|

Herbert Robert Newman Pictor

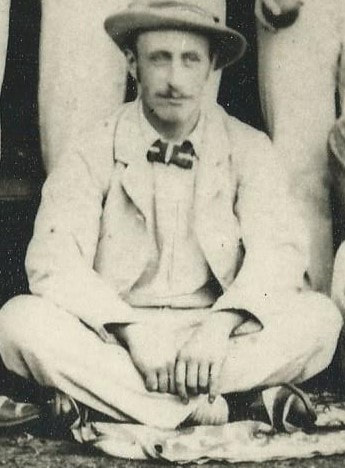

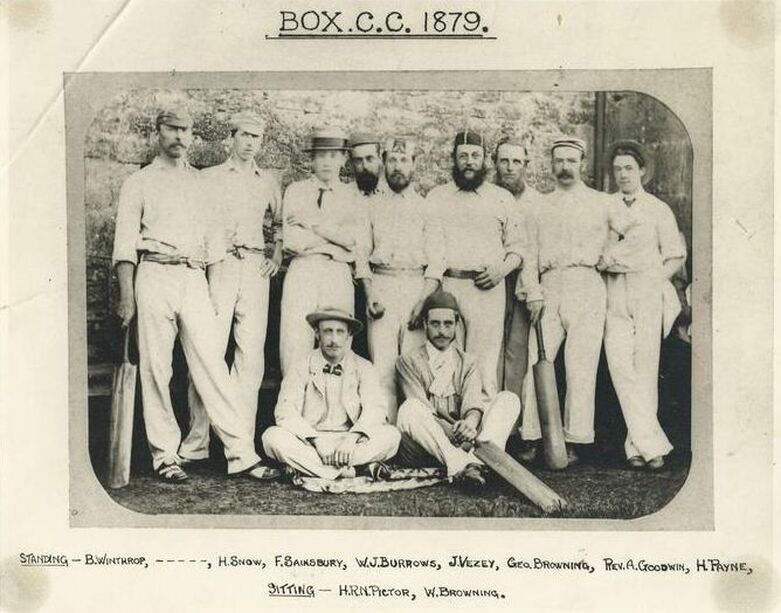

(1853-14 August 1918) Alan Payne August 2022 The most intriguing of the great houses built by the Pictor family of quarry-owners is their first, Rudloe Towers. The house was started, stopped by death, completed, tower burned down, offered for rent, had multiple names and was gardened to perfection. Even its very construction is shrouded in mystery, not really explained by its reference in the Historic Buildings Listing of Wiltshire, which says: “House built c 1875 by J Hicks of Redruth for HR Pictor, quarry owner.” The story of the house and of the involvement of Herbert Robert Newman Pictor is much more complicated than that. HRN Pictor playing for Box Cricket Club 1879 (courtesy Margaret Wakefield) |

Childhood

Herbert Robert Newman Pictor was the eldest son of Robert and Charlotte Newman Pictor, the quarry-owners who developed the greatest stone extraction firm in Box. Herbert was brought up in the company of two formidable women: his grandmother Mary Pictor and his mother Charlotte Pictor. Grandmother Mary had taken over the business of Pictor and Sons when her husband Job died suddenly in 1853 (the year of Herbert’s birth) and it was she who brought to completion the concept of the Clift Quarry tramway along Beech Road parallel to the A4. The tragedy repeated itself in 1877 when Herbert’s father, Robert Pictor, died suddenly of a heart attack whilst out on a walk on 11 February 1877. It fell to Robert’s younger brother Cornelius to take over the family business.

Herbert was 24 years old when his father died and had recently married and had a baby daughter. Deemed too young to be responsible for managing the quarry firm, Herbert was able to enjoy life playing for Box Cricket Club, as shown in the headline photograph. At the time of his father’s death Herbert and his family appear to have been still living with his parents at a house then called Boxfields Farm. Boxfields farmhouse is now called Rudloe Cottage and was probably tenanted by the Pictor family having been built by the Hartham Estate in about 1850. The family wanted to stamp their dynastic importance on the area and planned to construct a grand mansion at Rudloe Park Towers. The newspaper reports of Robert’s death make it clear that he instigated the idea for the property (at that time called Rudloe House), having submitted planning applications in 1875.[1] Probably the house was in an advanced stage of building by 1877 because the Wiltshire Temperance Lodge referred to Robert as living at Rudloe-house on 24 February 1877.[2] Robert was just 46 years of age when he was found lying in a ditch close to the mansion he was having built.[3] Robert died intestate and the probate record referred to him as living at Rudloe House.

It is often claimed that James Hicks of Redruth, Cornwall may have been the architect for the house. The design is reminiscent of several other buildings he was working on at the time.[4] As well as private houses, James Hicks was renowned for his designs of public buildings including libraries, a cathedral and primary schools. We know that Hicks was working in the area at this time because Box School was designed and completed by him in 1875 and he was the architect of Fogleigh House,

built for Robert’s brother Cornelius and completed in 1881.[5]

Herbert Robert Newman Pictor was the eldest son of Robert and Charlotte Newman Pictor, the quarry-owners who developed the greatest stone extraction firm in Box. Herbert was brought up in the company of two formidable women: his grandmother Mary Pictor and his mother Charlotte Pictor. Grandmother Mary had taken over the business of Pictor and Sons when her husband Job died suddenly in 1853 (the year of Herbert’s birth) and it was she who brought to completion the concept of the Clift Quarry tramway along Beech Road parallel to the A4. The tragedy repeated itself in 1877 when Herbert’s father, Robert Pictor, died suddenly of a heart attack whilst out on a walk on 11 February 1877. It fell to Robert’s younger brother Cornelius to take over the family business.

Herbert was 24 years old when his father died and had recently married and had a baby daughter. Deemed too young to be responsible for managing the quarry firm, Herbert was able to enjoy life playing for Box Cricket Club, as shown in the headline photograph. At the time of his father’s death Herbert and his family appear to have been still living with his parents at a house then called Boxfields Farm. Boxfields farmhouse is now called Rudloe Cottage and was probably tenanted by the Pictor family having been built by the Hartham Estate in about 1850. The family wanted to stamp their dynastic importance on the area and planned to construct a grand mansion at Rudloe Park Towers. The newspaper reports of Robert’s death make it clear that he instigated the idea for the property (at that time called Rudloe House), having submitted planning applications in 1875.[1] Probably the house was in an advanced stage of building by 1877 because the Wiltshire Temperance Lodge referred to Robert as living at Rudloe-house on 24 February 1877.[2] Robert was just 46 years of age when he was found lying in a ditch close to the mansion he was having built.[3] Robert died intestate and the probate record referred to him as living at Rudloe House.

It is often claimed that James Hicks of Redruth, Cornwall may have been the architect for the house. The design is reminiscent of several other buildings he was working on at the time.[4] As well as private houses, James Hicks was renowned for his designs of public buildings including libraries, a cathedral and primary schools. We know that Hicks was working in the area at this time because Box School was designed and completed by him in 1875 and he was the architect of Fogleigh House,

built for Robert’s brother Cornelius and completed in 1881.[5]

Herbert’s Marriage, 1876

Herbert married Julia Humphries (1855-1919) from Broad Town, Wootton Bassett, Wiltshire in 1876 when she was 21. She had earlier attended school at a ladies’ seminary at The Royal Crescent, Weston-super-Mare. They had two children soon after the marriage: Kathleen born in 1877 and Muriel in 1878.

After Robert’s death in 1877, the Pictor family moved to Rudloe Towers, including Robert’s widow Charlotte, Herbert and Julia, and Herbert’s sisters Charlotte Elizabeth (who died there in 1879), Rosina Maria and Alice Margaret. In addition, there would have been a number of household staff. Twenty-three-year-old Herbert stepped up to his responsibilities as the oldest son by giving away Rosina Maria at her wedding in March 1878.[6] Significantly, Rudloe Towers was then described as the residence of the bride’s mother, implying that Charlotte was still regarded as head of the household. Charlotte died on 7 January 1880 at Rudloe Towers and Herbert was named as an executor along with his uncles, Cornelius James (head of the firm Pictor & Sons) and William Smith Pictor.

All appeared well in the late 1880s and Julia ran a refreshment stall for a bazaar in Box to raise funds for a new church organ on 6 September 1889.[7] In 1890 she was involved with Mrs Fuller of Neston Park and Mrs Dickson of Hartham Park in starting a Free Convalescent Home for women at Rudloe.[8] They had plans for 18 beds and was due to open in June 1890 but required an estimated £200 (today worth £25,000 per annum) of annual subscriptions to survive.[9] There is no known location for the Home or if it ever came into being. In the 1891 census there is a hint of problems arising. Herbert and Julia and their daughters were stated to be living at Rudloe House and Herbert’s sisters had gone. But the number of staff had reduced to a housemaid and cook and Herbert is curiously referred to as retired stone merchant, aged just 39. After this, there are no reference to Julia’s social activities in Box.

Formation of Wiltshire County Council

We can see more about Herbert’s activities at this time. As a confident, local man in his mid-thirties, Herbert stood for nomination for Box in the first Wiltshire County Council in 1889. He also stood as a Liberal representing industry and business against the farming and Conservative interest of WJ Brown of Hazelbury. He won by 408 votes to 208. He had desisted from public canvassing in the Box division for fear of causing violence by the crowds but held several indoor meetings.[10] At one of these,

at North Wraxall, he claimed his youth would favour reform of local government and that his election would show respect to working men.[11] He was supported by the established residents and employers of Box, including Edmund Storey-Maskelyne, Peter Pinchin of Box Brewery, James Vezey at the Chequers Inn, William Maslen ex-quarryman who ran the post office and stores on Box Hill, and the Lamberts, stone masons.

The council was a new beginning for local government and Herbert obviously wanted to be a part of this initiative. He had gained business knowledge running the family stone quarry firm but limited local administrative experience and it appears to be his self-confidence and belief in his local popularity that saw him through. His appointment placed him alongside many other local notable people, including the Marquis of Bath (elected first chairman), Lord Edmund Fitzmaurice, the Earl of Pembroke,

Sir Charles Hobhouse and the Earl of Suffolk and Berkshire.[12] The Liberals were the largest group in the first council, having

29 of 60 members, but they were not in a majority, being exceeded by the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists who generally supported them.[13]

Herbert was a staunch Liberal, secretary of the North West Wilts Association and president of both the Box and Colerne Liberal Clubs.[14] He was active in promoting the Liberal cause, organising and presiding over a tour of Wiltshire villages in 1890 to speak about the issues of the moment. This was primarily the issue of Irish Home rule or some form of devolved government proposed by William Gladstone, deposed Prime Minister in 1886 and leader of one wing of the Liberal Party. Herbert was a prominent speaker in the 1889 Annual Meeting of the Association.[15] Based on his speech he was elected as a vice-president of the Association. A year later, in February 1890, he spoke at a large evening meeting of the Association on Biddestone green.[16] The report of the meeting shows him as an articulate, lively debater, interrupting and getting great applause from the crowd by saying that landlord evictions had been got up by Mr Balfour (chief supporter of the Unionists in Lord Salisbury’s Conservative government). He talked about the time he had spent in Ireland which gave him an insight into the problems of the people there.

Herbert’s Life in Box

During these years, Herbert was out and about in the area. In 1897 he officiated at the Box Friendly Society Fete and Sports Day, acting as starter alongside Rev Barlow (son-in-law of George Wilbraham Northey) and the Rev William White of Box.[17]

It was a prestigious social engagement, reflecting his importance at the time. He was a Methodist in religion and generally supported the Good Templars movement at the Box Hill Methodist Chapel, where he was the Grand Worthy Lodge Deputy but he sometimes relegated those views to a general humanist approach.[18] He made clear that he was not in favour of absolute teetotalism when he allowed the consumption of Christmas beer for inmates of the Chippenham Workhouse in 1901.[19]

For many years he was instrumental in promoting technical education in Wiltshire under the authority of the Technical Instruction Act of 1889. Herbert was a member of the Wiltshire committee, whose emphasis was on providing scholarships for poorer students and grants to establish local buildings and facilities, such as the Swindon and North Wilts Technical School and provision of free tuition for teachers and pupil teachers in Salisbury. The committee promoted carpentry and wood carving, agricultural engineering, science laboratories, horticulture, and soil analysis throughout the county.[20] Herbert promoted the conversion of buildings at Clift Quarry to be called Adult House.[21]

Education was not just limited to young men, there was considerable emphasis on learning for women. They were offered instruction in cookery, hygiene and domestic science with County Council funds allocated for itinerant schools in Wiltshire, often called butter schools.[22] A butter school existed in Box in years between 1910s to 1930s, presumably operated as a night class.[23] He was in distinguished company as other committee members included the Marquis of Bath, Paul Methuen, Mr Storey-Maskelyne MP and Sir Charles Hobhouse.[24]

Meanwhile, difficulties in the amalgamated Bath Stone Firms Ltd had caused his uncle Cornelius to resign in 1899 and 46-year-old Herbert took his place. The stone industry continued to have huge peaks and troughs and the other experienced quarry-owning directors all had their own individual views, often a desire to keep the dividends paid by the firm as high as possible. Disposals of company assets was only a short-term solution and the depression in the national building trade after 1904 added to the to the problems. In 1900, Herbert was described as absent from the Bath Stone Firms' annual board meeting. He was suffering from the fashionable complaint very badly and the doctor would not allow him to leave his room.[25] This description was usually meant to imply a nervous condition.

It is probable that his marriage with Julia had broken down completely by this time. In 1901 Julia and her eldest daughter Kathleen were living outside of Box in an upmarket boarding house in Kensington, London, whilst the youngest daughter Muriel had recently married. Herbert never faced the dishonour of having a divorce from Julia but they appear to have lived separately and Julia died at Kensington in 1919.

Herbert’s Bankruptcy, November 1907

Herbert continued to perform his public duties without change as late as September 1907 and he supervised a visit of the

King and Queen to the Marquis of Lansdowne at Bowood, Chippenham in July 1907.[26] It was all a face-saving exercise and Herbert appears to have been in denial of his financial circumstances.

In November 1907 he was declared bankrupt. The Official Receiver declared his liabilities as £23,135.0s.8d and that most of his assets had been mortgaged to cover part of those debts. The property that he owned was houses in Wick Road and Trelawney Road, Brislington and at Bradford-on-Avon but there was no mention of Rudloe House. There were a few other assets, such as shares in the Forest of Dean Stone Firms Ltd but these were also mostly mortgaged. There were free assets of only £780.12s.2d and, as a result, there was a deficit of £9,906.8s.5d (now equivalent to £1.2 million).[27] Herbert attributed his insolvency to depreciation of freehold property and shares, losses on becoming guarantor for William David, now a bankrupt. William David appears to have been a fantasist who conned his way into employment as general manager with the Bath Stone Firms Ltd in 1897 and, to avoid his own liabilities, set up a complex arrangement of shareholdings for his company The Forest of Dean Stone Firms Ltd.[28] Herbert had personally guaranteed parts of the arrangement but the liability was called in when William David went bankrupt.

Herbert declared that he had only become aware of his insolvency during the last few months. By March 1908, he had moved out of Rudloe House and sold his possessions, including furniture, carpets, paintings, utensils, garden equipment, carts and five hives of bees.[29] It was a catastrophe for Herbert as well as a personal tragedy. The bankruptcy was a public humiliation as he had recently acted as the administrator of financial responsibility for the Chippenham Workhouse and the Colerne Liberal Club who sued their secretary for theft in 1904.[30]

Bankruptcy proceedings forced him to resign as the Box representative on Wiltshire County Council in November 1907, withdraw as chairman of the Chippenham Rural District Council and he ceased to be the chairman of the Box Parish Council, replaced by

Dr JP Martin.[31] It must have been devastating to lose his position on the County Council, where he had served unopposed since its formation in 1889, served as vice-chairman from 1900 until 1907 and had only been appointed chairman to succeed

Mr DP Fuller in April 1907.[32] To make matters worse, he was replaced by W Littlejohn Philip of Sherbrooke House, Rudloe,

his own house renamed.[33]

Herbert was discharged from bankruptcy in June 1908, his liabilities amounting to £1,087 and his assets £793.[34] He stated that he had no income of his own and no prospect of coming into any money under legacies. It was noted that his insolvency came from the actions of others, that it was a case of the reckless giving of guarantees when he had no means to meet them. It was a huge fall in status and in 1911 he was boarding with Henry Dancey and Henry’s daughters at 1 Fogleigh Cottages,

Box Hill, presumably renting one of their four rooms.

Herbert died on 14 August 1918, a broken man undoubtedly changed by his separation from his wife and children. It was a sad ending and one of his last acts was to resign as trustee of the Box Fountain in March 1918.[35] From the optimistic Liberal of his youth, he became isolated and depressed, which contributed to his poor judgement and his bankruptcy in 1907. It was obviously a shattering blow to his self-esteem. The newspapers dealt with the tragedy most respectfully and, throughout all the difficulties in the quarry trade, it is said that Herbert was intimately connected with Box and all its associations. He knew every

quarryman.[36] If you want a model of how to behave with dignity and self-control in the face of the deepest personal and financial humiliation, look no further than Herbert Robert Newman Pictor. In his will he left only £49.5s to his younger brother Arthur John Pictor, architect.

It is hard to get a balanced view of Herbert’s character. The idealistic young Liberal and supporter of technical education is totally different to the isolated, lonely and broken individual who deserves our sympathy. His nephews and nieces described him as not liking children. This may reflect his experiences more than his underlying character but it is significant that his daughters chose to live with their mother after the separation. What we really need is Julia’s insight into their marital breakdown and better understanding of his mental reactions in order to better understand this most complicated man.

Herbert married Julia Humphries (1855-1919) from Broad Town, Wootton Bassett, Wiltshire in 1876 when she was 21. She had earlier attended school at a ladies’ seminary at The Royal Crescent, Weston-super-Mare. They had two children soon after the marriage: Kathleen born in 1877 and Muriel in 1878.

After Robert’s death in 1877, the Pictor family moved to Rudloe Towers, including Robert’s widow Charlotte, Herbert and Julia, and Herbert’s sisters Charlotte Elizabeth (who died there in 1879), Rosina Maria and Alice Margaret. In addition, there would have been a number of household staff. Twenty-three-year-old Herbert stepped up to his responsibilities as the oldest son by giving away Rosina Maria at her wedding in March 1878.[6] Significantly, Rudloe Towers was then described as the residence of the bride’s mother, implying that Charlotte was still regarded as head of the household. Charlotte died on 7 January 1880 at Rudloe Towers and Herbert was named as an executor along with his uncles, Cornelius James (head of the firm Pictor & Sons) and William Smith Pictor.

All appeared well in the late 1880s and Julia ran a refreshment stall for a bazaar in Box to raise funds for a new church organ on 6 September 1889.[7] In 1890 she was involved with Mrs Fuller of Neston Park and Mrs Dickson of Hartham Park in starting a Free Convalescent Home for women at Rudloe.[8] They had plans for 18 beds and was due to open in June 1890 but required an estimated £200 (today worth £25,000 per annum) of annual subscriptions to survive.[9] There is no known location for the Home or if it ever came into being. In the 1891 census there is a hint of problems arising. Herbert and Julia and their daughters were stated to be living at Rudloe House and Herbert’s sisters had gone. But the number of staff had reduced to a housemaid and cook and Herbert is curiously referred to as retired stone merchant, aged just 39. After this, there are no reference to Julia’s social activities in Box.

Formation of Wiltshire County Council

We can see more about Herbert’s activities at this time. As a confident, local man in his mid-thirties, Herbert stood for nomination for Box in the first Wiltshire County Council in 1889. He also stood as a Liberal representing industry and business against the farming and Conservative interest of WJ Brown of Hazelbury. He won by 408 votes to 208. He had desisted from public canvassing in the Box division for fear of causing violence by the crowds but held several indoor meetings.[10] At one of these,

at North Wraxall, he claimed his youth would favour reform of local government and that his election would show respect to working men.[11] He was supported by the established residents and employers of Box, including Edmund Storey-Maskelyne, Peter Pinchin of Box Brewery, James Vezey at the Chequers Inn, William Maslen ex-quarryman who ran the post office and stores on Box Hill, and the Lamberts, stone masons.

The council was a new beginning for local government and Herbert obviously wanted to be a part of this initiative. He had gained business knowledge running the family stone quarry firm but limited local administrative experience and it appears to be his self-confidence and belief in his local popularity that saw him through. His appointment placed him alongside many other local notable people, including the Marquis of Bath (elected first chairman), Lord Edmund Fitzmaurice, the Earl of Pembroke,

Sir Charles Hobhouse and the Earl of Suffolk and Berkshire.[12] The Liberals were the largest group in the first council, having

29 of 60 members, but they were not in a majority, being exceeded by the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists who generally supported them.[13]

Herbert was a staunch Liberal, secretary of the North West Wilts Association and president of both the Box and Colerne Liberal Clubs.[14] He was active in promoting the Liberal cause, organising and presiding over a tour of Wiltshire villages in 1890 to speak about the issues of the moment. This was primarily the issue of Irish Home rule or some form of devolved government proposed by William Gladstone, deposed Prime Minister in 1886 and leader of one wing of the Liberal Party. Herbert was a prominent speaker in the 1889 Annual Meeting of the Association.[15] Based on his speech he was elected as a vice-president of the Association. A year later, in February 1890, he spoke at a large evening meeting of the Association on Biddestone green.[16] The report of the meeting shows him as an articulate, lively debater, interrupting and getting great applause from the crowd by saying that landlord evictions had been got up by Mr Balfour (chief supporter of the Unionists in Lord Salisbury’s Conservative government). He talked about the time he had spent in Ireland which gave him an insight into the problems of the people there.

Herbert’s Life in Box

During these years, Herbert was out and about in the area. In 1897 he officiated at the Box Friendly Society Fete and Sports Day, acting as starter alongside Rev Barlow (son-in-law of George Wilbraham Northey) and the Rev William White of Box.[17]

It was a prestigious social engagement, reflecting his importance at the time. He was a Methodist in religion and generally supported the Good Templars movement at the Box Hill Methodist Chapel, where he was the Grand Worthy Lodge Deputy but he sometimes relegated those views to a general humanist approach.[18] He made clear that he was not in favour of absolute teetotalism when he allowed the consumption of Christmas beer for inmates of the Chippenham Workhouse in 1901.[19]

For many years he was instrumental in promoting technical education in Wiltshire under the authority of the Technical Instruction Act of 1889. Herbert was a member of the Wiltshire committee, whose emphasis was on providing scholarships for poorer students and grants to establish local buildings and facilities, such as the Swindon and North Wilts Technical School and provision of free tuition for teachers and pupil teachers in Salisbury. The committee promoted carpentry and wood carving, agricultural engineering, science laboratories, horticulture, and soil analysis throughout the county.[20] Herbert promoted the conversion of buildings at Clift Quarry to be called Adult House.[21]

Education was not just limited to young men, there was considerable emphasis on learning for women. They were offered instruction in cookery, hygiene and domestic science with County Council funds allocated for itinerant schools in Wiltshire, often called butter schools.[22] A butter school existed in Box in years between 1910s to 1930s, presumably operated as a night class.[23] He was in distinguished company as other committee members included the Marquis of Bath, Paul Methuen, Mr Storey-Maskelyne MP and Sir Charles Hobhouse.[24]

Meanwhile, difficulties in the amalgamated Bath Stone Firms Ltd had caused his uncle Cornelius to resign in 1899 and 46-year-old Herbert took his place. The stone industry continued to have huge peaks and troughs and the other experienced quarry-owning directors all had their own individual views, often a desire to keep the dividends paid by the firm as high as possible. Disposals of company assets was only a short-term solution and the depression in the national building trade after 1904 added to the to the problems. In 1900, Herbert was described as absent from the Bath Stone Firms' annual board meeting. He was suffering from the fashionable complaint very badly and the doctor would not allow him to leave his room.[25] This description was usually meant to imply a nervous condition.

It is probable that his marriage with Julia had broken down completely by this time. In 1901 Julia and her eldest daughter Kathleen were living outside of Box in an upmarket boarding house in Kensington, London, whilst the youngest daughter Muriel had recently married. Herbert never faced the dishonour of having a divorce from Julia but they appear to have lived separately and Julia died at Kensington in 1919.

Herbert’s Bankruptcy, November 1907

Herbert continued to perform his public duties without change as late as September 1907 and he supervised a visit of the

King and Queen to the Marquis of Lansdowne at Bowood, Chippenham in July 1907.[26] It was all a face-saving exercise and Herbert appears to have been in denial of his financial circumstances.

In November 1907 he was declared bankrupt. The Official Receiver declared his liabilities as £23,135.0s.8d and that most of his assets had been mortgaged to cover part of those debts. The property that he owned was houses in Wick Road and Trelawney Road, Brislington and at Bradford-on-Avon but there was no mention of Rudloe House. There were a few other assets, such as shares in the Forest of Dean Stone Firms Ltd but these were also mostly mortgaged. There were free assets of only £780.12s.2d and, as a result, there was a deficit of £9,906.8s.5d (now equivalent to £1.2 million).[27] Herbert attributed his insolvency to depreciation of freehold property and shares, losses on becoming guarantor for William David, now a bankrupt. William David appears to have been a fantasist who conned his way into employment as general manager with the Bath Stone Firms Ltd in 1897 and, to avoid his own liabilities, set up a complex arrangement of shareholdings for his company The Forest of Dean Stone Firms Ltd.[28] Herbert had personally guaranteed parts of the arrangement but the liability was called in when William David went bankrupt.

Herbert declared that he had only become aware of his insolvency during the last few months. By March 1908, he had moved out of Rudloe House and sold his possessions, including furniture, carpets, paintings, utensils, garden equipment, carts and five hives of bees.[29] It was a catastrophe for Herbert as well as a personal tragedy. The bankruptcy was a public humiliation as he had recently acted as the administrator of financial responsibility for the Chippenham Workhouse and the Colerne Liberal Club who sued their secretary for theft in 1904.[30]

Bankruptcy proceedings forced him to resign as the Box representative on Wiltshire County Council in November 1907, withdraw as chairman of the Chippenham Rural District Council and he ceased to be the chairman of the Box Parish Council, replaced by

Dr JP Martin.[31] It must have been devastating to lose his position on the County Council, where he had served unopposed since its formation in 1889, served as vice-chairman from 1900 until 1907 and had only been appointed chairman to succeed

Mr DP Fuller in April 1907.[32] To make matters worse, he was replaced by W Littlejohn Philip of Sherbrooke House, Rudloe,

his own house renamed.[33]

Herbert was discharged from bankruptcy in June 1908, his liabilities amounting to £1,087 and his assets £793.[34] He stated that he had no income of his own and no prospect of coming into any money under legacies. It was noted that his insolvency came from the actions of others, that it was a case of the reckless giving of guarantees when he had no means to meet them. It was a huge fall in status and in 1911 he was boarding with Henry Dancey and Henry’s daughters at 1 Fogleigh Cottages,

Box Hill, presumably renting one of their four rooms.

Herbert died on 14 August 1918, a broken man undoubtedly changed by his separation from his wife and children. It was a sad ending and one of his last acts was to resign as trustee of the Box Fountain in March 1918.[35] From the optimistic Liberal of his youth, he became isolated and depressed, which contributed to his poor judgement and his bankruptcy in 1907. It was obviously a shattering blow to his self-esteem. The newspapers dealt with the tragedy most respectfully and, throughout all the difficulties in the quarry trade, it is said that Herbert was intimately connected with Box and all its associations. He knew every

quarryman.[36] If you want a model of how to behave with dignity and self-control in the face of the deepest personal and financial humiliation, look no further than Herbert Robert Newman Pictor. In his will he left only £49.5s to his younger brother Arthur John Pictor, architect.

It is hard to get a balanced view of Herbert’s character. The idealistic young Liberal and supporter of technical education is totally different to the isolated, lonely and broken individual who deserves our sympathy. His nephews and nieces described him as not liking children. This may reflect his experiences more than his underlying character but it is significant that his daughters chose to live with their mother after the separation. What we really need is Julia’s insight into their marital breakdown and better understanding of his mental reactions in order to better understand this most complicated man.

References

[1] Courtesy Julian Orbach, notes for revised edition of Pevsner, Architectural Guides: Buildings of England: Wiltshire

[2] Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 24 February 1877

[3] North Wilts Herald, 19 February 1877

[4] See James Hicks – Archiseek – Irish Architecture

[5] See article Fogleigh House

[6] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 30 March 1878

[7] North Wilts Herald, 6 September 1889

[8] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 17 July 1890

[9] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 24 April 1890

[10] The Wiltshire Times, 26 January 1889

[11] The Wiltshire Times, 19 January 1889

[12] Warminster and Westbury Journal, 2 February 1889

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 31 January 1889

[14] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 31 August 1895

[15] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 2 February 1889

[16] The Bristol Mercury, 12 February 1890

[17] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 August 1897

[18] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 18 May 1878

[19] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 1 December 1951

[20] Western Daily Press, 22 April 1892

[21] Warminster and Westbury Journal, 9 May 1891

[22] Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 19 September 1891

[23] Recalled by Graham Eyles

[24] Swindon Advertiser and North Wilts Chronicle, 20 June 1891

[25] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 23 March 1899

[26] Warminster & Westbury Journal, 15 June 1907

[27] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 14 November 1907

[28] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.71

[29] Western Daily Press, 21 March 1908

[30] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 3 December 1904

[31] Warminster & Westbury Journal, 7 December and 28 December 1907 and Bristol Times and Mirror, 31 December 1907

[32] Warminster & Westbury Journal, 20 April 1907

[33] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 December 1907

[34] The Bath Chronicle, 4 June 1908

[35] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 30 March 1918

[36] The Bath Chronicle, 29 March 1900

[1] Courtesy Julian Orbach, notes for revised edition of Pevsner, Architectural Guides: Buildings of England: Wiltshire

[2] Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 24 February 1877

[3] North Wilts Herald, 19 February 1877

[4] See James Hicks – Archiseek – Irish Architecture

[5] See article Fogleigh House

[6] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 30 March 1878

[7] North Wilts Herald, 6 September 1889

[8] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 17 July 1890

[9] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 24 April 1890

[10] The Wiltshire Times, 26 January 1889

[11] The Wiltshire Times, 19 January 1889

[12] Warminster and Westbury Journal, 2 February 1889

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 31 January 1889

[14] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 31 August 1895

[15] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 2 February 1889

[16] The Bristol Mercury, 12 February 1890

[17] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 August 1897

[18] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 18 May 1878

[19] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 1 December 1951

[20] Western Daily Press, 22 April 1892

[21] Warminster and Westbury Journal, 9 May 1891

[22] Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 19 September 1891

[23] Recalled by Graham Eyles

[24] Swindon Advertiser and North Wilts Chronicle, 20 June 1891

[25] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 23 March 1899

[26] Warminster & Westbury Journal, 15 June 1907

[27] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 14 November 1907

[28] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.71

[29] Western Daily Press, 21 March 1908

[30] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 3 December 1904

[31] Warminster & Westbury Journal, 7 December and 28 December 1907 and Bristol Times and Mirror, 31 December 1907

[32] Warminster & Westbury Journal, 20 April 1907

[33] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 December 1907

[34] The Bath Chronicle, 4 June 1908

[35] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 30 March 1918

[36] The Bath Chronicle, 29 March 1900