Rudloe Park Alan Payne October 2022

There are great difficulties trying to write the story of houses in Rudloe, partly because they were unnamed for many years and then regularly swapped names. For example, a property called “Rudloe House” in 1880s is not the same building as one a few hundred yards away in Leafy Lane called by the same name in the 1980s. For the avoidance of doubt, this is the story of the property at the brow of Box Hill on the junction of the A4 road and Leafy Lane. The difficulty of identifying the house is that owners have used a variety of names: Rudloe House, Rudloe College, Rudloe Towers, Sherbrooke, Rudloe Hall, Rudloe Park and Rudloe Arms– all the same property. Where there is any confusion, I have used the name Rudloe Park to identify this building.

Origins of the House

Before Rudloe Park was built, Robert Pictor, quarry-master, and his family were living at Boxfield Farm. He had taken over control of his father’s stone firm Pictor & Sons in 1857 and had developed the business to become an extremely wealthy man. The 1861 census describes him at Boxfield Farm, Boxfield Quarries: farmer of 150 acres employing 5 men and 3 boys, stone merchant employing 52 men and 10 boys and builder 9 men and 3 boys. In 1867 we can see that he had a small estate at Boxfields Farm when he advertised for a shepherd, offering candidates a cottage and garden.[1]

When Robert Pictor died suddenly on 11 February 1877, the residents of Box were shocked. He was only 46 years old and died in particularly melancholy circumstances.[2] The coroner reported that he had gone out for a walk at 6.30 pm on Sunday evening, paused to speak to a shepherd who was lambing ewes and walked away in the direction of the Bradford Road but was never seen alive after. His body was found at 6am the following day, lying in a ditch close to the mansion he was having built.[3] In 1877 the Independent Order of Good Templars (the teetotal movement based at Box Hill Methodist Church) expressed their sympathy for the death of their late esteemed and worthy brother Mr R Pictor of Rudloe House.[4]

Robert had died without making a will and there is anecdotal evidence that Rudloe House had to be sold after the intestacy had been resolved in order to clear liabilities. It is suggested that the Pictor family only rented the house afterwards and there is some evidence to support this idea. First, there is no listing whatsoever for members of the family in the 1881 census, which might suggest the house was vacant. Secondly, a strange newspaper report in the summer of 1880 states that the mansion at Box Hill built by the late Mr Robert Pictor, but which he never lived to occupy, has been let to a gentleman from Portishead who has converted it into an asylum for inebriates.[5] This makes sense following the Habitual Drunkards Act of 1879 which significantly raised prison sentences for offenders and inversely encouraged more preventative measures. It seems unlikely that the initiative went ahead and the Pictors returned to the house. As the eldest son, Herbert Robert Newman Pictor took over as head of the household after his mother’s death in 1880 and looked after the rest of the family. On 18 March 1879 Charlotte Elizabeth (Lottie) Pictor died there aged 20 and on 7 September 1886 Alice Margaret Pictor was married from there.[6]

Herbert was recorded living at Rudloe House in later censuses but we can see how his life was changing. In the 1891 census, rather strangely, he called himself retired stone merchant (aged 38 years), living with his wife Julia, two daughters and a housemaid and cook. Herbert’s marriage appears to have been breaking down by the late 1880s but he concealed these problems from the outside world. He wanted to maintain the appearance of normality and continued to cultivate the extensive gardens and grounds surrounding the property. In 1892 a garden employee, 38-year-old Nathaniel Wilkins, met with an accident as a carter when using a steam chaff cutter, which resulted in the amputation of both his hands above the wrist.[7] Herbert continued to pay his wages and donated to a fundraising initiative to fund artificial hands for Nathaniel.[8]

Before Rudloe Park was built, Robert Pictor, quarry-master, and his family were living at Boxfield Farm. He had taken over control of his father’s stone firm Pictor & Sons in 1857 and had developed the business to become an extremely wealthy man. The 1861 census describes him at Boxfield Farm, Boxfield Quarries: farmer of 150 acres employing 5 men and 3 boys, stone merchant employing 52 men and 10 boys and builder 9 men and 3 boys. In 1867 we can see that he had a small estate at Boxfields Farm when he advertised for a shepherd, offering candidates a cottage and garden.[1]

When Robert Pictor died suddenly on 11 February 1877, the residents of Box were shocked. He was only 46 years old and died in particularly melancholy circumstances.[2] The coroner reported that he had gone out for a walk at 6.30 pm on Sunday evening, paused to speak to a shepherd who was lambing ewes and walked away in the direction of the Bradford Road but was never seen alive after. His body was found at 6am the following day, lying in a ditch close to the mansion he was having built.[3] In 1877 the Independent Order of Good Templars (the teetotal movement based at Box Hill Methodist Church) expressed their sympathy for the death of their late esteemed and worthy brother Mr R Pictor of Rudloe House.[4]

Robert had died without making a will and there is anecdotal evidence that Rudloe House had to be sold after the intestacy had been resolved in order to clear liabilities. It is suggested that the Pictor family only rented the house afterwards and there is some evidence to support this idea. First, there is no listing whatsoever for members of the family in the 1881 census, which might suggest the house was vacant. Secondly, a strange newspaper report in the summer of 1880 states that the mansion at Box Hill built by the late Mr Robert Pictor, but which he never lived to occupy, has been let to a gentleman from Portishead who has converted it into an asylum for inebriates.[5] This makes sense following the Habitual Drunkards Act of 1879 which significantly raised prison sentences for offenders and inversely encouraged more preventative measures. It seems unlikely that the initiative went ahead and the Pictors returned to the house. As the eldest son, Herbert Robert Newman Pictor took over as head of the household after his mother’s death in 1880 and looked after the rest of the family. On 18 March 1879 Charlotte Elizabeth (Lottie) Pictor died there aged 20 and on 7 September 1886 Alice Margaret Pictor was married from there.[6]

Herbert was recorded living at Rudloe House in later censuses but we can see how his life was changing. In the 1891 census, rather strangely, he called himself retired stone merchant (aged 38 years), living with his wife Julia, two daughters and a housemaid and cook. Herbert’s marriage appears to have been breaking down by the late 1880s but he concealed these problems from the outside world. He wanted to maintain the appearance of normality and continued to cultivate the extensive gardens and grounds surrounding the property. In 1892 a garden employee, 38-year-old Nathaniel Wilkins, met with an accident as a carter when using a steam chaff cutter, which resulted in the amputation of both his hands above the wrist.[7] Herbert continued to pay his wages and donated to a fundraising initiative to fund artificial hands for Nathaniel.[8]

|

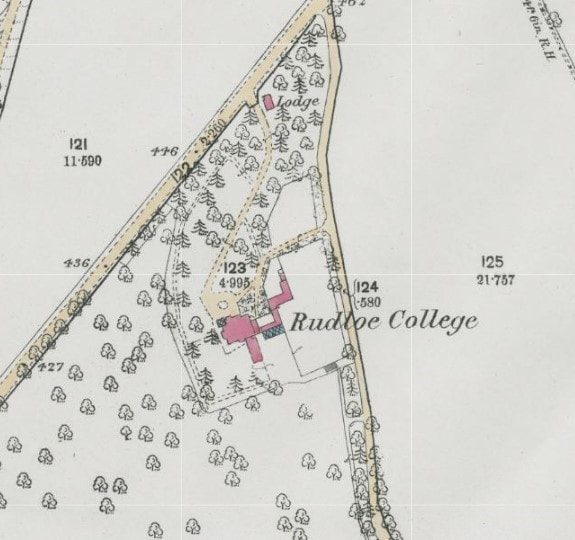

Rudloe College As his wife and children spent more time away from Box, Herbert did not need all of the rooms and parts of the house were let out separately from the Pictor family, becoming a school called Rudloe College. Rudloe College was described as the former Corsham School in 1887, referred to as a first-grade public school with junior and senior departments under the direction of CH Hulls and Rev W Mathias.[9] At times it called itself High class Church of England School for sons of Gentlemen offering a navy department in the junior school and army department in the senior school.[10] The location of the college was given as near a road leading from Corsham to Bath with the lodge of the college adjoining the road on the left-hand side.[11] Ordnance Survey showing Rudloe College (courtesy Know Your Place) |

In 1886 the college claimed to have 20 pupils and put out full sides to play football, rugby and cricket matches, including a match against a Box Cricket Club.[12] Some football matches featured the sons of the Pictor family, Norman and Bernard Douglas Pictor, children of William Smith Pictor of Pickwick Villa.[13] In October 1886 Herbert and Julia Pictor assisted in the College’s Annual Sports day acting as starters and offering material aid in more ways than one, the nature of which is uncertain, presumably financial help.[14]

A marketing blitz by the school to attract more pupils in 1885 and 1886 was countered by a legal case in 1887 brought by Charles Henry Hulls against Rev W Mathias. Rev Mathias had attempted to buy out ownership of the college for £2,500 but failed to pay some instalments claiming that Hulls had misrepresented the number of pupils and rental income of the school.[15] Rev Mathias later agreed to pay the outstanding sum.[16] There were other problems. In December 1888 Theophil Hanhart, aged 24, a French and German master at the college admitted to the notorious Whitechapel murders, known as the Jack the Ripper murders.[17] Rev Mathias went to Shoreditch, London and spoke up for Theophil, a German national. Mathias said that he had been with the prisoner at the time of the murders and Theophil was suffering from delusions, brought on by over-study. Theophil was found to be deranged and taken to a secure infirmary.

The end was in sight and Rev Mathias left Box in August 1890 selling the carriages, agricultural and grounds equipment.[18]

The school furniture and furnishings were sold separately, including desks, dining tables sufficient to seat 60 people,

40 bedsteads, gymnasium, sports and theatrical equipment.[19] Rev Mathias claimed that he left because his lease had expired and moved to Isabella Place, Combe Down, Bath, where his son Charles Arthur Stirling Mathias was born. Between at least 1892 and 1894 Mrs Jessie Hesseltine Taylor of Rudloe Tower, Box, Wilts, widow of John Taylor, owner of The Rocks, Marshfield was occupying the house or parts of it.[20]

A marketing blitz by the school to attract more pupils in 1885 and 1886 was countered by a legal case in 1887 brought by Charles Henry Hulls against Rev W Mathias. Rev Mathias had attempted to buy out ownership of the college for £2,500 but failed to pay some instalments claiming that Hulls had misrepresented the number of pupils and rental income of the school.[15] Rev Mathias later agreed to pay the outstanding sum.[16] There were other problems. In December 1888 Theophil Hanhart, aged 24, a French and German master at the college admitted to the notorious Whitechapel murders, known as the Jack the Ripper murders.[17] Rev Mathias went to Shoreditch, London and spoke up for Theophil, a German national. Mathias said that he had been with the prisoner at the time of the murders and Theophil was suffering from delusions, brought on by over-study. Theophil was found to be deranged and taken to a secure infirmary.

The end was in sight and Rev Mathias left Box in August 1890 selling the carriages, agricultural and grounds equipment.[18]

The school furniture and furnishings were sold separately, including desks, dining tables sufficient to seat 60 people,

40 bedsteads, gymnasium, sports and theatrical equipment.[19] Rev Mathias claimed that he left because his lease had expired and moved to Isabella Place, Combe Down, Bath, where his son Charles Arthur Stirling Mathias was born. Between at least 1892 and 1894 Mrs Jessie Hesseltine Taylor of Rudloe Tower, Box, Wilts, widow of John Taylor, owner of The Rocks, Marshfield was occupying the house or parts of it.[20]

William Littlejohn Philip

Of all the notable people who have lived in Box, none can be more remarkable than William Littlejohn Philip (12 February 1863-20 July 1951) who lived in the house between 1902 and 1912. He was a colossus in his achievements and, although similar in beliefs to Herbert Pictor, their lives panned out totally differently. William Philip tenanted the property after his retirement as managing director of an engineering firm in Glasgow in March 1902, renaming the building Sherbrooke House, so called after the street in Glasgow where he grew up.[21] He continued to work as the managing director of a local engineering firm, Spencer & Co Limited at their premises in Melksham.

William was the son of a large Scottish family, all members of the United Free Church of Scotland and many of them ministers. During the 1900s William was chairman of the Bath Presbyterian Church Building Committee and instrumental in converting the Trinity Presbyterian Church at Brock Street, once an Anglican chapel-of-ease.[22] It was opened by the Dowager Lady Tweedmouth in June 1904.[23] He became treasurer of the Bath Presbyterian Church and was responsible for clearing many of the debts incurred in the acquisition and restoration of the church.

Of all the notable people who have lived in Box, none can be more remarkable than William Littlejohn Philip (12 February 1863-20 July 1951) who lived in the house between 1902 and 1912. He was a colossus in his achievements and, although similar in beliefs to Herbert Pictor, their lives panned out totally differently. William Philip tenanted the property after his retirement as managing director of an engineering firm in Glasgow in March 1902, renaming the building Sherbrooke House, so called after the street in Glasgow where he grew up.[21] He continued to work as the managing director of a local engineering firm, Spencer & Co Limited at their premises in Melksham.

William was the son of a large Scottish family, all members of the United Free Church of Scotland and many of them ministers. During the 1900s William was chairman of the Bath Presbyterian Church Building Committee and instrumental in converting the Trinity Presbyterian Church at Brock Street, once an Anglican chapel-of-ease.[22] It was opened by the Dowager Lady Tweedmouth in June 1904.[23] He became treasurer of the Bath Presbyterian Church and was responsible for clearing many of the debts incurred in the acquisition and restoration of the church.

|

He was a great philanthropist, chairman of the London Missionary Society and in 1901 bought 14 acres of land at Beanacre Road, Melksham with the intention that working men might erect their own homes and some plots kept for William to build houses.[24] Notwithstanding his own religious views he made frequent donations to the maintenance of Box Church and to support unemployed men in the parish.[25] His interests were ubiquitous including leasing the Garrick Theatre, London, where he financed various plays.[26]

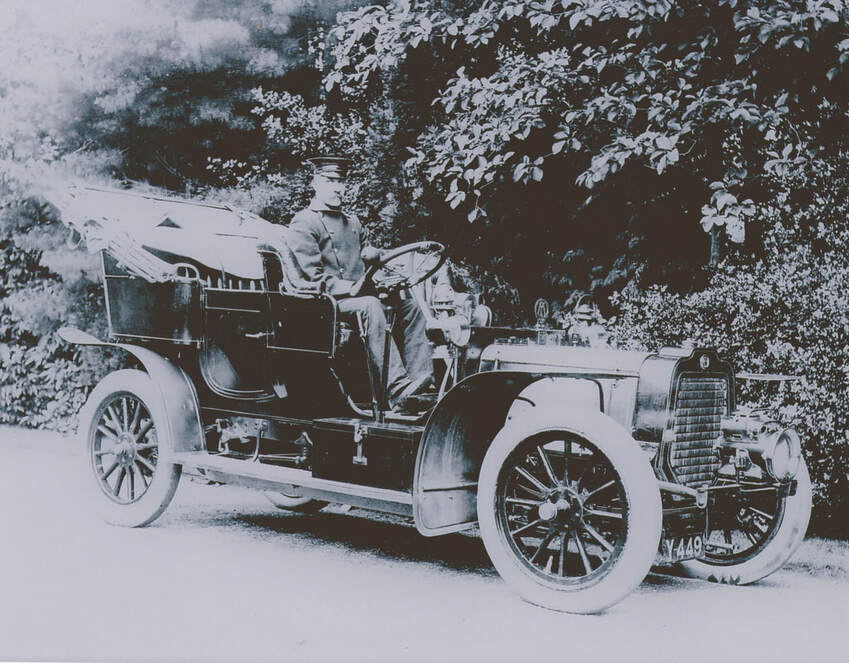

William and his wife Margaret Smith Briggs, eldest daughter of William Briggs of Melksham, were close friends of Charles Oatley and his wife Hilda. In 1907 they put on entertainment and a sumptuous tea for elderly Box Hill residents at the Box Hill chapel schoolroom.[27] In addition, they were both avid supporters of Technical Education and William was a regular lecturer in a variety of subjects, including talks on items such as The Atmosphere, to classes in Melksham and Hilperton. His particular skill was with mechanical appliances of the handling, transport and unloading of goods.[28] |

After the insolvency of Herbert Pictor in 1907, William took his place on the Wiltshire County Council, defeating Dr James Pirie Martin by 148 votes, and was proposed as a vice-president of the Corsham Liberal Club.[29] In 1908 he was appointed a magistrate.[30] By February 1908 he became chairman of the Council’s Finance, Law and Parliamentary Committee and the Unemployed Workmen Compensation Committee.[31] More Council work followed, including the Small Holdings and Allotments Committee.[32]

At home, William was a keen gardener and appointed Henry Oatley Woodman to care for the grounds. They won various horticultural prizes for their produce including tuberous begonias.[33] In 1909 the gardens at Sherbrooke were described as plantations in which there was a shrubbery known as barberry. They were planted some years ago and had reached considerable perfection. They were a source of great beauty during winter months and early spring.[34] William was still living at Sherbrooke House in June 1911 when he proposed Joseph Fry for a position on the Rural District Council, whose nomination was seconded by Herbert Pictor’s uncle Cornelius at Fogleigh House.[35] In the 1911 census, William was alone in the 25-roomed house except for Sidney Edward Aust, farm labourer who attends to cows and poultry.

As a brief aside, William’s career continued long after he left Box in 1912 and moved to Strathavon, Melksham, a house he had also rented since 1907.[36] The King and Queen visited his Melksham factory on a tour of the West Country in 1917 during the First World War and spoke to the 300 female munitions workers there. They were obviously impressed with the munitions being made there on machines designed by William.[37] William’s innovation was the use of hydraulic lifts for work on heavy metal parts. Using the technology, the munitions factory could employ female labour to work on heavy shell cases and William was appointed an OBE in 1919 for his contribution to the war effort.[38]

At home, William was a keen gardener and appointed Henry Oatley Woodman to care for the grounds. They won various horticultural prizes for their produce including tuberous begonias.[33] In 1909 the gardens at Sherbrooke were described as plantations in which there was a shrubbery known as barberry. They were planted some years ago and had reached considerable perfection. They were a source of great beauty during winter months and early spring.[34] William was still living at Sherbrooke House in June 1911 when he proposed Joseph Fry for a position on the Rural District Council, whose nomination was seconded by Herbert Pictor’s uncle Cornelius at Fogleigh House.[35] In the 1911 census, William was alone in the 25-roomed house except for Sidney Edward Aust, farm labourer who attends to cows and poultry.

As a brief aside, William’s career continued long after he left Box in 1912 and moved to Strathavon, Melksham, a house he had also rented since 1907.[36] The King and Queen visited his Melksham factory on a tour of the West Country in 1917 during the First World War and spoke to the 300 female munitions workers there. They were obviously impressed with the munitions being made there on machines designed by William.[37] William’s innovation was the use of hydraulic lifts for work on heavy metal parts. Using the technology, the munitions factory could employ female labour to work on heavy shell cases and William was appointed an OBE in 1919 for his contribution to the war effort.[38]

|

The innovation was equally useful for other purposes and the Melksham factory later specialised in grain elevators. William went to South Africa to advise the government on these in 1920.[39] By then he had taken residence at Westwood, Lansdown, Bath where his only daughter Margaret Jane was married. He retired from Spencer & Co in December 1922 but returned to run the business again in 1925. In 1939 he retired to Bournemouth where he lived until his death in 1951.

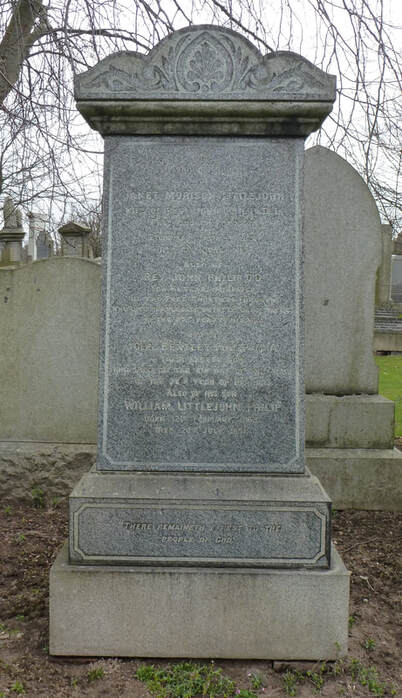

He is often considered one of Melksham’s most prestigious residents, with two streets named after him Philip Close and Littlejohn Avenue (where the 400th post-war council house was built in 1953, mirroring the 300th at Philip Close in 1951) and a firm at the heart of the town the envy of the world.[40] After such generosity throughout his life, his estate on his death only amounted to £32,485. During World War I Back with the story of Rudloe House, the Langton family came after William Littlejohn Philip left in 1912. Stephen Langton (1870-2 August 1939), his wife Adelaide and their family were wealthy occupiers of independent means (their money derived from inheritance) and I have not found any impact that they had on the property. They lived in the house throughout the First World War until 1921. Right: William Littlejohn Philip's unostentatious tombstone (courtesy GariochGraver) |

The Langtons were supporters of various activities in the village during and after the First World War. They invited 34 members of the Box Scout Troop to show their scoutcraft skills at Sherbrooke one afternoon in July 1915. The troop marched up Box Hill watched with great interest by the inhabitants and then performed drill routines and searched for articles hidden in various parts if the grounds, after which they were presented with oranges, cakes and bananas.[41] Mrs Langton was an avid fundraiser for the Red Cross during World War I and Box Commandant for the Voluntary Aid Detachment from at least 1916 until 1920.[42] Living at Sherbrooke in Voluntary Aid Detachment records of 1919-20 were Work Party Leader, Mrs Adelaide Winifred Langton, Miss Edith Ruth Hickman, Miss Beatrice W Hignett, relative of Langtons, Mrs Sarah Anne Hignett, relative, Miss Alice Ellen LeFevre. A Gingell occupied Sherbrooke Lodge as a chauffeur.

The property was sold in 1921 by CWB Oatley, auctioneer, to Major WG Southey Harrison of the 3rd King’s Hussars succeeding Stephen Langton who was moving to Reading after living there for 10 years.[43] It was described as Mansion and Park of 42 acres.[44]

The property was sold in 1921 by CWB Oatley, auctioneer, to Major WG Southey Harrison of the 3rd King’s Hussars succeeding Stephen Langton who was moving to Reading after living there for 10 years.[43] It was described as Mansion and Park of 42 acres.[44]

Montgomery Campbell at Rudloe Park

Jane Darling Leather-Culley Montgomery Campbell (1860-25 December 1930) moved to Sherbrooke and renamed the house Rudloe Park. The house was described as a mansion formerly known as Sherbrooke, situated on a commanding brow of the hill overlooking the Weavern (brook) and the Box valley.[45] Her background was that she was the daughter of George Culley of Fowberry Tower, Wooler, Northumberland, part of a famous Northumberland agricultural-improvement family.[46] She was brought up in some luxury with eight servants in the house. She married her first husband Arthur Hugo Leather (1846-1924) in 1878 when she was 18 years old and he was 32, after which the family line was called Leather-Culley. The family sold their entire Northumberland estates in 1920 and Arthur died in 1924.

However, Jane’s life story was much more exciting than this, particularly concerning her bravery during the Boer War. She left her family home and, accompanied by her maid, took a 6-mule wagon to Ladybrand Hospital, near Lesotho. When the Boer army attacked in 1900, water supplies were exhausted and she ran on foot a mile and a half each way through no-man’s-land to bring water to the hospital by buckets on a yoke. For her courage, she was made a Lady of Grace of the Order of St John of Jerusalem. After she was widowed, Jane moved down to Box and on 6 November 1924 married Archibald Montgomery-Campbell (1861-21 April 1934), retired military captain, bachelor.

Jane remained active in the Red Cross and St John’s but was in poor health in the late 1920s. She was indisposed for the garden party held in the grounds in July 1925 by the Box Branch of the Women’s Union.[47] The theme of the party was Buy British Goods despite the fact that they were dearer. She died on Christmas Day in 1930 and her body was solemnly conveyed from Rudloe Park House to Box Church. The mourners included the nobility of the North Wiltshire area as well as distinguished local residents. It was a choral burial service and: As the body was borne from the Church, the “Nunc Dimittis” (usually taken to mean “Now Let Depart”) was chanted by the choir.[48]

Jane Darling Leather-Culley Montgomery Campbell (1860-25 December 1930) moved to Sherbrooke and renamed the house Rudloe Park. The house was described as a mansion formerly known as Sherbrooke, situated on a commanding brow of the hill overlooking the Weavern (brook) and the Box valley.[45] Her background was that she was the daughter of George Culley of Fowberry Tower, Wooler, Northumberland, part of a famous Northumberland agricultural-improvement family.[46] She was brought up in some luxury with eight servants in the house. She married her first husband Arthur Hugo Leather (1846-1924) in 1878 when she was 18 years old and he was 32, after which the family line was called Leather-Culley. The family sold their entire Northumberland estates in 1920 and Arthur died in 1924.

However, Jane’s life story was much more exciting than this, particularly concerning her bravery during the Boer War. She left her family home and, accompanied by her maid, took a 6-mule wagon to Ladybrand Hospital, near Lesotho. When the Boer army attacked in 1900, water supplies were exhausted and she ran on foot a mile and a half each way through no-man’s-land to bring water to the hospital by buckets on a yoke. For her courage, she was made a Lady of Grace of the Order of St John of Jerusalem. After she was widowed, Jane moved down to Box and on 6 November 1924 married Archibald Montgomery-Campbell (1861-21 April 1934), retired military captain, bachelor.

Jane remained active in the Red Cross and St John’s but was in poor health in the late 1920s. She was indisposed for the garden party held in the grounds in July 1925 by the Box Branch of the Women’s Union.[47] The theme of the party was Buy British Goods despite the fact that they were dearer. She died on Christmas Day in 1930 and her body was solemnly conveyed from Rudloe Park House to Box Church. The mourners included the nobility of the North Wiltshire area as well as distinguished local residents. It was a choral burial service and: As the body was borne from the Church, the “Nunc Dimittis” (usually taken to mean “Now Let Depart”) was chanted by the choir.[48]

In 1939 Rudloe Park owned by Major Charles F Clarke (13 December 1888-), retired British Army officer and Rudloe Park Lodge was a separate premises occupied by Leonard H Coleman, gardener in private service, and his family. The house has been operated as a hotel since 1961 known as Rudloe Park Hotel, which was the name used at the date of its Historic Buildings Listing in 1985. In the 1960s and 1970s the owners were Major Ferguson and then later Ian Overend.[49] In 2004 it was known as Rudloe Hall run by John Patrick Lindsay-Walker and his wife May Yuet Lindsay-Walker who undertook the development of a new 36-room annex block, adding to the existing 18 bedrooms. Building delays meant that the business went into administration, unable to pay its liabilities in 2010. Since 2013 the property has become a magnificent restaurant and hotel run by Marco Pierre White, the first British chef to be awarded three Michelin stars (which he later famously returned saying that the organisation was just a marketing tool). The name has changed again with the current usage to The Rudloe Arms Hotel.

The story of the house is as varied as the number of name changes. What remains true is that the owners and occupiers of the property are some of the most interesting residents ever in the history of Box.

References

[1] The Wiltshire Independent, 17 October 1867

[2] Bristol Mercury and Western Counties Advertiser, 17 February 1877

[3] North Wilts Herald, 19 February 1877

[4] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 24 February 1877

[5] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 July 1880

[6] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 20 March 1879 and Berkshire Chronicle, 11 September 1886

[7] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 1 December 1892

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 2 March 1893

[9] Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, 12 September 1885

[10] Bristol Times and Mirror, 16 December 1885

[11] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 12 April 1888

[12] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 15 April 1886 and Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 15 April 1886, 1 July 1886 and 24 November 1887

[13] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 11 November 1886 and 28 June 1888

[14] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 21 October 1886

[15] North Wilts Herald, 21 January 1887

[16] The Somerset Standard, 22 January 1887

[17] South Wales Echo, 24 December 1888

[18] Western Daily Press, 26 July 1890

[19] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 28 August 1890

[20] Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, 25 November 1892 and Western Daily Press, 4 January 1894

[21] Clifton Society, 27 November 1902, Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 1 March 1902 and Aberdeen Press and Journal, 30 October 1899

[22] The Bath Chronicle, 12 February 1916

[23] Bristol Times and Mirror, 3 June 1904

[24] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 2 March 1901

[25] Parish Magazine, November 1903 and January 1907

[26] The Wiltshire Times, 28 July 1951

[27] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 5 January 1907

[28] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 12 August 1909

[29] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 and 21 December 1907

[30] The Salisbury Times, 3 January 1908

[31] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 22 February 1908

[32] The Salisbury Times, 20 March 1908

[33] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 12 August 1909

[34] The Wiltshire Times, 16 January 1909

[35] The Wiltshire Times, 17 June 1911

[36] The Wiltshire Times, 21 August 1920

[37] The Wiltshire Times, 17 November 1917

[38] Aberdeen Evening Express, 24 March 1939

[39] Aberdeen Weekly Journal, 10 January 1919 and The Westminster Gazette, 21 May 1920

[40] See the wonderful review of Spencer & Co in The Wiltshire Times, 10 January 1953 and The Wiltshire Times,

7 November 1953

[41] The Wiltshire Times, 3 July 1915

[42] The Wiltshire Times, 4 March 1916 and 22 July 1916

[43] The Wiltshire Times, 6 August 1921

[44] Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette 1 October 1921

[45] The Wiltshire Times, 3 January 1931

[46] Berwickshire News and General Advertiser, 26 December 1922

[47] The Wiltshire Times, 25 July 1925

[48] The Wiltshire Times, 3 January 1931

[49] Courtesy Paul Turner, Rudloe Scene

[1] The Wiltshire Independent, 17 October 1867

[2] Bristol Mercury and Western Counties Advertiser, 17 February 1877

[3] North Wilts Herald, 19 February 1877

[4] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 24 February 1877

[5] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 July 1880

[6] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 20 March 1879 and Berkshire Chronicle, 11 September 1886

[7] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 1 December 1892

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 2 March 1893

[9] Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, 12 September 1885

[10] Bristol Times and Mirror, 16 December 1885

[11] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 12 April 1888

[12] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 15 April 1886 and Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 15 April 1886, 1 July 1886 and 24 November 1887

[13] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 11 November 1886 and 28 June 1888

[14] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 21 October 1886

[15] North Wilts Herald, 21 January 1887

[16] The Somerset Standard, 22 January 1887

[17] South Wales Echo, 24 December 1888

[18] Western Daily Press, 26 July 1890

[19] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 28 August 1890

[20] Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, 25 November 1892 and Western Daily Press, 4 January 1894

[21] Clifton Society, 27 November 1902, Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 1 March 1902 and Aberdeen Press and Journal, 30 October 1899

[22] The Bath Chronicle, 12 February 1916

[23] Bristol Times and Mirror, 3 June 1904

[24] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 2 March 1901

[25] Parish Magazine, November 1903 and January 1907

[26] The Wiltshire Times, 28 July 1951

[27] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 5 January 1907

[28] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 12 August 1909

[29] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 and 21 December 1907

[30] The Salisbury Times, 3 January 1908

[31] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 22 February 1908

[32] The Salisbury Times, 20 March 1908

[33] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 12 August 1909

[34] The Wiltshire Times, 16 January 1909

[35] The Wiltshire Times, 17 June 1911

[36] The Wiltshire Times, 21 August 1920

[37] The Wiltshire Times, 17 November 1917

[38] Aberdeen Evening Express, 24 March 1939

[39] Aberdeen Weekly Journal, 10 January 1919 and The Westminster Gazette, 21 May 1920

[40] See the wonderful review of Spencer & Co in The Wiltshire Times, 10 January 1953 and The Wiltshire Times,

7 November 1953

[41] The Wiltshire Times, 3 July 1915

[42] The Wiltshire Times, 4 March 1916 and 22 July 1916

[43] The Wiltshire Times, 6 August 1921

[44] Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette 1 October 1921

[45] The Wiltshire Times, 3 January 1931

[46] Berwickshire News and General Advertiser, 26 December 1922

[47] The Wiltshire Times, 25 July 1925

[48] The Wiltshire Times, 3 January 1931

[49] Courtesy Paul Turner, Rudloe Scene