How Vulgar was Georgian Box? Alan Payne December 2018

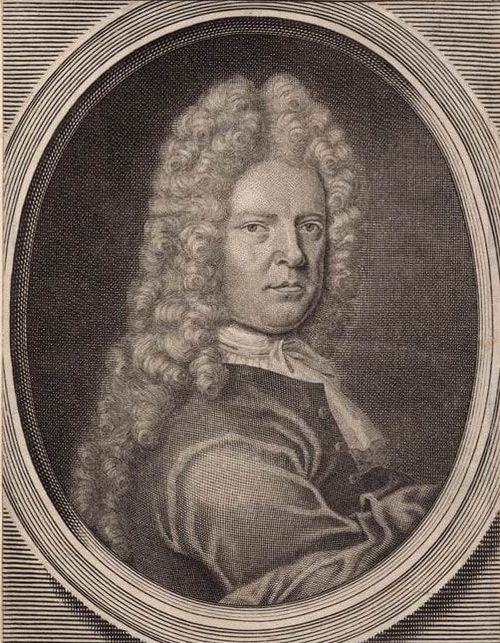

The connections in this article are convoluted but in essence they involve a conflict between the two men seen above: Ned Ward, a High-Church Tory and a renowned Georgian satirist, and Sir Edward Northey, Attorney-General of the crown and lord of the manor of Box. The battleground was Ned's accusation that Queen Anne failed to support the Tories in Parliament. But we need to put their actions into context first.

The Newspaper Age

There was a huge increase in the production of newspapers in the 1700s after the Press Licensing Act was allowed to lapse in 1695. The government tried to restrict propaganda through seditious libel prosecutions, the 1712 Stamp Act taxing newspapers and its own propagandists like Defoe and Swift. But freedom of the press became an essential part of English Liberties and private book publications, handbills and the provincial press pushed the boundaries of political and moral decency. And everywhere was an insatiable public interest in information as literacy levels grew. In 1738-39 male literacy in Wiltshire was given as 56% and female 44%.[1] Against this background came Ned Ward and Edward Northey, both of whom were connected with the story of Box.

Edward (Ned) Ward

Ned Ward wrote over a hundred books which were published nationally but are rarely read these days: too long, rather obtuse, full of Greek and Latin references that pass us by. But during the years of Queen Anne's rule in England between 1702 and 1714 they were explosive, the equivalent of Mock the Week, Spitting Image and That Was The Week That Was all rolled into one.

He published his works throughout Britain after the government relaxed censorship by not renewing various Press Licensing laws in 1695. The vehemence of Ward's writings can be seen from the following poems: on the left veiled description of the heirless Queen; and right immoral behaviour in general.

The Newspaper Age

There was a huge increase in the production of newspapers in the 1700s after the Press Licensing Act was allowed to lapse in 1695. The government tried to restrict propaganda through seditious libel prosecutions, the 1712 Stamp Act taxing newspapers and its own propagandists like Defoe and Swift. But freedom of the press became an essential part of English Liberties and private book publications, handbills and the provincial press pushed the boundaries of political and moral decency. And everywhere was an insatiable public interest in information as literacy levels grew. In 1738-39 male literacy in Wiltshire was given as 56% and female 44%.[1] Against this background came Ned Ward and Edward Northey, both of whom were connected with the story of Box.

Edward (Ned) Ward

Ned Ward wrote over a hundred books which were published nationally but are rarely read these days: too long, rather obtuse, full of Greek and Latin references that pass us by. But during the years of Queen Anne's rule in England between 1702 and 1714 they were explosive, the equivalent of Mock the Week, Spitting Image and That Was The Week That Was all rolled into one.

He published his works throughout Britain after the government relaxed censorship by not renewing various Press Licensing laws in 1695. The vehemence of Ward's writings can be seen from the following poems: on the left veiled description of the heirless Queen; and right immoral behaviour in general.

|

So the Fair Mistress of the Town,

When Young and Wholsome, will go down, But with the Crinkums (woman's sexual parts) once infected, She's by the meanest Rake rejected. Thus Surgeons, like to Lawyers, make The best of what they undertake; And tho' they cure our Ailings first, The After-clap proves always worst. So Dogs-turd, when it's dry'd, becomes A Med'cine rare for ulcer'd Gums, And of all Powders is the best For a Sore-Throat. Probatum est. (It has been proved) |

Another poem reads:

When entering the ladies by mistake And who should come running immediately after But a pretty young damsel to scatter her water, Who being in haste had the scurvy mishap To thrust open the door and clap arse on my lap As wound, said I, Lady Fair was unchristian And never deserving your sex to be pissed on. |

We know that Ned Ward travelled through the parish of Box because he recorded this in A Step to the Bath, 1700.[2] He was in a bad mood when he described his welcome in the city, greeted by Catgut Scrapers (violinists), irritated by the difficulties of his journey there. He recalled the appalling condition of the route at Sandy Lane with water so deep it took three hours to cover two miles. He described his route via Shepherd's Shore, Sandy Lane, Lacock and Corsham to Kingsdown as being: Rocky, Unlevel, and Narrow in some places, that Ned was sure the Alps could be passed with less danger. At last, when they had almost given up hope of a safe arrival, they reached Bath. But it was really the Queen that most of Ward's invective was aimed at.

Queen Anne, 1702 - 14

Anne, the daughter of the Catholic James II, broke with her father and was a prominent Protestant, much to the pleasure of the British Members of Parliament, who agreed her succession to the throne after the deaths of her sister Mary and her husband William of Orange. But in these years of troubled religious succession, Anne failed to produce an heir to ensure stability. Reputedly she was pregnant seventeen times in as many years but none of the children survived her. She suffered severe gout, became very obese, and could only move around carried in a sedan chair.

For contemporaries like the Duchess of Marlborough, she was weak, influenced by personalities rather than policies, ignorant and with very little judgement. Politically, her reign saw a sharpening of the Whig and Tory factions in parliament and her own stubborn character and intrigues in her household did little to establish a consensus of political opinion during the years of European conflict called the Wars of Spanish Succession. Against these difficulties, the queen herself suffered considerable public ridicule, until she could bear no more and instructed Sir Edward Northey, attorney-general, to sue Ward.

Trial of Ned Ward, April 1706

Ned's trial was held in the Court of the Queen's Bench. He was charged with being a seditious, malicious and ill-disposed man.

He had published scandalous and seditious libels ... he had assiduously and perpetually disturbed the peace and tranquillity of the realm. The passages that offended the court were not the obscene ones spiced with defamation, obscenities, sexual descriptions, cuckoldry and worse, in which he described London clubs including The Lying Club, The Beggars Club, Mollie Houses (gay clubs) and The Farting Club. Ward frequently recounted in detail pissing by men and women, sexual entry, defecating and the passing of wind. His obscenities were so extreme that still some of his books haven't been published.

Ward's offence was his criticism of Queen Anne and her realm (government). Nowadays his rebukes of the Queen seem mild but they were perceived as threatening stability and were so widely read that the government felt obliged to take a stand. They made him an example to show their intention to prosecute gratuitous defamation. An example of this criticism is:

No Wonder, since there's no such thing

As Honour, where there is no King;

For Honour, every Body knows,

From Crowns originally flows:

And where there's no Crown'd-Head to give it,

No Man can merit or receive it.

Ward was found guilty and ordered to be held in pillory, a comparatively minor punishment but degrading for the author.

Sir Edward Northey

Sir Edward Northey was a famous constitutional lawyer of the time and after fifteen years in private practice was appointed Attorney-General in 1701. His role was to prosecute many controversial political trials including that of Ned Ward, who was found guilty and sentenced to be held in the pillory (similar to stocks). Sir Edward was richly rewarded for his work and in 1701 given a knighthood.

Although his main estate was in Epsom, Sir Edward was the founder of the Northey dynasty in Box who were lords of the manor for over 200 years. It is possible that Sir Edward bought the Ashley estate in Box after 1710 when he became Member of Parliament for Tiverton, Devon. Having taken such a strong line in Ned Ward's case, we might imagine that the Northey family imposed a similar discipline on their tenants in Box. It obviously succeeded and 100 years later the tone of Box residents might be judged through the work of Thomas Bowdler.

Queen Anne, 1702 - 14

Anne, the daughter of the Catholic James II, broke with her father and was a prominent Protestant, much to the pleasure of the British Members of Parliament, who agreed her succession to the throne after the deaths of her sister Mary and her husband William of Orange. But in these years of troubled religious succession, Anne failed to produce an heir to ensure stability. Reputedly she was pregnant seventeen times in as many years but none of the children survived her. She suffered severe gout, became very obese, and could only move around carried in a sedan chair.

For contemporaries like the Duchess of Marlborough, she was weak, influenced by personalities rather than policies, ignorant and with very little judgement. Politically, her reign saw a sharpening of the Whig and Tory factions in parliament and her own stubborn character and intrigues in her household did little to establish a consensus of political opinion during the years of European conflict called the Wars of Spanish Succession. Against these difficulties, the queen herself suffered considerable public ridicule, until she could bear no more and instructed Sir Edward Northey, attorney-general, to sue Ward.

Trial of Ned Ward, April 1706

Ned's trial was held in the Court of the Queen's Bench. He was charged with being a seditious, malicious and ill-disposed man.

He had published scandalous and seditious libels ... he had assiduously and perpetually disturbed the peace and tranquillity of the realm. The passages that offended the court were not the obscene ones spiced with defamation, obscenities, sexual descriptions, cuckoldry and worse, in which he described London clubs including The Lying Club, The Beggars Club, Mollie Houses (gay clubs) and The Farting Club. Ward frequently recounted in detail pissing by men and women, sexual entry, defecating and the passing of wind. His obscenities were so extreme that still some of his books haven't been published.

Ward's offence was his criticism of Queen Anne and her realm (government). Nowadays his rebukes of the Queen seem mild but they were perceived as threatening stability and were so widely read that the government felt obliged to take a stand. They made him an example to show their intention to prosecute gratuitous defamation. An example of this criticism is:

No Wonder, since there's no such thing

As Honour, where there is no King;

For Honour, every Body knows,

From Crowns originally flows:

And where there's no Crown'd-Head to give it,

No Man can merit or receive it.

Ward was found guilty and ordered to be held in pillory, a comparatively minor punishment but degrading for the author.

Sir Edward Northey

Sir Edward Northey was a famous constitutional lawyer of the time and after fifteen years in private practice was appointed Attorney-General in 1701. His role was to prosecute many controversial political trials including that of Ned Ward, who was found guilty and sentenced to be held in the pillory (similar to stocks). Sir Edward was richly rewarded for his work and in 1701 given a knighthood.

Although his main estate was in Epsom, Sir Edward was the founder of the Northey dynasty in Box who were lords of the manor for over 200 years. It is possible that Sir Edward bought the Ashley estate in Box after 1710 when he became Member of Parliament for Tiverton, Devon. Having taken such a strong line in Ned Ward's case, we might imagine that the Northey family imposed a similar discipline on their tenants in Box. It obviously succeeded and 100 years later the tone of Box residents might be judged through the work of Thomas Bowdler.

|

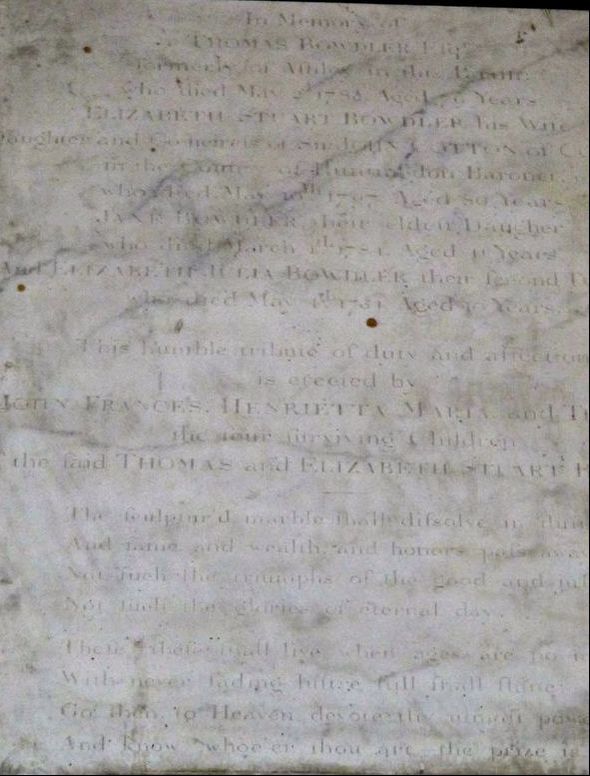

Family Shakespeare by Thomas Bowdler, 1807

Years before Mary Whitehouse's stand on morality, Dr Thomas Bowdler set about correcting Shakespeare to make it suitable for public consumption by omitting words and expressions which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family. In other words all the rude, and mostly humorous, bits.[3] The author's parents, Thomas and his wife Elizabeth Stuart Bowdler, lived at Ashley, at times with their son Dr Thomas Bowdler, who was born there in 1752 and died at Swansea in 1825. Dr Thomas' father was buried in the churchyard of St Thomas a Becket, Box, on 2 May 1785, as was his mother. We might imagine that Dr Thomas' childhood in Box influenced his views as Gladys Rogers of Box wrote in 1933, This family of Bowdler seems to have been of a gloomy turn of mind, finding very little in life but the sordid and unpleasant.[4] So, to answer the question how vulgar was Georgian Box? Not very after the Northey family came into the village in 1706 and emerging Victorian morality began to affect our thinking. Right: The Bowdler epitaph in Box Church (courtesy Carol Payne) |

References

[1] EJ Hobsbawm and George Rudé, Captain Swing, 1969, Penguin Books, p.42

[2] Ned Ward, A Step to the Bath, 1700 quoted in Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, p.78

[3] See http://www.bowdlers.com/page36.html

[4] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 7 October 1933

[1] EJ Hobsbawm and George Rudé, Captain Swing, 1969, Penguin Books, p.42

[2] Ned Ward, A Step to the Bath, 1700 quoted in Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, p.78

[3] See http://www.bowdlers.com/page36.html

[4] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 7 October 1933