Farming Depression in Late Victorian Box Alan Payne July 2015

Written with the generous help of Shirley and Ainslie Goulstone for pictures and details

Written with the generous help of Shirley and Ainslie Goulstone for pictures and details

Farming Depression, 1873 - 1920s

The late Victorian period was one of severe agricultural depression, particularly in arable production. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 abolished the import tax on corn leaving British farmers unprotected from imported agricultural produce. A reduction in international freight rates starting about 1873 further narrowed any cost advantage that Britain had in relation to American and Canadian cereals producers where large-scale prairie agriculture was considerably cheaper than home-produced methods.[1]

Arable farmers were the worst-affected but there were some difficulties for animal producers with cheap imported meat from Australia and New Zealand and reductions in imported fodder prices, especially high protein concentrates, which became a mainstay for over-wintering dairy cows and further reduced agriculture at home. Rents fell by 10% to 20% and the Smallholdings Act of 1892 empowered Councils to mitigate emigration and rural decline by buying land for renting out as farms under 50 acres on easy terms.

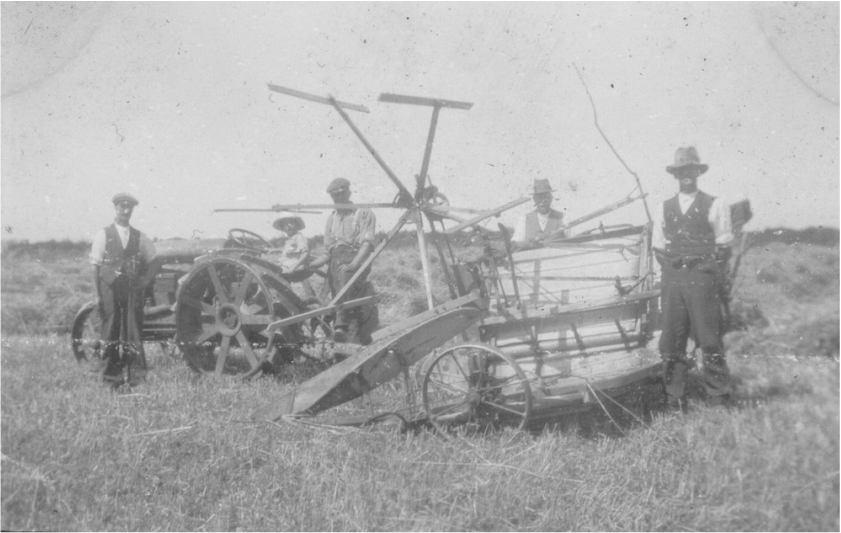

Manual labour was the mainstay of most farms at the start of this period, often characterised by a rank of cottages on the farm offering tied accommodation for agricultural workers on minimal rents. Farmers sought to reduce their labour costs and it was steam power which altered farming practices, partly replacing horse and human power. Steam engines were used to grind corn, slice root feed and break up cattle cake, which eased some farming routines but was far from the impact that the internal combustion engine had for later generations.[2] Compared to modern technological developments, it was all rather small beer.

The late Victorian period was one of severe agricultural depression, particularly in arable production. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 abolished the import tax on corn leaving British farmers unprotected from imported agricultural produce. A reduction in international freight rates starting about 1873 further narrowed any cost advantage that Britain had in relation to American and Canadian cereals producers where large-scale prairie agriculture was considerably cheaper than home-produced methods.[1]

Arable farmers were the worst-affected but there were some difficulties for animal producers with cheap imported meat from Australia and New Zealand and reductions in imported fodder prices, especially high protein concentrates, which became a mainstay for over-wintering dairy cows and further reduced agriculture at home. Rents fell by 10% to 20% and the Smallholdings Act of 1892 empowered Councils to mitigate emigration and rural decline by buying land for renting out as farms under 50 acres on easy terms.

Manual labour was the mainstay of most farms at the start of this period, often characterised by a rank of cottages on the farm offering tied accommodation for agricultural workers on minimal rents. Farmers sought to reduce their labour costs and it was steam power which altered farming practices, partly replacing horse and human power. Steam engines were used to grind corn, slice root feed and break up cattle cake, which eased some farming routines but was far from the impact that the internal combustion engine had for later generations.[2] Compared to modern technological developments, it was all rather small beer.

Dairy Farming

To try to make a profit, the North Wiltshire area turned from the traditional mixed arable and animal farming to pure dairy farming in the late Victorian period.[3] Dairy farming (or more precisely liquid milk production) was safe from overseas competition and could rely on the rail network for cheap distribution to urban centres.

It wasn't a smooth transition: the cattle plague of 1865 killed a quarter of a million animals and measures were needed to improve sanitary housing of animals.[4] The Royal Agricultural Society of England encouraged model cheese-making factories after 1870 to compete with imported cheese and North Wiltshire began to specialise in milk and cheese production.

To try to make a profit, the North Wiltshire area turned from the traditional mixed arable and animal farming to pure dairy farming in the late Victorian period.[3] Dairy farming (or more precisely liquid milk production) was safe from overseas competition and could rely on the rail network for cheap distribution to urban centres.

It wasn't a smooth transition: the cattle plague of 1865 killed a quarter of a million animals and measures were needed to improve sanitary housing of animals.[4] The Royal Agricultural Society of England encouraged model cheese-making factories after 1870 to compete with imported cheese and North Wiltshire began to specialise in milk and cheese production.

|

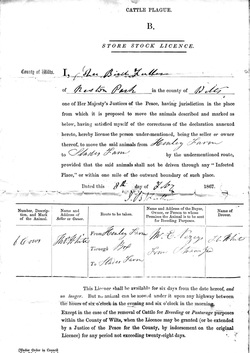

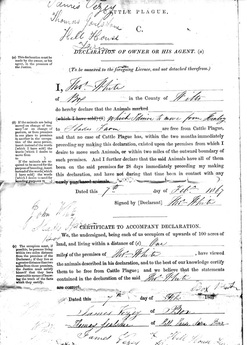

Cattle Plague Right: Licence dated 8 February 1867 to move 6 cows from Henley Farm to Slades Farm at the height of the Cattle Plague. The licence required the confirmation of James Vezey, butcher at the Chequers, and Thomas Goulstone and the authorisation of John Fuller of Neston Park as Wiltshire Justice of the Peace. Document courtesy Shirley Goulstone |

In 1884 the Prince of Wales advocated silage making for fodder to avoid problems with hay (such as adverse weather) and root crops (price problems) but the erection of silos was too expensive for many and it was in modern times that its full importance was realised.[5] Dairy Shorthorn cows were introduced which gave better milk yields and local farmers developed specific milking buildings.[6] Cattle sheds (skillings) with creosote walls and galvanised corrugated roofs offered better conditions where cows were tied up by rope or chain to posts, able to stand up or sit down, eating from mangers.[7] The number of cattle increased by 35% in North Wiltshire.[8]

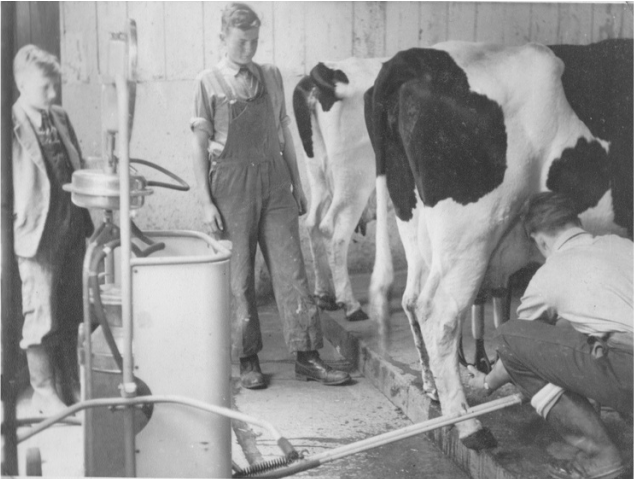

The use of the Hosier milking system (a Wiltshire invention) in the 1920's revolutionised dairy methods. The mobile milking parlour had stalls for six cows, a power plant for the milking machine and electric light. By taking the parlour to the animals, milking became a two-man job and enabled access in remote fields.[9] In 1926 a Milk and Dairies Order to local councils emphasised the need for sterile milking conditions: washing troughs, steam-cleaning, proper ventilation.[10]

Without hygienic conditions, outbreaks of foot and mouth disease were endemic in Wiltshire and Oxfordshire.[11] In 1924 Gloucestershire imposed a county standstill order to try to combat outbreaks. In 1925-26 the Goulstones lost their whole herd to the disease at Hill House Farm.[12]

The use of the Hosier milking system (a Wiltshire invention) in the 1920's revolutionised dairy methods. The mobile milking parlour had stalls for six cows, a power plant for the milking machine and electric light. By taking the parlour to the animals, milking became a two-man job and enabled access in remote fields.[9] In 1926 a Milk and Dairies Order to local councils emphasised the need for sterile milking conditions: washing troughs, steam-cleaning, proper ventilation.[10]

Without hygienic conditions, outbreaks of foot and mouth disease were endemic in Wiltshire and Oxfordshire.[11] In 1924 Gloucestershire imposed a county standstill order to try to combat outbreaks. In 1925-26 the Goulstones lost their whole herd to the disease at Hill House Farm.[12]

Milk, Cheese and Pigs

Using the rail network, farms were able to sell dairy produce to local factories and into London.[13] Milk depots were set up at Semley in 1871, Chippenham in 1873 and Stratton in 1879.[14] A famous North Wiltshire loaf cheese was developed and had great success with an annual turnover of 5,000 tons in competition with Gloucester cheese.[15] But Cheddar cheese-making squeezed out Wiltshire producers so that by 1914 the Wiltshire cheese industry had virtually ceased.[16]

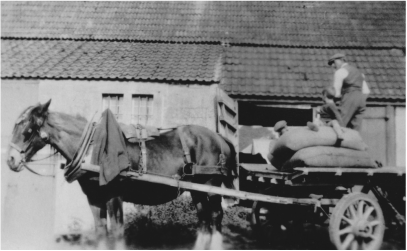

The whey from the milk was sold to pig breeders as feed. The bacon industry with Harris’ at Calne, and the Nestle factory at Chippenham are ancillary trades for milk surpluses and by-products. Pig farming (the end process in cheese making) grew by 50% between 1880 and 1930 but beef production suffered greatly from cheap imports. Instead farmers turned to poultry, mostly for eggs, with low labour involvement and low feed costs.

Using the rail network, farms were able to sell dairy produce to local factories and into London.[13] Milk depots were set up at Semley in 1871, Chippenham in 1873 and Stratton in 1879.[14] A famous North Wiltshire loaf cheese was developed and had great success with an annual turnover of 5,000 tons in competition with Gloucester cheese.[15] But Cheddar cheese-making squeezed out Wiltshire producers so that by 1914 the Wiltshire cheese industry had virtually ceased.[16]

The whey from the milk was sold to pig breeders as feed. The bacon industry with Harris’ at Calne, and the Nestle factory at Chippenham are ancillary trades for milk surpluses and by-products. Pig farming (the end process in cheese making) grew by 50% between 1880 and 1930 but beef production suffered greatly from cheap imports. Instead farmers turned to poultry, mostly for eggs, with low labour involvement and low feed costs.

Arable and Sheep

Arable farming was still essentially mixed arable and animal. The animals, whether sheep or cattle fattening, were needed to manure the soil and break it down. It was the same system which had existed for many centuries even from Saxon times. In Box it was sheep who were used to tread the ploughed soil mosty because they were easier to manoeuvre on the hilly corn lands.

Arable farming was still essentially mixed arable and animal. The animals, whether sheep or cattle fattening, were needed to manure the soil and break it down. It was the same system which had existed for many centuries even from Saxon times. In Box it was sheep who were used to tread the ploughed soil mosty because they were easier to manoeuvre on the hilly corn lands.

Traditional labour-intense methods were increasingly outdated. In 1900 the dung cart in the centre of the village was still a regular sight and many farmers continued to rely on mucking their fields from a central muck heap with pitchfork-spreading. The pitching of newly dried hay onto hay wagons, the compression of the hay into bales and its stacking into hayricks in the rickyard were annual rural events. At times Box School was closed for gleaning (picking ears of corn off the harvested land) and bees were rung home by making a loud noise with tins and sticks.[17]

Where improved techniques were introduced, they caused a down-sizing of the labour force, particularly unskilled workers. In some places machine-threshing replaced hand-threshing, which had previously employed a number of people during the winter months. The first combine harvesters were introduced into England in 1928, but it was only after the Second World War that they were in general use in Wiltshire. Farm labourers in the county reduced from 27,000 in 1871 to just 4,520 in 1971.[18] The number of sheep in Box valley also declined. From the 1920’s corn crops were increasingly dependent on artificial fertilisers, rather than the combination of corn and animals for natural manuring. And the medieval dependence of the wool industry on local sheep had long since ended.

Where improved techniques were introduced, they caused a down-sizing of the labour force, particularly unskilled workers. In some places machine-threshing replaced hand-threshing, which had previously employed a number of people during the winter months. The first combine harvesters were introduced into England in 1928, but it was only after the Second World War that they were in general use in Wiltshire. Farm labourers in the county reduced from 27,000 in 1871 to just 4,520 in 1971.[18] The number of sheep in Box valley also declined. From the 1920’s corn crops were increasingly dependent on artificial fertilisers, rather than the combination of corn and animals for natural manuring. And the medieval dependence of the wool industry on local sheep had long since ended.

Stooks made the old-fashioned way by John Best at Ingalls Farm (photos courtesy CMP)

Kingsdown Sheep Fair

An important annual event in the farming calendar was the sheep fair held at Kingsdown every 15 September. The event was hugely popular. In 1875 the Western Gazette carried a notice on 17 September reporting, Kingsdown Great Sheep and Horse Fair: The number of sheep was under 50,000, many thousands below the general average. The event was part agricutural show, part community festivities and part animal trading time. It was also the place to settle farming debts and to recruit labour.[19] Often they were occasions for enjoyment with sideshows and entertainment but sometimes the excitement and the alcohol ended in excess as when Michael Henchard in Hardy's The Mayor of Casterbridge sold his wife.

The fair area attracted sheep dealers from a wide area and was popular as an alternative to Castle Combe, which was the main regional sheep fair.[20] The sheep often came in by train and were driven up the hill. Various field references identify Kingsdown with sheep grazing. The field called Eucreds Haye was used as an enclosure for lambing or for dipping ewes.[21] Wever Hayes probably refers to sheep breeding (wether).

It was also a hiring fair where men, often led by a gang leader, offered themselves for employment for the coming season. Often young men and women offered their services for the forthcoming year as trade apprentices or as indoor or agricultural servants. The Fair continued for centuries and Neston school records how popular it was on 20 September 1876: Attendance slack due to Kingsdown Fair (sheep).[22]

The fair was held on the South Wraxall side of the present road and existed until the 1930s.[23] Little is left to remember the event now but for many years in the stone barn on the Golf Course the hurdles for the pens were stored on the beams of the building.[24]

An important annual event in the farming calendar was the sheep fair held at Kingsdown every 15 September. The event was hugely popular. In 1875 the Western Gazette carried a notice on 17 September reporting, Kingsdown Great Sheep and Horse Fair: The number of sheep was under 50,000, many thousands below the general average. The event was part agricutural show, part community festivities and part animal trading time. It was also the place to settle farming debts and to recruit labour.[19] Often they were occasions for enjoyment with sideshows and entertainment but sometimes the excitement and the alcohol ended in excess as when Michael Henchard in Hardy's The Mayor of Casterbridge sold his wife.

The fair area attracted sheep dealers from a wide area and was popular as an alternative to Castle Combe, which was the main regional sheep fair.[20] The sheep often came in by train and were driven up the hill. Various field references identify Kingsdown with sheep grazing. The field called Eucreds Haye was used as an enclosure for lambing or for dipping ewes.[21] Wever Hayes probably refers to sheep breeding (wether).

It was also a hiring fair where men, often led by a gang leader, offered themselves for employment for the coming season. Often young men and women offered their services for the forthcoming year as trade apprentices or as indoor or agricultural servants. The Fair continued for centuries and Neston school records how popular it was on 20 September 1876: Attendance slack due to Kingsdown Fair (sheep).[22]

The fair was held on the South Wraxall side of the present road and existed until the 1930s.[23] Little is left to remember the event now but for many years in the stone barn on the Golf Course the hurdles for the pens were stored on the beams of the building.[24]

Farming Occupations in 1911

We get a fascinating snap-shot of work in the village from the 1911 census. Employment in Box was still strongly based on traditional rural occupations as it had been for centuries. 22% of household heads in the village were farmers, farm labourers or in agricultural trades and they lived throughout the area. Unlike some areas, however, Box was not solely dependent on agriculture and 33% of heads were in the quarry trade.

Most farm workers were employed rather than self-employed, even trades suited to contract work. James Ford aged 70 who lived at Woodbine Cottage, Middlehill, was employed as a Cowman. William Horne at Holme Leigh, Valens Terrace, was employed as a Hay Cutter for a hay merchant. One of the few self employed persons in the dairy trade was Richard Weeks at Alpha House (now called Hardy House), a 70 year old dairyman. Joseph Laurence worked on his Own Account as a harness-maker and lived in six rooms at 1 Belle Vue.

There were also specialist rural occupations. Frederick Hancock (aged 23) at Washwells was a farm Horseman, Samuel Cowley (25) boarder at Fair Mead View called himself Saddler. In some areas sheep were run for their own sake: Edward Wilkins was a 50 year old shepherd living at Rudloe Cottages with a boarder Charles Fowler, cowman; Thomas Dowdell (62) at Lower Rudloe Cottages was a gamekeeper; William Say (44) at The Laurels, Middlehill, was an Agent for Cattle Cake. Henry Clarke (28) who lived on the High Street was a blacksmith. Robert Hall at 5 Prospect Cottages was a Vegetable Grower for Market.

We get a fascinating snap-shot of work in the village from the 1911 census. Employment in Box was still strongly based on traditional rural occupations as it had been for centuries. 22% of household heads in the village were farmers, farm labourers or in agricultural trades and they lived throughout the area. Unlike some areas, however, Box was not solely dependent on agriculture and 33% of heads were in the quarry trade.

Most farm workers were employed rather than self-employed, even trades suited to contract work. James Ford aged 70 who lived at Woodbine Cottage, Middlehill, was employed as a Cowman. William Horne at Holme Leigh, Valens Terrace, was employed as a Hay Cutter for a hay merchant. One of the few self employed persons in the dairy trade was Richard Weeks at Alpha House (now called Hardy House), a 70 year old dairyman. Joseph Laurence worked on his Own Account as a harness-maker and lived in six rooms at 1 Belle Vue.

There were also specialist rural occupations. Frederick Hancock (aged 23) at Washwells was a farm Horseman, Samuel Cowley (25) boarder at Fair Mead View called himself Saddler. In some areas sheep were run for their own sake: Edward Wilkins was a 50 year old shepherd living at Rudloe Cottages with a boarder Charles Fowler, cowman; Thomas Dowdell (62) at Lower Rudloe Cottages was a gamekeeper; William Say (44) at The Laurels, Middlehill, was an Agent for Cattle Cake. Henry Clarke (28) who lived on the High Street was a blacksmith. Robert Hall at 5 Prospect Cottages was a Vegetable Grower for Market.

Landlords

We get a fascinating insight into the terms of agricultural tenancies with the lease dated March 1920 between GE Northey, Esq, landlord, and Philip James Goulstone, tenant for Hill House Farm.[25] The tenancy was for 14 years at a fixed rent of £310 per annum. The landlord and his agent clearly anticipated no great inflation in rent prices.

Of interest is that the landlord made reservations on the types of crops that could be grown with restrictions on planting no more than two white straw crops in succession, insisting on a four-course system of husbandry. There were general clauses such as to keep the farm free and clear from weeds and in good heart and condition, prudent clauses that the tenant should insure his straw and feedstuffs, and clauses to safeguard the value of the timber rights (which were exempted to the landlord) not to put a nail into any tree sappling or pollard.

We get a perspective on the deference shown to the lord of the manor in a newspaper article about the silver wedding celebrations of George Northey, Esq in 1910: in a quiet but happy manner. It was a red letter day for the tenantry of Box and Ashley, with which Mr and Mrs Northey are so closely identified. Mr Northey is exceedingly popular and the gathering at Cheney Court showed the high esteem and regard in which both Mr and Mrs Northey are held.[26]The smallholder farmers and the cottagers joined together to give silver flower vases and candelabra to which Mr Northey said, He had not had much opportunity of doing very much for them up to the present time but if anything needed to be done he would be very pleased to do all that he possibly could.

At a dinner for the farming tenants held in the garage of Cheney Court, the tenant farmers included E Hobbs (Cheney Court), F Goulstone (Hill House), George Pritchard (Ashley Farm), W Matthews (Sheylors), H Ford (Prospect), EA Snook (Blue Vein), H Rawlins (Old Jockey), R Hall (Prospect Gardens), Thomas Daniell (Old Manor Farm), J Blake (Hazelbury), F Rowe (Bayliff's Farm), W Long (Grove Farm), R Vezey (Vale View), G Martin (Spencer's Farm) and Davies (Ailsa Craig).[26]

We get a fascinating insight into the terms of agricultural tenancies with the lease dated March 1920 between GE Northey, Esq, landlord, and Philip James Goulstone, tenant for Hill House Farm.[25] The tenancy was for 14 years at a fixed rent of £310 per annum. The landlord and his agent clearly anticipated no great inflation in rent prices.

Of interest is that the landlord made reservations on the types of crops that could be grown with restrictions on planting no more than two white straw crops in succession, insisting on a four-course system of husbandry. There were general clauses such as to keep the farm free and clear from weeds and in good heart and condition, prudent clauses that the tenant should insure his straw and feedstuffs, and clauses to safeguard the value of the timber rights (which were exempted to the landlord) not to put a nail into any tree sappling or pollard.

We get a perspective on the deference shown to the lord of the manor in a newspaper article about the silver wedding celebrations of George Northey, Esq in 1910: in a quiet but happy manner. It was a red letter day for the tenantry of Box and Ashley, with which Mr and Mrs Northey are so closely identified. Mr Northey is exceedingly popular and the gathering at Cheney Court showed the high esteem and regard in which both Mr and Mrs Northey are held.[26]The smallholder farmers and the cottagers joined together to give silver flower vases and candelabra to which Mr Northey said, He had not had much opportunity of doing very much for them up to the present time but if anything needed to be done he would be very pleased to do all that he possibly could.

At a dinner for the farming tenants held in the garage of Cheney Court, the tenant farmers included E Hobbs (Cheney Court), F Goulstone (Hill House), George Pritchard (Ashley Farm), W Matthews (Sheylors), H Ford (Prospect), EA Snook (Blue Vein), H Rawlins (Old Jockey), R Hall (Prospect Gardens), Thomas Daniell (Old Manor Farm), J Blake (Hazelbury), F Rowe (Bayliff's Farm), W Long (Grove Farm), R Vezey (Vale View), G Martin (Spencer's Farm) and Davies (Ailsa Craig).[26]

Gathering of landlord and cottage tenants: Planting an oak tree at Ditteridge (where War Memorial was later built) to commemorate the silver wedding of George E Northey, Esq and his wife, Mabel, in 1910. The Northeys had built the unusual house behind, re-assembled from New Zealand (courtesy Shirley Goulstone).

Farmers

Most farmers employed live-in workers at home and were able to afford a single servant girl to manage the mud and dirt that they walked into the house. Edith Hancock aged 16 was a General Servant Domestic at Hatt Farm. At Wormwood Farm Richard Cook aged 49, lived with his wife and four children in ten rooms looked after by servant Kate Sevete, aged 20. George Pritchard, aged 55, lived in twelve rooms at Ashley Farm with his new wife Mabel, aged 33, and a niece Florence Kidner, aged 18. Richard Gent at Slades Farm lived in eight rooms with his wife, four children and 15 year old general domestic servant, Grace Humphries.

One of the farmers in central Box was Thomas Daniell (52), tenant at Manor Farm, who lived with his wife, seven children, a female visitor, and servant John Bottomley, Waggoner on Farm.

Most farmers employed live-in workers at home and were able to afford a single servant girl to manage the mud and dirt that they walked into the house. Edith Hancock aged 16 was a General Servant Domestic at Hatt Farm. At Wormwood Farm Richard Cook aged 49, lived with his wife and four children in ten rooms looked after by servant Kate Sevete, aged 20. George Pritchard, aged 55, lived in twelve rooms at Ashley Farm with his new wife Mabel, aged 33, and a niece Florence Kidner, aged 18. Richard Gent at Slades Farm lived in eight rooms with his wife, four children and 15 year old general domestic servant, Grace Humphries.

One of the farmers in central Box was Thomas Daniell (52), tenant at Manor Farm, who lived with his wife, seven children, a female visitor, and servant John Bottomley, Waggoner on Farm.

Structural Decline

Farming in the first half of the 1900s was in severe decline. At first it seemed to be just the usual agricultural poor weather years. The decline had started in the bad harvests of 1875-78 and the worst harvest of the century in 1879.[27] Farmers became subject to income tax after 1910, and in the 1920s and 1930s much land was left fallow or as rough grazing for livestock. The reduction in agricultural employment was dramatic: in 1900, 90% of Wiltshire’s working population was engaged in agriculture and allied trades; in 2000 the number is less than 2%.[28]

The decline appeared to be irreversible and nothing seemed to provide a long-term solution. At Pockeridge Quarry an underground mushroom farm was run by a French firm Agaric Mushroom Company Ltd under their foreman Mr Whittle who worked for them until the age of 84. By 1923 there were 5 hectares in cultivation producing up to 136,000 kilos of mushrooms a year.[29] The firm leased part of Tunnel Quarry for underground mushroom production but this ended in 1928 when the area became infected with a fungal disease.[30] The trade ceased in 1939 because of the war effort and was transferred to Bradford-on-Avon, never to return.

The guaranteed minimum agricultural wage of 46s.6d per week was stopped in 1921. The corn harvest was poor in 1921, and by June unemployment nationally reached 2 million. It was a period of great uncertainty. By 1923 there were nearly 3 million people unemployed nationally, almost a quarter of the insured working population.[31] And there were no answers on how to get back to stability.

In 1923 Vicar Sweetapple wrote about the situation: May God stir Box to cast off lethargy and carelessness and awake our higher interests. In Box the old order seemed to be breaking up, emphasised in December 1923 by the death of organist Augustus Frederick Perren, for 54 years the devoted servant of the Church in this Parish.[32]

Farming in the first half of the 1900s was in severe decline. At first it seemed to be just the usual agricultural poor weather years. The decline had started in the bad harvests of 1875-78 and the worst harvest of the century in 1879.[27] Farmers became subject to income tax after 1910, and in the 1920s and 1930s much land was left fallow or as rough grazing for livestock. The reduction in agricultural employment was dramatic: in 1900, 90% of Wiltshire’s working population was engaged in agriculture and allied trades; in 2000 the number is less than 2%.[28]

The decline appeared to be irreversible and nothing seemed to provide a long-term solution. At Pockeridge Quarry an underground mushroom farm was run by a French firm Agaric Mushroom Company Ltd under their foreman Mr Whittle who worked for them until the age of 84. By 1923 there were 5 hectares in cultivation producing up to 136,000 kilos of mushrooms a year.[29] The firm leased part of Tunnel Quarry for underground mushroom production but this ended in 1928 when the area became infected with a fungal disease.[30] The trade ceased in 1939 because of the war effort and was transferred to Bradford-on-Avon, never to return.

The guaranteed minimum agricultural wage of 46s.6d per week was stopped in 1921. The corn harvest was poor in 1921, and by June unemployment nationally reached 2 million. It was a period of great uncertainty. By 1923 there were nearly 3 million people unemployed nationally, almost a quarter of the insured working population.[31] And there were no answers on how to get back to stability.

In 1923 Vicar Sweetapple wrote about the situation: May God stir Box to cast off lethargy and carelessness and awake our higher interests. In Box the old order seemed to be breaking up, emphasised in December 1923 by the death of organist Augustus Frederick Perren, for 54 years the devoted servant of the Church in this Parish.[32]

The Victorian period wasn't the beginning of the end of farming in Box but it was another step in a long drawn out national process which has culminated with little farming left as a source of employment in the village today.

References

[1] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, p.165

[2] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, p.135

[3] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.78

[4] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, 1970, David & Charles, p.134

[5] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, p.184-7

[6] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.101

[7] Pamela M. Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, 1989, Wiltshire Buildings Record, p.66-7

[8] Bruce Watkin, A History of Wiltshire, 1989, Phillimore & Co

[9] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.111

[10] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, 1970, David & Charles, p.178

[11] The Gloucester Journal, 20 September 1924

[12] Parish Magazine, January 1926

[13] Pamela M. Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, p.9

[14] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.224

[15] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.78-9

[16] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.100-1

[17] Alfred Williams, In A Wiltshire Village, 1981, Alan Sutton, p.127, 136

[18] MC Corfield, Guide to Industrial Archaeology of Wiltshire, 1978, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.56

[19] Katherine Harris, notes in Wiltshire History Centre, p.3

[20] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 57

[21] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.119

[22] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, 1989, published by John Poulsom, p.75

[23] Katherine Harris, Up the Hill and Down the Hill

[24] Detail recalled by Mike Pope

[25] Courtesy Shirley Goulstone

[26] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[27] Jeremy Lake, Historic Farm Buildings, p.133

[28] Pamela M. Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, 1989, Wiltshire Buildings Record, p.3

[29] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.250

[30] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.17

[31] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066 - 1945, 1994, Harper Collins, p.696

[32] Parish Magazine, December 1923

[1] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, p.165

[2] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, p.135

[3] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.78

[4] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, 1970, David & Charles, p.134

[5] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, p.184-7

[6] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.101

[7] Pamela M. Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, 1989, Wiltshire Buildings Record, p.66-7

[8] Bruce Watkin, A History of Wiltshire, 1989, Phillimore & Co

[9] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.111

[10] Nigel Harvey, A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales, 1970, David & Charles, p.178

[11] The Gloucester Journal, 20 September 1924

[12] Parish Magazine, January 1926

[13] Pamela M. Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, p.9

[14] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.224

[15] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.78-9

[16] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.100-1

[17] Alfred Williams, In A Wiltshire Village, 1981, Alan Sutton, p.127, 136

[18] MC Corfield, Guide to Industrial Archaeology of Wiltshire, 1978, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, p.56

[19] Katherine Harris, notes in Wiltshire History Centre, p.3

[20] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 57

[21] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.119

[22] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, 1989, published by John Poulsom, p.75

[23] Katherine Harris, Up the Hill and Down the Hill

[24] Detail recalled by Mike Pope

[25] Courtesy Shirley Goulstone

[26] The Bath Chronicle, 16 June 1910

[27] Jeremy Lake, Historic Farm Buildings, p.133

[28] Pamela M. Slocombe, Wiltshire Farm Buildings 1500-1900, 1989, Wiltshire Buildings Record, p.3

[29] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.250

[30] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.17

[31] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066 - 1945, 1994, Harper Collins, p.696

[32] Parish Magazine, December 1923