|

Inside Box Mad House

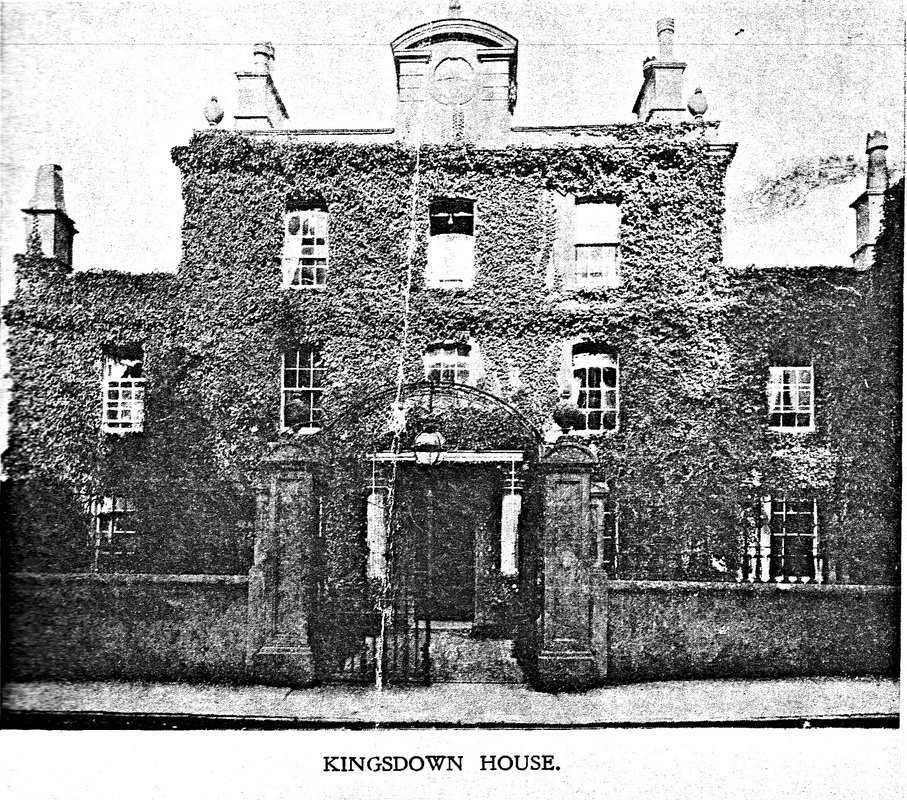

Jenny Hobbs, August 2015 Jenny Hobbs has lived in Kingsdown House for over forty years and assures us that there is certainly no existing aura of its sometimes sinister past. She and current residents kindly gave us unique access inside the property and grounds, to let us compare the building in 1903 with the modern property. The black and white illustrations are from Dr MacBryan's brochure recorded in The Hospital, 12 December 1903 (Courtesy Wiltshire History Centre and modern photos courtesy Carol Payne) |

History of Box Mad House

Kingsdown House, as it is now known, is a rambling building on the eastern hillside overlooking Box. Nowadays it is divided into seven separate houses, the largest being a pleasant Georgian fronted house surmounted by a clock tower. From the early 1900s until 1947 it was known as the Kingsdown Nursing Home. Prior to that it was known as the Box Mad House.

Kingsdown House, as it is now known, is a rambling building on the eastern hillside overlooking Box. Nowadays it is divided into seven separate houses, the largest being a pleasant Georgian fronted house surmounted by a clock tower. From the early 1900s until 1947 it was known as the Kingsdown Nursing Home. Prior to that it was known as the Box Mad House.

|

An early mention of the Mad House is in the Trowbridge Parish records of 1749. Mr James Jeffries was the owner and seems to have been a fairly enlightened proprietor of a lunatic asylum for those times. There exists a letter from him to the Trowbridge Parish Overseer showing concern over one of the patients, Mr John Porter, assuring them we will do our best for his recovery.

There are other letters from a patient, John Ruddle, a weaver by trade. He believed he was the King of Prussia and he wrote to his son addressing him as Prince Ferdinand, Prince of Brunswick. Jeffries also reported to the Parish Overseers, expressing regrets that he still persists in surprising odd whyms and fancies which undoubtedly might end in some bad consequences were he not under proper care. |

Incidentally, there is a story that the house was formerly Judge Jeffery’s hunting lodge and that a portrait of him hung in the hall until fairly recent times. However it seems more likely that history has become a little confused and that the portrait belonged to James Jeffries, the owner referred to above.

In 1814 the terms for men were 25s. per week but less for women who were not in such need of coercion ! The House also accommodated some parish paupers.

In 1815 a Parliamentary Select Committee was formed to investigate publicly- and privately-owned institutions for the insane.

The committee reported that an asylum had existed in Box for at least two hundred years.

In 1819 Edward Wakefield, a gentleman who combined his travels as a land agent with a philanthropic tour of inspection of madhouses wrote that at Langworthy’s House, Box (the proprietor, Charles Langworthy MD) there were forty patients and nine servants. He did not see the men because it was a day when they were not allowed up but he did see two women, nearly naked on straw in a cellar and four others completely naked on straw in a dark room. Wakefield commented in the course of my visiting these places I never recollect to have seen four living persons in such a wretched place.

Reports for 1837, 1841 and 1844 showed that approximately one hundred and forty patients were in residence.

In the mid-1800s there are also other reports from commissions in which Box Madhouse is castigated for its filthy conditions, overcrowding and its poor facilities for the pauper patients who were confined in outhouses. It was also censured for the excessive use of constraint at a time when physical constraint to prevent escape and harm to self and others was beginning to be frowned upon and more lenient treatment with vigilance and care by attendants was encouraged.

From the beginning of the 1900s the Mad House seems to have been run on more humanitarian lines under Dr MacBryan. It was advertised as a nursing home for ladies and gentlemen of the upper and middle classes, their personal servants and private carriages. Terms were from two to five guineas per week and about forty patients could be accommodated in comfortable and homelike surroundings where gas-lighting and hot water radiators had been installed. The forbidding stone walls around the grounds were pulled down and made into pretty gardens and lawns. These improvements were reputed to have cost £5,000. Restraint was never used and patients were encouraged to play golf and tennis, to go hunting and to visit Bath. A seaside residence was taken for the patients in summer.

The nursing home provided employment for the inhabitants of local cottages and those who remember or whose parents worked here seem to have happy memories.

In 1814 the terms for men were 25s. per week but less for women who were not in such need of coercion ! The House also accommodated some parish paupers.

In 1815 a Parliamentary Select Committee was formed to investigate publicly- and privately-owned institutions for the insane.

The committee reported that an asylum had existed in Box for at least two hundred years.

In 1819 Edward Wakefield, a gentleman who combined his travels as a land agent with a philanthropic tour of inspection of madhouses wrote that at Langworthy’s House, Box (the proprietor, Charles Langworthy MD) there were forty patients and nine servants. He did not see the men because it was a day when they were not allowed up but he did see two women, nearly naked on straw in a cellar and four others completely naked on straw in a dark room. Wakefield commented in the course of my visiting these places I never recollect to have seen four living persons in such a wretched place.

Reports for 1837, 1841 and 1844 showed that approximately one hundred and forty patients were in residence.

In the mid-1800s there are also other reports from commissions in which Box Madhouse is castigated for its filthy conditions, overcrowding and its poor facilities for the pauper patients who were confined in outhouses. It was also censured for the excessive use of constraint at a time when physical constraint to prevent escape and harm to self and others was beginning to be frowned upon and more lenient treatment with vigilance and care by attendants was encouraged.

From the beginning of the 1900s the Mad House seems to have been run on more humanitarian lines under Dr MacBryan. It was advertised as a nursing home for ladies and gentlemen of the upper and middle classes, their personal servants and private carriages. Terms were from two to five guineas per week and about forty patients could be accommodated in comfortable and homelike surroundings where gas-lighting and hot water radiators had been installed. The forbidding stone walls around the grounds were pulled down and made into pretty gardens and lawns. These improvements were reputed to have cost £5,000. Restraint was never used and patients were encouraged to play golf and tennis, to go hunting and to visit Bath. A seaside residence was taken for the patients in summer.

The nursing home provided employment for the inhabitants of local cottages and those who remember or whose parents worked here seem to have happy memories.

Kingsdown House

The current Kingsdown House was built in the early 1700s.[1] Between 1749 and 1763 the asylum was owned by James Jeffery but it is uncertain where he lived. By the 1820s the owner Dr Langworthy lived off the premises in a property called Prospect House.

The current Kingsdown House was built in the early 1700s.[1] Between 1749 and 1763 the asylum was owned by James Jeffery but it is uncertain where he lived. By the 1820s the owner Dr Langworthy lived off the premises in a property called Prospect House.

|

Original Building

The Asylum has historic origins in Box. In fact, an early map of the area refers to the road not as Doctors Hill but as Asylum Hill. The earliest part of the property is found at the back of the buildings. This was a small two-story cottage, an individual house rather than the present hamlet of buildings. It had a well in the back to service the domestic needs and this was an integral part of the development of the area. Left: This cottage at the rear of the complex was probably the original asylum. |

The Grounds

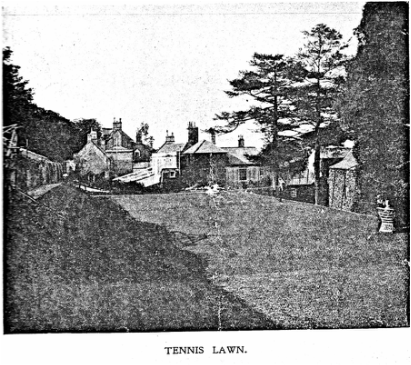

The most significant difference with the inside of the property is the amount of grounds that lie behind the austere entrance of Number 1. The grounds are impressive and appear to be separated for the use of different patients. The tennis lawn was clearly for the more active residents (and probably also the staff) and is still an impressive area, seen below looking towards Number 7.

The most significant difference with the inside of the property is the amount of grounds that lie behind the austere entrance of Number 1. The grounds are impressive and appear to be separated for the use of different patients. The tennis lawn was clearly for the more active residents (and probably also the staff) and is still an impressive area, seen below looking towards Number 7.

Acute Hospital Areas

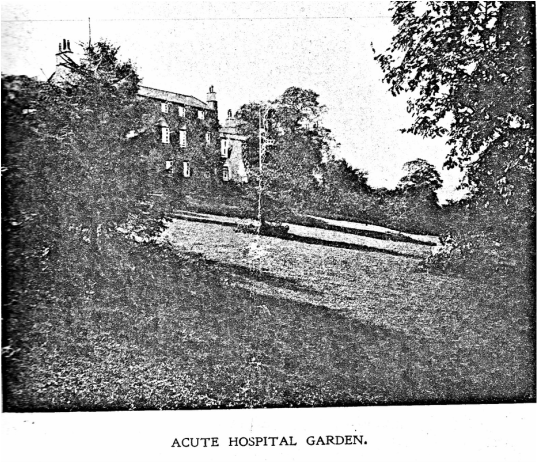

For the most-troubled patients there were gentle gardens where residents could perambulate at leisure when the weather permitted. The Acute Hospital ornamental garden was clearly well landscaped for the interest of long-term residents and the whole area intriguingly enclosed behind a folly wall with a decorated arch.

For the most-troubled patients there were gentle gardens where residents could perambulate at leisure when the weather permitted. The Acute Hospital ornamental garden was clearly well landscaped for the interest of long-term residents and the whole area intriguingly enclosed behind a folly wall with a decorated arch.

In the same way that the grounds were divided for different sorts of residents, so the buildings themselves had differing purposes from what we might now call a retirement home environment to that of a secure mental hospital. The most secure of these was the acute wing at Numbers 4 and 5.

|

Acute Asylum

At the rear of the properties were the Acute buildings for the needs of the most severely affected patients. Special arrangements (and more cost) was involved for residents that the 1903 brochure described as Homicidal, Suicidal and General Paralytic cases. Number 4 still had a padded room in the 1970s with a studded door and peep holes for the doctors to review disruptive patients without going inside the room. The peep hole is still in the door to the room, now filled in (see photo right). The rooms were small (now merged into one average size single room ) rather like secure cells. |

Acute Living Areas

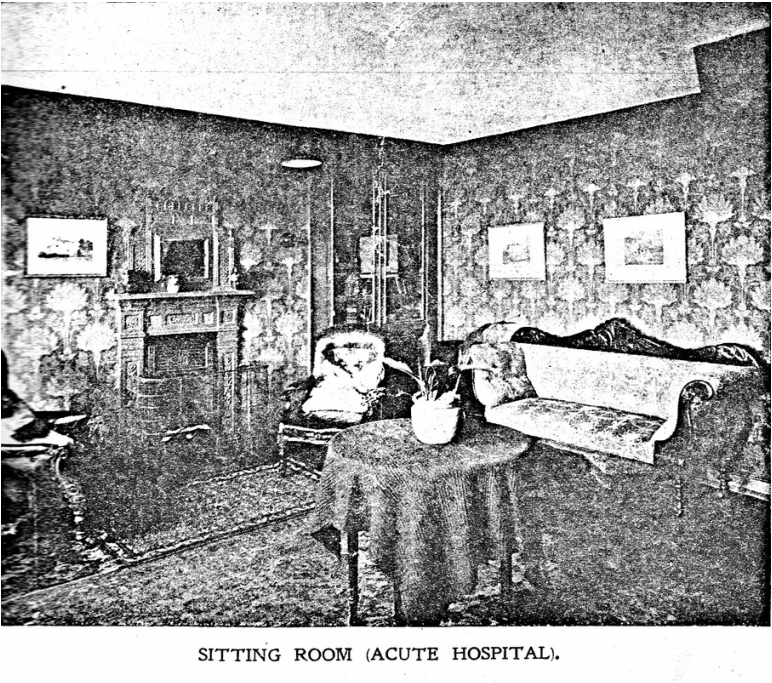

For some acutely-ill residents (perhaps including what we might call schizophrenia patients) there were residential areas for their use when life was more stable. These areas were mostly in the rear of the estate in wings now referred to as Numbers 5 and 6.

For some acutely-ill residents (perhaps including what we might call schizophrenia patients) there were residential areas for their use when life was more stable. These areas were mostly in the rear of the estate in wings now referred to as Numbers 5 and 6.

Sick Female Rooms

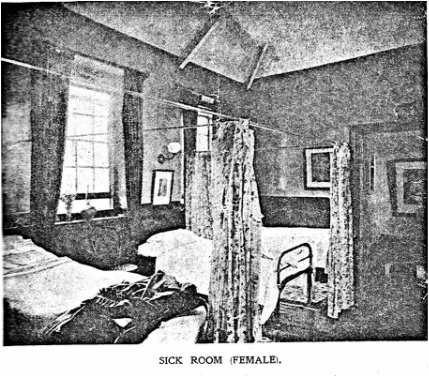

At the top of Number 4 was a room for female patients who required considerable bed care. Sometimes these might have been those suffering mental problems caused by old age or what we now call dementia.

At the top of Number 4 was a room for female patients who required considerable bed care. Sometimes these might have been those suffering mental problems caused by old age or what we now call dementia.

First Class Residents

For the First Class Residents (those patients who could afford two guineas up to five guineas a week) there was substantially better accommodation which could include personal servants and private carriages. These people were free to wander around the areas now called Number 3 and 7 and approved voluntary patients can be received into private parts of the house (the areas occupied by the resident doctors and senior staff).

First Class Ladies

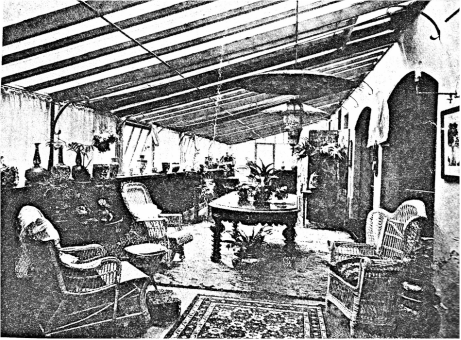

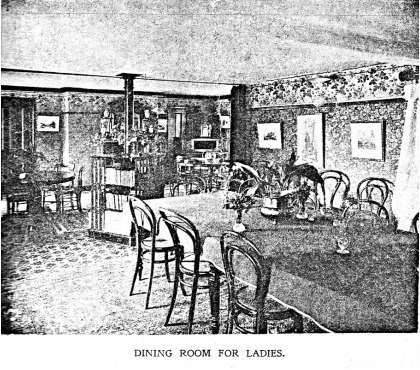

It was all rather genteel, as evidenced by the rooms for dining and relaxation. At the rear of Number 7 was a glass conservatory for use as the Ladies Lounge, seen below.

For the First Class Residents (those patients who could afford two guineas up to five guineas a week) there was substantially better accommodation which could include personal servants and private carriages. These people were free to wander around the areas now called Number 3 and 7 and approved voluntary patients can be received into private parts of the house (the areas occupied by the resident doctors and senior staff).

First Class Ladies

It was all rather genteel, as evidenced by the rooms for dining and relaxation. At the rear of Number 7 was a glass conservatory for use as the Ladies Lounge, seen below.

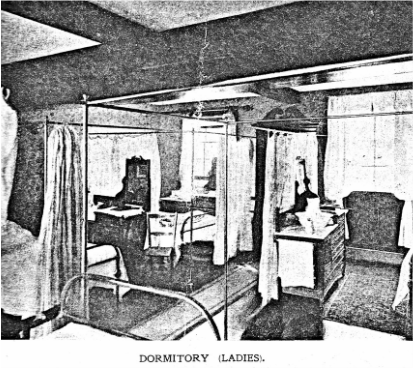

Assuring even greater care, male and female patients were largely kept in separate areas for dining and relaxation as well as the expected separation for sleeping arrangements.

For female patients there were plenty of books and 42 percent of the female patients were employed, although the nature of this was not specified.

First Class Gentlemen

Male residents had similar facilities to the women. Most of the male dining and sitting areas appear to be what is now called Number 3, although the room has been sub-divided now. There was a billiards room for recreation but it has not been possible to identify where this was.

Male residents had similar facilities to the women. Most of the male dining and sitting areas appear to be what is now called Number 3, although the room has been sub-divided now. There was a billiards room for recreation but it has not been possible to identify where this was.

The steeply sloped garden of Number 3 is not specifically marked as a gentleman's garden but it was probably more used by the men for reasons of convenience.

Staff Accommodation

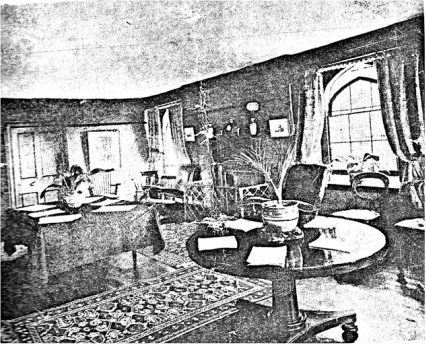

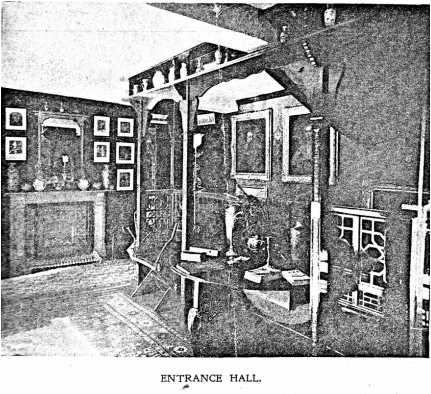

The main door and the entrance areas were for the use of the resident doctor and senior nursing staff. The 1903 brochure shows their living areas as rather grand, a retreat from the disadvantage of living in the establishment.

The main door and the entrance areas were for the use of the resident doctor and senior nursing staff. The 1903 brochure shows their living areas as rather grand, a retreat from the disadvantage of living in the establishment.

Unknown Mystery

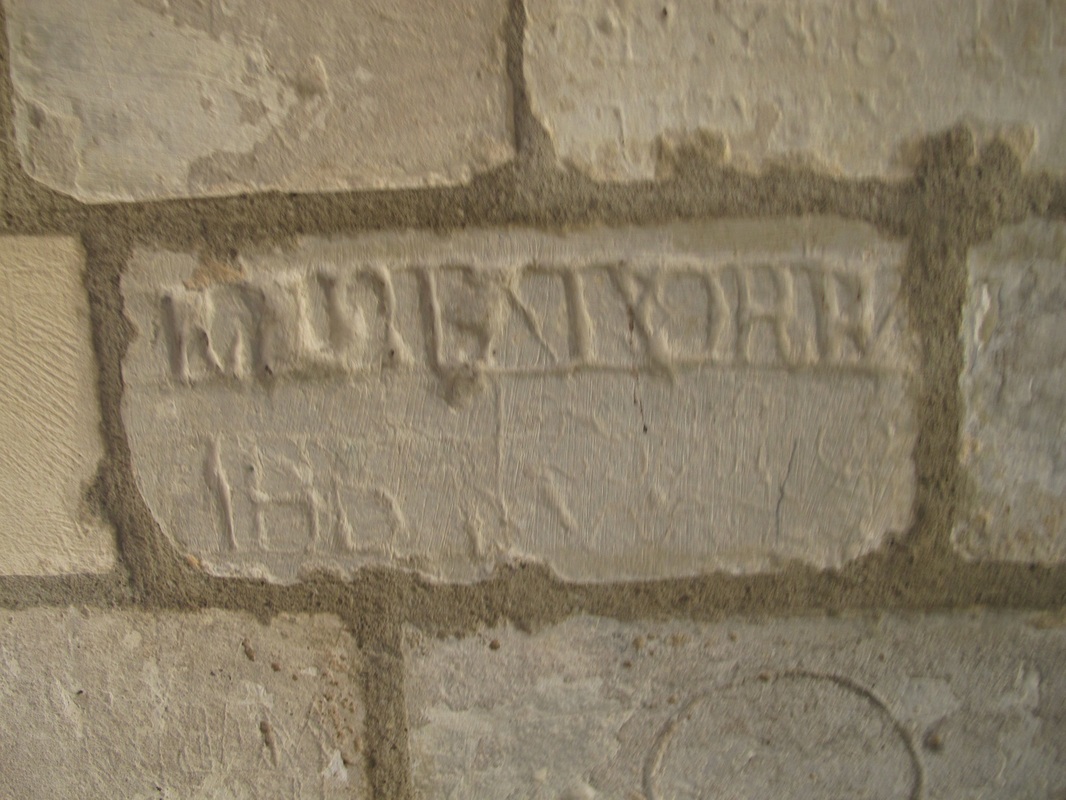

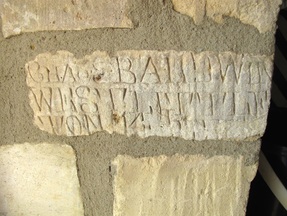

One of the most intriguing aspects of the house is the number of engravings on the stones of the houses and boundary walls. Was the graffiti carved by bored residents, perhaps an ex-quarryman? We don't know. The purpose and origin of these has been lost in time and any suggestions from readers would be welcomed. Here are some examples of the work.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the house is the number of engravings on the stones of the houses and boundary walls. Was the graffiti carved by bored residents, perhaps an ex-quarryman? We don't know. The purpose and origin of these has been lost in time and any suggestions from readers would be welcomed. Here are some examples of the work.