to be the farmhouse, later the ballroom at the hotel, and now individual classrooms.

Bath Spa Factors started in the 1930s servicing expensive cars and grew into a European network selling motor car accessories. In 1979 Frank William Norman who owned Spafax started an international television and marketing company based at Cheney Court and Box Mill. The smaller and older barn was pulled down but a larger one was used as a television studio. It is a fabulous Grade II building, quoted by the listing as possibly early 17th century, similar to the house.[16] Local builder Stan Scarth did all the maintenance and laid the cobbled car park outside the barn, which won a National Trust award.

In the inter-war years, the Japanese garden was one of the features of the Court with the lake hidden by water lilies and a cascading stream extending through a rapidly-sloping grotto which extends down the valley.[14] But the upkeep was massive and the facilities in need of modernising. After George Edward’s death in 1932, Mabel sold various pieces of furniture in 1933 and the house was left vacant until Armand Northey moved there in 1935.[15] By the end of the Second World War Armand Northey decided to sell Cheney Court in 1948, along with his other Ditteridge properties. For a while the house was used as an hotel and restaurant. The oldest remaining part of the current house is believed to be the single-storey section which used to be the farmhouse, later the ballroom at the hotel, and now individual classrooms.

Bath Spa Factors started in the 1930s servicing expensive cars and grew into a European network selling motor car accessories. In 1979 Frank William Norman who owned Spafax started an international television and marketing company based at Cheney Court and Box Mill. The smaller and older barn was pulled down but a larger one was used as a television studio. It is a fabulous Grade II building, quoted by the listing as possibly early 17th century, similar to the house.[16] Local builder Stan Scarth did all the maintenance and laid the cobbled car park outside the barn, which won a National Trust award.

Linguarama opened Cheney Court in April 1989 as its flagship residential language school, which it continues to be today. Later, the entrepreneur Marcus Evans acquired the company and it became part of his international sports and marketing group. The Cheney Court site is the British base for the group’s international language, on-line training school. It is curious that, compared to the local estate of the Speke and Northey families, many in the world now know of Box village through its worldwide language school and sometimes visit on the residential courses they run in Ditteridge.

As we can see from the Victorian photographs above, it was the dense foliage on the exterior of the building that gave it a sense of Gothic mystery. Without this facade the building is now elegant, proportional and welcoming.

Appendix: Early History of the Court

The manor of Ditteridge was reputedly held by Richard Pembridge in 1375, then John Blant of Button in 1444 and Edward Stafford in 1455 who left one part of the estate to the Paveley family of Westbury. The area was inherited via a Paveley marriage to Ralph Cheney and passed to Sir Edmund Cheney in 1431, then to John Cheney in 1478.[17] The latter was active in Wars of Roses, a Lancastrian who opposed Henry VI and supported Edward IV, ending as Master of Horse. In 1483 John Cheney and Walter Hungerford led rebellion against Richard III but went into exile with Henry Tudor when it failed. He was knighted by Henry Tudor and became baron in 1487. Later owner, George Edward Northey, believed that the house was built in 1493, a few years before John Cheney died without heir in 1499 and was buried in Salisbury Cathedral.[18]

The manor of Ditteridge was reputedly held by Richard Pembridge in 1375, then John Blant of Button in 1444 and Edward Stafford in 1455 who left one part of the estate to the Paveley family of Westbury. The area was inherited via a Paveley marriage to Ralph Cheney and passed to Sir Edmund Cheney in 1431, then to John Cheney in 1478.[17] The latter was active in Wars of Roses, a Lancastrian who opposed Henry VI and supported Edward IV, ending as Master of Horse. In 1483 John Cheney and Walter Hungerford led rebellion against Richard III but went into exile with Henry Tudor when it failed. He was knighted by Henry Tudor and became baron in 1487. Later owner, George Edward Northey, believed that the house was built in 1493, a few years before John Cheney died without heir in 1499 and was buried in Salisbury Cathedral.[18]

The Court and the barn are shown prominently on the Allen map of 1626 (above). The chimneys on the house resemble the current layout but artistic licence has been taken with the number of windows. (Courtesy Wilts History Centre)

After the Speke family bought extensive land in Box in the early 1600s, the eldest son George Speke (1598-1656) married Margaret Tempest and he appears to have rebuilt the house.[19] The changes included the Speke-Tempest coat-of-arms above an exterior door and over a stone fireplace flanked by cherubs and cornucopias with festoons each side, lion masks over and top modillion cornice.[20] In his will of 1656, George Speke described himself as from Ditteridge, presumably meaning that he still lived at Cheney Court.[21]

After the Speke family bought extensive land in Box in the early 1600s, the eldest son George Speke (1598-1656) married Margaret Tempest and he appears to have rebuilt the house.[19] The changes included the Speke-Tempest coat-of-arms above an exterior door and over a stone fireplace flanked by cherubs and cornucopias with festoons each side, lion masks over and top modillion cornice.[20] In his will of 1656, George Speke described himself as from Ditteridge, presumably meaning that he still lived at Cheney Court.[21]

Occupants of Cheney Court in Census Records

1841: residents not found

1851: George P Manners (1789-) architect; wife Elizabeth (1805-); and four children at school Isabella (1839-); Sarah (1840-); George M (1842-); Elizabeth D (1845-); two servants and one visitor.

1861: Charles Holworthy (1806-1885); three children living on private means - Charles W (1836-); Frederick (1838-); and Constance M (1840-); son John (1842-) mariner; and two daughters at school Letitia (1844-); and Beata H (1851-); together with four servants, cook, housemaid, housekeeper and gardener; and two female visitors from Middlesex.

1871: Emily Bonner (1829-), widow; her son John Hamlyn Bonner (1850-) Oxford undergraduate; and two servants, a parlourmaid and cook.

1881: Robert Tufnell (1825-), widower and retired Royal Navy captain; daughter Georgina (1863-); and Robert’s brother Arthur (1836-), retired colonel of the 60th Rifles.

1891: Louisa Deane (1811-), widow; daughter Mary Dean (1845-) authoress; daughter Eleanor Wodehouse (1851-); and two servants parlourmaid and cook.

1901: Louisa Deane (1811-), widow; daughter Mary Dean (1845-) authoress;

1911: The only people occupying the 18 rooms there were four servants Alice Powell (domestic nurse), age 42; Margaret Wilson (cook), age 35; Laura Mills (parlour maid), 30; and Rose Wicks (house maid), 17.

1939: Armand Hunter Kennedy Wilbraham-Northey (16 January 1897-); wife Millie (1909-), cook, housemaid and between-maid. He was knighted at Buckingham Palace in 1958.

1841: residents not found

1851: George P Manners (1789-) architect; wife Elizabeth (1805-); and four children at school Isabella (1839-); Sarah (1840-); George M (1842-); Elizabeth D (1845-); two servants and one visitor.

1861: Charles Holworthy (1806-1885); three children living on private means - Charles W (1836-); Frederick (1838-); and Constance M (1840-); son John (1842-) mariner; and two daughters at school Letitia (1844-); and Beata H (1851-); together with four servants, cook, housemaid, housekeeper and gardener; and two female visitors from Middlesex.

1871: Emily Bonner (1829-), widow; her son John Hamlyn Bonner (1850-) Oxford undergraduate; and two servants, a parlourmaid and cook.

1881: Robert Tufnell (1825-), widower and retired Royal Navy captain; daughter Georgina (1863-); and Robert’s brother Arthur (1836-), retired colonel of the 60th Rifles.

1891: Louisa Deane (1811-), widow; daughter Mary Dean (1845-) authoress; daughter Eleanor Wodehouse (1851-); and two servants parlourmaid and cook.

1901: Louisa Deane (1811-), widow; daughter Mary Dean (1845-) authoress;

1911: The only people occupying the 18 rooms there were four servants Alice Powell (domestic nurse), age 42; Margaret Wilson (cook), age 35; Laura Mills (parlour maid), 30; and Rose Wicks (house maid), 17.

1939: Armand Hunter Kennedy Wilbraham-Northey (16 January 1897-); wife Millie (1909-), cook, housemaid and between-maid. He was knighted at Buckingham Palace in 1958.

References

[1] The Historic Buildings Listing of the house suggests that part of the early house still exists on the lower floor on east side probably 1500s with moulded elliptical arched north and fireplace rind arched recesses.

[2] The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine 1930, Volume 45 and RB Pugh (editor), The Victoria History of the Counties of England: A History of Wiltshire, 1957

[3] Richard Hodges, www.archaeology.co.uk, April 2013, p.42

[4] The Royal Commission on Historic Monuments, 1992

[5] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, p.59

[6] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 28 April 1923

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[8] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 22 September 1928

[9] GJ Kidston: A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.239

[10] The Bath Chronicle, 27 July 1775

[11] The Daily Mirror, 2 May 1933

[12] In 1891 George Edward, his family and servants were recorded in the census as living at Myrtle Cottage, Ashley, presumably while the Cheney Court was being renovated.

[13] PG Wodehouse, Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, chapter 1

[14] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 22 September 1928

[15] The Wiltshire Times, 28 January 1933 and 18 May 1935

[16] See Historic Buildings Listing

[17] Ken Watts, The Wiltshire Cotswolds, 2007, The Hobnob Press, p.174-76

[18] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 22 September 1928

[19] GJ Kidston: A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.198

[20] See Historic Buildings Listing

[21] GJ Kidston: A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.235

[1] The Historic Buildings Listing of the house suggests that part of the early house still exists on the lower floor on east side probably 1500s with moulded elliptical arched north and fireplace rind arched recesses.

[2] The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine 1930, Volume 45 and RB Pugh (editor), The Victoria History of the Counties of England: A History of Wiltshire, 1957

[3] Richard Hodges, www.archaeology.co.uk, April 2013, p.42

[4] The Royal Commission on Historic Monuments, 1992

[5] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, p.59

[6] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 28 April 1923

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[8] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 22 September 1928

[9] GJ Kidston: A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.239

[10] The Bath Chronicle, 27 July 1775

[11] The Daily Mirror, 2 May 1933

[12] In 1891 George Edward, his family and servants were recorded in the census as living at Myrtle Cottage, Ashley, presumably while the Cheney Court was being renovated.

[13] PG Wodehouse, Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, chapter 1

[14] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 22 September 1928

[15] The Wiltshire Times, 28 January 1933 and 18 May 1935

[16] See Historic Buildings Listing

[17] Ken Watts, The Wiltshire Cotswolds, 2007, The Hobnob Press, p.174-76

[18] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 22 September 1928

[19] GJ Kidston: A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.198

[20] See Historic Buildings Listing

[21] GJ Kidston: A History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.235