Drove Roads in Box Alan Payne April 2023

It is usually claimed that drove routes were part of a national network of paths for herding animals to market, most notably travelling from South Wales to London. But the evidence is sometimes confused with a semi-fictional, romanticised view of an idyllic, past rural life in the English countryside. Virtually all rural roads probably started as drove routes as the main purpose of country roads was to take livestock to market and bring back implements and young animals. The routes we call byways, bridleways, green lanes and droveways might simply be roads which were never tarmac’d or improved – as unprovable as salt roads, packhorse tracks and prehistoric ridgeways. Similarly, Henley Lane was previously known as Green Lane, still remembered in the name Green Lane Farm but there is no evidence that it was ever a droving route. So, the basis of this article is to consider if any real drovers’ routes can be identified in Box.

The two roads above are within a few yards of each other and probably started out similarly. The one on the left is the Drilley, reputed to be the original access to Hatt House . The road was never improved and is now a sunken greenway. The one on the right is Short Hill, later tarmac'd and now a busy highway.

(Photos courtesy Carol Payne)

(Photos courtesy Carol Payne)

Evidence of Droving in Box

It has been claimed that drove routes existed for thousands of years from the Iron Age until the Second World War, although their prominence became more significant in the medieval to Victorian period.[1] This doesn’t mean that the same routes were used throughout the period and paths often changed due to obstacles, road improvements and topographical alterations.

The difficulty is compounded because authentication for drove routes usually comes from flimsy contemporary evidence of local placenames and verge widths.

We get an interesting contemporary description of a local drover’s life from a 1931 prosecution of animal cruelty when a wounded animal was herded on the public highway.[2] In that year Edgar Mounty, a cattle drover of The Conigre, Trowbridge, was paid to herd 17 Irish cattle from Trowbridge Market to Box Hill. One heifer sustained a wound on her fetlock at Woolley Park and was bleeding severely. Mounty was refused shelter by nearby farmers and some of the herd escaped onto a private lawn. Mounty eventually released the animals to graze at the side of the road at Bradford Leigh, where he was caught by the police. Mounty said he had been a drover all his life and did not like to travel too fast as it wore his boots out. He had a wife and six little children to support. The case was dismissed.

Probably this description of a drover’s life was closer to the truth than a romanticised portrayal of drovers as a cheerful, civil and gay lot of fellows.[3] The drovers were often subject to legislation because of the huge value of the herds they controlled.

Acts of Parliament were passed between 1562 and 1603 to licence drovers who could prove their social standing. About this time, drovers became responsible for bank transmissions when cash was converted into animals at the outset of routes and redeemed at the destination market. This was considered much safer than carrying money on horseback, which was liable to attack by highwaymen. But animal droves were prone to losses on route, involving rustling, deaths and reduction of the animals’ weight - all of which affected the consequent market value of the drove. How could sellers know that the drover was honest?

To deter rogues in the trade, drovers were subjected to strenuous bankruptcy laws in 1705 in the reign of Queen Anne. It seems to have worked as the reputation of drovers remained high. Following the accession of the Hanoverian dynasty with George I, there was an upsurge of Jacobite insurrection and a curtailment of the right to carry weapons. The drovers were considered sufficiently respectable to be exempted from the ban on carrying arms between 1716 and 1748.

It has been claimed that drove routes existed for thousands of years from the Iron Age until the Second World War, although their prominence became more significant in the medieval to Victorian period.[1] This doesn’t mean that the same routes were used throughout the period and paths often changed due to obstacles, road improvements and topographical alterations.

The difficulty is compounded because authentication for drove routes usually comes from flimsy contemporary evidence of local placenames and verge widths.

We get an interesting contemporary description of a local drover’s life from a 1931 prosecution of animal cruelty when a wounded animal was herded on the public highway.[2] In that year Edgar Mounty, a cattle drover of The Conigre, Trowbridge, was paid to herd 17 Irish cattle from Trowbridge Market to Box Hill. One heifer sustained a wound on her fetlock at Woolley Park and was bleeding severely. Mounty was refused shelter by nearby farmers and some of the herd escaped onto a private lawn. Mounty eventually released the animals to graze at the side of the road at Bradford Leigh, where he was caught by the police. Mounty said he had been a drover all his life and did not like to travel too fast as it wore his boots out. He had a wife and six little children to support. The case was dismissed.

Probably this description of a drover’s life was closer to the truth than a romanticised portrayal of drovers as a cheerful, civil and gay lot of fellows.[3] The drovers were often subject to legislation because of the huge value of the herds they controlled.

Acts of Parliament were passed between 1562 and 1603 to licence drovers who could prove their social standing. About this time, drovers became responsible for bank transmissions when cash was converted into animals at the outset of routes and redeemed at the destination market. This was considered much safer than carrying money on horseback, which was liable to attack by highwaymen. But animal droves were prone to losses on route, involving rustling, deaths and reduction of the animals’ weight - all of which affected the consequent market value of the drove. How could sellers know that the drover was honest?

To deter rogues in the trade, drovers were subjected to strenuous bankruptcy laws in 1705 in the reign of Queen Anne. It seems to have worked as the reputation of drovers remained high. Following the accession of the Hanoverian dynasty with George I, there was an upsurge of Jacobite insurrection and a curtailment of the right to carry weapons. The drovers were considered sufficiently respectable to be exempted from the ban on carrying arms between 1716 and 1748.

Kingsdown Common Area

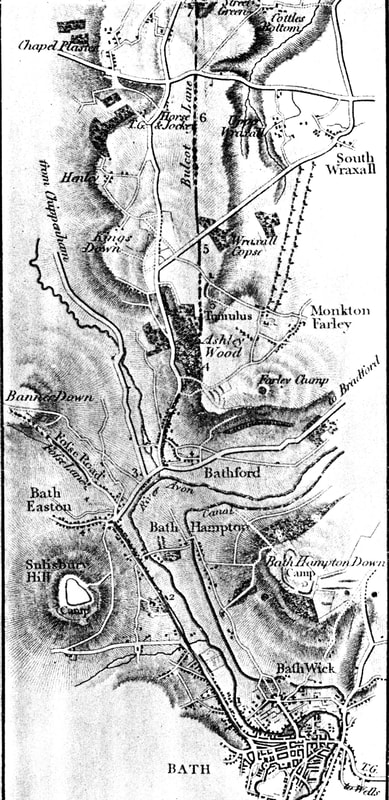

The best analysis of drove routes in our area comes from Devizes man, Ken Watts.[4] He recorded that few drove roads passed through the village. The usual South Wales drove route for black cattle went north of Box through Gloucestershire via Malmesbury to Chippenham. Another route went south through Salisbury.[5] But he claims that there is evidence of two droving routes in the parish: around Kingsdown Common and another close to Blue Vein.

According to Ken Watts, one route probably came from Monkton Farleigh then along Link Lane (a significant name) to Kingsdown Common and then along the old Roman road (still the south boundary of the parish). The roads around Kingsdown Common and Longsplatt meet the criteria, having unusually wide verges suitable for grazing animals. The width of the verges on the highways around Longsplatt (see headline picture) make little sense if not as a wayside verge for animals. The width of this road clearly predated the use of the route for stone-quarry carts when the area was quarried by the Northey Stone Quarry Company from 1893 until 1913. Ken Watts pointed out that the area called The Closes may have referred to drove closes beside the Common. But equally, this could be a reference to holding areas for animals awaiting the fair and we have to be cautious because the Kingsdown Sheep Fair only started in 1798.

The best analysis of drove routes in our area comes from Devizes man, Ken Watts.[4] He recorded that few drove roads passed through the village. The usual South Wales drove route for black cattle went north of Box through Gloucestershire via Malmesbury to Chippenham. Another route went south through Salisbury.[5] But he claims that there is evidence of two droving routes in the parish: around Kingsdown Common and another close to Blue Vein.

According to Ken Watts, one route probably came from Monkton Farleigh then along Link Lane (a significant name) to Kingsdown Common and then along the old Roman road (still the south boundary of the parish). The roads around Kingsdown Common and Longsplatt meet the criteria, having unusually wide verges suitable for grazing animals. The width of the verges on the highways around Longsplatt (see headline picture) make little sense if not as a wayside verge for animals. The width of this road clearly predated the use of the route for stone-quarry carts when the area was quarried by the Northey Stone Quarry Company from 1893 until 1913. Ken Watts pointed out that the area called The Closes may have referred to drove closes beside the Common. But equally, this could be a reference to holding areas for animals awaiting the fair and we have to be cautious because the Kingsdown Sheep Fair only started in 1798.

|

Placename evidence is extremely difficult to prove and continuity of names is very uncertain. For example, Bull Lane in the centre of Box, seems to be a twentieth century invention without any historic relevance. But there are other placename references in the areas around Kingsdown Common which support evidence of droving. The name Longsplatt may itself refer to droving. Traditionally the description Long Acre referred to areas around holding paddocks where drovers could tether animals on the grass verge awaiting the opportunity to move on. The other part of the name is a variation of the word splatt meaning an unclaimed plot of land (compare Mills Splatt).

The route alongside the Roman road is shown as a definite road on the map by Andrews & Drury, eventually going via Atworth and Whitley Common to Lacock.[6] This track was given the name Bulcot Lane by Sir Richard Colt-Hoare when he visited the area in October 1819: We noticed a trench cut on the South side of the road almost wide enough to admit a cart, which cavity is denominated Bulcot Lane... We walked along Bulcot Lane (or trench, to the South of it), where we met with some large stones fallen into the trench, which seemed to corroborate our former opinion, that they had originally formed the lower stratum of the causeway... The Roman way is now crossed by a modern road from Corsham to South Wraxall, at the extremity of Bulcot Lane. Left: Sir Richard Colt Hoare, The Ancient History of Wiltshire. reprinted 1975 EP Publishing Limited, p.7 and 77 |

Blue Vein Drove Route

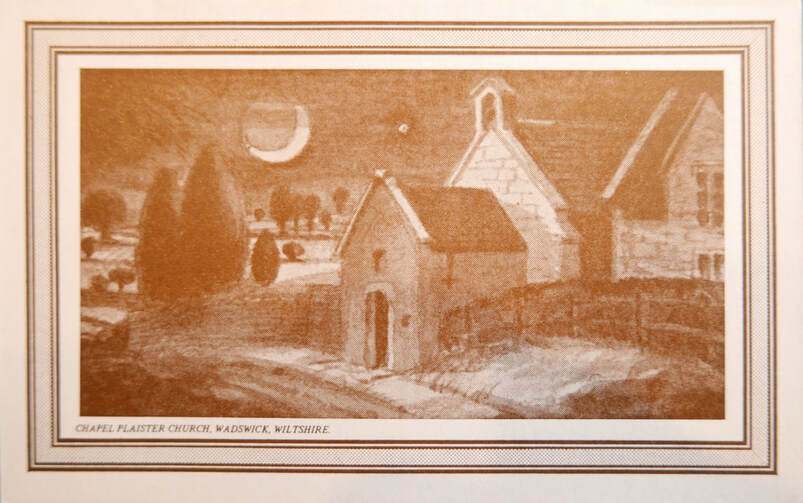

Ken Watts recorded that an alternative drove route went along the medieval ridgeway track past Blue Vein turnpike and through to Chapel Plaister, Wadswick, to Neston.[7] He also claims that the road from Chapel Plaister running south to Bradford Leigh resembles a droveway.

Ken Watts recorded that an alternative drove route went along the medieval ridgeway track past Blue Vein turnpike and through to Chapel Plaister, Wadswick, to Neston.[7] He also claims that the road from Chapel Plaister running south to Bradford Leigh resembles a droveway.

Further Evidence

To make them viable, drove roads clearly need entrance and exit routes. There is anecdotal evidence of a drovers' road running into the centre of Box at Ashley. Grey Tiles reputedly has a freshwater pond below it which may have been used to water animals. It may have joined up with Wormcliffe Lane, possibly a pilgrims' way into Bath.

There are several roads running off of the medieval ridgeway at the Old Jockey area, including the Bradford Road and the path from Hatt Farm up to Chapel Plaister called Short Hill by locals. The road between the Chapel and Fiveways has a remarkable width, double that of a modern highway. More intriguingly, the track next to Blue Vein Tollhouse appears to have been used to avoid tolls on the ridgeway route. This may well have been used for animal movement off Kingsdown Common (although it has also been stated that this track was simply the main entrance route to Hatt House, via Keeper’s Cottage). Having herded the animals to Wadswick Common via one or other of these two routes, we can then speculate that the drovers took the path through Wadswick, where tradition has it that the wayside pool is further evidence of droving.

To make them viable, drove roads clearly need entrance and exit routes. There is anecdotal evidence of a drovers' road running into the centre of Box at Ashley. Grey Tiles reputedly has a freshwater pond below it which may have been used to water animals. It may have joined up with Wormcliffe Lane, possibly a pilgrims' way into Bath.

There are several roads running off of the medieval ridgeway at the Old Jockey area, including the Bradford Road and the path from Hatt Farm up to Chapel Plaister called Short Hill by locals. The road between the Chapel and Fiveways has a remarkable width, double that of a modern highway. More intriguingly, the track next to Blue Vein Tollhouse appears to have been used to avoid tolls on the ridgeway route. This may well have been used for animal movement off Kingsdown Common (although it has also been stated that this track was simply the main entrance route to Hatt House, via Keeper’s Cottage). Having herded the animals to Wadswick Common via one or other of these two routes, we can then speculate that the drovers took the path through Wadswick, where tradition has it that the wayside pool is further evidence of droving.

Big Pool Lane

A local resident, Robin Bullock, told me that a route on the Amazon delivery planner was called Big Pool Lane but he had never been able to find it. The name sounded like a potential droving route, used to bypass tolls gates and offering a watering hole for animals. So it was obviously worth investigating.

A local resident, Robin Bullock, told me that a route on the Amazon delivery planner was called Big Pool Lane but he had never been able to find it. The name sounded like a potential droving route, used to bypass tolls gates and offering a watering hole for animals. So it was obviously worth investigating.

The first possibility is a footpath running from opposite Ashley Barn up to Lower Kingsdown Road. It appears as a stream in Allen's 1626 map and is still marked as a parish footpath. There is a reference in 1895 that the path was in regular use (needing a county surveyor to inspect).[8] The pool as such still existed in 1933 when unemployed men were engaged to clear it out.[9] The name continued after the Second World War and its condition investigated in 1945.[10]

The second possibility is slightly further up Wormcliffe Lane, and perhaps the more likely path. It runs from opposite Hunters and comes out close to the closure of Lower Kingsdown Road. This has all the right attributes for a droving route: sunked path indicating substantial use and a constant stream even in the driest of seasons. The pool presumably lay to the foot of the hillside but appears to have been silted up now.

The second possibility is slightly further up Wormcliffe Lane, and perhaps the more likely path. It runs from opposite Hunters and comes out close to the closure of Lower Kingsdown Road. This has all the right attributes for a droving route: sunked path indicating substantial use and a constant stream even in the driest of seasons. The pool presumably lay to the foot of the hillside but appears to have been silted up now.

These photos of the second possibility show the likely appearance of Big Pool Lane in its prime: left Lower Kingsdown Road; middle the descent down the lane; right the water that runs continuously at the foot (courtesy Carol Payne)

Scots Pine Indicators

There have been several twentieth century writers who claim that references to clumps of Scots Pine trees are indicators of drovers’ inns, a marker to show travellers that they could find accommodation and refreshment close to enclosures for animals.[11] Chapel Plaister used to be marked with two clumps of Scots Pine trees, some to the right of the Hazelbury entrance drive and others in the gardens of the cottages opposite the Chapel. People refer to the use of The Bell Inn next door to Chapel Plaister as further evidence.

There have been several twentieth century writers who claim that references to clumps of Scots Pine trees are indicators of drovers’ inns, a marker to show travellers that they could find accommodation and refreshment close to enclosures for animals.[11] Chapel Plaister used to be marked with two clumps of Scots Pine trees, some to the right of the Hazelbury entrance drive and others in the gardens of the cottages opposite the Chapel. People refer to the use of The Bell Inn next door to Chapel Plaister as further evidence.

In the 1980s (when we first moved to the area) clumps of Scots Pine trees stood at the corner of the Kingsdown and Monkton Farleigh Roads, just up from the Swan Inn. These have now all disappeared.

Conclusion

It is hard to pick out fact from fiction in tracing old drove roads. Nonetheless, the coincidence of evidence is substantial around Kingsdown Common and along the roads going to Wadswick: place names, track widths and road continuations are a compelling combination of drovers’ routes in the area. Can any reader help with more evidence of droving in Box please?

It is hard to pick out fact from fiction in tracing old drove roads. Nonetheless, the coincidence of evidence is substantial around Kingsdown Common and along the roads going to Wadswick: place names, track widths and road continuations are a compelling combination of drovers’ routes in the area. Can any reader help with more evidence of droving in Box please?

References

[1] Francis Pryor, The Making of the British Landscape, 2011, Penguin Books

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 30 May 1931

[3] RH Wilson, The Sparrow Hunters, 1975, Shrivenhan Heritage Society

[4] KG Watts, Droving in Wiltshire, 1990, The Wiltshire Life Society

[5] KG Watts, Droving in Wiltshire, 1990, The Wiltshire Life Society, p.75

[6] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 8, 1952

[7] KG Watts, Droving in Wiltshire, 1990, The Wiltshire Life Society, p.76

[8] Bristol Mercury, 19 November 1895

[9] Bath Chronicle, 2 December 1933

[10] The Wiltshire Times, 6 January 1945

[11] KG Watts, Droving in Wiltshire, 1990, The Wiltshire Life Society, p.90

[1] Francis Pryor, The Making of the British Landscape, 2011, Penguin Books

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 30 May 1931

[3] RH Wilson, The Sparrow Hunters, 1975, Shrivenhan Heritage Society

[4] KG Watts, Droving in Wiltshire, 1990, The Wiltshire Life Society

[5] KG Watts, Droving in Wiltshire, 1990, The Wiltshire Life Society, p.75

[6] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 8, 1952

[7] KG Watts, Droving in Wiltshire, 1990, The Wiltshire Life Society, p.76

[8] Bristol Mercury, 19 November 1895

[9] Bath Chronicle, 2 December 1933

[10] The Wiltshire Times, 6 January 1945

[11] KG Watts, Droving in Wiltshire, 1990, The Wiltshire Life Society, p.90