Arthur George (Sonny) Currant, Railway Ganger Alan Payne, October 2022

|

We think of the stone mines as providing most of the employment in the village during the late Victorian period through quarrying excavation (miners), pickers (sounding the roof) and stone masons. This is true but there was another influx of people who also became important.

This is the story of just one of the mid-twentieth century workers on the railways, Arthur George Currant., father of Box resident John Currant, who recounts his story. Arthur George (known as Sonny) Currant My father Arthur George Currant was a railwayman for most of his life. He was born at Wilton Cottages, Ashley on 13 September 1905 and died at 7 Bargates, Box on 19 February 1973. On 16 January 1943, he married my mother Olive Jones, who was born near Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, into a Welsh-speaking family. Olive suffered tuberculosis as a child and went into a sanatorium in Wales, Craig-Y-Nos Castle, which had been the former home of the famous Italian opera singer, Adelina Patti. Olive first came to the village in 1940 to work as a nurse at the Kingsdown Lunatic Asylum. My father met her off the train and offered to carry her bags and that was the beginning of their relationship and in 1943 their marriage at Llanelli. After marriage they lived at 12 Lowden, Chippenham and Arthur cycled to Box every day to work at Box Station. |

My father always took lunch with him at work, together with a glass bottle full of milky tea. When he came home to Lowden he would often go to the The Plough pub. Whenever I asked where he was going, he would say to see aman about a dog. We never got a dog! They eventually moved back to Box in 1953.

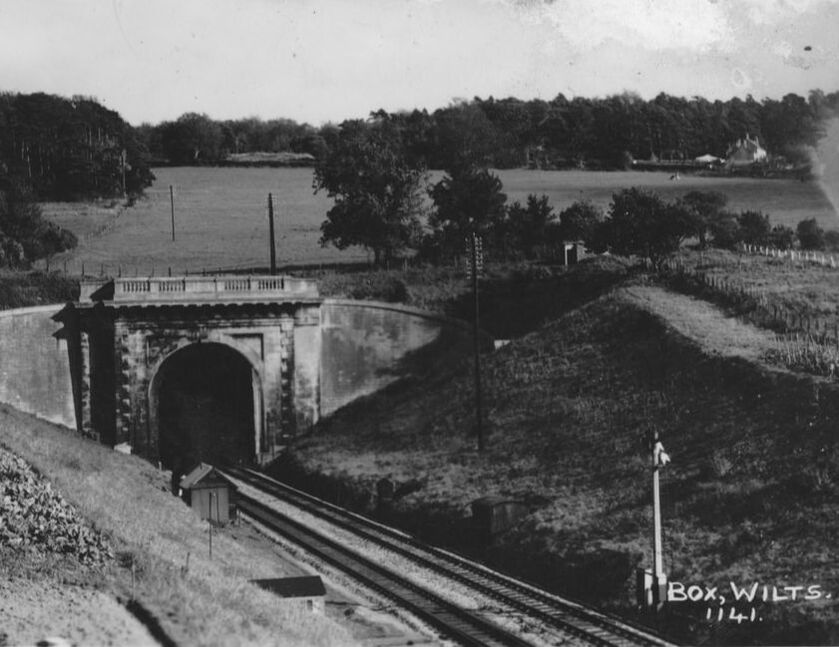

Once familiar sights in the centre of Box with frequent locomotives passing Box Bridge (courtesy John Currant)

Arthur's Length (as he called it) of railway line was from Shockerwick Bridge to the middle of Box Tunnel. He always rebutted the story of seeing the sun rise through Box Tunnel on Brunel's birthday as the Tunnel was constantly full of smoke. The Tunnel itself looked very different in the period after the Second World War without trees lining the banks because the gang were responsible for hand-scything the undergrowth to prevent the possibility of engines catching the sides alight from fire sparks. For their part the GWR was a good employer and dad attended various Permanent Way Education Classes and was awarded several certificates.

Dad was involved in a tragic railway accident when one of his colleagues, Jeremiah Daly, was killed at work. Jerry, who is possibly seen in photograph below, was 42 years old and lived at 2 Pleasant View, Kingsdown.[1] Arthur gave evidence to the inquest that Mr Daly was a look-out man for his gang who was in the tunnel and blew his whistle to give the other workers warning of the approaching train. Jeremiah was caught by the train and a newly-lit cigarette was (found, still) leaning against the wall.

It wasn't only Box Tunnel that was a problem because bad weather was also dangerous for trackside workers. It was customary to have a lookout man stationed on bends in the line whose task was to blow a foghorn to warn of oncoming traffic and, in serious bad weather, detonators were put on the line which exploded to give a warning when a train passed over them. This sort of protection was vital because, in order to get to the part of the rail needing repair, the workers would travel on a hand pump trolley and prior notice had to be given to stop main line trains coming through on the workers' route to the repair point.

Dad was involved in a tragic railway accident when one of his colleagues, Jeremiah Daly, was killed at work. Jerry, who is possibly seen in photograph below, was 42 years old and lived at 2 Pleasant View, Kingsdown.[1] Arthur gave evidence to the inquest that Mr Daly was a look-out man for his gang who was in the tunnel and blew his whistle to give the other workers warning of the approaching train. Jeremiah was caught by the train and a newly-lit cigarette was (found, still) leaning against the wall.

It wasn't only Box Tunnel that was a problem because bad weather was also dangerous for trackside workers. It was customary to have a lookout man stationed on bends in the line whose task was to blow a foghorn to warn of oncoming traffic and, in serious bad weather, detonators were put on the line which exploded to give a warning when a train passed over them. This sort of protection was vital because, in order to get to the part of the rail needing repair, the workers would travel on a hand pump trolley and prior notice had to be given to stop main line trains coming through on the workers' route to the repair point.

|

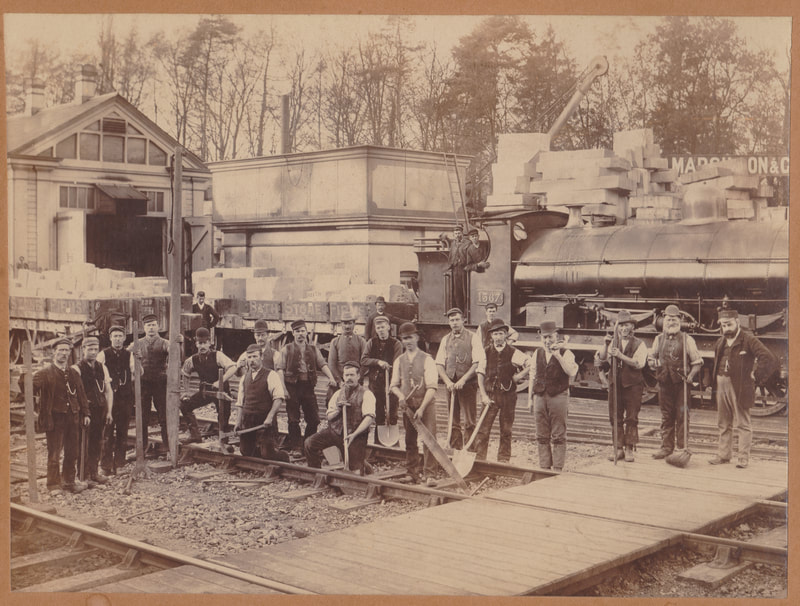

As a completely new industry, the railways had to develop new words to describe the work of employees. Two such terms were platelayers and gangers. Platelayers was an early word for the men who laid the original rails for Welsh coal tramways. The plates were flatter than modern rails, roughly in the shape of an L and without the usual edging, a design which was not needed until flanged wheels were developed to enable the railroads to carry heavier wagons. The name platelayers stuck for later rail engineers. Gangers were the foremen in charge of a group of platelayers but they also had a specific responsibility for the maintenance of an identified section of the permanent way on a railway. The gangers were responsible for the inspection, repair and overall supervision of their length of track and were sometimes referred to as lengthmen.[2] When needed, the lengthman would be allocated to a couple of miles of track, with a hut at the side of the line where he could keep his equipment and from where he could monitor his length of line. Left: Gangers at Box: Left to Right Front Row: Frank Codger Smith, Bill Robbins, M Hill. Back Row Arthur George Currant (half-hidden) and possibly Jerry Daly (courtesy John Currant) |

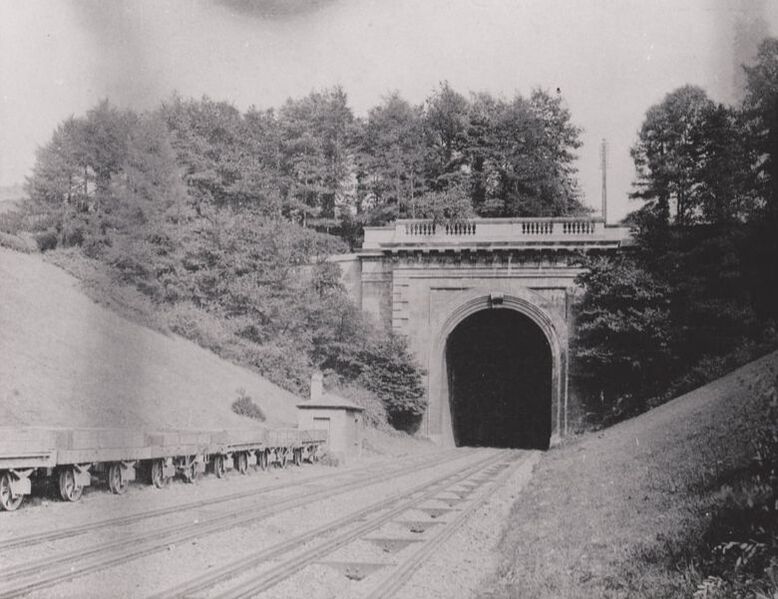

Arthur's shed for his Gang outside Box Tunnel (courtesy Rose Ledbury and John Currant via Gordon Hall)

Ganger Codes of Practice

There was a lot more than rail maintenance for the gangers to monitor. After the war British Railways issued a guidance booklet of the codes of practice for them to consider.[3] It was full of practical advice: Water is the worst enemy of a good track. It is therefore necessary to see that the permanent way drains are kept in good working order... Some streams are apt to change their course. Gangers should therefore watch those which are likely to do so. There was considerable information about the undergrowth: Grass on slopes should be cut or burnt before grass seeds ripen and scatter. (Grass stacks) should be burnt while standing the cut swarth at the top and bottom of the slop and carefully raked back to the standing grass to prevent the fire spreading. And so it went on dealing with trees, hedges, hoardings, rock cuttings, roadways as well as instructions about the track itself, ballast and sleepers.

The gangers kept a variety of tools and equipment in the trackside sheds for this type of work as well as replacement parts for small repair jobs. The sheds also served as gathering points for lunchtimes and clothing stores for variable weather. I remember my father and his gang cooking snails for their lunch in a bucket over a small fire outside the Box Tunnel shed.

There was a lot more than rail maintenance for the gangers to monitor. After the war British Railways issued a guidance booklet of the codes of practice for them to consider.[3] It was full of practical advice: Water is the worst enemy of a good track. It is therefore necessary to see that the permanent way drains are kept in good working order... Some streams are apt to change their course. Gangers should therefore watch those which are likely to do so. There was considerable information about the undergrowth: Grass on slopes should be cut or burnt before grass seeds ripen and scatter. (Grass stacks) should be burnt while standing the cut swarth at the top and bottom of the slop and carefully raked back to the standing grass to prevent the fire spreading. And so it went on dealing with trees, hedges, hoardings, rock cuttings, roadways as well as instructions about the track itself, ballast and sleepers.

The gangers kept a variety of tools and equipment in the trackside sheds for this type of work as well as replacement parts for small repair jobs. The sheds also served as gathering points for lunchtimes and clothing stores for variable weather. I remember my father and his gang cooking snails for their lunch in a bucket over a small fire outside the Box Tunnel shed.

When Bill Hemmings died whilst working as steward of The Comrades Club, my parents took over and in 1958 moved into the premises (now called Hardy House). Dad was still employed on maintenance of Box Tunnel until he was made redundant in 1966 following cost-savings by Dr Beeching. The connection with the railway was ingrained in the family culture and Dad bought the signal box shed when it was no longer needed. After his redundancy from GWR, he worked at Moon Aircraft Company at Clift Quarry Works, Box Hill. There he made Bakelite trays used on aircraft to serve meals but their business gradually declined. He also did gardening work for locals including Cecil Lambert in The Ley. He enjoyed scything orchards and we were never short of apples to eat.

Conclusion

When Box Station and Mill Lane Halt were closed in 1964, it wasn’t just transport facilities that went but also considerable employment for local people. The railway infrastructure was reduced in a general distrust of nationalised industries but skilled, well-paid jobs were also lost together with proper benefits offered by the railway companies, such as pensions and life insurance. It affected many generations of people because work on the railways had seemed to be secure and many children had followed their parents into the industry.

Conclusion

When Box Station and Mill Lane Halt were closed in 1964, it wasn’t just transport facilities that went but also considerable employment for local people. The railway infrastructure was reduced in a general distrust of nationalised industries but skilled, well-paid jobs were also lost together with proper benefits offered by the railway companies, such as pensions and life insurance. It affected many generations of people because work on the railways had seemed to be secure and many children had followed their parents into the industry.

References

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 1 May 1954

[2] Courtesy The Platelayers Society

[3] Codes of Practice for Gangers, Sub-gangers and lengthmen, British Rail, April 1952

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 1 May 1954

[2] Courtesy The Platelayers Society

[3] Codes of Practice for Gangers, Sub-gangers and lengthmen, British Rail, April 1952