|

Sheep Dips & Wagon Washes Alan Payne April 2023 In recent decades, we would scarcely recognise how Box was deeply rural throughout most of its history. The roadways were in regular agricultural use for the transport of dung heaps as the excrement was needed for fertilising the soil. In dry periods, carts loaded with hay, straw or other animal feeds would clog the streets as the horses attempted to pull heavy loads up Box’s steep hillsides. Box was particularly suitable for animal husbandry. Small enclosed fields housed flocks of sheep and small herds of cows and the movement of animals on roads and droving tracks was a regular occurrence. Considerable infrastructure was needed to support the level of animal farming and the purpose of this article is to discover the remnants of that activity which still exist but have been overlooked in the village. Sheep dip pond at Box Bottom (courtesy Carol Payne) |

Sheep Washes in Box

The immersing of sheep in rural villages was a common sight for centuries. In 2001 the Cotswold Wardens identified six sites in Box parish based on historic maps and placename evidence.[1] These were listed at 837710 (possibly Drewetts), 832679 (adjacent to Hazelbury Manor), 827679 (Washwells) and 828681 (Thornwood, Hazelbury Hill), but I could not find the exact locations of these sites. This early work was refined by Derek Hurst for the Cotswold Sheepwashes Project in 2003.[2]. He differentiated early "sheep washing" with later "sheep dipping", asserting that the former was to assist the shearing process and to give a better quality (and higher value) fleece. Local washes were usually manmade in dressed stone and could be round or square. A wash at 38370 17100 at Weavern Farm was identified as extant, circular and that at 38320 16790 at Hazelbury Hill as demolished.

The earliest placename site identified in Box is at Washwells, which is marked on Allen's 1626 and 1630 maps and referred to in 1655 in a Declaration of Trust by George Speke which mentions two holdings called Chapmans Washwells and Butchers Washwells. The Washwell lagoons appear to be restored later as a garden feature but the name of the hamlet suggests a more specific, agricultural origin. It is possible that the hillside enabled flocks of animals to be driven through water of different purity and its central location allowed large numbers of sheep to be treated at the same time.

The immersing of sheep in rural villages was a common sight for centuries. In 2001 the Cotswold Wardens identified six sites in Box parish based on historic maps and placename evidence.[1] These were listed at 837710 (possibly Drewetts), 832679 (adjacent to Hazelbury Manor), 827679 (Washwells) and 828681 (Thornwood, Hazelbury Hill), but I could not find the exact locations of these sites. This early work was refined by Derek Hurst for the Cotswold Sheepwashes Project in 2003.[2]. He differentiated early "sheep washing" with later "sheep dipping", asserting that the former was to assist the shearing process and to give a better quality (and higher value) fleece. Local washes were usually manmade in dressed stone and could be round or square. A wash at 38370 17100 at Weavern Farm was identified as extant, circular and that at 38320 16790 at Hazelbury Hill as demolished.

The earliest placename site identified in Box is at Washwells, which is marked on Allen's 1626 and 1630 maps and referred to in 1655 in a Declaration of Trust by George Speke which mentions two holdings called Chapmans Washwells and Butchers Washwells. The Washwell lagoons appear to be restored later as a garden feature but the name of the hamlet suggests a more specific, agricultural origin. It is possible that the hillside enabled flocks of animals to be driven through water of different purity and its central location allowed large numbers of sheep to be treated at the same time.

The structures were man made, built in ashlar stone at some considerble expense (photos below courtesy Carol Payne)

Sheep Dips

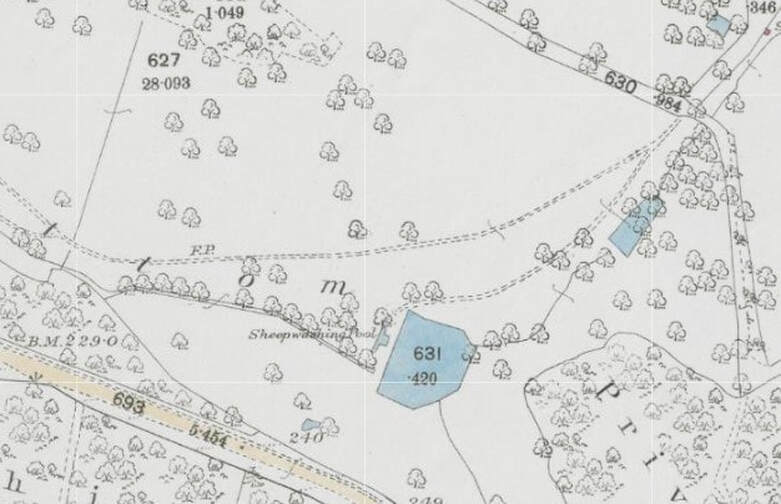

The creation of sheep dips after the mid-1800s served a different purpose to immerse animals in a treated solution to protect them from infestations of parasites such as blow-fly and lice. The process was revolutionised with the discovery of insecticides to kill the eggs and lava of the parasite mites. The dips were usually much smaller sites than washes for fear that the toxic substances would escape into drinking water needed for human activity. As a result low lying and obscure locations in Box were most suitable for creating sheep dips.

The sheep dip in the woods at Box Bottoms still exists with a feeder pond collecting water (headline photo). This supplied a small site in which the sheep could be controlled as they were dipped. The dip was still in use in the 1952 when local residents recalled that there were two metal gates for shepherds to push down into water and immerse the sheep.[3]

The creation of sheep dips after the mid-1800s served a different purpose to immerse animals in a treated solution to protect them from infestations of parasites such as blow-fly and lice. The process was revolutionised with the discovery of insecticides to kill the eggs and lava of the parasite mites. The dips were usually much smaller sites than washes for fear that the toxic substances would escape into drinking water needed for human activity. As a result low lying and obscure locations in Box were most suitable for creating sheep dips.

The sheep dip in the woods at Box Bottoms still exists with a feeder pond collecting water (headline photo). This supplied a small site in which the sheep could be controlled as they were dipped. The dip was still in use in the 1952 when local residents recalled that there were two metal gates for shepherds to push down into water and immerse the sheep.[3]

Wagon Wash

Most villages had facilities for the washing of wagons and carts, usually deep ponds or fords. Probably Box had more than one to service different rural locations. They became more common in the 18th century, when four-wheeled farm wagons and two-wheeled carts were the normal husbandry method of transport for the period from the 1750s until the Second World War.[4]

The Box area needed facilities for washing farm carts and wagons to clean the excrement left on them after transporting animals and dung. This was partly connected with sheep infestation as manure in heaps and left on vehicles attracted the breeding of fly maggots which later infected the sheep flocks. In Box farm carters or wagoners still worked in many hamlets but more money could be made transporting stone and many people switched industry.

Most villages had facilities for the washing of wagons and carts, usually deep ponds or fords. Probably Box had more than one to service different rural locations. They became more common in the 18th century, when four-wheeled farm wagons and two-wheeled carts were the normal husbandry method of transport for the period from the 1750s until the Second World War.[4]

The Box area needed facilities for washing farm carts and wagons to clean the excrement left on them after transporting animals and dung. This was partly connected with sheep infestation as manure in heaps and left on vehicles attracted the breeding of fly maggots which later infected the sheep flocks. In Box farm carters or wagoners still worked in many hamlets but more money could be made transporting stone and many people switched industry.

The wagons were usually above head height with extendable sides to enable more depth of material being transported.

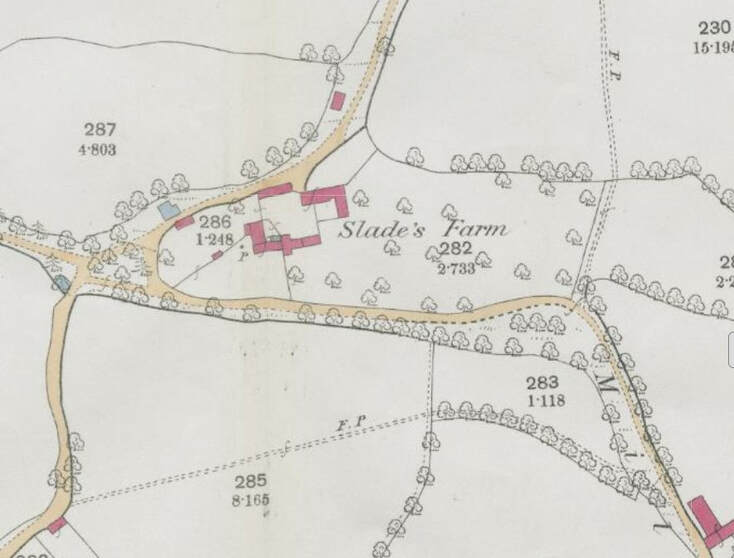

As such, cleaning was easier in deeper ponds and streams, often excavated by hand to allow greater depth. There probably were several wagon washes in the Box area but only one is still identifiable at Slades Farm, Ditteridge, as it remained in use until the 1960s.[5]

As such, cleaning was easier in deeper ponds and streams, often excavated by hand to allow greater depth. There probably were several wagon washes in the Box area but only one is still identifiable at Slades Farm, Ditteridge, as it remained in use until the 1960s.[5]

Because the parish of Box was so dramatically altered by the stone industry in the 19th century, we sometimes overlook the significance of farming on the area throughout earlier centuries. In separate articles we have reviewed the Droving Roads and the significance of Big Pool Lane. It is also important that the remnants of the infrastructure are also recorded for posterity.

References

[1] The Cotswold Wardens, published by Worcestershire County Council

[2] Derek Hurst, Survey of Sheepwash Sites in Cotswolds AONB, Reprinted by Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal, 2003, p.62-64

[3] Courtesy Anna Grayson

[4] There are some wonderful photos of farm wagons at Along the road we go - farm wagons in The Museum of English Rural Life (reading.ac.uk)

[5] Courtesy Bob Hancock

[1] The Cotswold Wardens, published by Worcestershire County Council

[2] Derek Hurst, Survey of Sheepwash Sites in Cotswolds AONB, Reprinted by Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal, 2003, p.62-64

[3] Courtesy Anna Grayson

[4] There are some wonderful photos of farm wagons at Along the road we go - farm wagons in The Museum of English Rural Life (reading.ac.uk)

[5] Courtesy Bob Hancock