Buildings of Kingsdown House Asylum Dr Peter Carpenter October 2022

The buildings at the house evolved over the years to fit the needs of the time. Bristol psychiatrist Dr Peter Carpenter has researched the early story of the property, previously unrecorded, and explains how the houses were built and demolished.

In 1814 Charles Langworthy told a visitor that Kingsdown House had been an asylum for 200 years but the evidence for his claim is not given.[1] Given he had made his money promoting the fraudulent Perkinean Tractors to cure all aches and pains, he probably is not a reliable witness. However, the facility is still probably the oldest, long-running, provincial asylum in England.

The Box Madhouse or Asylum appears in a published Quaker pamphlet in 1697 and the Quaker records record an asylum in the area in 1684. What we do not know is where it was first located, if not Kingsdown House, and who first ran it if not the Jeffreys, although we can identify Kingsdown House as the site by 1750.

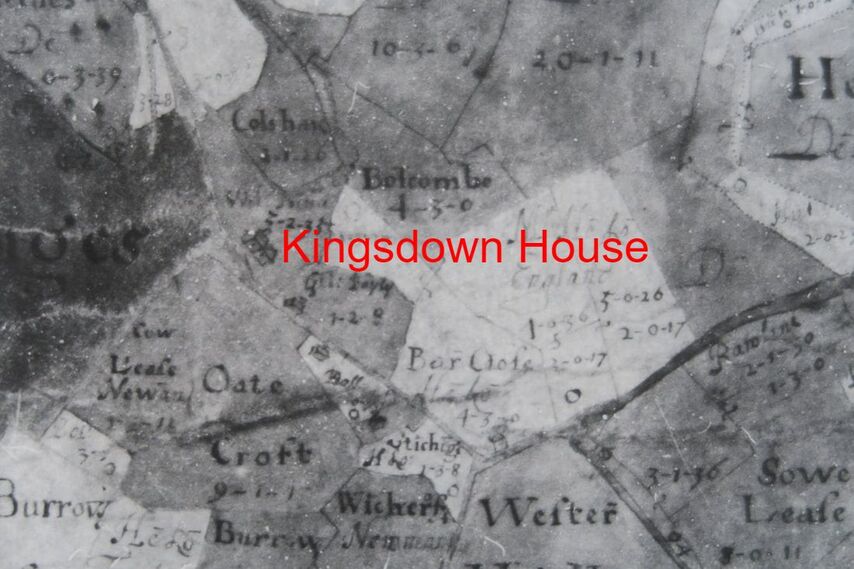

Allen’s 1626 map of the Speke estate in Box appears to show Kingsdown House, at the bend of Doctor’s Hill, labelled as tenanted by the Widow Newman. The area seems to be in a state of change because a later map by Francis Allen in 1630, omits any reference to her. There is a woman called Sibyl Newman recorded as buried in Box on 22 February 1626 (not stated to be a widow or where she lived) who may be the relevant person. There is no indication of the use of the house, which is shown as a single property.

The Box Madhouse or Asylum appears in a published Quaker pamphlet in 1697 and the Quaker records record an asylum in the area in 1684. What we do not know is where it was first located, if not Kingsdown House, and who first ran it if not the Jeffreys, although we can identify Kingsdown House as the site by 1750.

Allen’s 1626 map of the Speke estate in Box appears to show Kingsdown House, at the bend of Doctor’s Hill, labelled as tenanted by the Widow Newman. The area seems to be in a state of change because a later map by Francis Allen in 1630, omits any reference to her. There is a woman called Sibyl Newman recorded as buried in Box on 22 February 1626 (not stated to be a widow or where she lived) who may be the relevant person. There is no indication of the use of the house, which is shown as a single property.

Above: Allen’s 1626 map of Kingsdown and Below: the 1630 map shows a double house (both courtesy Wilts History Centre)

Kingsdown House and the Harris family

In 1638, James Harris recorded in his will that he lived in Kingsdown House. James Harris gave Kingsdown House to his eldest son, 8-year-old Zachariah Harris. The inventory to James’ will described a medieval property with a hall, a bed chamber above the hall and another above the entry, and a little chamber holding wool. There is no mention of an excessive number of beds for patients or of irons, restraints or other items referring to the means then used to manage madness. The assets listed were

33 sheep and a heifer and weaning calf, possibly animals for domestic use (or just a hobby), and lacking husbandry implements or breeding stock to indicate commercial farming.

After his death James Harris’ widow Bridget continued to live there and raised four children but we don’t know how she made her living after his death. One child, Zachariah Harris, married Jone (sic) and they had two sons and a daughter (another Jone). Both sons died young leaving Jone as the sole heir. In 1681 she married Edward Jeffery, a 36-year-old farmer and they all stayed at Kingsdown House until Jone Harris’ death in 1689 and Zachariah’s demise in 1694. Thus, Kingsdown House entered the Jeffreys family.

Local lore says that the original Kingsdown House and asylum building was the garages (below). It has two storeys and is unique on the site in having rough stone walls and stone tiles. But we have no evidence for this, other than it may have been a very suitable site for the original buildings, set back from the road but the building next to it, which also has stone tiled roof, may be as old.

In 1638, James Harris recorded in his will that he lived in Kingsdown House. James Harris gave Kingsdown House to his eldest son, 8-year-old Zachariah Harris. The inventory to James’ will described a medieval property with a hall, a bed chamber above the hall and another above the entry, and a little chamber holding wool. There is no mention of an excessive number of beds for patients or of irons, restraints or other items referring to the means then used to manage madness. The assets listed were

33 sheep and a heifer and weaning calf, possibly animals for domestic use (or just a hobby), and lacking husbandry implements or breeding stock to indicate commercial farming.

After his death James Harris’ widow Bridget continued to live there and raised four children but we don’t know how she made her living after his death. One child, Zachariah Harris, married Jone (sic) and they had two sons and a daughter (another Jone). Both sons died young leaving Jone as the sole heir. In 1681 she married Edward Jeffery, a 36-year-old farmer and they all stayed at Kingsdown House until Jone Harris’ death in 1689 and Zachariah’s demise in 1694. Thus, Kingsdown House entered the Jeffreys family.

Local lore says that the original Kingsdown House and asylum building was the garages (below). It has two storeys and is unique on the site in having rough stone walls and stone tiles. But we have no evidence for this, other than it may have been a very suitable site for the original buildings, set back from the road but the building next to it, which also has stone tiled roof, may be as old.

An asylum was operating at Kingsdown House in 1749 but there is evidence from the Bristol Quaker records suggesting that an asylum existed in Box in 1687, perhaps connected with another asylum at Batheaston or mistakenly thought to be in Batheaston.

Ann Hill, a Quaker woman in her 60s, was needing care and the meeting agreed to move her to Box:Beneaston (presumably Batheaston) or where else they shall find meet and the charge to be borne by this meeting.[2] The Batheaston home was also used in 1674 for a young man with distracted destemper. (a term used for insanity).[3] In 1696 there are various references in a book written by Benjamin Coole entitled The Quakers cleared from being Apostates or the Hammerer defeated, and proved an Imposter, which states:

The Quakers practice in the last Suffering Times, abundantly proved their Unanimity; and whoever is Ignorant of it, must have lived farther off than Moorfields* or Box either, unless Infants, Deaf, Dumb or Idiots: (*Bedlam, and Box, Places for the Cure of Mad People).[4] There are other references also, such as in 1729 when the son of Mr Coleman, having run distracted for the Unkindness of his Sweetheart, so as to be corded down in his Bed…. The young Man is since convey’d to Box Madhouse.[5]

We do know that Edward Jeffreys lived in Kingsdown House in 1694 when he inherited it (probably just the lease of the house) from his father-in-law Zachariah Harris. In 1695 Edward paid 5d rates on a property and Edward lived on until 1706. Even then, his widow Jone, continued to live there with her children.

Ann Hill, a Quaker woman in her 60s, was needing care and the meeting agreed to move her to Box:Beneaston (presumably Batheaston) or where else they shall find meet and the charge to be borne by this meeting.[2] The Batheaston home was also used in 1674 for a young man with distracted destemper. (a term used for insanity).[3] In 1696 there are various references in a book written by Benjamin Coole entitled The Quakers cleared from being Apostates or the Hammerer defeated, and proved an Imposter, which states:

The Quakers practice in the last Suffering Times, abundantly proved their Unanimity; and whoever is Ignorant of it, must have lived farther off than Moorfields* or Box either, unless Infants, Deaf, Dumb or Idiots: (*Bedlam, and Box, Places for the Cure of Mad People).[4] There are other references also, such as in 1729 when the son of Mr Coleman, having run distracted for the Unkindness of his Sweetheart, so as to be corded down in his Bed…. The young Man is since convey’d to Box Madhouse.[5]

We do know that Edward Jeffreys lived in Kingsdown House in 1694 when he inherited it (probably just the lease of the house) from his father-in-law Zachariah Harris. In 1695 Edward paid 5d rates on a property and Edward lived on until 1706. Even then, his widow Jone, continued to live there with her children.

Developing the Property

We begin to see Kingsdown House and probably its asylum developing after November 1729 when William Northey of Compton Bassett sold the freehold for Kingsdown House to James Jefferys, Practitioner in Physick.[6] Northey sold the freehold of the nearby Cottages, and site of Prospect House to James’ brother William in 1732.

Possession of the property encouraged the Jeffreys family to develop the estate at Kingsdown House. Number 1, the prestigious property with a clock, is stylistically dated to the early 1700s by Historic England, and it appears to reflect the importance of the new owners.

The window tax of 1696 didn’t stop the owners of the new house from demonstrating their wealth with arrays of windows on the facia of number 1. In the window tax records of 1754, James Jefferys paid tax for 17 windows for his house and 9 windows for the old house. We can assume that the newer house was number 1, Kingsdown House and the number of windows seems to fit the original building, but there is no indication of the location of the old house. It wasn’t modern number 2 because the date of that is asserted to be the early 1800s.

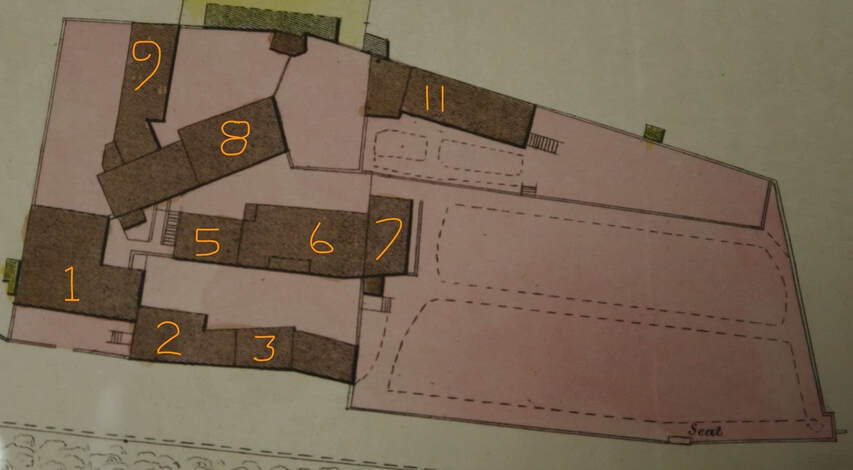

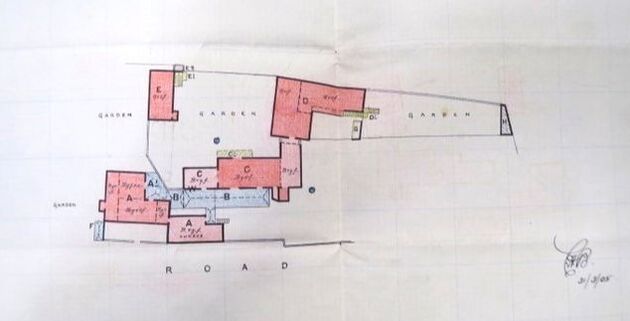

The county register in the National Archives [7] is a register of all private asylum admissions between 1801 and 1812. It appears to be very incomplete but it records 59 admissions at Kingsdown during this time, under the management of Jane Jefferys whilst her daughter was still a minor. The Langworthys took over the asylum in about 1813. In the 1814 visit by Wakefield the asylum is stated to have 40 patients with 9 servants. It is tempting to see the proprietor living in the main house (1 in figure below) with the 40 patients in the converted and purpose-built outhouses, both 5 & 6 and with more in 2 & 3 arranged around a courtyard.

At this time though it would have been expected that the wealthiest patients lived with the master and shared his table.

We begin to see Kingsdown House and probably its asylum developing after November 1729 when William Northey of Compton Bassett sold the freehold for Kingsdown House to James Jefferys, Practitioner in Physick.[6] Northey sold the freehold of the nearby Cottages, and site of Prospect House to James’ brother William in 1732.

Possession of the property encouraged the Jeffreys family to develop the estate at Kingsdown House. Number 1, the prestigious property with a clock, is stylistically dated to the early 1700s by Historic England, and it appears to reflect the importance of the new owners.

The window tax of 1696 didn’t stop the owners of the new house from demonstrating their wealth with arrays of windows on the facia of number 1. In the window tax records of 1754, James Jefferys paid tax for 17 windows for his house and 9 windows for the old house. We can assume that the newer house was number 1, Kingsdown House and the number of windows seems to fit the original building, but there is no indication of the location of the old house. It wasn’t modern number 2 because the date of that is asserted to be the early 1800s.

The county register in the National Archives [7] is a register of all private asylum admissions between 1801 and 1812. It appears to be very incomplete but it records 59 admissions at Kingsdown during this time, under the management of Jane Jefferys whilst her daughter was still a minor. The Langworthys took over the asylum in about 1813. In the 1814 visit by Wakefield the asylum is stated to have 40 patients with 9 servants. It is tempting to see the proprietor living in the main house (1 in figure below) with the 40 patients in the converted and purpose-built outhouses, both 5 & 6 and with more in 2 & 3 arranged around a courtyard.

At this time though it would have been expected that the wealthiest patients lived with the master and shared his table.

Expansion under the Langworthys

Wakefield’s description of the house in 1814 when he was allowed to see only some of the women is not good:

It is delightfully situated, the house and ground commanding cheerful views. There were four women in a small yard. I saw in a place which on one side I must call a cellar, and on the other side it is open to a yard, in which there were four women. In this room or cellar, I saw lying upon straw on fixed bedsteads, two women nearly naked; around their beds there was a deal partition. I heard more in similar places making a great, noise; Dr Langworthy stating that they were perfectly naked, I did not attempt to look at them. The room in which they were confined is entirely dark; and I think in the course of my visiting these places I never recollect to have seen four living persons in so wretched a place.

His description fits with the women being in buildings 5 and 6 which, due to the sloping land, have a basement now used as garages and an entrance on the first floor on the other side into the courtyard. In an 1850 plan it houses women. The men would have been in 2 and 3.

During the early 1800s there was a growth in interest in the inappropriate housing of lunatics in workhouses and prisons.

With the 1834 Poor Law Act, the new Poor Law Unions started to look en masse for places to house them. As few counties had already built public Lunatic Asylums, there was a vast market for entrepreneurs to tap. Private asylums mushroomed around the country.

Charles Langworthy increased the number of patients in his asylum from the 40 in 1814 to 50 or 60 in 1835, so he probably built some new buildings during this time most likely one of the buildings 2 and 6 above. The magistrates’ visits are recorded after 1828 and routinely describe his facilities as clean and satisfactory and in 1830 talk of having inspected the rooms, yards, courts and airing grounds. He took out a loan of £1,500 in 1828 and it is possible that he used this to buy the freehold from the Jeffreys and/or to build part of the complex of buildings 2 to 6. In 1835 Dr Charles Langworthy borrowed £1,000 via a mortgage on the Asylum and probably used this to build extra accommodation for paupers. This was probably 8 and 9 in the plan above – 9 as the female day room and 8 as the female cells with a kitchen between. Number 11 was the male ward and may have been built then or a few years later under pressure to reduce the overcrowding.

He had taken on a contract with Somerset to admit its pauper patients. The next year he admitted 75 patients, and for several years had over 120 patients, most of whom were parish pauper cases. The 1850 plans show Number 8 as a fairly unpleasant set of bedroom cells. The magistrates state in 1837 that the place is suitable for 140 patients and a year later refer to the additional buildings appropriated to the pauper patients being constructed appropriately. They lamented that Charles was ill and no doctor was resident at the asylum. His son Austen was busy running his own asylum at Long Ashton and only visited when possible.

By 1842 when the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy visited, the Asylum routinely held 35 private patients and 100 or more paupers. Their report of 1844 blasted the place, declaring:

Kingsdown House, at Box, near Bath, was first visited in September, 1842. Amongst its great defects, is the want of airing-grounds. The space allowed for exercise, considering the number of Patients, is wholly insufficient. One of the wards, [almost certainly number 8] in which were fifty Female Paupers, had only a very small yard attached to it, and this, being on an abrupt descent and uneven throughout, was not only unfit for exercise, but was insufficient for half the number of Patients; and they were consequently congregated in a small room at one extremity of the yard. Every seat there was occupied, and the room itself being ill-ventilated, there existed an offensive odour that must have been detrimental to the bodily health of the Patients.

The airing courts for the Females is surrounded by very high walls, and is dull and cheerless, and the only yard for the Male Paupers is but little better.

They criticised the excessive use of restraint and the magistrates for not supervising the place better, and later stated that the place was illegal in not having a resident medical doctor (Charles lived at 24 The Circus, Bath).

Wakefield’s description of the house in 1814 when he was allowed to see only some of the women is not good:

It is delightfully situated, the house and ground commanding cheerful views. There were four women in a small yard. I saw in a place which on one side I must call a cellar, and on the other side it is open to a yard, in which there were four women. In this room or cellar, I saw lying upon straw on fixed bedsteads, two women nearly naked; around their beds there was a deal partition. I heard more in similar places making a great, noise; Dr Langworthy stating that they were perfectly naked, I did not attempt to look at them. The room in which they were confined is entirely dark; and I think in the course of my visiting these places I never recollect to have seen four living persons in so wretched a place.

His description fits with the women being in buildings 5 and 6 which, due to the sloping land, have a basement now used as garages and an entrance on the first floor on the other side into the courtyard. In an 1850 plan it houses women. The men would have been in 2 and 3.

During the early 1800s there was a growth in interest in the inappropriate housing of lunatics in workhouses and prisons.

With the 1834 Poor Law Act, the new Poor Law Unions started to look en masse for places to house them. As few counties had already built public Lunatic Asylums, there was a vast market for entrepreneurs to tap. Private asylums mushroomed around the country.

Charles Langworthy increased the number of patients in his asylum from the 40 in 1814 to 50 or 60 in 1835, so he probably built some new buildings during this time most likely one of the buildings 2 and 6 above. The magistrates’ visits are recorded after 1828 and routinely describe his facilities as clean and satisfactory and in 1830 talk of having inspected the rooms, yards, courts and airing grounds. He took out a loan of £1,500 in 1828 and it is possible that he used this to buy the freehold from the Jeffreys and/or to build part of the complex of buildings 2 to 6. In 1835 Dr Charles Langworthy borrowed £1,000 via a mortgage on the Asylum and probably used this to build extra accommodation for paupers. This was probably 8 and 9 in the plan above – 9 as the female day room and 8 as the female cells with a kitchen between. Number 11 was the male ward and may have been built then or a few years later under pressure to reduce the overcrowding.

He had taken on a contract with Somerset to admit its pauper patients. The next year he admitted 75 patients, and for several years had over 120 patients, most of whom were parish pauper cases. The 1850 plans show Number 8 as a fairly unpleasant set of bedroom cells. The magistrates state in 1837 that the place is suitable for 140 patients and a year later refer to the additional buildings appropriated to the pauper patients being constructed appropriately. They lamented that Charles was ill and no doctor was resident at the asylum. His son Austen was busy running his own asylum at Long Ashton and only visited when possible.

By 1842 when the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy visited, the Asylum routinely held 35 private patients and 100 or more paupers. Their report of 1844 blasted the place, declaring:

Kingsdown House, at Box, near Bath, was first visited in September, 1842. Amongst its great defects, is the want of airing-grounds. The space allowed for exercise, considering the number of Patients, is wholly insufficient. One of the wards, [almost certainly number 8] in which were fifty Female Paupers, had only a very small yard attached to it, and this, being on an abrupt descent and uneven throughout, was not only unfit for exercise, but was insufficient for half the number of Patients; and they were consequently congregated in a small room at one extremity of the yard. Every seat there was occupied, and the room itself being ill-ventilated, there existed an offensive odour that must have been detrimental to the bodily health of the Patients.

The airing courts for the Females is surrounded by very high walls, and is dull and cheerless, and the only yard for the Male Paupers is but little better.

They criticised the excessive use of restraint and the magistrates for not supervising the place better, and later stated that the place was illegal in not having a resident medical doctor (Charles lived at 24 The Circus, Bath).

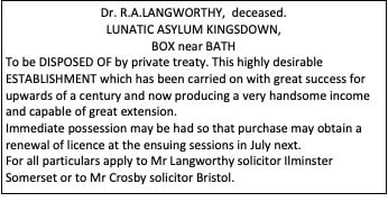

Charles Langworthy died in Bath in 1847 and left the freehold properties to Robert, who died on 23 May 1850 at Prospect House Box, recorded as: Death 23 May 1850: Robert Austin Langworthy, Physician. Of Serious Apoplexy, survived half a day.[8]

Charles died at a time when the Somerset County Lunatic Asylum was being built. His son Austen moved from Bristol to take over Kingsdown whilst still operating his own asylum at Long Ashton. He became mentally ill and was admitted himself to Fishponds Asylum. On his return he sold his Long Ashton Asylum business to a Bristol doctor (Dr Rogers) and effectively closed the pauper side of Kingsdown Asylum. The Somerset County Asylum opened in 1848 and took all the Somerset paupers, which was the main contract held at Kingsdown. Many private asylums closed over the 1850s as the new County Asylums removed

the pauper business; however, Kingsdown survived.

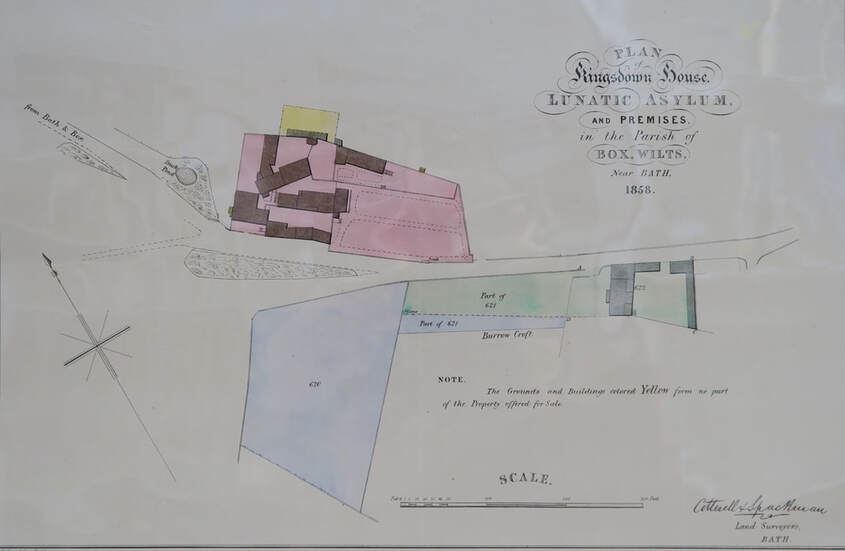

There is a vast plan in the Wiltshire Archive office of the asylum on a scale of ¼ inch to a foot. It is dated in the catalogue to 1850 but the sheets are not dated. It shows the asylum at probably its fullest extent and includes Prospect House as a ward. It is unclear how much this is a proposal or was already built but the main asylum site is shown as virtually identical to the buildings shown in the 1858 sale plan. The puzzle is why the plans would show a desire to enlarge the property by including Prospect House in 1850 when there were only 40 inpatients and no source of new pauper patients. The plans may in fact date from the 1840s or even possibly 1836.

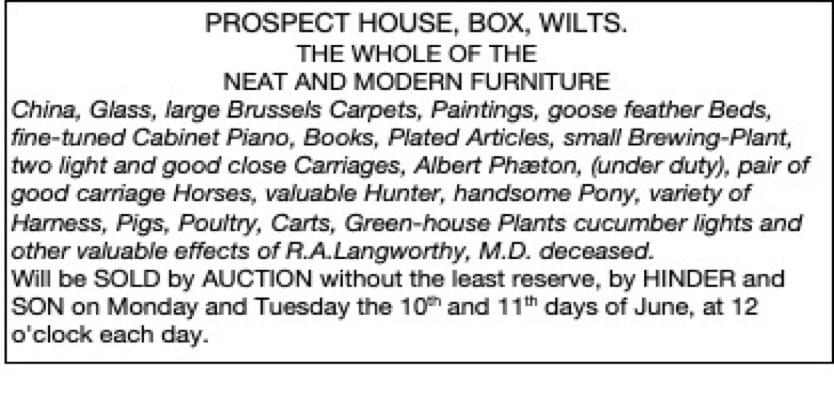

Both the Asylum and Austen’s possessions at Prospect House were put up for sale. It appears that Kingsdown House did not sell (the Lunacy Commissioner’s reports must have damned it for any buyer) and Austen’s widow Elizabeth then went into partnership with Dr John Nash.

Charles died at a time when the Somerset County Lunatic Asylum was being built. His son Austen moved from Bristol to take over Kingsdown whilst still operating his own asylum at Long Ashton. He became mentally ill and was admitted himself to Fishponds Asylum. On his return he sold his Long Ashton Asylum business to a Bristol doctor (Dr Rogers) and effectively closed the pauper side of Kingsdown Asylum. The Somerset County Asylum opened in 1848 and took all the Somerset paupers, which was the main contract held at Kingsdown. Many private asylums closed over the 1850s as the new County Asylums removed

the pauper business; however, Kingsdown survived.

There is a vast plan in the Wiltshire Archive office of the asylum on a scale of ¼ inch to a foot. It is dated in the catalogue to 1850 but the sheets are not dated. It shows the asylum at probably its fullest extent and includes Prospect House as a ward. It is unclear how much this is a proposal or was already built but the main asylum site is shown as virtually identical to the buildings shown in the 1858 sale plan. The puzzle is why the plans would show a desire to enlarge the property by including Prospect House in 1850 when there were only 40 inpatients and no source of new pauper patients. The plans may in fact date from the 1840s or even possibly 1836.

Both the Asylum and Austen’s possessions at Prospect House were put up for sale. It appears that Kingsdown House did not sell (the Lunacy Commissioner’s reports must have damned it for any buyer) and Austen’s widow Elizabeth then went into partnership with Dr John Nash.

Austen had gone bankrupt in 1834 and this later triggered a large series of court cases. In 1856 his creditors sued his estate for his outstanding debts and forced the sale of Kingsdown House in 1858. It was bought by the incumbent medical superintendent John Nash.

After the demise of the pauper business the Asylum shrank to having only 40 patients. The Commissioners kept asking that the pauper block be demolished as unfit for patients and this appears to have occurred between 1856 and 1860. The Asylum never expanded its numbers significantly again and the main role of the Nashes and later proprietors was to improve the quality of accommodation rather than to build large numbers of new bedrooms.

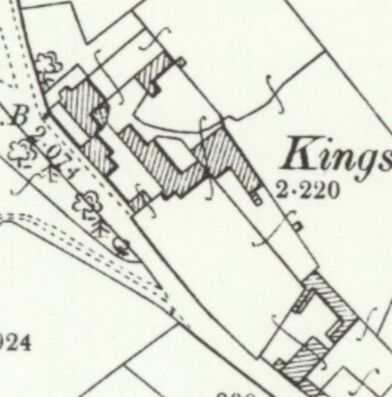

The Ordnance Survey map of 1882 (below left) shows the effect of these changes – building 8 is removed as is building 3, used for males in the 1850 plans. The building that currently exists over the road, running into the lower courtyard, had been built and probably had a bathroom and laundry on the ground floor. In 1867 the Commissioners noted the building of a new laundry and conversion of the old one [on the ground floor of number 6] to a sitting room and two bedrooms.

The Ordnance Survey map of 1882 (below left) shows the effect of these changes – building 8 is removed as is building 3, used for males in the 1850 plans. The building that currently exists over the road, running into the lower courtyard, had been built and probably had a bathroom and laundry on the ground floor. In 1867 the Commissioners noted the building of a new laundry and conversion of the old one [on the ground floor of number 6] to a sitting room and two bedrooms.

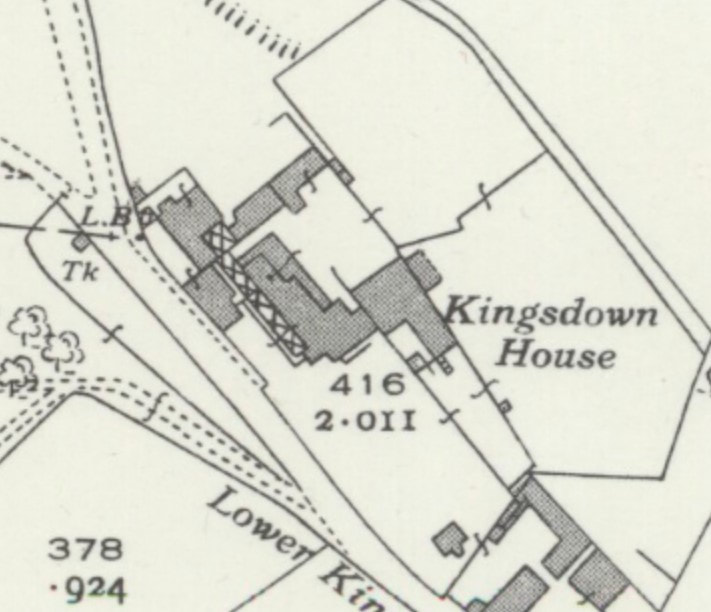

After the death of Joseph Nash, his widow Elizabeth Nash continued to operate the Asylum with a sequence of medical co-licensees. The commissioners talked of considerable alterations in 1890 but we do not have the plans for these. They appear to be the expansion of the male ward of number 11 and joining with the road archway as shown in the 1902 OS map (above right). In addition, extra land had been acquired below 11 as an extra airing court.

Henry Crawford MacBryan

Henry Crawford MacBryan become co-licensee in 1892 and Elizabeth Nash died a month later. He took over the Asylum. He was proprietor for almost 50 years and the commissioners’ talk of his early days were full of his improving the setup for 40 patients.

A garden wall was replaced by an iron fence to improve the view in 1897. A reliable water source was obtained and a mains gas supplied. Glass walkways were inserted and the old 1850s airing court wall removed in about 1903. This wall possibly had acquired the multiple graffiti that are still apparent where the stones were included in the roadside wall and in a shed at the end of the garden that is showing in a 1905 map.

Henry Crawford MacBryan become co-licensee in 1892 and Elizabeth Nash died a month later. He took over the Asylum. He was proprietor for almost 50 years and the commissioners’ talk of his early days were full of his improving the setup for 40 patients.

A garden wall was replaced by an iron fence to improve the view in 1897. A reliable water source was obtained and a mains gas supplied. Glass walkways were inserted and the old 1850s airing court wall removed in about 1903. This wall possibly had acquired the multiple graffiti that are still apparent where the stones were included in the roadside wall and in a shed at the end of the garden that is showing in a 1905 map.

The main change between the 1905 map and the 1939 OS map is the infill between building 9 and the main house. This was a music room built in 1905-06 but is now the garages. A walkway appears to have been inserted around the oldest buildings.

The sale in 1946 talked of a ballroom, but this may have been the music room. There was also mention of a kitchen garden and 21 acres of grounds, stables, cowhouse, and workshops.

Legend has it that the gates to the Asylum were sold when it closed and became the entrance to the Swindon Borough Council Crematorium.[9]

The sale in 1946 talked of a ballroom, but this may have been the music room. There was also mention of a kitchen garden and 21 acres of grounds, stables, cowhouse, and workshops.

Legend has it that the gates to the Asylum were sold when it closed and became the entrance to the Swindon Borough Council Crematorium.[9]

Buildings Summary

The building currently used as a garage is constructed in the roughest stone in the estate and could be the oldest (incidentally,

it appears to be the brewhouse in the 1850 plan). The imposing clock building (number 1 Kingsdown House) appears to date from between 1729 and 1754 (probably 1740s), built by James Jefferys, and either he or Zachariah built up patient numbers slightly later. The first expansion was probably in the buildings surrounding the upper courtyard. Charles Langworthy extended the number of buildings in the year 1836, when the asylum catered for more than an extra 100 pauper patients, holding eventually up to 140 patients.

After the pauper business collapsed the Asylum became an asylum for a smaller number of private patients, ranging from 20 to 45 depending on the energy of the proprietor. The newly-built building for pauper women was demolished in about 1857 and we then see minor alterations and improvements over the years.

It has been claimed that the wall graffiti around the walls of Kingsdown House - mainly in the garden walls and 1903 garden shed, might have come from Prospect House. This does not fit with its demolition in 1867 (and there is no evidence that patients ever stayed there other than the 1850 plan) and it is much more likely that the graffiti came from the old airing court walls that were demolished around 1900. These walls had provided entertainment for over 40 years to the bored inmates and as airing court walls, would have caused less concern with being graffitied than the inside of any building [a definite issue] or the outside of the main blocks. The shed some are in was built in about 1904. There are some in the building under the road archway. This is presumed to have been built in the 1890’s as clearly is the reuse of stone. This building probably required the removal of a courtyard wall, which may have been reused in the building.

The building currently used as a garage is constructed in the roughest stone in the estate and could be the oldest (incidentally,

it appears to be the brewhouse in the 1850 plan). The imposing clock building (number 1 Kingsdown House) appears to date from between 1729 and 1754 (probably 1740s), built by James Jefferys, and either he or Zachariah built up patient numbers slightly later. The first expansion was probably in the buildings surrounding the upper courtyard. Charles Langworthy extended the number of buildings in the year 1836, when the asylum catered for more than an extra 100 pauper patients, holding eventually up to 140 patients.

After the pauper business collapsed the Asylum became an asylum for a smaller number of private patients, ranging from 20 to 45 depending on the energy of the proprietor. The newly-built building for pauper women was demolished in about 1857 and we then see minor alterations and improvements over the years.

It has been claimed that the wall graffiti around the walls of Kingsdown House - mainly in the garden walls and 1903 garden shed, might have come from Prospect House. This does not fit with its demolition in 1867 (and there is no evidence that patients ever stayed there other than the 1850 plan) and it is much more likely that the graffiti came from the old airing court walls that were demolished around 1900. These walls had provided entertainment for over 40 years to the bored inmates and as airing court walls, would have caused less concern with being graffitied than the inside of any building [a definite issue] or the outside of the main blocks. The shed some are in was built in about 1904. There are some in the building under the road archway. This is presumed to have been built in the 1890’s as clearly is the reuse of stone. This building probably required the removal of a courtyard wall, which may have been reused in the building.

Conclusion

We are better able to date the origins of the Box madhouse from Peter Carpenter’s research. There is evidence that a madhouse was established in Box by 1697 when Samuel Young refuted an allegation that he was “Clapt up in the Madhouse at Box”. There are suggestions that Box was derived from or connected with an asylum in Batheaston documented in 1674.

The collection of buildings which together form Kingsdown House come from very different periods and dating them has helped to determine how the property altered to match societal changes over the centuries. We may find out more by dating the timbers in each area, but that is for another researcher.

We are better able to date the origins of the Box madhouse from Peter Carpenter’s research. There is evidence that a madhouse was established in Box by 1697 when Samuel Young refuted an allegation that he was “Clapt up in the Madhouse at Box”. There are suggestions that Box was derived from or connected with an asylum in Batheaston documented in 1674.

The collection of buildings which together form Kingsdown House come from very different periods and dating them has helped to determine how the property altered to match societal changes over the centuries. We may find out more by dating the timbers in each area, but that is for another researcher.

References

[1] Quoted by William Llewellyn Parry-Jones, The Trade in Lunacy, 1972, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.8. The long description by Edward Wakefield is in 1815 Report from the Committee on Madhouses in England, page 21

[2] Minute Book of the Men’s Meeting of the Society of Friends in Bristol 1667-1686, 26 April 1687

[3] Minute Book of the Men’s Meeting of the Society of Friends in Bristol 1667-1686. Bristol Record Society vol XXVI. Available online at https://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/bristolrecordsociety/publications/brs26.pdf, 15 February 1674

[4] Benjamin Coole, The Quakers cleared from being Apostates or the Hammerer defeated, & proved an Imposter, 1696, p.13

[5] Minute Book of the Men’s Meeting of the Society of Friends in Bristol 1667-1686. Bristol Record Society vol XXVI. Available online at https://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/bristolrecordsociety/publications/brs26.pdf, 19 July 1729

[6] A deed listed with no further detail other than it is a lease and release – a common means of transferring title - in the deeds of Kingsdown House listed in National Archives C15/286/F89

[7] MH51/735

[8] Bristol Times and Mirror, 8 June 1850, Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, 1 June 1850 and Devizes & Wiltshire Gazette, 6 June 1850

[9] Claimed without a reference, in P Dakin. ‘Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan aka Sir Roderick Glossop (PG Wodehouse’s ‘well known loony doctor’)’ J. Med. Biog. 2011 (19) 110

[1] Quoted by William Llewellyn Parry-Jones, The Trade in Lunacy, 1972, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.8. The long description by Edward Wakefield is in 1815 Report from the Committee on Madhouses in England, page 21

[2] Minute Book of the Men’s Meeting of the Society of Friends in Bristol 1667-1686, 26 April 1687

[3] Minute Book of the Men’s Meeting of the Society of Friends in Bristol 1667-1686. Bristol Record Society vol XXVI. Available online at https://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/bristolrecordsociety/publications/brs26.pdf, 15 February 1674

[4] Benjamin Coole, The Quakers cleared from being Apostates or the Hammerer defeated, & proved an Imposter, 1696, p.13

[5] Minute Book of the Men’s Meeting of the Society of Friends in Bristol 1667-1686. Bristol Record Society vol XXVI. Available online at https://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/bristolrecordsociety/publications/brs26.pdf, 19 July 1729

[6] A deed listed with no further detail other than it is a lease and release – a common means of transferring title - in the deeds of Kingsdown House listed in National Archives C15/286/F89

[7] MH51/735

[8] Bristol Times and Mirror, 8 June 1850, Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, 1 June 1850 and Devizes & Wiltshire Gazette, 6 June 1850

[9] Claimed without a reference, in P Dakin. ‘Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan aka Sir Roderick Glossop (PG Wodehouse’s ‘well known loony doctor’)’ J. Med. Biog. 2011 (19) 110