Earning Money Alan Payne December 2022

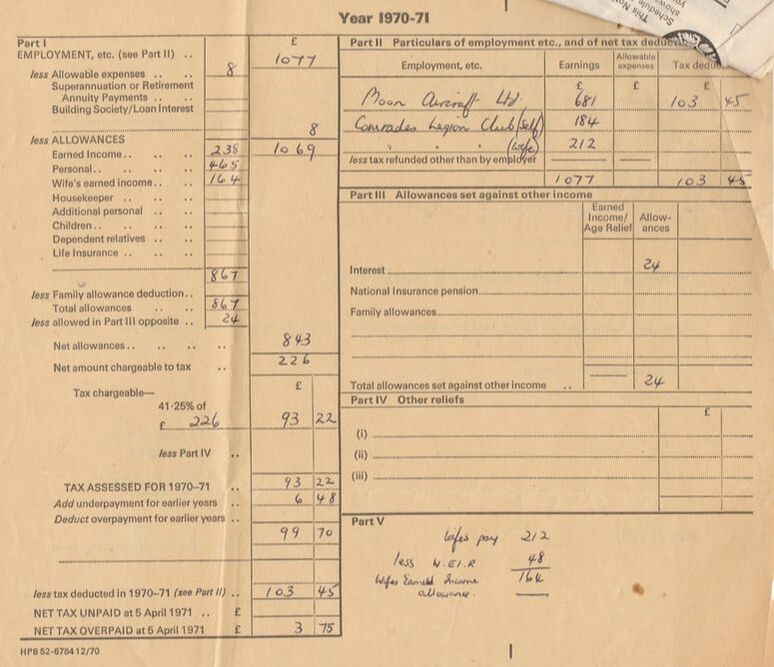

This wage slip shows income of £1,077 and tax of £99.70 for Arthur Currant in 1970-71. It isn’t for a month but for a whole year and the sources of income came from three different employments: Moon Aircraft Ltd, the Comrades Club for himself and the Comrades Club for his wife Olive. All of this was accepted as normal fifty years ago. This article seeks to explain what has changed since then and why.

Do you remember the days of naughtiness on television such as “The Likely Lads” and “The Liver Birds”? Or perhaps your heroes were in pop music including Mods and Rockers before the coming of Punk and New Wave? Do you remember half-a-crowns, threepenny bits or when a “bob” was worth something because a pint of beer cost 1 shilling and 10 pence, a gallon of petrol 4 shillings 8 pence and milk just 8 pence.[1] We can still enjoy music from these bands but it is money that seems so historic to us now. This article seeks to explain how money got to our present values.

Do you remember the days of naughtiness on television such as “The Likely Lads” and “The Liver Birds”? Or perhaps your heroes were in pop music including Mods and Rockers before the coming of Punk and New Wave? Do you remember half-a-crowns, threepenny bits or when a “bob” was worth something because a pint of beer cost 1 shilling and 10 pence, a gallon of petrol 4 shillings 8 pence and milk just 8 pence.[1] We can still enjoy music from these bands but it is money that seems so historic to us now. This article seeks to explain how money got to our present values.

Inflation and Employment

If you look at articles on the website for the Georgian and Victorian periods, you see references to interest rates of 4% per annum being the traditional, historic norm, plus or minus 1%. Stability was important because it meant that people could invest in government bonds or make bequests based on a regular, assured level of income. This rate of interest lasted from 1695 until the modern era when the rate was devastated and the value of the pound totally distorted. The erosion of capital meant that a sum of £100 in 1970 is equivalent in today’s purchasing power of over £1,600.[2]

Most of this change happened between 1971 and 1983 when interest rates soared to a high of 25% and Britain was called the sick man of Europe.[3] Inflation was just one of the problems for the Heath government of 1970-74 and for the Thatcher government of 1979 to 1990; they also had to deal with recession, high unemployment, and industrial disputes. British support for Israel in the Yom Kipper War led to an embargo of oil sales by Saudi Arabia and OPEC (the Organisation of Oil Producing Countries) reduced working hours in the UK to 3 days a week.

The relationship between the rate of employment and inflation is a complicated one. Some economists relate high unemployment with wages stagnation, the argument being that, with abundant labour, employers do not need to pay higher wages. At these times workers are doubly hit by lack of wages and rapidly rising prices.

Impact in Box

Changes in employment in Box in the 1970s were also dramatic and many traditional labourers found themselves out-of-work with little chance of re-training. In 1970 about half the population was employed in services (in Box meaning largely shops, hospitality and the Ministry of Defence), whilst the other half worked in manufacturing (in Box at Oscar Windebanks, Moon Aircraft or even Westinghouse, Chippenham). By 1990 only 1-in-5 people had production jobs. It was partly government initiative but also the inability of manufacturing to raise prices regularly.

The production of stone stopped during the Second World War in the Box and Corsham area with quarries held by the Ministry of Defence. The Central Armaments Depot was run down and closed in the mid-1960s and the aircraft factories and the workers’ hostels were closed and demolished.[4] Only Clift Quarry resuming quarrying operations after 1945 and that was commercially unviable hand-extraction.[5] The economics of installing expensive machinery were prohibitive in local quarries, which lacked electric cranes, conveyor systems, electric light and mechanised extraction equipment. Besides which, machinery was not really suitable to the extraction of stone blocks. It chewed up the stone too much and was affected by water in the workings. After a storm on Box Hill, it took up to 40 hours for the water to percolate through. So instead of blocks being quarried, crushed stone was extracted for concrete to satisfy building needs.

If you look at articles on the website for the Georgian and Victorian periods, you see references to interest rates of 4% per annum being the traditional, historic norm, plus or minus 1%. Stability was important because it meant that people could invest in government bonds or make bequests based on a regular, assured level of income. This rate of interest lasted from 1695 until the modern era when the rate was devastated and the value of the pound totally distorted. The erosion of capital meant that a sum of £100 in 1970 is equivalent in today’s purchasing power of over £1,600.[2]

Most of this change happened between 1971 and 1983 when interest rates soared to a high of 25% and Britain was called the sick man of Europe.[3] Inflation was just one of the problems for the Heath government of 1970-74 and for the Thatcher government of 1979 to 1990; they also had to deal with recession, high unemployment, and industrial disputes. British support for Israel in the Yom Kipper War led to an embargo of oil sales by Saudi Arabia and OPEC (the Organisation of Oil Producing Countries) reduced working hours in the UK to 3 days a week.

The relationship between the rate of employment and inflation is a complicated one. Some economists relate high unemployment with wages stagnation, the argument being that, with abundant labour, employers do not need to pay higher wages. At these times workers are doubly hit by lack of wages and rapidly rising prices.

Impact in Box

Changes in employment in Box in the 1970s were also dramatic and many traditional labourers found themselves out-of-work with little chance of re-training. In 1970 about half the population was employed in services (in Box meaning largely shops, hospitality and the Ministry of Defence), whilst the other half worked in manufacturing (in Box at Oscar Windebanks, Moon Aircraft or even Westinghouse, Chippenham). By 1990 only 1-in-5 people had production jobs. It was partly government initiative but also the inability of manufacturing to raise prices regularly.

The production of stone stopped during the Second World War in the Box and Corsham area with quarries held by the Ministry of Defence. The Central Armaments Depot was run down and closed in the mid-1960s and the aircraft factories and the workers’ hostels were closed and demolished.[4] Only Clift Quarry resuming quarrying operations after 1945 and that was commercially unviable hand-extraction.[5] The economics of installing expensive machinery were prohibitive in local quarries, which lacked electric cranes, conveyor systems, electric light and mechanised extraction equipment. Besides which, machinery was not really suitable to the extraction of stone blocks. It chewed up the stone too much and was affected by water in the workings. After a storm on Box Hill, it took up to 40 hours for the water to percolate through. So instead of blocks being quarried, crushed stone was extracted for concrete to satisfy building needs.

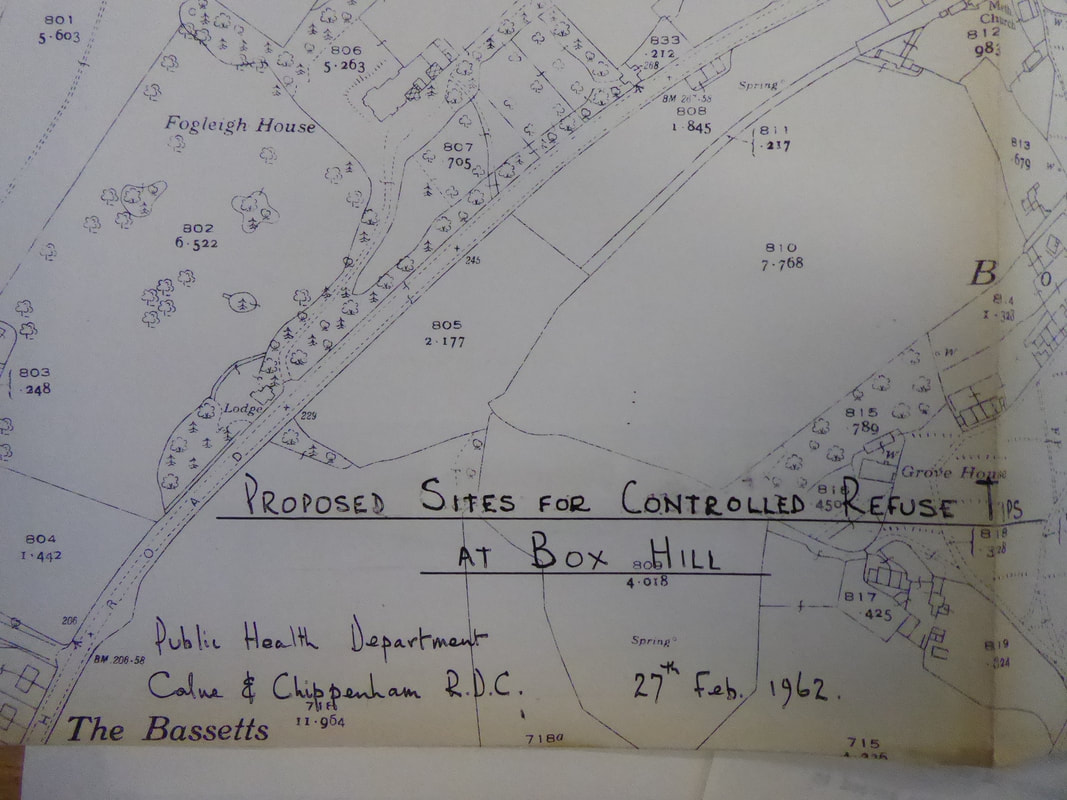

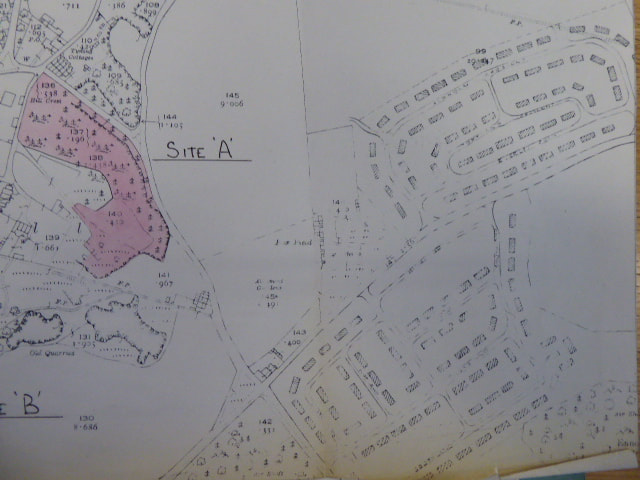

Planned tipping by the Rural District Council (courtesy Wiltshire History Centre via Varian Tye)

Meanwhile, the old quarries were simply used as dumping grounds. Richard Pinker recalled how one quarry was filled in with rubber tyres which were then set on fire in the early 1960s. Elm Park Quarry was used as an oil dump.[6] In 1969 a firm of contractors was authorised to recover scrap metal and to infill the entrances of many of the mineshafts with waste - a rather ignoble end to thousands of years of Box’s history, which effectively stopped any chance of revisiting some of the most famous natural historical museums in the story of quarrying.[7] Quarry spoil heaps were picked over for usable material and the rest dumped on Box Hill Common in the 1960s and 70s, until it was bulldozed flat. It was a tragic end to the stone industry which had been such a part of Box’s history.

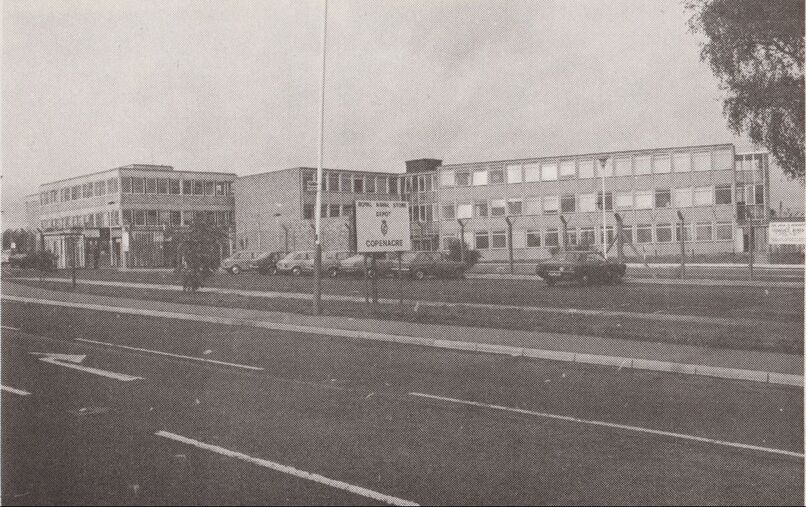

Copenacre

Some local underground quarries had been used for storage by the Royal Navy during the Second World War, including Copenacre Quarry, Spring Quarry and Sumsions. Based at Hartham, the Copenacre Royal Navy Storage Depot became a national storage site, often used for testing naval electronic equipment (particularly Asdic – now called Sonar - equipment).[8] Its importance continued after the war when the country’s defence relied increasingly on a nuclear submarine response during the Korean and Cold Wars. Copenacre extended in the years 1951-55, some buildings above ground and other subterranean areas for testing purposes.[9] Substantial parts of the Hartham surface buildings were constructed in 1957-59 when another navy depot at Risley, Lancashire, was closed and more staff came from London in 1966.[10] Early in 1968 staff from the Polaris American Weapons Group arrived. At its height in 1969, the Copenacre site employed 1,700 people, most of whom lived in Box and Corsham.[11] More staff resulted in increased Admiralty housing in the Leafy Lane area of Rudloe.

Some local underground quarries had been used for storage by the Royal Navy during the Second World War, including Copenacre Quarry, Spring Quarry and Sumsions. Based at Hartham, the Copenacre Royal Navy Storage Depot became a national storage site, often used for testing naval electronic equipment (particularly Asdic – now called Sonar - equipment).[8] Its importance continued after the war when the country’s defence relied increasingly on a nuclear submarine response during the Korean and Cold Wars. Copenacre extended in the years 1951-55, some buildings above ground and other subterranean areas for testing purposes.[9] Substantial parts of the Hartham surface buildings were constructed in 1957-59 when another navy depot at Risley, Lancashire, was closed and more staff came from London in 1966.[10] Early in 1968 staff from the Polaris American Weapons Group arrived. At its height in 1969, the Copenacre site employed 1,700 people, most of whom lived in Box and Corsham.[11] More staff resulted in increased Admiralty housing in the Leafy Lane area of Rudloe.

All this suddenly changed in 1972 when, reports of inadequate fire protection and to save money, the Admiralty proposed to move 900 jobs from Wiltshire to Hartlebury, Worcestershire. They were opposed by a coalition of the Transport and General Workers’ Union under Frank Cousins, local Members of Parliament led by Tony Benn and Daniel Awdry, the Bishop of Bristol and the Save Copenacre Committee of workers led by a group calling itself The Magnificent Seven. Local newspapers took up their cause and the Admiralty was forced to reverse its decision in October 1974.[12]

As the threat of war declined in the 1990s it was decided that the navy fleet would be cut and it was no longer viable to keep Copenacre. It closed with the loss of jobs in the period between September 1995 and March 1997.[13] The site was redeveloped in the spring of 2016 and considerable local employment opportunities were lost.[14]

Post-war Farming

Traditionally, it had been farming that dominated North Wiltshire employment but there have been enormous changes in local farming methods. The Second World War led to greater government scrutiny of farming under the control of the Ministry of Agriculture. There were regular inspections for levels of productivity, annual form-filling and numerous national reports. The Ministry brought positive benefits, however, including education, machinery pools, loans for buying tractors and guaranteed prices for certain produce.[15] The 1947 Agriculture Act introduced subsidies, encouraged high productivity, promoted scientific understanding and encouraged better management of farms. People believed that farmers had played their part in the war effort (unlike in World War I when they were seen as profiteers) and the countryside was promoted as an amenity offering fresh air and health. This concept was continued by the government with the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act.

There was much improvement to be done: in 1951 30% of dairy farms had no piped water and 50% no electric light.[16] Grants were made available towards capital projects under the Farm Improvement Scheme of 1957 which heralded a significant shift away from farmhouse cheese and butter making. Instead, farmers concentrated on milk production with cows in communal yards rather than stalls in cowhouses, mechanical milking, and milking parlours of various designs (herringbone, tandem and abreast).[17] Cleaner concrete walls and floors became general after 1950. All these changes contributed to the decrease in the number of people working on the land.

As the threat of war declined in the 1990s it was decided that the navy fleet would be cut and it was no longer viable to keep Copenacre. It closed with the loss of jobs in the period between September 1995 and March 1997.[13] The site was redeveloped in the spring of 2016 and considerable local employment opportunities were lost.[14]

Post-war Farming

Traditionally, it had been farming that dominated North Wiltshire employment but there have been enormous changes in local farming methods. The Second World War led to greater government scrutiny of farming under the control of the Ministry of Agriculture. There were regular inspections for levels of productivity, annual form-filling and numerous national reports. The Ministry brought positive benefits, however, including education, machinery pools, loans for buying tractors and guaranteed prices for certain produce.[15] The 1947 Agriculture Act introduced subsidies, encouraged high productivity, promoted scientific understanding and encouraged better management of farms. People believed that farmers had played their part in the war effort (unlike in World War I when they were seen as profiteers) and the countryside was promoted as an amenity offering fresh air and health. This concept was continued by the government with the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act.

There was much improvement to be done: in 1951 30% of dairy farms had no piped water and 50% no electric light.[16] Grants were made available towards capital projects under the Farm Improvement Scheme of 1957 which heralded a significant shift away from farmhouse cheese and butter making. Instead, farmers concentrated on milk production with cows in communal yards rather than stalls in cowhouses, mechanical milking, and milking parlours of various designs (herringbone, tandem and abreast).[17] Cleaner concrete walls and floors became general after 1950. All these changes contributed to the decrease in the number of people working on the land.

Conclusion

Inflation is one of the inequalities of modern life because some people have assets that increase whilst others find their experience is just rising cost. Arguably, leading the greatest inflationary boom has been our houses prices but these have caused a division between property-owners and property tenants. The solution remans to built more properties but that has been the case for many years. At the same time, local employment opportunities have declined.

Traditional manual labour in Box (stone mining, agriculture and servants etc) have declined and nowadays employment opportunities are more knowledge based. Other employment opportunities have come and gone, including shopping and local commerce. A new employment change may be around the corner with digital nomads working from home, which might have some benefits for Box.

The changes are enormous with comparatively little gained in return – except for one thing, the community-spirit that individual people have brought to the village. We need to ensure that friendliness continues as it is outsiders and young people who bring new ideas and enthusiasm to our society.

Inflation is one of the inequalities of modern life because some people have assets that increase whilst others find their experience is just rising cost. Arguably, leading the greatest inflationary boom has been our houses prices but these have caused a division between property-owners and property tenants. The solution remans to built more properties but that has been the case for many years. At the same time, local employment opportunities have declined.

Traditional manual labour in Box (stone mining, agriculture and servants etc) have declined and nowadays employment opportunities are more knowledge based. Other employment opportunities have come and gone, including shopping and local commerce. A new employment change may be around the corner with digital nomads working from home, which might have some benefits for Box.

The changes are enormous with comparatively little gained in return – except for one thing, the community-spirit that individual people have brought to the village. We need to ensure that friendliness continues as it is outsiders and young people who bring new ideas and enthusiasm to our society.

References

[1] Courtesy How much did things cost in 1960 - UK (retrowow.co.uk)

[2] Value of 1970 British pounds today | UK Inflation Calculator (in2013dollars.com)

[3] Originally used by Czar Nicholas I to describe the poor economic performance of Turkey under the control of the Ottoman Empire

[4] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.139-141

[5] R.J. Tucker, Box Freestone Mines, 1966, The Free Troglophile Association, p.8

[6] Wiltshire Life, February 2001

[7] Cotham Spelaeological Soc Memoirs Vol IV, 1968-9, p.4-5

[8] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.275 and Pat Whalley, Demise of the Copenacre site | Corsham Civic Society, 2016

[9] Patricia Whalley, History of Royal Naval Store Depot Copenacre, 1976, booklet, p.18-19

[10] Patricia Whalley, History of Royal Naval Store Depot Copenacre, 1976, p.23

[11] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.207

[12] Bath Evening Chronicle, October 1974

[13] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.212 and Pat Whalley, Demise of the Copenacre site | Corsham Civic Society

[14] rudloescene.co.uk - Copenacre

[15] History Extra Podcast, 18 October 2012

[16] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England & Wales, 1970, David & Charles¸ p.215

[17] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England & Wales, 1970, David & Charles¸ p.227-8

[1] Courtesy How much did things cost in 1960 - UK (retrowow.co.uk)

[2] Value of 1970 British pounds today | UK Inflation Calculator (in2013dollars.com)

[3] Originally used by Czar Nicholas I to describe the poor economic performance of Turkey under the control of the Ottoman Empire

[4] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.139-141

[5] R.J. Tucker, Box Freestone Mines, 1966, The Free Troglophile Association, p.8

[6] Wiltshire Life, February 2001

[7] Cotham Spelaeological Soc Memoirs Vol IV, 1968-9, p.4-5

[8] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.275 and Pat Whalley, Demise of the Copenacre site | Corsham Civic Society, 2016

[9] Patricia Whalley, History of Royal Naval Store Depot Copenacre, 1976, booklet, p.18-19

[10] Patricia Whalley, History of Royal Naval Store Depot Copenacre, 1976, p.23

[11] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.207

[12] Bath Evening Chronicle, October 1974

[13] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.212 and Pat Whalley, Demise of the Copenacre site | Corsham Civic Society

[14] rudloescene.co.uk - Copenacre

[15] History Extra Podcast, 18 October 2012

[16] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England & Wales, 1970, David & Charles¸ p.215

[17] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England & Wales, 1970, David & Charles¸ p.227-8