|

Sarah Olive Currant

Text and Photos John Currant with original extracts from Olive’s memoires July 2022 For a very long time there has been a great flow of people between Box and South Wales. Partly it was for work, when coal mining in Wales or stone quarrying in Box had economic downturns in the Victorian period. But this doesn’t give a full picture and many young people sought new opportunities in the different locations outside of these two industries. This was the story of Olive Currant who moved to Box in 1940 to further her nursing career and to aid in the war effort. My mother Sarah Olive Jones was born on 10 January 1920 and brought up as a Welsh-speaker in her parent’s home at the small village of Tumble, near Cross Hands in Carmarthenshire. She was a regular attender at St Non Chapel, five miles away, the most westerly non-Conformist church in Wales. This was a fiercely independent area famous for being part of the Rebecca Riots in the 1830s and 40s when farmers and agricultural workers dressed as women pulled down turnpike gates in protest against rises in taxes and tolls. Before each gate, the rioters enacted a small play justifying their need to pull down the gate so that the old Rebecca could pass by. It was once an area which mined anthracite, and a staunchly Rugby-supporting area, including the Welsh international Gareth Davies who was Olive's cousin. |

Olive’s Childhood Recalled

Olive recorded her early life for the grandchildren as an 85-year-old in 2006:

I was born in Aur-Awel, Cwm-Maur, Carmarthenshire, the fourth child of Elizabeth Mary and David John Jones. My father died in 1930 aged 36. He had tuberculosis and, after a few stays in the sanatorium, the doctors could do no more and so he died at home. My poor mother was left with six children, five still at school and my sister Margaret only two years old. Shortly after,

I contracted pleurisy which did not clear up so I was sent off to a sanatorium at the Adeline Patti Hospital, near Swansea, where

I stayed for about two years from the age of 10 until nearly 12. I missed the eleven plus whilst in hospital and left school at fourteen.

Olive recorded her early life for the grandchildren as an 85-year-old in 2006:

I was born in Aur-Awel, Cwm-Maur, Carmarthenshire, the fourth child of Elizabeth Mary and David John Jones. My father died in 1930 aged 36. He had tuberculosis and, after a few stays in the sanatorium, the doctors could do no more and so he died at home. My poor mother was left with six children, five still at school and my sister Margaret only two years old. Shortly after,

I contracted pleurisy which did not clear up so I was sent off to a sanatorium at the Adeline Patti Hospital, near Swansea, where

I stayed for about two years from the age of 10 until nearly 12. I missed the eleven plus whilst in hospital and left school at fourteen.

I used to visit my great grandmother, who had a smallholding in Tumble. She would urge us to drink the remains of the milk left over from the cheese whey. It was horrible. I couldn’t speak English until I went to school as we spoke only Welsh at home and

I was brought up as a non-conformist in the Congregational Church. Nonetheless, my first job was as a mother’s help to the vicar’s wife in the Parsonage, Court Henry, New Dryslwyn, earning 15 shillings a week, which I passed over in full to my mother.

I remember buying the vicar’s bicycle for 10 shillings and learned to ride aged 14, so that I could cycle home sometimes. I joined the church choir and was confirmed in the Anglican faith at Golden Grove Parish Church by the Bishop of St David’s, just a few miles away. When I left, I joined my sister and two step-sisters working at St Brides Hospital, Haverfordwest but left when my mother became ill and wanted me to look after her.

I was brought up as a non-conformist in the Congregational Church. Nonetheless, my first job was as a mother’s help to the vicar’s wife in the Parsonage, Court Henry, New Dryslwyn, earning 15 shillings a week, which I passed over in full to my mother.

I remember buying the vicar’s bicycle for 10 shillings and learned to ride aged 14, so that I could cycle home sometimes. I joined the church choir and was confirmed in the Anglican faith at Golden Grove Parish Church by the Bishop of St David’s, just a few miles away. When I left, I joined my sister and two step-sisters working at St Brides Hospital, Haverfordwest but left when my mother became ill and wanted me to look after her.

Olive Jones as a girl. Left: In her Confirmation clothes and Right: becoming an adult

In 1939, Kingsdown House was in great need of more staff and advertised for nurses in the Western Mail for: Wanted Immediately – An experienced nurse for Private Mental Home. Apply with particulars to Matron, Kingsdown House, Box.[1]

They also asked their own staff to recommend others. Olive later recalled:

My mother received a letter from the matron of Kingsdown House as I had been recommended by my friend Mona from Llanddarog, who was already there. My mother was now recovered and said that I could go in June 1940. I met my future husband Arthur Currant there on the first night. I thought he was a real gentleman and he carried my bags from the railway station. His friend Arthur Scobell (another railway man) was going out with Mona.

They also asked their own staff to recommend others. Olive later recalled:

My mother received a letter from the matron of Kingsdown House as I had been recommended by my friend Mona from Llanddarog, who was already there. My mother was now recovered and said that I could go in June 1940. I met my future husband Arthur Currant there on the first night. I thought he was a real gentleman and he carried my bags from the railway station. His friend Arthur Scobell (another railway man) was going out with Mona.

|

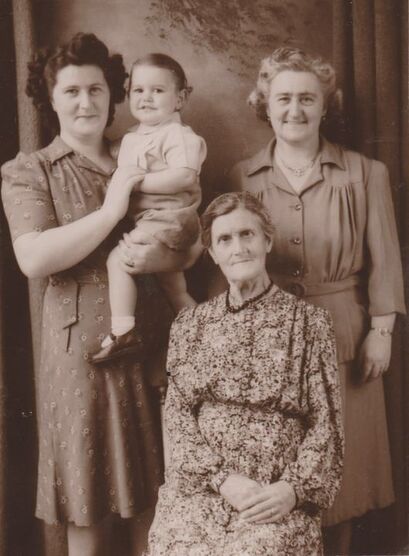

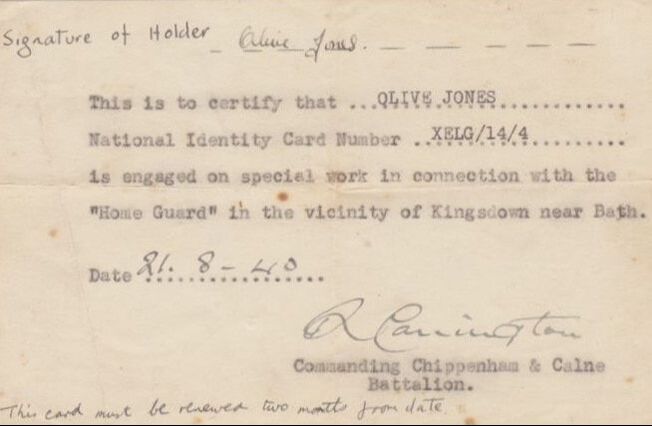

It must have been difficult for a young girl from a small, rural Welsh village to settle into a totally new area but Olive seems to have had no difficulty and clearly had talents recognised by her colleagues and employer. A year after her arrival, she was appointed to do special work in connection with the Home Guard in the vicinity of Kingsdown. Officially, women were not part of the country’s domestic front line because they were not allowed on combat duties. But some units did admit them, which obviously included Box in August 1940. In 1942 a Women’s Auxiliary Home Guard unit was allowed equipped with a bakelite brooch marked HG to identify members (not found in our family archives). She sometimes recalled that the nurses at Kingsdown were allowed pieces of a Spitfire fuselage as souvenirs when one crashed near the house. Left: Four generations of the Jones family L to R: Olive, John Currant (baby), great grandmother Morris (seated) and Elizabeth Mary Jones nee Richard (Olive’s mother) |

|

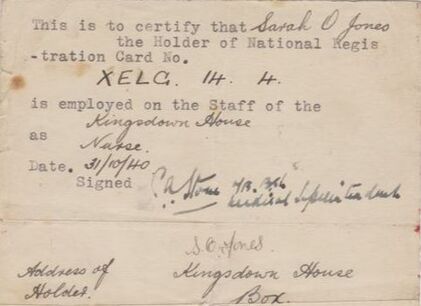

Olive’s Memories of Wartime Kingsdown In 1940-41 my friend Mona and I were seconded to the Home Guard. This meant that, coming off night duty, we were on guard duty at Kingsdown instead of going to bed. We were volunteered by the matron to do a few mornings each week. We would go to the pillbox by the Golf Clubhouse and used binoculars to look out for German parachutists who might be dropped to sabotage the railway and the power plants. We never did spy one – perhaps they were frightened of us two!! I spent some happy times in the war years, including dances at the old Bingham Hall with plenty of partners as there were hundreds of servicemen locally. Arthur had two left feet but he always met me at the end and walked me home safely. After two years, Mona and I moved to Bailbrook House, Batheaston. It was more money - £3 a month instead of £2 – but whilst I was there I witnessed the awful bombing of Bath. Right: Nursing staff at Kingsdown House in 1940 together with a patient in bed Below: Registration cards and Home Guard authentication |

Arthur and I became engaged and I started saving for our wedding. I went to work at Westinghouse, Chippenham, helping to make munitions. I lodged with the family of Ernest Hancock at 5 Mill Lane, Box and travelled on the train to Chippenham every day. It was the early train and there were dozens of Irishmen on board coming to work in the quarries.

Arthur and I were married on 16 January 1943 in my home church, Dewi Sant Church, Tumble (no bells allowed to be rung, as they were the warning sign of Nazi invasion). It had to be by special licence as I couldn’t get three weeks off for the banns and we weren’t supposed to have wedding cake with rationing but my mother’s cousin was a local baker and sorted something. I left Westinghouse when I became pregnant, the only reason we could leave. Because my mother was worried about me, I went to stay with them at the Cwm Mawr Club where my mother and stepfather were stewards.

Post-war Life in Box

Our first home was in Chippenham, not Box, at 12 Lowden. This meant that Arthur had to cycle back and forth every day, particularly as he had been promoted to be a railway ganger by then. He was on duty every day, even Sundays and Christmas Day, responsible for maintaining a section of the railway line and in charge of a group of engineers. In 1952 we were offered a council house in Box at 21 Brunel Way. It was a real treat as we had no bathroom and only an outside toilet in Chippenham.

We were there about eight years until we were offered the stewardship of the Comrades Legion Club. Arthur still continued on the railways during the daytime until he retired in 1971 and we moved to 7 Bargates. I had a part-time job at Ross Frozen Foods in The Ley as an invoice clerk until they made me redundant when they moved to Bristol. After Arthur’s death in February 1973,

I decided to pull my socks up and get a full-time job. I sat a Civil Service exam and started working for the Ministry of Defence (Navy) at Copenacre. My boss kept on at me to go for promotion and I became an Administrative Officer until I retired at the age of 65.

Our first home was in Chippenham, not Box, at 12 Lowden. This meant that Arthur had to cycle back and forth every day, particularly as he had been promoted to be a railway ganger by then. He was on duty every day, even Sundays and Christmas Day, responsible for maintaining a section of the railway line and in charge of a group of engineers. In 1952 we were offered a council house in Box at 21 Brunel Way. It was a real treat as we had no bathroom and only an outside toilet in Chippenham.

We were there about eight years until we were offered the stewardship of the Comrades Legion Club. Arthur still continued on the railways during the daytime until he retired in 1971 and we moved to 7 Bargates. I had a part-time job at Ross Frozen Foods in The Ley as an invoice clerk until they made me redundant when they moved to Bristol. After Arthur’s death in February 1973,

I decided to pull my socks up and get a full-time job. I sat a Civil Service exam and started working for the Ministry of Defence (Navy) at Copenacre. My boss kept on at me to go for promotion and I became an Administrative Officer until I retired at the age of 65.

Conclusion

Olive was a staunch supporter of numerous village societies. She said: Retirement in the village kept me busy as I was on several committees and a sidesman and reader in the church until old age and fibromyalgia slowed me up. She belonged to the WI, Luncheon Club, Box NATS, was chair of The Moonrakers and was always keen to learn more at the Workers’ Educational Association.[3]

Typical of her modesty and her commitment to her family, she left a bereavement note to her son John: John, do not grieve for me. I have had a good innings and am blessed with a wonderful son. I have just gone to join your father. For hymns I would like "Guide me, Oh Thou Great Jehovah" to the tune of Cwm Rhondda and "Jesu, lover of my soul". She was one of the best known, and well-liked residents in the village. What people remember about her, as Buffy Freeman said, is: her cheerfulness, her sense of humour and her Welsh accent.[4]

You can read more about Sarah Olive Jones and Arthur George Currant in a later article Life at Comrades Club

Olive was a staunch supporter of numerous village societies. She said: Retirement in the village kept me busy as I was on several committees and a sidesman and reader in the church until old age and fibromyalgia slowed me up. She belonged to the WI, Luncheon Club, Box NATS, was chair of The Moonrakers and was always keen to learn more at the Workers’ Educational Association.[3]

Typical of her modesty and her commitment to her family, she left a bereavement note to her son John: John, do not grieve for me. I have had a good innings and am blessed with a wonderful son. I have just gone to join your father. For hymns I would like "Guide me, Oh Thou Great Jehovah" to the tune of Cwm Rhondda and "Jesu, lover of my soul". She was one of the best known, and well-liked residents in the village. What people remember about her, as Buffy Freeman said, is: her cheerfulness, her sense of humour and her Welsh accent.[4]

You can read more about Sarah Olive Jones and Arthur George Currant in a later article Life at Comrades Club

References

[1] The Western Mail, 13, 14, 15 and 16 November 1939

[2] The Daily Herald, 17 March 1925

[3] Parish Magazine, December 2009

[4] Additional information Parish Magazine, July 1997

[1] The Western Mail, 13, 14, 15 and 16 November 1939

[2] The Daily Herald, 17 March 1925

[3] Parish Magazine, December 2009

[4] Additional information Parish Magazine, July 1997