|

William Smith, William Northey

and an unpaid bill Jonathan Parkhouse March 2019 On September 24th 1810 the surveyor and engineer William Smith drafted a letter to William Northey, the lord of the manor of Box,[1] asking for payment for work which he had undertaken for Northey some time previously. William Northey (1752-1826) Wicked Billy was Member of Parliament for Newport and a political maverick. His guests at Hazelbury included the Prince Regent and the gatherings there were reputedly noted for their debauchery; that he had not paid his account need not necessarily surprise us. Smith, on the other hand, was one of the most remarkable men of his age and is often described as the Father of English Geology.[2] His map of the geology of the country five miles around Bath of 1799 is the first geological map ever created and reaches to the edge of Box parish.[3] Right: William Smith (1769-1839) by Hugues Fourau (courtesy Wikipedia) |

He was the consummate multi-tasker, with a career as surveyor (of estates, canals and mines), engineer (with particular expertise in drainage, irrigation, sea defences and land-slip), author, geological and mineralogical consultant, and quarry owner/manager.[4]

He was also one of the unluckiest of men. After his dismissal from the Somerset Coal Canal Company in 1799, where he had been paid a respectable salary, he had to live on his skill and experience. He set up in business as a surveyor with Jeremiah Cruse at Trim Street in Bath, where he would be able to attract clients from the gentry who often stayed there. Despite this shrewd move, several of his clients went bankrupt before paying their bills, some took years to settle their accounts, whilst others, such as Northey, simply didn’t pay. His marriage, about which little is known, was evidently unhappy. His books failed to sell at anything approaching his expectations, his publisher went bankrupt twice and his bookseller once, whilst his literary assistant was imprisoned for libel. Smith was shunned by members of the Geological Society when it was founded in 1807 who seem to have thought themselves socially superior to Smith, and he had difficulties paying the mortgage on his property at Tucking Mill near Bath and the rent for his house in London. Almost all of his geological research he had to fund himself, and he travelled extensively between a number of clients in an age before the comforts afforded by railways or decent roads. Smith was imprisoned for debt in 1819,[5] but must have had financial difficulties for a considerable time before this. These pressures explain the tone of the letter Smith drafted to Northey in 1810:

To Willm Northey Esqr M.P.

Sir

When I had first the honour of being introduced to you at [ ] by Mr Crook [6] & you sent for Mr Large (then your tenant) to point out the land you wished to have drained I could not have had any apprehension of remaining so long without any recompense for my trouble.

It is not only for my own time and skill in that Business which remains unrewarded but I have never been reimbursed one farthing of the money which I paid to the Workmen. This ammounted [sic] to L S D and conceiving that the Farmer was to pay them I charged only L S D for my own skill in surveying the Ground, attending to the execution and paying the Workmen. Whether it was from a want of honesty in the Tenant or from knowing he was speedily to quit the Farm that I would get no money from him though repeatedly applied to I know not – neither can I be supposed to know how the terms of this Improvement were settled between him & you but it was only on acct of my coming at the request of Mr Crook to meet you at Box that the Business was undertaken and as you so shortly afterwards reaped the benefits of the Business both as owner and occupier of the Land I hope my appeal to you for some remuneration will not be considered as unjust or unfounded.

The improvement of the Field by the Draining and the consequent levelling of the open ditches with which it was disfigured is very conspicuous from the Turnpike and which I pass along so often and as I never look at Lands in any Country without an earnest desire to promote Improvements the springing places in the two Fields on each side & the improved appearance of the intermediate one will always bring to my recollection the sum I burried [sic] there – you Sir I know are too much of a Gentleman and too fond of Agricultural Improvements to let it be said or even thought that that Field owes so much of its better Herbage and improved appearance neither to the owner or Occupier but to one who has no interest whatsoever in the Soil.[7]

The work had evidently been undertaken some time before Smith wrote the letter. In January 1808 Smith had compiled a list of clients who had employed him since his dismissal by the Somerset Coal Canal Company in 1799, distinguishing between his clients on the basis of four categories of project: landslips, drainage, irrigation and embanking.[8] Northey is listed amongst those for whom Smith had undertaken drainage work. Several clients (although not Northey) were included on both the drainage list and the irrigation list, demonstrating the frequently close relationship between drainage (removal of water) and irrigation (supply of water, including the creation of watermeadows).

Smith kept a diary, and the volumes for the years between 1802 (shortly after Smith is likely to have first met Northey) and 1807 (by which time Smith must have worked for him) are preserved.[9] Frustratingly the diaries contain no reference to either Northey or Box during those years, although the level of detail recorded by Smith is variable, so the absence of any reference may simply mean that it was a relatively small-scale affair, and moreover one carried out within a short distance from Smith’s home in Bath and thus not requiring arduous travel. Smith had omitted to enter the financial details in the draft letter (presumably he needed to refer to a separate account book for the detail) so one cannot gauge the scale of work from the cost, but presumably the sum involved was felt to be worth trying to recover.

From the available evidence we may therefore reasonably suppose

Beyond this there are few clues as to the location of Smith’s work, but it is worth examining the statement that it was very conspicuous from the turnpike. The turnpike to which he refers would have been the route from Chippenham to Bath via Corsham and the edge of Hartham Park, as shown on Andrews and Dury’s 1773 map,[10] established by an Act of 1756-57;[11] the route was no doubt created in response to the increase in traffic from London to the developing resort of Bath and a desire to avoid the difficult steep section of the older route via Kingsdown. The route is essentially that followed by the present A4, but there have been some changes since Smith’s day. Minor re-alignment of the road took place close to Box village on construction of the railway tunnel in 1838-41, and the road through the village east of the junction with what is now Devizes Road was raised significantly as part of the same improvement. Smith’s view of the valley would not have been impeded by the railway, or by any roadside buildings beyond Manor House, although the section of road immediately beyond Manor House would have been closer to the floor of the side valley, restricting the sightlines. From the elevated position afforded by a horse or a coach parts of the valley floor northeast of the village would probably have been visible from the road, but only fleetingly and intermittently.[12]

On the balance of probability, then, Smith’s improvements are more likely to have been situated west of Box village. Aerial laser scanning data (also known as lidar)[13] released by the Environment Agency in 2015 shows a number of linear features along the By Brook valley floor which appear to be ditches associated with drainage or, possibly, water meadows. Most of these are northeast of Box village, and since they were largely invisible from the turnpike at the start of the nineteenth century are much less likely to have been the subject of Smith’s correspondence. Whilst there is no convincing reason to associate any particular feature as being related to the work undertaken by Smith, one area is of potential interest. This lies between Middlehill railway tunnel and the By Brook, in a field which in the early seventeenth century had been known as Ash Meade, and in the field immediately downstream on the opposite side of the By Brook. This area would have been clearly visible from the turnpike.

He was also one of the unluckiest of men. After his dismissal from the Somerset Coal Canal Company in 1799, where he had been paid a respectable salary, he had to live on his skill and experience. He set up in business as a surveyor with Jeremiah Cruse at Trim Street in Bath, where he would be able to attract clients from the gentry who often stayed there. Despite this shrewd move, several of his clients went bankrupt before paying their bills, some took years to settle their accounts, whilst others, such as Northey, simply didn’t pay. His marriage, about which little is known, was evidently unhappy. His books failed to sell at anything approaching his expectations, his publisher went bankrupt twice and his bookseller once, whilst his literary assistant was imprisoned for libel. Smith was shunned by members of the Geological Society when it was founded in 1807 who seem to have thought themselves socially superior to Smith, and he had difficulties paying the mortgage on his property at Tucking Mill near Bath and the rent for his house in London. Almost all of his geological research he had to fund himself, and he travelled extensively between a number of clients in an age before the comforts afforded by railways or decent roads. Smith was imprisoned for debt in 1819,[5] but must have had financial difficulties for a considerable time before this. These pressures explain the tone of the letter Smith drafted to Northey in 1810:

To Willm Northey Esqr M.P.

Sir

When I had first the honour of being introduced to you at [ ] by Mr Crook [6] & you sent for Mr Large (then your tenant) to point out the land you wished to have drained I could not have had any apprehension of remaining so long without any recompense for my trouble.

It is not only for my own time and skill in that Business which remains unrewarded but I have never been reimbursed one farthing of the money which I paid to the Workmen. This ammounted [sic] to L S D and conceiving that the Farmer was to pay them I charged only L S D for my own skill in surveying the Ground, attending to the execution and paying the Workmen. Whether it was from a want of honesty in the Tenant or from knowing he was speedily to quit the Farm that I would get no money from him though repeatedly applied to I know not – neither can I be supposed to know how the terms of this Improvement were settled between him & you but it was only on acct of my coming at the request of Mr Crook to meet you at Box that the Business was undertaken and as you so shortly afterwards reaped the benefits of the Business both as owner and occupier of the Land I hope my appeal to you for some remuneration will not be considered as unjust or unfounded.

The improvement of the Field by the Draining and the consequent levelling of the open ditches with which it was disfigured is very conspicuous from the Turnpike and which I pass along so often and as I never look at Lands in any Country without an earnest desire to promote Improvements the springing places in the two Fields on each side & the improved appearance of the intermediate one will always bring to my recollection the sum I burried [sic] there – you Sir I know are too much of a Gentleman and too fond of Agricultural Improvements to let it be said or even thought that that Field owes so much of its better Herbage and improved appearance neither to the owner or Occupier but to one who has no interest whatsoever in the Soil.[7]

The work had evidently been undertaken some time before Smith wrote the letter. In January 1808 Smith had compiled a list of clients who had employed him since his dismissal by the Somerset Coal Canal Company in 1799, distinguishing between his clients on the basis of four categories of project: landslips, drainage, irrigation and embanking.[8] Northey is listed amongst those for whom Smith had undertaken drainage work. Several clients (although not Northey) were included on both the drainage list and the irrigation list, demonstrating the frequently close relationship between drainage (removal of water) and irrigation (supply of water, including the creation of watermeadows).

Smith kept a diary, and the volumes for the years between 1802 (shortly after Smith is likely to have first met Northey) and 1807 (by which time Smith must have worked for him) are preserved.[9] Frustratingly the diaries contain no reference to either Northey or Box during those years, although the level of detail recorded by Smith is variable, so the absence of any reference may simply mean that it was a relatively small-scale affair, and moreover one carried out within a short distance from Smith’s home in Bath and thus not requiring arduous travel. Smith had omitted to enter the financial details in the draft letter (presumably he needed to refer to a separate account book for the detail) so one cannot gauge the scale of work from the cost, but presumably the sum involved was felt to be worth trying to recover.

From the available evidence we may therefore reasonably suppose

- that the work was carried out between Smith’s introduction to Northey, probably in 1800, and the compilation of his list of clients in January 1808

- that either it was undertaken during the years 1800-01, for which no journal survives, or it was of a scale small enough to escape mention in Smith’s diaries, but large enough to be worth pursuing the client for payment some years later

- that it involved primarily drainage rather than irrigation (which would include the creation of watermeadows) and is almost certainly to have been in the By Brook valley

- that the work was visible from the turnpike

- that the work involved the filling-in of ditches

- that there were springs (‘springing places’) in the fields either side of the works

- that the completed work represented an improvement on whatever had been there previously.

Beyond this there are few clues as to the location of Smith’s work, but it is worth examining the statement that it was very conspicuous from the turnpike. The turnpike to which he refers would have been the route from Chippenham to Bath via Corsham and the edge of Hartham Park, as shown on Andrews and Dury’s 1773 map,[10] established by an Act of 1756-57;[11] the route was no doubt created in response to the increase in traffic from London to the developing resort of Bath and a desire to avoid the difficult steep section of the older route via Kingsdown. The route is essentially that followed by the present A4, but there have been some changes since Smith’s day. Minor re-alignment of the road took place close to Box village on construction of the railway tunnel in 1838-41, and the road through the village east of the junction with what is now Devizes Road was raised significantly as part of the same improvement. Smith’s view of the valley would not have been impeded by the railway, or by any roadside buildings beyond Manor House, although the section of road immediately beyond Manor House would have been closer to the floor of the side valley, restricting the sightlines. From the elevated position afforded by a horse or a coach parts of the valley floor northeast of the village would probably have been visible from the road, but only fleetingly and intermittently.[12]

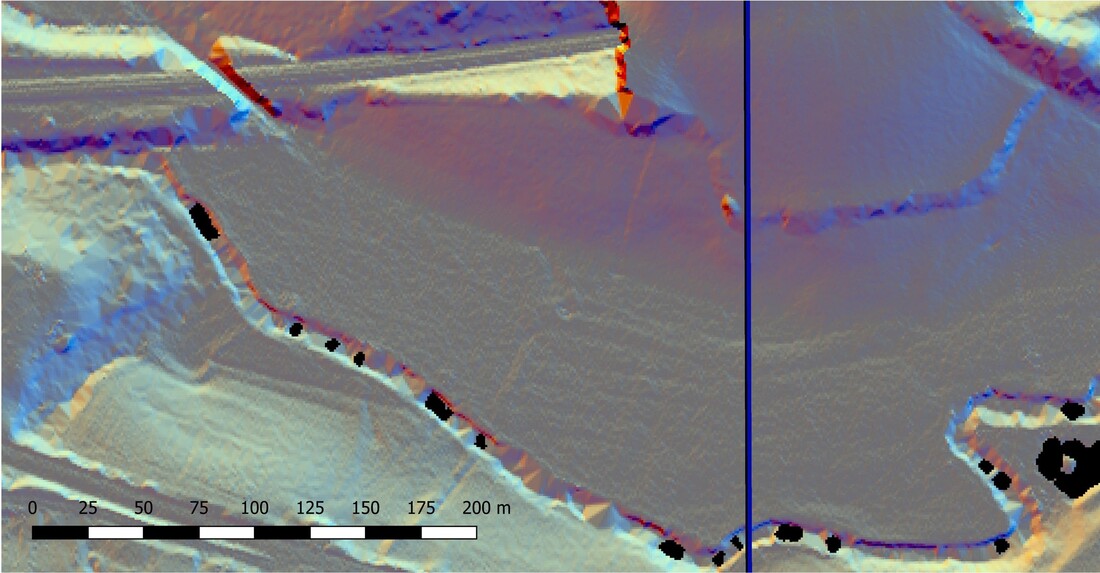

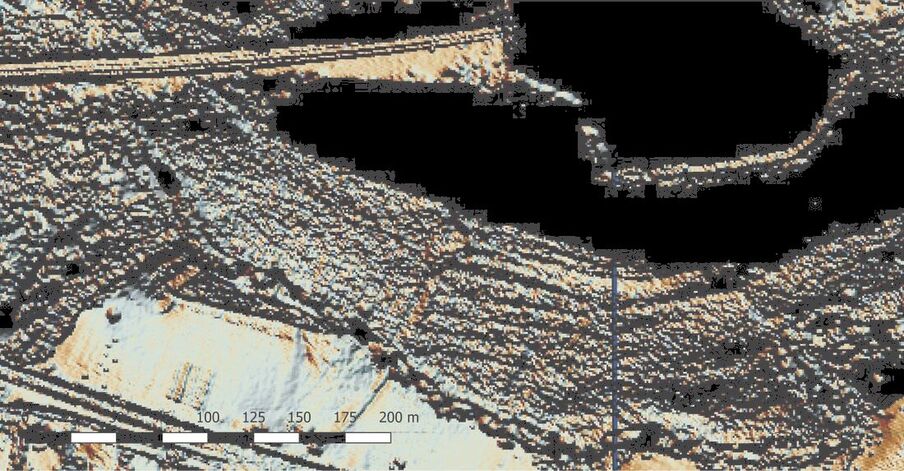

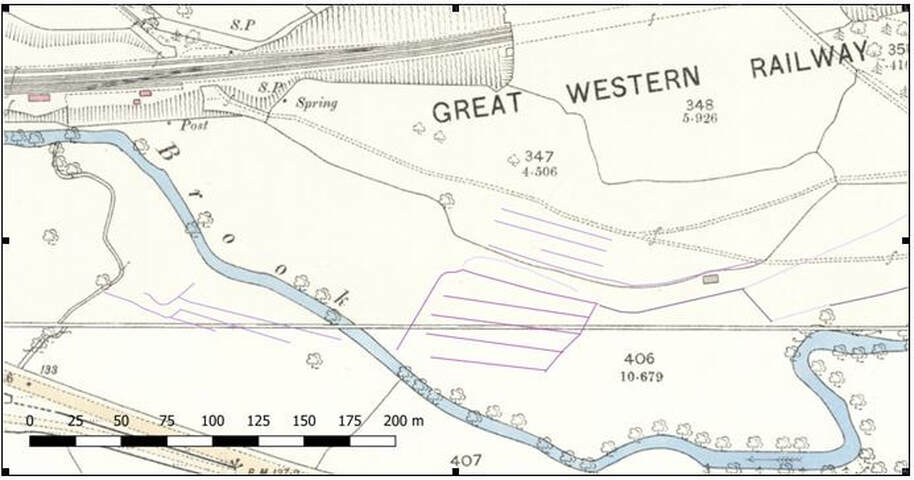

On the balance of probability, then, Smith’s improvements are more likely to have been situated west of Box village. Aerial laser scanning data (also known as lidar)[13] released by the Environment Agency in 2015 shows a number of linear features along the By Brook valley floor which appear to be ditches associated with drainage or, possibly, water meadows. Most of these are northeast of Box village, and since they were largely invisible from the turnpike at the start of the nineteenth century are much less likely to have been the subject of Smith’s correspondence. Whilst there is no convincing reason to associate any particular feature as being related to the work undertaken by Smith, one area is of potential interest. This lies between Middlehill railway tunnel and the By Brook, in a field which in the early seventeenth century had been known as Ash Meade, and in the field immediately downstream on the opposite side of the By Brook. This area would have been clearly visible from the turnpike.

Features revealed by lidar, southwest of Middlehill Tunnel. Top: Digital Terrain Model (DTM), 1m resolution (2005); multi-hill-shading combined with slope-gradient model. Centre: Digital Surface Model (DSM); analytical hill-shading (360o azimuth, sun elevation 25o) amalgamated with multidirectional hill-shading. Although the DSM image is ‘noisier’, the features north of the By Brook in Ash Meade are more distinct than on the DTM image. Bottom: tentative interpretative analysis (purple) overlying 1st edition 25” OS map (1886). Note the spring just south of the railway. Vertical line on upper figures and horizontal line across bottom figure are non-archaeological artifacts created by data tiling. Contains Environment Agency Information: © Environment Agency and database right 2018. Historic mapping reproduced with permission of the National Library of Scotland under terms of Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Sharealike licence (maps.nls.uk/index.html )

Here the lidar shows a number of linear features which are otherwise invisible. Those in Ash Meade consist of a series of short parallel ditches; these are superficially similar to the bedworks associated with water meadows, but much less extensive than is usual for such systems. It is difficult to see how such a small group of ditches could have actually functioned as a watermeadow since the highest section of ditch is actually above the level of the By Brook. Smith refers to springs in the field either side of the area where he had worked for Northey. A spring is shown on the 1st edition 25” OS map of 1886 in the field to the west, but no stream issues from it, and the construction of the railway and Middlehill tunnel, which at this point is close to the level of the spring lines, may very well have obliterated other springs and affected the local hydrology. Are the ditches remnants of an attempt to create a water meadow that was abandoned for some reason and which Smith was called in to sort out? Or is it more likely that these features were inserted in order to drain a low-lying area of land? Or did the work for Northey take place somewhere else, perhaps in the area around the Northey Arms and the former station and stone yard, where any traces of Smith’s endeavours will have been obliterated by subsequent activity? The hypothesis advanced here must be regarded as tentative at best, and the author would welcome any alternative explanations of the Ash Meade features. In the absence of further evidence, we can but speculate, and wonder whether Northey ever paid his debt.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Professor Emeritus Hugh Torrens, the leading authority on William Smith, and Kathleen Diston, Head of Print and Digital Collections at Oxford University Museum of Natural History, for assisting with information and access to material. The transcription of Smith’s letter to William Northey, however, and any errors in deciphering Smith’s handwriting, are my own.

Here the lidar shows a number of linear features which are otherwise invisible. Those in Ash Meade consist of a series of short parallel ditches; these are superficially similar to the bedworks associated with water meadows, but much less extensive than is usual for such systems. It is difficult to see how such a small group of ditches could have actually functioned as a watermeadow since the highest section of ditch is actually above the level of the By Brook. Smith refers to springs in the field either side of the area where he had worked for Northey. A spring is shown on the 1st edition 25” OS map of 1886 in the field to the west, but no stream issues from it, and the construction of the railway and Middlehill tunnel, which at this point is close to the level of the spring lines, may very well have obliterated other springs and affected the local hydrology. Are the ditches remnants of an attempt to create a water meadow that was abandoned for some reason and which Smith was called in to sort out? Or is it more likely that these features were inserted in order to drain a low-lying area of land? Or did the work for Northey take place somewhere else, perhaps in the area around the Northey Arms and the former station and stone yard, where any traces of Smith’s endeavours will have been obliterated by subsequent activity? The hypothesis advanced here must be regarded as tentative at best, and the author would welcome any alternative explanations of the Ash Meade features. In the absence of further evidence, we can but speculate, and wonder whether Northey ever paid his debt.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Professor Emeritus Hugh Torrens, the leading authority on William Smith, and Kathleen Diston, Head of Print and Digital Collections at Oxford University Museum of Natural History, for assisting with information and access to material. The transcription of Smith’s letter to William Northey, however, and any errors in deciphering Smith’s handwriting, are my own.

References

[1] Northeys of Box and http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/Northeys3.html .

[2] Simon Winchester’s popular account The map that changed the world (2001) has helped to bring William Smith from relative obscurity.

[3] http://www.strata-smith.com reproduces all Smith’s geological maps along with other information.

[4] HS Torrens (2016), William Smith 91769-1839): his struggles as a consultant, in both geology and engineering, to simultaneously earn a living and finance his scientific projects, to 1820, Earth Sciences History 35.1, 1-46(doi: 10.17704/1944-6187-35.1.1).

[5] Had Smith been in trade he could have declared bankruptcy, but as he was taken to be ‘in business’ (ie not making a living through buying and selling) his insolvency was dealt with by an Insolvent Debtors’ Court; his imprisonment in the King’s Bench Prison only lasted a few weeks since the forfeiture of Smith’s property in Bath had satisfied his principle creditor. (Torrens 2016 loc cit, 37)

[6] Smith’s foreman was called Jonathan Crook, but the person referred to here must be Thomas Crook whose estates at Tytherton, near Chippenham, Smith had drained in 1800 (HS Torrens 2004, The water-related work of William Smith (1769-1839) , in JD Mather (ed) 200 Years of British Hydrogeology. Geological Society Special Publications 225, 15-30.). Thomas Crook was an agricultural innovator, who experimented with using steamed potatoes instead of corn as fodder for his oxen (T Davis (1794) General View of the Agriculture of Wiltshire, 53). It was through Crook that Smith was introduced to Thomas Coke, later Earl of Leicester, the great agriculturalist of Holkham, Norfolk, and via Coke to other wealthy clients, many of whom were keen exponents of the contemporary enthusiasm for agricultural improvement, including the Duke of Bedford, who employed Smith to drain his estates around Woburn (and who actually seems to have settled his bills!).

[7] Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUNMH) William Smith collection WS/C/2/0/277.

[8] Torrens (2004) loc cit, 21-23.

[9] OUNMH WS/B/002 to 007

[10] E Crittall (ed) (1952) Andrews’ and Dury’s Map of Wiltshire, 1773: A Reduced Facsimile (Wiltshire Record Society, Devizes) (http://www.wiltshirerecordsociety.org.uk/publications/1773-map-of-wiltshire/ )

[11]'Roads', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 4, ed. Elizabeth Crittall (London, 1959), pp. 254-271. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol4/pp254-271 [accessed 30 April 2018].

[12] The view may have been broadly comparable to that observed from an eastbound National Express Coach today.

[13] The processing of the images presented here follow the methods described in Ž Kokalj and R Hesse (2017) Airborne Laser Scanning Raster Visualization (Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana) (https://iaps.zrc-sazu.si/sites/default/files/pkc014_kokalj.pdf). For the technically-minded, the lidar components of the images accompanying this note have been created from the open data available from the Environment Agency using Relief Visualisation Toolbox and imported into QGIS; both RVT and QGIS are freely available open-source software.

[1] Northeys of Box and http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/Northeys3.html .

[2] Simon Winchester’s popular account The map that changed the world (2001) has helped to bring William Smith from relative obscurity.

[3] http://www.strata-smith.com reproduces all Smith’s geological maps along with other information.

[4] HS Torrens (2016), William Smith 91769-1839): his struggles as a consultant, in both geology and engineering, to simultaneously earn a living and finance his scientific projects, to 1820, Earth Sciences History 35.1, 1-46(doi: 10.17704/1944-6187-35.1.1).

[5] Had Smith been in trade he could have declared bankruptcy, but as he was taken to be ‘in business’ (ie not making a living through buying and selling) his insolvency was dealt with by an Insolvent Debtors’ Court; his imprisonment in the King’s Bench Prison only lasted a few weeks since the forfeiture of Smith’s property in Bath had satisfied his principle creditor. (Torrens 2016 loc cit, 37)

[6] Smith’s foreman was called Jonathan Crook, but the person referred to here must be Thomas Crook whose estates at Tytherton, near Chippenham, Smith had drained in 1800 (HS Torrens 2004, The water-related work of William Smith (1769-1839) , in JD Mather (ed) 200 Years of British Hydrogeology. Geological Society Special Publications 225, 15-30.). Thomas Crook was an agricultural innovator, who experimented with using steamed potatoes instead of corn as fodder for his oxen (T Davis (1794) General View of the Agriculture of Wiltshire, 53). It was through Crook that Smith was introduced to Thomas Coke, later Earl of Leicester, the great agriculturalist of Holkham, Norfolk, and via Coke to other wealthy clients, many of whom were keen exponents of the contemporary enthusiasm for agricultural improvement, including the Duke of Bedford, who employed Smith to drain his estates around Woburn (and who actually seems to have settled his bills!).

[7] Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUNMH) William Smith collection WS/C/2/0/277.

[8] Torrens (2004) loc cit, 21-23.

[9] OUNMH WS/B/002 to 007

[10] E Crittall (ed) (1952) Andrews’ and Dury’s Map of Wiltshire, 1773: A Reduced Facsimile (Wiltshire Record Society, Devizes) (http://www.wiltshirerecordsociety.org.uk/publications/1773-map-of-wiltshire/ )

[11]'Roads', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 4, ed. Elizabeth Crittall (London, 1959), pp. 254-271. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol4/pp254-271 [accessed 30 April 2018].

[12] The view may have been broadly comparable to that observed from an eastbound National Express Coach today.

[13] The processing of the images presented here follow the methods described in Ž Kokalj and R Hesse (2017) Airborne Laser Scanning Raster Visualization (Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana) (https://iaps.zrc-sazu.si/sites/default/files/pkc014_kokalj.pdf). For the technically-minded, the lidar components of the images accompanying this note have been created from the open data available from the Environment Agency using Relief Visualisation Toolbox and imported into QGIS; both RVT and QGIS are freely available open-source software.