George Edward Northey, 1860 - 1932: Life at Cheney Court

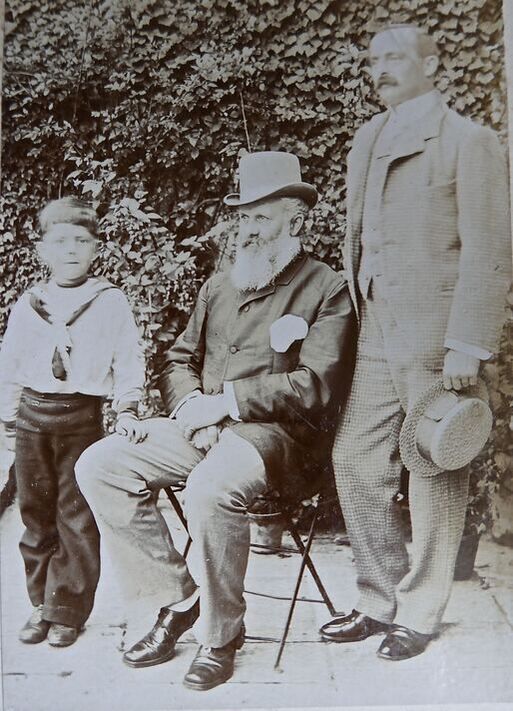

Alan Payne Family photos and research Diana Northey February 2020

Alan Payne Family photos and research Diana Northey February 2020

George Edward Northey inherited his part of the Wiltshire estate when he was 46 years old on his father's death in 1906. He was living at Manchester and working as the Prison Governor at Strangeways while supporting his wife and three children aged 19 to 9 years. He inherited his father's share in the estate and debts generated from the family's late Victorian lifestyle epitomised by a town house in Bath and a country estate in Box. George Edward was also required to support Ashley Manor and its occupants, including his dowager mother aged 68, two unmarried sisters, family friends and servants. It was a huge responsibility and probably not one that Edward relished.

In 1885 he had married Mabel Beatrice Helen Hunter (born in Boulogne, 1860), the daughter of Captain Hunter of Killylung, Dumfries, an Indian Army officer who had retired to Summerfield, Weston, Bath. Mabel knew the village well because her brother, Major Hunter, had lived at Ashley House, Box, for some time.[1] George Edward appears to have been content with his work and he continued as a prison governor until after the death of his mother (December 1907). He eventually resigned from his job in July 1908 and moved back to Box permanently.[2]

Northey Estate in 1908

George Edward was an outsider with little experience of running a country house and a landed estate. His acknowledgement speech at his first meeting of the Oddfellows in August 1909 tells of his difficulties: His family took the greatest interest in everything which went on in Box. They had been resident there now nearly a year and knew each other pretty well, and he hoped as years went on that good relations would continue to exist between them... (He) expressed his thanks for the kind references made to his family, and repeated that anything they could do to help them in Box they would always try to do, and he could assure them, although he realised it would be difficult to do so, he would try to follow in his father's footsteps.[3]

More significant than his personal circumstances were the economic circumstances in which the village found itself in the early 1900s. Repeated references to the stone trade in Box at this time refer to the decline of the quarry trade, reduction in Friendly Society membership in a large measure due to unemployment and the depression in trade locally.[4] The amalgamation of local firms into the Bath Stone Firms Ltd did not solve underlying problems, nor did the merger with the Portland stone business presaging the formation in 1911 of the Bath & Portland Stone Firms Ltd.

George Edward's Early Life

This is only half of the story, however, because, as a young man, George Edward had travelled to New Zealand to make his fortune and returned bankrupt and in disgrace. After school at Sherborne, eighteen-year-old Edward moved to Ashburton, Canterbury, New Zealand in 1878 and lived there for some years before going into business in a partnership with Charles Thornton Dudley in 1883 as farmers and graziers.[5] He ploughed £1,000 of his own money and borrowed £3,000 from his father to invest in the concern. After brief farming success, the partnership ventured into frozen meat exporting and lost a considerable amount of money because the refrigeration did not last for the whole journey. George Edward returned in 1885 and married Mabel Hunter from Bath on 10 June 1885. They set up life in England, living at The Bungalow, Ditteridge, which they built reminiscent of colonial houses in New Zealand.

However, he had neglected his financial affairs (or sought to avoid them) and in 1888 was sued for debts owed in New Zealand amounting to £11,705.19s.2d (equivalent in today's money to £1½million).[6] He had no books showing his transactions with his few separate creditors, who are principally tradesmen. It remains unclear if he was allowed to go bankrupt with assets of only £53.3s. or whether his father bailed him out in the end (probably the latter).

Seeking Employment

George Edward was obliged to take employment, hardly considered suitable for a gentleman. He appears to have flirted with the idea of military service and for six years was in the militia. He was appointed 2nd Lieutenant in the South Wales and Severn Division of the Royal Engineers Militia in 1890. He trained in submarine mining (control of mines at sea) at the School of Military Engineering but the army wasn't a career for him and he resigned in 1896.[7]

So he became a prison administrator in 1894, aged 34.[8] He worked as deputy governor at Walton Liverpool Prison and Wormwood Scrubs (1896) before taking charge of Kingston Prison Portsmouth (1898), Exeter Gaol (1901-04), Chelmsford (where he trained other officers), and Manchester Strangeways (1907-08).[9] He did well in the service, a man who Lord William Neville described as one: (He) had the highest respect for, not only personally, but also because of the manner in which he discharged his official duties, and treated the men generally ... I consider that any prison would be fortunate to have him as a Governor.[10]

We don't know what Mabel made of life in the prison service. In 1902 at Exeter Prison five inmates attempted an escape onto the roof of the prison hospital. She saw them and raised the alarm, whilst their son, Anson, climbed onto the roof of the Governor's house and directed the recapture. On another occasion, a notorious English burglar escaped when George and Mabel were absent on holiday by donning the Governor’s mackintosh and golf cap and calmly walked out of the gates.[11]

He had considerable administrative experience but this was a far cry from adequate training to run the Wiltshire estates, in which he had only a life tenant's interest through the trust established by his father in 1906 with trustees Herbert Hamilton Northey (his brother) and Sir Edward Northey of Epsom (his uncle).

George Edward was an outsider with little experience of running a country house and a landed estate. His acknowledgement speech at his first meeting of the Oddfellows in August 1909 tells of his difficulties: His family took the greatest interest in everything which went on in Box. They had been resident there now nearly a year and knew each other pretty well, and he hoped as years went on that good relations would continue to exist between them... (He) expressed his thanks for the kind references made to his family, and repeated that anything they could do to help them in Box they would always try to do, and he could assure them, although he realised it would be difficult to do so, he would try to follow in his father's footsteps.[3]

More significant than his personal circumstances were the economic circumstances in which the village found itself in the early 1900s. Repeated references to the stone trade in Box at this time refer to the decline of the quarry trade, reduction in Friendly Society membership in a large measure due to unemployment and the depression in trade locally.[4] The amalgamation of local firms into the Bath Stone Firms Ltd did not solve underlying problems, nor did the merger with the Portland stone business presaging the formation in 1911 of the Bath & Portland Stone Firms Ltd.

George Edward's Early Life

This is only half of the story, however, because, as a young man, George Edward had travelled to New Zealand to make his fortune and returned bankrupt and in disgrace. After school at Sherborne, eighteen-year-old Edward moved to Ashburton, Canterbury, New Zealand in 1878 and lived there for some years before going into business in a partnership with Charles Thornton Dudley in 1883 as farmers and graziers.[5] He ploughed £1,000 of his own money and borrowed £3,000 from his father to invest in the concern. After brief farming success, the partnership ventured into frozen meat exporting and lost a considerable amount of money because the refrigeration did not last for the whole journey. George Edward returned in 1885 and married Mabel Hunter from Bath on 10 June 1885. They set up life in England, living at The Bungalow, Ditteridge, which they built reminiscent of colonial houses in New Zealand.

However, he had neglected his financial affairs (or sought to avoid them) and in 1888 was sued for debts owed in New Zealand amounting to £11,705.19s.2d (equivalent in today's money to £1½million).[6] He had no books showing his transactions with his few separate creditors, who are principally tradesmen. It remains unclear if he was allowed to go bankrupt with assets of only £53.3s. or whether his father bailed him out in the end (probably the latter).

Seeking Employment

George Edward was obliged to take employment, hardly considered suitable for a gentleman. He appears to have flirted with the idea of military service and for six years was in the militia. He was appointed 2nd Lieutenant in the South Wales and Severn Division of the Royal Engineers Militia in 1890. He trained in submarine mining (control of mines at sea) at the School of Military Engineering but the army wasn't a career for him and he resigned in 1896.[7]

So he became a prison administrator in 1894, aged 34.[8] He worked as deputy governor at Walton Liverpool Prison and Wormwood Scrubs (1896) before taking charge of Kingston Prison Portsmouth (1898), Exeter Gaol (1901-04), Chelmsford (where he trained other officers), and Manchester Strangeways (1907-08).[9] He did well in the service, a man who Lord William Neville described as one: (He) had the highest respect for, not only personally, but also because of the manner in which he discharged his official duties, and treated the men generally ... I consider that any prison would be fortunate to have him as a Governor.[10]

We don't know what Mabel made of life in the prison service. In 1902 at Exeter Prison five inmates attempted an escape onto the roof of the prison hospital. She saw them and raised the alarm, whilst their son, Anson, climbed onto the roof of the Governor's house and directed the recapture. On another occasion, a notorious English burglar escaped when George and Mabel were absent on holiday by donning the Governor’s mackintosh and golf cap and calmly walked out of the gates.[11]

He had considerable administrative experience but this was a far cry from adequate training to run the Wiltshire estates, in which he had only a life tenant's interest through the trust established by his father in 1906 with trustees Herbert Hamilton Northey (his brother) and Sir Edward Northey of Epsom (his uncle).

Living at Cheney Court, Ditteridge

George Edward grew up in Ashley Manor as a child but left as soon as he was old enough. He never returned to the manor but set up an independent household at Cheney Court, Ditteridge. In 1910, Cheney Court was described as a delightful residence ... built in the Tudor style near the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth ... famed for its elaborate carved mantelpieces ... on the left (of the entrance hall) is a raised dais, which it is supposed was erected for Queen Henrietta Maria, the lower part of the hall being used by the Royal retinue.[12] Little wonder that George Edward and Mabel took up residence here after George Edward left his work in the Prison Service.

George Edward grew up in Ashley Manor as a child but left as soon as he was old enough. He never returned to the manor but set up an independent household at Cheney Court, Ditteridge. In 1910, Cheney Court was described as a delightful residence ... built in the Tudor style near the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth ... famed for its elaborate carved mantelpieces ... on the left (of the entrance hall) is a raised dais, which it is supposed was erected for Queen Henrietta Maria, the lower part of the hall being used by the Royal retinue.[12] Little wonder that George Edward and Mabel took up residence here after George Edward left his work in the Prison Service.

In 1910 George Edward and his wife Mabel celebrated their Silver Wedding Anniversary at Cheney Court.[13] They entertained the tenants of the estate, notables in the village, the cottage tenants and neighbours. Mabel commemorated the occasion by planting an oak tree outside The Bungalow on the path to Ditteridge Church. She graciously received presents of a pair of solid silver flower vases from the small holders and a pair of solid silver candelabra from the cottage tenants. In return the couple entertained about 250 people to tea until 6pm at which George Edward said, He had not had much opportunity of doing very much for them up to the present time, but if anything needed to be done ... he would be very pleased to do all that he possibly could.

At seven o'clock, sixteen tenant farmers arrived and were invited into the house to view the handsome silver strawberry dish with cream jug and sugar basin, gifts from the servants at Cheney Court. The tenant farmers presented the couple with a very handsome and massive solid silver rose bowl. Dinner was served in the garage, which had been converted into an almost ideal dining room. The word almost indicates it was not really satisfactory. In July that year George Edward and Mabel held a garden fete in the grounds of their house to raise funds for the Ditteridge Church organ restoration fund.[14] Stalls included pottery, fortune-telling, hoop-la, coconut shy, donkey rides and concerts on the croquet lawn and later dancing there.

Dispute with Box Parish Council

One of the recurring issues with George Edward's role as Lord of the Manor was his disagreement with the Box Parish Council, formed in 1893. These mostly concerned access to Kingsdown Common.[15] It started over the occupation of the Down by the Somerset Special Reserve in 1912 for a camp and constant firing from 6am including the use of machine guns. It also involved the occupation of the area by the Kingsdown Golf Club. The dispute really centred on George Edward's view of his manorial rights compared to the Council's role to protect commoners' rights of grazing and access. The Council objected to a letter written by Mr Northey to the newspaper as though the whole of Kingsdown belonged to him. The dispute was handled badly by both sides but shows George Edward’s views as an outsider into his perceived rights as Lord of the Manor.

At seven o'clock, sixteen tenant farmers arrived and were invited into the house to view the handsome silver strawberry dish with cream jug and sugar basin, gifts from the servants at Cheney Court. The tenant farmers presented the couple with a very handsome and massive solid silver rose bowl. Dinner was served in the garage, which had been converted into an almost ideal dining room. The word almost indicates it was not really satisfactory. In July that year George Edward and Mabel held a garden fete in the grounds of their house to raise funds for the Ditteridge Church organ restoration fund.[14] Stalls included pottery, fortune-telling, hoop-la, coconut shy, donkey rides and concerts on the croquet lawn and later dancing there.

Dispute with Box Parish Council

One of the recurring issues with George Edward's role as Lord of the Manor was his disagreement with the Box Parish Council, formed in 1893. These mostly concerned access to Kingsdown Common.[15] It started over the occupation of the Down by the Somerset Special Reserve in 1912 for a camp and constant firing from 6am including the use of machine guns. It also involved the occupation of the area by the Kingsdown Golf Club. The dispute really centred on George Edward's view of his manorial rights compared to the Council's role to protect commoners' rights of grazing and access. The Council objected to a letter written by Mr Northey to the newspaper as though the whole of Kingsdown belonged to him. The dispute was handled badly by both sides but shows George Edward’s views as an outsider into his perceived rights as Lord of the Manor.

|

Selling Up

In 1909 Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, introduced a tax on land values as a way of funding National Insurance measures. It has sometimes been seen as the measure which bankrupted the landed gentry but that wasn't the case in Box. George Wilbraham, Edward’s father, had already sold substantial parts of the estate to fund his lifestyle. Sales included the Bath Road (1880s), the Devizes Road (1890s), the High Street (1906). Other land had been given away, most notably to build the New Box Schools (1875). Between 1873 and 1894 it is estimated that the Northey estate reduced by half from its peak of 1,300 acres.[16] The sales were not the arbitrary whims of individuals but the agreed decision of the trustees of the estate. In 1912, the trustees agreed to put the whole of the Ashley estate up for sale. We might imagine that they had already made substantial efforts to sell the properties to a single buyer but there was no interest. By September 1912 the trustees were so desperate to sell that they put a brief advertisement in the Bath Chronicle, announcing the disposals to the world and the local public.[17] We don't know how all of this affected George Edward but it probably made him as an outsider even less connected to the history of the Northey family. Having sold whatever they could in 1912, the trustees held further auctions in 1919 and 1923, which we review in detail in a later article, Northey Sales. |

George Edward was somewhat ill-suited to running the estate and, by temperament, more of a Victorian than a modern leader of local society. But he was quite remarkable in his decision to sell and suffer the consequences of the reduction of status. The auctions would have been a terrible blow to the family's reputation and many local residents blamed George personally. In a later article we consider the long-term trends which caused the fall of the family long before George's time.

Wartime at Cheney Court

Various artefacts were shifted from Ashley Manor to Cheney Court in 1915. They had undertaken considerable improvements to the house and gardens, bowyers of climbing roses, a pergola of pears and the ground floor, once the chapel of the Court, but for centuries used as a lumber place, is now the dining room with the old oak showing in relief against solid bare freestone.[18] They found what they believed was a spy hole used by Queen Henrietta Maria.

George Edward and Mabel entertained about 30 convalescing soldiers from Corsham in the grounds in 1915.[19] The soldiers enjoyed tea and refreshments and George Edward made a most incongruous speech: How delighted (he and Mrs Northey) were to do anything for men in khaki... He was for six years in the Militia, so he might almost say he was an ex-officer himself ... If those present went out again into this strenuous war, he wished them good luck and good health. The guests were given a photo of the Court and cigarettes were freely available. We can understand a little why George Edward's speech was so inappropriate. For the boy who had been a failure in Australia, a disappointment to his military father and totally unused to speech-making, the disgrace had come home to roost with the sale of much of the Northey estate.

To make matters worse at this time, Anson Northey, George Edward's eldest son, was missing in action whilst serving with the Essex Regiment. He had been killed on 26 August 1914 in one of the first actions of the war and his body never recovered. It wasn't until 1916 that he was reported dead. George Edward never really recovered from so many losses in his life, particularly this personal one. George Edward performed various administration duties during the war: in 1914 chairman of the Box and Corsham Recruiting Committee, in 1915 Embarkation Officer at Southampton and in 1917 Railway Transport Officer at Victoria Station, London.[20]

Post-war Life

After the war George Edward assumed many roles of duty. He was a much-changed man, in 1920 adopting by deed poll the name Wilbraham, duplicating the custom of his father.[21] In 1908 he had been appointed a Justice of the Peace and in June 1921 he was appointed Deputy Lieutenant of Wiltshire.[22] For many years he served as a Justice of the Peace under the Lunacy Act administering the provisions of care at the Kingsdown Lunatic Asylum.[23]

He died aged 72 in 1932 and his funeral was at Ditteridge Church where the number attending was too large for the church and many listened from the churchyard. In contrast to his father’s funeral, George Edward’s flower-covered coffin was conveyed from Cheney Court through Ditteridge village to the church on a farm wagon by tenant and local farmer, Philip Goulstone. George Edward was buried near the west end of the Church. He left unsettled property (not in trust) of only £3,172.5s.7d and trust land of £18,000.[24] The trust land was held in the names of Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Hamilton Northey and Sir Edward Northey of Epsom, his younger brother and uncle.[25]

Mabel had spent much of her young life in France and Ditteridge was too rural for her background. She was a keen supporter of the RSPCA in Bath and moved to the city in 1933.[26] She died on 18 May 1941 at Park Street, Bath.

Various artefacts were shifted from Ashley Manor to Cheney Court in 1915. They had undertaken considerable improvements to the house and gardens, bowyers of climbing roses, a pergola of pears and the ground floor, once the chapel of the Court, but for centuries used as a lumber place, is now the dining room with the old oak showing in relief against solid bare freestone.[18] They found what they believed was a spy hole used by Queen Henrietta Maria.

George Edward and Mabel entertained about 30 convalescing soldiers from Corsham in the grounds in 1915.[19] The soldiers enjoyed tea and refreshments and George Edward made a most incongruous speech: How delighted (he and Mrs Northey) were to do anything for men in khaki... He was for six years in the Militia, so he might almost say he was an ex-officer himself ... If those present went out again into this strenuous war, he wished them good luck and good health. The guests were given a photo of the Court and cigarettes were freely available. We can understand a little why George Edward's speech was so inappropriate. For the boy who had been a failure in Australia, a disappointment to his military father and totally unused to speech-making, the disgrace had come home to roost with the sale of much of the Northey estate.

To make matters worse at this time, Anson Northey, George Edward's eldest son, was missing in action whilst serving with the Essex Regiment. He had been killed on 26 August 1914 in one of the first actions of the war and his body never recovered. It wasn't until 1916 that he was reported dead. George Edward never really recovered from so many losses in his life, particularly this personal one. George Edward performed various administration duties during the war: in 1914 chairman of the Box and Corsham Recruiting Committee, in 1915 Embarkation Officer at Southampton and in 1917 Railway Transport Officer at Victoria Station, London.[20]

Post-war Life

After the war George Edward assumed many roles of duty. He was a much-changed man, in 1920 adopting by deed poll the name Wilbraham, duplicating the custom of his father.[21] In 1908 he had been appointed a Justice of the Peace and in June 1921 he was appointed Deputy Lieutenant of Wiltshire.[22] For many years he served as a Justice of the Peace under the Lunacy Act administering the provisions of care at the Kingsdown Lunatic Asylum.[23]

He died aged 72 in 1932 and his funeral was at Ditteridge Church where the number attending was too large for the church and many listened from the churchyard. In contrast to his father’s funeral, George Edward’s flower-covered coffin was conveyed from Cheney Court through Ditteridge village to the church on a farm wagon by tenant and local farmer, Philip Goulstone. George Edward was buried near the west end of the Church. He left unsettled property (not in trust) of only £3,172.5s.7d and trust land of £18,000.[24] The trust land was held in the names of Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Hamilton Northey and Sir Edward Northey of Epsom, his younger brother and uncle.[25]

Mabel had spent much of her young life in France and Ditteridge was too rural for her background. She was a keen supporter of the RSPCA in Bath and moved to the city in 1933.[26] She died on 18 May 1941 at Park Street, Bath.

References

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 1 October 1932

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 25 July 1908

[3] The Wiltshire Times, 7 August 1909

[4] The Wiltshire Times, 7 August 1909

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 14 and 28 March 1889

[6] The Western Daily Press, 14 November 1888

[7] The Army and Navy Gazette, 4 October 1890, The Bath Chronicle, 12 June 1915 and The Wiltshire Times, 1 October 1932

[8] The Wiltshire Times, 1 October 1932 although Southend Standard and Essex Weekly Advertiser, 14 March 1907 puts the dates two years later.

[9] The Western Times, 3 February 1933 and Lloyds Weekly Newspaper, 15 November 1896

[10] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 26 January 1904

[11] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 1 October 1942

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 14 July 1910

[15] The Bath Chronicle, 31 August 1912

[16] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.106

[17] The Bath Chronicle, 21 September 1912

[18] The Bath Chronicle, 12 June 1915

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 12 June 1915

[20] The Wiltshire Times, 1 October 1932

[21] The Wiltshire Times, 22 May 1920

[22] Salisbury Times and South Wilts Gazette, 3 July 1908 and The Bath Chronicle, 11 June 1921

[23] For example, Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 13 October 1923

[24] The Bath Chronicle, 1 October 1932, Bath Chronicle and Herald, 24 December 1932 and The Evening News, 30 January 1933

[25] The Western Times, 3 February 1933

[26] The Wiltshire Times, 24 May 1941

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 1 October 1932

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 25 July 1908

[3] The Wiltshire Times, 7 August 1909

[4] The Wiltshire Times, 7 August 1909

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 14 and 28 March 1889

[6] The Western Daily Press, 14 November 1888

[7] The Army and Navy Gazette, 4 October 1890, The Bath Chronicle, 12 June 1915 and The Wiltshire Times, 1 October 1932

[8] The Wiltshire Times, 1 October 1932 although Southend Standard and Essex Weekly Advertiser, 14 March 1907 puts the dates two years later.

[9] The Western Times, 3 February 1933 and Lloyds Weekly Newspaper, 15 November 1896

[10] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 26 January 1904

[11] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 1 October 1942

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 14 July 1910

[15] The Bath Chronicle, 31 August 1912

[16] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.106

[17] The Bath Chronicle, 21 September 1912

[18] The Bath Chronicle, 12 June 1915

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 12 June 1915

[20] The Wiltshire Times, 1 October 1932

[21] The Wiltshire Times, 22 May 1920

[22] Salisbury Times and South Wilts Gazette, 3 July 1908 and The Bath Chronicle, 11 June 1921

[23] For example, Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 13 October 1923

[24] The Bath Chronicle, 1 October 1932, Bath Chronicle and Herald, 24 December 1932 and The Evening News, 30 January 1933

[25] The Western Times, 3 February 1933

[26] The Wiltshire Times, 24 May 1941