Building a New Society Alan Payne September 2022

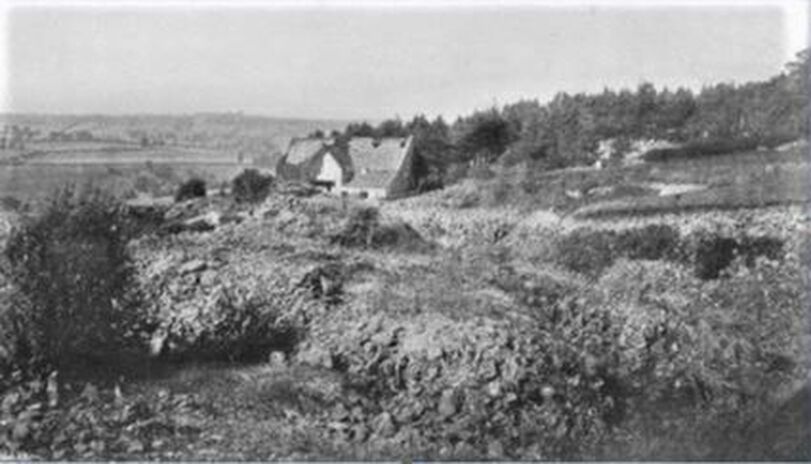

We rightly discuss the need for affordable, decent houses in Britain today but that problem isn’t new; it existed throughout the first part of the twentieth century. The issue now is to have more houses but in the inter-war years there was a need to modernise poor quality houses to reduce overcrowding. Part of the problem was the amount of privately-owned rental property, estimated to be the housing status of 90% of the population in 1914. These properties were often allowed to deteriorate by landlords with little incentive to improve them when rents could not be raised in the middle of recession. It was an issue that was understood in Box in the 1930s with both private and council rebuilding initiatives.

Housing in Box

The 1919 sale particulars of the properties owned by the Noble family tells us much about the condition of houses in Box after the Great War: Frogmore House and shop in the Market Place contained 9 rooms and offices, sales shop and 2 store rooms over .. now let at a reduced rental of £21 (worth today £1,200 a year). Four cottages adjoining at the Year Rentals of £7 (today £400 a year).[1] The 8 stone-built cottages at Townsend were let on a term of 840 years from 1827 .. (Ground) Rent of £1.

The Northey Estate Sales of 1919 and 1923 were similarly disappointing. Many of the properties didn’t sell at auction and others were lowly priced. The Hermitage was described as a comfortable, old-fashioned residence, lift (presumably a dumbwaiter) from kitchen and speaking tube) and even though it had hot and cold running water and an internal lavatory, it sold for only £1,300 (today worth £75,000). The Manor Farm didn’t sell, several of the smaller cottages weren’t affordable by the tenants and their tenure severely reduced the commercial attractiveness for investors. In the end, purchases were given the option of paying by instalments over a 10-year period plus interest.[2] It all seems ridiculous today and those who took the risk became wealthy, including Fred Neate at Box Hill. There were many reasons for these problems in residential housing, not just poor quality of housing and the inability of tenants to pay higher rents.

The Law of Property Acts in the 1920s sought to redefine and simplify how land was held, both tenancies and landowners.

The 1922 Act consolidated types of tenure into a term of years absolute, abolishing copyhold and customary tenures and redefining special tenures (fee tail giving rights to pass property to heirs, life estate giving rights for the tenant’s life only,

per autre someone else’s life, usually child). The 1925 Act simplified landlord ownership as freehold under the definition fee, simple, absolute in possession (meaning inheritance of sub-tenures, freedom to leave property in a will, everlasting, with the right to occupy or take rent). By simplifying property rights into freehold and tenancy, the watering down of rental income made rents a more attractive proposition).

Changes in Government Responsibilities

The Ministry of Reconstruction was formed in 1919 to achieve Lloyd George’s slogan of Homes Fit for Heroes after the First World War. It proved to be rather an empty pledge, especially in the north of England, but the Housing Act of 1919 encouraged private builders by authorising local authorities to grant subsidies to them, which opened up the possibility of home ownership for working class people. The initiative was changed shortly afterwards by the 1924 Housing Act which promoted council houses for rent as well as an expansion of private ownership. This boosted the Bath Liberal Permanent Mutual Building Society (named permanent to encourage new members, not just replacements as members died, common in the old Friendly Societies). A number of Box residents took advantage of mortgages to buy their house, such as Edwin William Eyles, bootmaker, who took a mortgage of £175 with the society in June 1919 to buy his residence at South View, Quarry Hill.

These changes demonstrated an end of the old laissez faire philosophy, in which the main roles of government were foreign diplomacy and war. Increasingly, governments of all political persuasion wrestled with problems of welfare, unemployment, health, education, housing and the great structural problems of recession and economic stagnation. In the 1920s the role of local authorities was still evolving having only been in operation for twenty years, several of which had concentrated on wartime issues not public services. Local councils had a considerable income from rates but the task of paying unemployment and poor relief was so great that additional government grants were needed. Gradually central government took control of the dole payments through labour exchanges (employment agencies), means tests (assessments of eligibility to state aid) and the reduction of unemployment payments after 1931.

Private House Building after 1919

When the Box Parish Council was established in 1895, their civil jurisdiction covered the areas of Ditteridge and Box Parish Churches. The two areas were amalgamated because Ditteridge had less than 300 electors and both could then be considered in the same rural council sanitary area, North Wiltshire (then called either Chippenham or Calne and District). Considerable authority was allocated to the councils. The Ministry of Health Act of 1919 formalised government responsibility for public health, midwifery, poor law administration and abolished local government boards responsible for social and welfare administration. The abolition of the Poor Law in 1929 was the final end of the parochial system of support, which had once been characterised by Box’s Poorhouse in Church Lane.

There was a dramatic increase in Box residential development with infill, private house-building, most of which sold for £450.

A local Box firm T&E Best bought a parcel of land on the east side of the village from the Northey family in 1927 and got piecemeal planning permission for the bungalows that we know as The Bassetts.[3] In 1928 five bungalows were planned and in 1929 an unspecified number of additional ones.[4] The firm was ideal to develop the site because Thomas Charles Best

(22 March 1888-1954) and his wife and business partner Florence Elsie (b 27 January 1893-2 February 1959) lived in the property they built at Number 1, The Bassetts, sometimes called Oak House.[5] The houses they constructed were well-built with four or five rooms, a kitchenette, bathroom and, unusually for the older houses in the village, connected with the utilities of gas, water and mains drainage.[6]

Housing in Box

The 1919 sale particulars of the properties owned by the Noble family tells us much about the condition of houses in Box after the Great War: Frogmore House and shop in the Market Place contained 9 rooms and offices, sales shop and 2 store rooms over .. now let at a reduced rental of £21 (worth today £1,200 a year). Four cottages adjoining at the Year Rentals of £7 (today £400 a year).[1] The 8 stone-built cottages at Townsend were let on a term of 840 years from 1827 .. (Ground) Rent of £1.

The Northey Estate Sales of 1919 and 1923 were similarly disappointing. Many of the properties didn’t sell at auction and others were lowly priced. The Hermitage was described as a comfortable, old-fashioned residence, lift (presumably a dumbwaiter) from kitchen and speaking tube) and even though it had hot and cold running water and an internal lavatory, it sold for only £1,300 (today worth £75,000). The Manor Farm didn’t sell, several of the smaller cottages weren’t affordable by the tenants and their tenure severely reduced the commercial attractiveness for investors. In the end, purchases were given the option of paying by instalments over a 10-year period plus interest.[2] It all seems ridiculous today and those who took the risk became wealthy, including Fred Neate at Box Hill. There were many reasons for these problems in residential housing, not just poor quality of housing and the inability of tenants to pay higher rents.

The Law of Property Acts in the 1920s sought to redefine and simplify how land was held, both tenancies and landowners.

The 1922 Act consolidated types of tenure into a term of years absolute, abolishing copyhold and customary tenures and redefining special tenures (fee tail giving rights to pass property to heirs, life estate giving rights for the tenant’s life only,

per autre someone else’s life, usually child). The 1925 Act simplified landlord ownership as freehold under the definition fee, simple, absolute in possession (meaning inheritance of sub-tenures, freedom to leave property in a will, everlasting, with the right to occupy or take rent). By simplifying property rights into freehold and tenancy, the watering down of rental income made rents a more attractive proposition).

Changes in Government Responsibilities

The Ministry of Reconstruction was formed in 1919 to achieve Lloyd George’s slogan of Homes Fit for Heroes after the First World War. It proved to be rather an empty pledge, especially in the north of England, but the Housing Act of 1919 encouraged private builders by authorising local authorities to grant subsidies to them, which opened up the possibility of home ownership for working class people. The initiative was changed shortly afterwards by the 1924 Housing Act which promoted council houses for rent as well as an expansion of private ownership. This boosted the Bath Liberal Permanent Mutual Building Society (named permanent to encourage new members, not just replacements as members died, common in the old Friendly Societies). A number of Box residents took advantage of mortgages to buy their house, such as Edwin William Eyles, bootmaker, who took a mortgage of £175 with the society in June 1919 to buy his residence at South View, Quarry Hill.

These changes demonstrated an end of the old laissez faire philosophy, in which the main roles of government were foreign diplomacy and war. Increasingly, governments of all political persuasion wrestled with problems of welfare, unemployment, health, education, housing and the great structural problems of recession and economic stagnation. In the 1920s the role of local authorities was still evolving having only been in operation for twenty years, several of which had concentrated on wartime issues not public services. Local councils had a considerable income from rates but the task of paying unemployment and poor relief was so great that additional government grants were needed. Gradually central government took control of the dole payments through labour exchanges (employment agencies), means tests (assessments of eligibility to state aid) and the reduction of unemployment payments after 1931.

Private House Building after 1919

When the Box Parish Council was established in 1895, their civil jurisdiction covered the areas of Ditteridge and Box Parish Churches. The two areas were amalgamated because Ditteridge had less than 300 electors and both could then be considered in the same rural council sanitary area, North Wiltshire (then called either Chippenham or Calne and District). Considerable authority was allocated to the councils. The Ministry of Health Act of 1919 formalised government responsibility for public health, midwifery, poor law administration and abolished local government boards responsible for social and welfare administration. The abolition of the Poor Law in 1929 was the final end of the parochial system of support, which had once been characterised by Box’s Poorhouse in Church Lane.

There was a dramatic increase in Box residential development with infill, private house-building, most of which sold for £450.

A local Box firm T&E Best bought a parcel of land on the east side of the village from the Northey family in 1927 and got piecemeal planning permission for the bungalows that we know as The Bassetts.[3] In 1928 five bungalows were planned and in 1929 an unspecified number of additional ones.[4] The firm was ideal to develop the site because Thomas Charles Best

(22 March 1888-1954) and his wife and business partner Florence Elsie (b 27 January 1893-2 February 1959) lived in the property they built at Number 1, The Bassetts, sometimes called Oak House.[5] The houses they constructed were well-built with four or five rooms, a kitchenette, bathroom and, unusually for the older houses in the village, connected with the utilities of gas, water and mains drainage.[6]

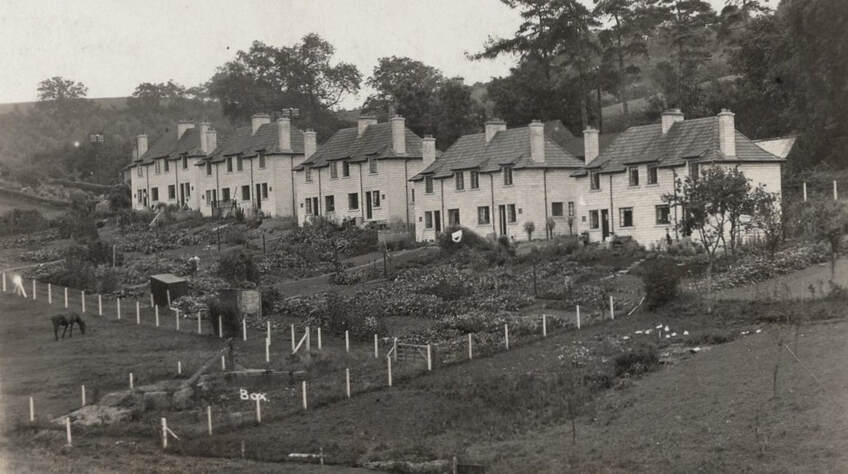

Council Houses after 1924

In 1928 the Housing Committee of the Rural District Council formulated its plans for awarding council tenancies in Box and Corsham: to ex-servicemen, large families and good payers.[7] Tenants were not permitted to build outhouses or to sub-let and rents were fixed at 5s.3d per week (26p in decimal currency). Nothing came of the proposals for a couple of years despite a long search for suitable land in Box.

The Housing Act of 1930 extended grants to local councils for slum clearance and rebuilding where there was an acute shortage. This was the incentive that the local authorities needed and several ranks of council houses were planned. The council houses eventually built in Box were at one side of Barn Piece (1931) and The Ley (1938, built by builders T Merrett & Son of Bourton House, Box).[8] But at this point the initiative came to an end in Box and most of the other council houses in the village were created post-war, including Bargates and Brunel Way (both 1951), Ben Cross (1954) and Hazelbury Hill (1954).[9]

In 1928 the Housing Committee of the Rural District Council formulated its plans for awarding council tenancies in Box and Corsham: to ex-servicemen, large families and good payers.[7] Tenants were not permitted to build outhouses or to sub-let and rents were fixed at 5s.3d per week (26p in decimal currency). Nothing came of the proposals for a couple of years despite a long search for suitable land in Box.

The Housing Act of 1930 extended grants to local councils for slum clearance and rebuilding where there was an acute shortage. This was the incentive that the local authorities needed and several ranks of council houses were planned. The council houses eventually built in Box were at one side of Barn Piece (1931) and The Ley (1938, built by builders T Merrett & Son of Bourton House, Box).[8] But at this point the initiative came to an end in Box and most of the other council houses in the village were created post-war, including Bargates and Brunel Way (both 1951), Ben Cross (1954) and Hazelbury Hill (1954).[9]

Conclusion

By 1939 over 4 million new homes had been built in Britain in the two decades since 1920. Many of these were new, suburban developments, with individual houses sometimes characterised by mock Tudor fronts in wealthy areas. This was not the case in Box, where most new housing was terraced and semi-detached, well-built council houses of uniform design.

There was, however, another significant change in housing stock in Box. The economic boom of the late 1930s and the expansion of low interest rates encouraged a huge increase in property ownership which rose from 10% in 1914 to 31% by 1939. The continuing sale of private land plots by the Northey Estate led to a huge increase in owner occupied houses, often built by local stone masons.

By 1939 over 4 million new homes had been built in Britain in the two decades since 1920. Many of these were new, suburban developments, with individual houses sometimes characterised by mock Tudor fronts in wealthy areas. This was not the case in Box, where most new housing was terraced and semi-detached, well-built council houses of uniform design.

There was, however, another significant change in housing stock in Box. The economic boom of the late 1930s and the expansion of low interest rates encouraged a huge increase in property ownership which rose from 10% in 1914 to 31% by 1939. The continuing sale of private land plots by the Northey Estate led to a huge increase in owner occupied houses, often built by local stone masons.

References

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 18 October 1919

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 2 June 1923

[3] Courtesy Stella Clarke

[4] North Wilts Herald, 20 April 1928 and The Wiltshire Times, 10 August 1929

[5] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 1 September 1928

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 25 April 1931

[7] The Wiltshire Times, 11 August 1928

[8] The Wiltshire Times, 28 November 1931 and 2 July 1938

[9] The Wiltshire Times, 25 December 1954 and 23 January 1954

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 18 October 1919

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 2 June 1923

[3] Courtesy Stella Clarke

[4] North Wilts Herald, 20 April 1928 and The Wiltshire Times, 10 August 1929

[5] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 1 September 1928

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 25 April 1931

[7] The Wiltshire Times, 11 August 1928

[8] The Wiltshire Times, 28 November 1931 and 2 July 1938

[9] The Wiltshire Times, 25 December 1954 and 23 January 1954