|

Early Northey Family of Box and Surrey

Alan Payne Family photos and research Diana Northey November 2019 In one respect the story of the Northey family is very complicated with two branches of the family, complex landholdings and two independent estates at Woodcote, Epsom, Surrey, and Box, Wiltshire. But we can see that the family members were comparatively straightforward - lawyers then military men, who invested their money into land to live off the rental income it generated. It wasn’t an uncommon background for upwardly mobile Georgian families, not sufficiently interested in buying aristocratic titles or power roles in politics. Much of the story of the Surrey branch has been recorded in detail but not so their life in Box.[1] The family weren't rural squires and references to hunting, shooting and fishing are rare in the records. Rather, they were local gentry, with town properties in Bath, with much of their lives spent in military roles and administration duties. Right: Sir Edward Northey (1652 - 1723) founder of the dynasty |

Early Northey Family

Sir Edward Northey (1652 - 1723) was a lawyer and politician who prosecuted and defended several high-profile cases, most notably serving as Attorney-General for William of Orange after he became the English king. It was a duty to which he was reappointed by Queen Anne and knighted in 1702. In 1686 he inherited a third share of the estate of Lady Philadelphia Wentworth, which amounted to £14,000 (somewhere around £3 million in today's money). She was the great great granddaughter of Mary Boleyn (sister of Anne Boleyn, Queen of England and wife of Henry VIII) and mother-in-law of the Duke of Monmouth who led the revolt against Charles II in 1685.

It was Sir Edward Northey who bought the first of the family’s property in Box as separate parcels of the old Speke estate in the early 1700s, when that family sold up after the death of George Petty Speke in 1719. We might imagine that the Box investment was a convenient country estate for over-wintering, close to the emerging Bath, where Beau Nash was prominent in developing the city after 1704.

He married Anne Jolliffe in 1687 and, on his death, he left a life interest to his wife who controlled it from 1723 until her death in 1743. Sir Edward specified that his second son Edward should inherit Woodcote at Epsom, since he had left most of his other property to the elder son, William senior (1689 – 1738), who had already spent a considerable amount of money on improving the family estate in Wiltshire. Sir Edward instituted a formal trust arrangement for the land after his wife’s life interest, which dominated family ownership in Box and Surrey throughout the Northey tenure, including a clause that only legitimate male heirs could inherit (a so-called tail male clause) which, as we shall see, caused additional complexity.

Like his father, William was a lawyer and held the role of Examiner in the court of Chancery from 1712-15, investigating cases about patent law and breeches of patents, for which his father paid the colossal sum of £6,000 (over a million pounds in today’s money). Such was the ability of Georgian office-holders to exploit public positions for their own financial advantage. William senior became Member of Parliament for Calne 1713-15 and later Wootton Bassett although it is unclear how much he attended Westminster. He probably never had the lordship of the Box trust lands which were controlled by his mother through her life interest in her husband’s trust in 1723. However, William did hold personal assets, such as Hazelbury Manor and Drewetts Mill which he bought on the death of Thomas Speke in 1726. His main estate was in Compton Bassett (acquired in 1715) and at Chippenham.

William senior outlived his father by 15 years but died in 1738, six years before his mother. We get some idea of her attitude to the Box estate in 1727 when, in connection with the Governors of Queen Anne’s Bounty lands of Box, she agreed to gift income for the benefit of the Rectory of Calstone, Wellington, the second church of Box’s vicar, Rev George Miller.[2] On his mother’s death, William Northey junior took over the Wiltshire estates.

William junior of Ivy House, 1722-70

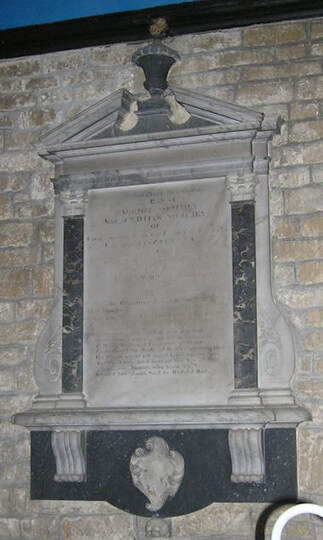

This William wasn’t based in Box, but lived at Compton Bassett and Ivy House, Chippenham, serving as Member of Parliament for both. William junior planted the grounds of Ivy House with specimens of North American trees and continued to live there until his death in 1770.[3] He didn’t ignore Box, however, and there is an epitaph to hima and his family in the vestry of Box Church:

Here lies the remains of William Northey Esq son of William Northey Esq of Compton Bassett, Wilts, by Abigail daughter to Sir Thomas Webster, Bart, of Battle Abbey, Sussex who departed this life December 24th 1770 in the 49th year of his age. He was a kind relation, a true friend, a warm patriot, and a most worthy man. He gained a compleat (sic) knowledge of the interests of Britain at Court independent in the Senate unbiased. This was true of his character to add more might appear ostentatious to say the least not doing justice to his memory. Also the remains of Lucy Northey his youngest daughter who died June 11th 1783 in the 15th year of her age. Reader:

Sir Edward Northey (1652 - 1723) was a lawyer and politician who prosecuted and defended several high-profile cases, most notably serving as Attorney-General for William of Orange after he became the English king. It was a duty to which he was reappointed by Queen Anne and knighted in 1702. In 1686 he inherited a third share of the estate of Lady Philadelphia Wentworth, which amounted to £14,000 (somewhere around £3 million in today's money). She was the great great granddaughter of Mary Boleyn (sister of Anne Boleyn, Queen of England and wife of Henry VIII) and mother-in-law of the Duke of Monmouth who led the revolt against Charles II in 1685.

It was Sir Edward Northey who bought the first of the family’s property in Box as separate parcels of the old Speke estate in the early 1700s, when that family sold up after the death of George Petty Speke in 1719. We might imagine that the Box investment was a convenient country estate for over-wintering, close to the emerging Bath, where Beau Nash was prominent in developing the city after 1704.

He married Anne Jolliffe in 1687 and, on his death, he left a life interest to his wife who controlled it from 1723 until her death in 1743. Sir Edward specified that his second son Edward should inherit Woodcote at Epsom, since he had left most of his other property to the elder son, William senior (1689 – 1738), who had already spent a considerable amount of money on improving the family estate in Wiltshire. Sir Edward instituted a formal trust arrangement for the land after his wife’s life interest, which dominated family ownership in Box and Surrey throughout the Northey tenure, including a clause that only legitimate male heirs could inherit (a so-called tail male clause) which, as we shall see, caused additional complexity.

Like his father, William was a lawyer and held the role of Examiner in the court of Chancery from 1712-15, investigating cases about patent law and breeches of patents, for which his father paid the colossal sum of £6,000 (over a million pounds in today’s money). Such was the ability of Georgian office-holders to exploit public positions for their own financial advantage. William senior became Member of Parliament for Calne 1713-15 and later Wootton Bassett although it is unclear how much he attended Westminster. He probably never had the lordship of the Box trust lands which were controlled by his mother through her life interest in her husband’s trust in 1723. However, William did hold personal assets, such as Hazelbury Manor and Drewetts Mill which he bought on the death of Thomas Speke in 1726. His main estate was in Compton Bassett (acquired in 1715) and at Chippenham.

William senior outlived his father by 15 years but died in 1738, six years before his mother. We get some idea of her attitude to the Box estate in 1727 when, in connection with the Governors of Queen Anne’s Bounty lands of Box, she agreed to gift income for the benefit of the Rectory of Calstone, Wellington, the second church of Box’s vicar, Rev George Miller.[2] On his mother’s death, William Northey junior took over the Wiltshire estates.

William junior of Ivy House, 1722-70

This William wasn’t based in Box, but lived at Compton Bassett and Ivy House, Chippenham, serving as Member of Parliament for both. William junior planted the grounds of Ivy House with specimens of North American trees and continued to live there until his death in 1770.[3] He didn’t ignore Box, however, and there is an epitaph to hima and his family in the vestry of Box Church:

Here lies the remains of William Northey Esq son of William Northey Esq of Compton Bassett, Wilts, by Abigail daughter to Sir Thomas Webster, Bart, of Battle Abbey, Sussex who departed this life December 24th 1770 in the 49th year of his age. He was a kind relation, a true friend, a warm patriot, and a most worthy man. He gained a compleat (sic) knowledge of the interests of Britain at Court independent in the Senate unbiased. This was true of his character to add more might appear ostentatious to say the least not doing justice to his memory. Also the remains of Lucy Northey his youngest daughter who died June 11th 1783 in the 15th year of her age. Reader:

|

In pity drop one kind or tender tear

For every virtue lies collected here Snatched off in all the bloom of pleasing youth A mind adorned with honor, goodness, truth To prove that souls angelic spurn this earth |

She raised our wonder then resigned her breath

To these so mourned in death so loved in life The afflicted parent and the widowed wife With tears inscribes this monumental stone That holds their ashes and expects her own. |

And added later, there is an additional epitaph which reads: Anne Northey wife of the above William Northey, Esq, who died December 30th 1822 aged 90 years.

|

His first wife Harriott also has an extensive family memorial in Box Church which reads:

Near this place lies interred the body of Harriott Northey wife of William Northey of Compton Bassett in the county of Wilts, Esq, daughter of Robert Vyner of Gantby in the county of Lincoln, Esq, who departed this life the 28th day of October 1750 aged 27. Also the remains of Anne Northey eldest daughter of the said William Northey Esq by Ann daughter of Edward Hopkins Esq of Coventry who died in August 1765 aged 12 years. If manners gentle, void of guile and strife Could health prolong and add to human life If manly sense and innocence of heart Could shield the stroke of death’s unerring dart Her friends would not regret life’s narrow span And she’d have liv’d beyond the age of man But gracious heaven who knew her virtues best Recalled her placid soul to blissful rest. Right: The Northey Memorial in Box Church kind permission of Phil Draper www.flickr.com/photos/churchcrawler/albums/72157623765890496 [4] |

Close by is another memorial to a daughter of William Northey of Ivy House:

In memory of Charlotte Northey daughter of the late William Northey Esq of Ivy House who after a painful and lingering illness which she bore with greatest patience and resignation died February 13th 1780 aged 28. There follows a poem:

In memory of Charlotte Northey daughter of the late William Northey Esq of Ivy House who after a painful and lingering illness which she bore with greatest patience and resignation died February 13th 1780 aged 28. There follows a poem:

|

It must be so! On terms so slight

Does Heaven its best good gifts bestow To point our fond affections right And wean us from a world below See all extinct the vital flame She lies consigned to sacred rest She who but now wher’ere she came Inspired with gladness every breast |

From this dark scene of human woes

Her spotless soul dismist away The full rewards of virtue knows And shines in God’s eternal day Celestial joys has she to share Whilst we our general loss deplore Since now of all that’s good and fair The brightest pattern is no more. |

We might imagine from these memorials that Box played an increasingly important part in the lives of the Northey family. Meanwhile, the other branch in Epsom fared less well and by 1808 there were no male heirs. So the Woodcote estate passed back to the successors of Williams senior and junior in the person of William of Hazelbury.

William of Hazelbury, 1752-1826

The eldest son of William junior has sometimes been called Wicked Billy a convenient way of separating him from the other family members called William. It is an unfortunate name, apparently given by his clerical nephew and one which stops us getting a full picture of the man. Born at Compton Bassett, Billy inherited his trust interest in the Box estate from his father in 1770 and established his home at Hazelbury Manor. The Wiltshire estate that Billy inherited was smaller than in his father’s time because the Calne property was sold by William junior to Lord Shelburne. It is uncertain but William of Hazelbury may have married Mary Huntington of Bedford Square, Bloomsbury, London in July 1795. If so, they had no children.

Billy had a 30-year parliamentary career and mostly voted to support his sponsor, the Duke of Northumberland, and the Whig opposition. Apparently, he never uttered in debate but was a largely loyal supporter of his patron and the Whigs cause led by Charles James Fox.[5] We might describe such a person as shy, unambitious and loyal but not wicked. His reputation seems to come from local anecdotes about wild parties with the Prince of Wales at Hazelbury but there is no real evidence to confirm this.

Quite the opposite, local newspaper references are purely factual. In 1780 offering a reward of 1 guinea for information about the theft of fruit and garden stuff from Ashley House (presumed to mean Ashley Manor), near Box.[6] Ashley Manor may have been a property for William’s siblings because in 1790 the youngest daughter of Captain Northey of 32nd Regiment (William junior), Miss Charlotte Northey, died at Ashley.[7] Her will dated 3 March 1789 calls her Charlotte Northey, Spinster of Box.[8] In 1789 Billy presented Henry Hawes to the rectory of Ditteridge.[9]

Billy’s will is largely unremarkable, although it makes clear that he identified himself as of the parish of Box. It expressed his wish to be buried in Box Church in that same manner as my late father was there buried and at a greater expense than was laid out in his funeral. But when it came to his burial, the memorial to Billy in the vestry was rather brief: In memory of William Northey Esq eldest son of William Northey Esq of Ivy House who died January 21st 1826 aged 73.

The will lists in detail the succession of Billy’s personal estate, depending on survived: first, his brother Edward, then to Edward’s sons, then Richard Northey Hopkins (his brother who changed his surname when he inherited through his wife’s family), then the daughters of Edward, and lastly to James Murray Northey (relationship uncertain). More unusually he left £100 to be shared out amongst his servants to provide one year’s wages in addition to what was due to them.

The eldest son of William junior has sometimes been called Wicked Billy a convenient way of separating him from the other family members called William. It is an unfortunate name, apparently given by his clerical nephew and one which stops us getting a full picture of the man. Born at Compton Bassett, Billy inherited his trust interest in the Box estate from his father in 1770 and established his home at Hazelbury Manor. The Wiltshire estate that Billy inherited was smaller than in his father’s time because the Calne property was sold by William junior to Lord Shelburne. It is uncertain but William of Hazelbury may have married Mary Huntington of Bedford Square, Bloomsbury, London in July 1795. If so, they had no children.

Billy had a 30-year parliamentary career and mostly voted to support his sponsor, the Duke of Northumberland, and the Whig opposition. Apparently, he never uttered in debate but was a largely loyal supporter of his patron and the Whigs cause led by Charles James Fox.[5] We might describe such a person as shy, unambitious and loyal but not wicked. His reputation seems to come from local anecdotes about wild parties with the Prince of Wales at Hazelbury but there is no real evidence to confirm this.

Quite the opposite, local newspaper references are purely factual. In 1780 offering a reward of 1 guinea for information about the theft of fruit and garden stuff from Ashley House (presumed to mean Ashley Manor), near Box.[6] Ashley Manor may have been a property for William’s siblings because in 1790 the youngest daughter of Captain Northey of 32nd Regiment (William junior), Miss Charlotte Northey, died at Ashley.[7] Her will dated 3 March 1789 calls her Charlotte Northey, Spinster of Box.[8] In 1789 Billy presented Henry Hawes to the rectory of Ditteridge.[9]

Billy’s will is largely unremarkable, although it makes clear that he identified himself as of the parish of Box. It expressed his wish to be buried in Box Church in that same manner as my late father was there buried and at a greater expense than was laid out in his funeral. But when it came to his burial, the memorial to Billy in the vestry was rather brief: In memory of William Northey Esq eldest son of William Northey Esq of Ivy House who died January 21st 1826 aged 73.

The will lists in detail the succession of Billy’s personal estate, depending on survived: first, his brother Edward, then to Edward’s sons, then Richard Northey Hopkins (his brother who changed his surname when he inherited through his wife’s family), then the daughters of Edward, and lastly to James Murray Northey (relationship uncertain). More unusually he left £100 to be shared out amongst his servants to provide one year’s wages in addition to what was due to them.

| william_of_hazelbury_will.docx | |

| File Size: | 14 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

The succession of the Northey property was plunged into disarray when William died without a legitimate heir. Having had a similar problem with the Epsom estate two decades earlier, the line could have disintegrated into a mass of legal wrangles between the family had it not been for the trust which defined how the succession would work in these circumstances. The properties in Wiltshire and Surrey should have gone to William’s younger brother, the Rev Edward Northey but he relinquished the inheritance and it passed to his two children, Colonel Edward Richard Northey and William Brook Northey.

Rev Edward appears to have been something of an outsider. He was a working clergyman who married the daughter of a clergyman from Kent. As adults they never occupied the family homes at Epsom or Box and Rev Edward was buried in St George’s chapel, Windsor, where he served as treasurer to the body of canons. He allegedly disapproved of the lifestyle of William of Hazelbury, calling him Wicked Billy and having nothing to do with him. In passing, it is worth noticing that Charlotte Taylor, the wife of Rev Edward, had the family surname Brook, that was used as a Christian name for one son.

Rev Edward appears to have been something of an outsider. He was a working clergyman who married the daughter of a clergyman from Kent. As adults they never occupied the family homes at Epsom or Box and Rev Edward was buried in St George’s chapel, Windsor, where he served as treasurer to the body of canons. He allegedly disapproved of the lifestyle of William of Hazelbury, calling him Wicked Billy and having nothing to do with him. In passing, it is worth noticing that Charlotte Taylor, the wife of Rev Edward, had the family surname Brook, that was used as a Christian name for one son.

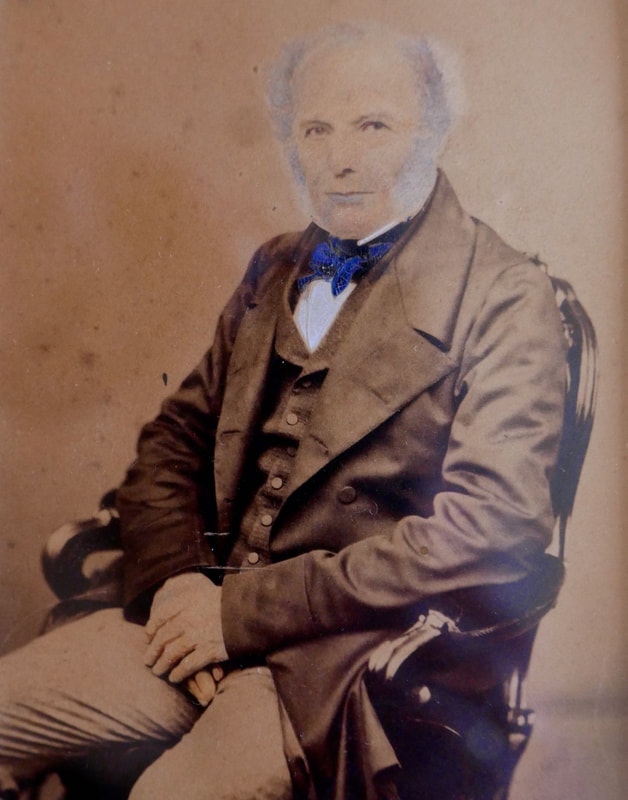

Above Left: Charlotte, daughter of Sir George Anson who married Rev Edward Richard Northey (above right).

Colonel Edward Richard Northey and William Brook Northey

These men held the lordship of Box jointly. They were both military men, serving abroad for considerable periods but they were very different in personality. Colonel Edward Richard (1795 - 1878) served with 52nd Light Infantry in Napoleonic Wars ending at the Battle of Waterloo. He was present throughout the Peninsula War including the 1812 Battle of Vitoria, Spain, when Wellington's troops defeated Joseph Bonaparte. It was a decisive moment in the Peninsula War and was recalled in the book Sharpe's Honour. At the battle, Sir Harry Smith told the story of how Edward Richard was knocked down by the wind of his shot and his face as black as if he had been two hours in a pugilistic ring.[10] On his return to England Edward Richard married Charlotte Anson in 1828. More family Christian names derive from this generation, including Anson and Charlotte's brother-in-law was Edward Bootle-Wilbraham (later Baron Skelmersdale). Col Edward Richard used Woodcote, Surrey, as his main home in the UK, which he inherited personally on the death of his father in 1828 but it was his second son who eventually made Box his home.

William Brook Northey, brother of Col Edward Richard, was also a military man (the Coldstream Guards) but, in contrast, was more involved in the village, often in the minutiae of arrangements. On 21 October 1842 at the Chequers Pub, William Brook was instrumental in forming a new Oddfellows Lodge in Box, called after him as the Loyal Northey Lodge. About 40 gentlemen sat down to entertainment, food and wine which reflected the highest credit on the taste and liberality of the host, Mr Vezey.[11] It was a significant development whose purpose was to support members with provision against sickness, death and usual misfortune. The lodge was actively involved in village life, for many decades running an annual fete at Fete Field (now Bargates) along with the Foresters and the Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes. The fete only ceased totally after the Second World War.

There were a number of significant gifts of land to the village during the trustees’ joint tenure of the estates. After the tragic death of the vicar’s wife Elizabeth Horlock and sister-in-law Alice Suddell in 1858, they gifted land for the building of Box Cemetery at the instigation of the estate solicitor Mr Mant.[12] It was a significant act of generosity, in some ways the epitaph of Mr Mant, the long-serving legal agent of the family in Box who died later that year and was succeeded by William Adair Bruce.[13] The same generosity was evident in the 1870s when the trustees gave land for the building of the Box Schools in 1875 and installed a water supply to the east of the village which flowed into the Poynder Fountain as well as the properties which developed on this side of Box.

We get some idea of the difficulty in funding the estate from contemporary snippets of information. With farming under increasing financial pressure in 1843, ten percent of the half-year’s rent was returned to tenants by ER and WB Northey.[14] Around this time the trustees sought alternative fundraising methods with the Kingsdown Fair, said to be not a fair in the legal sense of the word or in any way an incorporeal hereditament but simply the occupation of Kingsdown for several consecutive days for a horse, sheep and other cattle fair, the animals being placed in pens on the down and payments being thereupon made for pens etc.[15]

In 1840 they changed the date of Kingsdown Fair from Michaelmas (29 September) to roughly a fortnight earlier, to be held 16 September in 1840 and thereafter the first Wednesday preceding 21 September (St Mathew’s Day.[16] The purpose was to separate the date of the fair from the usual rental quarter day which enabled the trustees to lease the fair as a separate item.

The family of William Mizen tenanted the right to the fair from 1841 at an annual rent of £10 on a yearly tenancy.[17] It wasn’t a success and in 1858 the Northey family took back the tenancy with claims that the yearly value was above £25.

It is not clear why Rev Alfred Edward, the oldest surviving son of William Brook Northey, didn’t take up the Box joint lordship on his father’s death in 1880, Instead the tenure passed as a joint tenancy to the two eldest sons of Col Edward Richard Northey - Rev Edward William and George Wilbraham.

These men held the lordship of Box jointly. They were both military men, serving abroad for considerable periods but they were very different in personality. Colonel Edward Richard (1795 - 1878) served with 52nd Light Infantry in Napoleonic Wars ending at the Battle of Waterloo. He was present throughout the Peninsula War including the 1812 Battle of Vitoria, Spain, when Wellington's troops defeated Joseph Bonaparte. It was a decisive moment in the Peninsula War and was recalled in the book Sharpe's Honour. At the battle, Sir Harry Smith told the story of how Edward Richard was knocked down by the wind of his shot and his face as black as if he had been two hours in a pugilistic ring.[10] On his return to England Edward Richard married Charlotte Anson in 1828. More family Christian names derive from this generation, including Anson and Charlotte's brother-in-law was Edward Bootle-Wilbraham (later Baron Skelmersdale). Col Edward Richard used Woodcote, Surrey, as his main home in the UK, which he inherited personally on the death of his father in 1828 but it was his second son who eventually made Box his home.

William Brook Northey, brother of Col Edward Richard, was also a military man (the Coldstream Guards) but, in contrast, was more involved in the village, often in the minutiae of arrangements. On 21 October 1842 at the Chequers Pub, William Brook was instrumental in forming a new Oddfellows Lodge in Box, called after him as the Loyal Northey Lodge. About 40 gentlemen sat down to entertainment, food and wine which reflected the highest credit on the taste and liberality of the host, Mr Vezey.[11] It was a significant development whose purpose was to support members with provision against sickness, death and usual misfortune. The lodge was actively involved in village life, for many decades running an annual fete at Fete Field (now Bargates) along with the Foresters and the Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes. The fete only ceased totally after the Second World War.

There were a number of significant gifts of land to the village during the trustees’ joint tenure of the estates. After the tragic death of the vicar’s wife Elizabeth Horlock and sister-in-law Alice Suddell in 1858, they gifted land for the building of Box Cemetery at the instigation of the estate solicitor Mr Mant.[12] It was a significant act of generosity, in some ways the epitaph of Mr Mant, the long-serving legal agent of the family in Box who died later that year and was succeeded by William Adair Bruce.[13] The same generosity was evident in the 1870s when the trustees gave land for the building of the Box Schools in 1875 and installed a water supply to the east of the village which flowed into the Poynder Fountain as well as the properties which developed on this side of Box.

We get some idea of the difficulty in funding the estate from contemporary snippets of information. With farming under increasing financial pressure in 1843, ten percent of the half-year’s rent was returned to tenants by ER and WB Northey.[14] Around this time the trustees sought alternative fundraising methods with the Kingsdown Fair, said to be not a fair in the legal sense of the word or in any way an incorporeal hereditament but simply the occupation of Kingsdown for several consecutive days for a horse, sheep and other cattle fair, the animals being placed in pens on the down and payments being thereupon made for pens etc.[15]

In 1840 they changed the date of Kingsdown Fair from Michaelmas (29 September) to roughly a fortnight earlier, to be held 16 September in 1840 and thereafter the first Wednesday preceding 21 September (St Mathew’s Day.[16] The purpose was to separate the date of the fair from the usual rental quarter day which enabled the trustees to lease the fair as a separate item.

The family of William Mizen tenanted the right to the fair from 1841 at an annual rent of £10 on a yearly tenancy.[17] It wasn’t a success and in 1858 the Northey family took back the tenancy with claims that the yearly value was above £25.

It is not clear why Rev Alfred Edward, the oldest surviving son of William Brook Northey, didn’t take up the Box joint lordship on his father’s death in 1880, Instead the tenure passed as a joint tenancy to the two eldest sons of Col Edward Richard Northey - Rev Edward William and George Wilbraham.

Changing Times

We can see from the long tenure of ER and WB Northey from 1826 until 1878 that society was changing in the early Victorian period. The period started with largely manual farming methods in Box, even using medieval ox-drawn ploughs at times. In 1849 The Bath & West annual ploughing match was held in a clover ley owned by Captain ER Northey and tenanted by William Brown at Hazelbury.[18] The event attracted 42 ploughs competing, the majority drawn by pairs of horses. There were a few with oxen, two abreast, and one with oxen single-harnessed. Captain Northey wasn’t present, the chair taken by Major Pickwick and Rev Horlock doing the toasting. By 1864 the concept of agricultural competitions had shifted and the third annual Box Horticultural and Floral Society Show was held at Mr Pinchen’s farm for flowers, fruit and vegetables with classes open to cottagers and tenants. At a similar time the annual ploughing match was held at Bovils, near the Swan Inn on Ashley Farm.[19]

Leading the economic changes in Box was the railway, symbolic of which was the replacement of the old Cuttings Mill with the new Box Railway Station in 1841. Rail travel also greatly affected the road structure. In 1849 two leasehold cottages owned by the trustees were sold. They were situated on Box Hill, fronting the Turnpike Road leading from Box to Corsham one of which was in the occupation of George Dagger, the other empty.[20] The properties were said to be in good repair.

In some respects, the changes were the precursor to the enormous shifts witnessed in the late Victorian period in the village under George Wilbraham Northey of Box, whose story and that of his family are told later in this series.

We can see from the long tenure of ER and WB Northey from 1826 until 1878 that society was changing in the early Victorian period. The period started with largely manual farming methods in Box, even using medieval ox-drawn ploughs at times. In 1849 The Bath & West annual ploughing match was held in a clover ley owned by Captain ER Northey and tenanted by William Brown at Hazelbury.[18] The event attracted 42 ploughs competing, the majority drawn by pairs of horses. There were a few with oxen, two abreast, and one with oxen single-harnessed. Captain Northey wasn’t present, the chair taken by Major Pickwick and Rev Horlock doing the toasting. By 1864 the concept of agricultural competitions had shifted and the third annual Box Horticultural and Floral Society Show was held at Mr Pinchen’s farm for flowers, fruit and vegetables with classes open to cottagers and tenants. At a similar time the annual ploughing match was held at Bovils, near the Swan Inn on Ashley Farm.[19]

Leading the economic changes in Box was the railway, symbolic of which was the replacement of the old Cuttings Mill with the new Box Railway Station in 1841. Rail travel also greatly affected the road structure. In 1849 two leasehold cottages owned by the trustees were sold. They were situated on Box Hill, fronting the Turnpike Road leading from Box to Corsham one of which was in the occupation of George Dagger, the other empty.[20] The properties were said to be in good repair.

In some respects, the changes were the precursor to the enormous shifts witnessed in the late Victorian period in the village under George Wilbraham Northey of Box, whose story and that of his family are told later in this series.

References

[1] For the Epsom story and much of the autobiographical information here, please see the marvellous website written by

Linda Jackson: epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/Northeys0.html

[2] Copy Deed, Wiltshire History Society, 727/3/10. Queen Anne's Bounty was a national scheme of 1704 to augment the income of poorer clergymen by reallocating certain income to them rather than to the crown.

[3] The property was inherited by Northey's son who eventually sold it to Matthew Humphreys, a Chippenham Clothier, in 1791.

[4] Check out Phil's wonderful photos of St Thomas a Becket with 33 photos of the church at:

www.flickr.com/photos/churchcrawler/albums/72157623765890496

[5] https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/northey-william-1753-1826

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 27 July 1780

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 1 July 1790

[8] The National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/1177/19

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 26 February 1789

[10] Private Notes held by Northey Family

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 3 November 1842

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 21 January 1858

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 16 November 1843

[15] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[16] The Bath Chronicle, 27 August 1840

[17] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[18] The Bath Chronicle, 27 September 1949

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 25 August 1864

[20] The Bath Chronicle, 1 November 1949

[1] For the Epsom story and much of the autobiographical information here, please see the marvellous website written by

Linda Jackson: epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/Northeys0.html

[2] Copy Deed, Wiltshire History Society, 727/3/10. Queen Anne's Bounty was a national scheme of 1704 to augment the income of poorer clergymen by reallocating certain income to them rather than to the crown.

[3] The property was inherited by Northey's son who eventually sold it to Matthew Humphreys, a Chippenham Clothier, in 1791.

[4] Check out Phil's wonderful photos of St Thomas a Becket with 33 photos of the church at:

www.flickr.com/photos/churchcrawler/albums/72157623765890496

[5] https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/northey-william-1753-1826

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 27 July 1780

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 1 July 1790

[8] The National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/1177/19

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 26 February 1789

[10] Private Notes held by Northey Family

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 3 November 1842

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 21 January 1858

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 16 November 1843

[15] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[16] The Bath Chronicle, 27 August 1840

[17] The Bath Chronicle, 17 January 1861

[18] The Bath Chronicle, 27 September 1949

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 25 August 1864

[20] The Bath Chronicle, 1 November 1949