Role of Women Alan Payne July 2022

We often discuss inequalities in our modern society, especially concerning the role of women. Despite legal changes and the work of activists, there are still huge differences in the way we pay women, their opportunities at work and women’s status at work and in our institutions. We sometimes forget the importance of the stuttering improvements achieved in the inter-war years.

Suffrage in the 1918 Act

In the Great Suffrage Pilgrimage of summer 1913 more than 50,000 suffragists marched on London. Some came through Box as seen in the photograph above. In March 1918 eight months before the Armistice, the 1918 Act enfranchised all adult men and women over 30 years who paid local authority rates or were university graduates or married. It gave a vote to about 40% of women (8.4 million out of an electorate of 21 million). Ten months later women were allowed to stand for parliament but only 17 of 1,623 candidates stood in the General Election of December 1918. One was elected, the Sinn Fein candidate Constance Markiewicz, who did not take up her seat. Lady Nancy Astor became the first to do so when she was elected to her husband’s constituency at Plymouth in 1919 after he became a peer.

By July 1928 all women over the age of 21 were enfranchised, the same as men and the election a year later is sometimes called The Flapper Election. The impact of women in the election was overwhelmed by economic and political issues. In the midst of rising unemployment in the Great Depression, a Scottish Highlander, Ramsay MacDonald, led the Second Labour Government to power as a minority party needing Liberal support. Generally categorised as elderly (aged 62) and out of touch (he had founded the Labour Party with Keir Hardy three decades earlier), MacDonald’s insistence on pegging the value of the pound to the Gold Standard worsened the economic problems of the Stock Market Crash of 1929. He left the Labour Party to head a National Coalition government mostly made up of Conservatives in 1931, when the Labour Party was split and nearly wiped out in subsequent elections.

Suffrage in the 1918 Act

In the Great Suffrage Pilgrimage of summer 1913 more than 50,000 suffragists marched on London. Some came through Box as seen in the photograph above. In March 1918 eight months before the Armistice, the 1918 Act enfranchised all adult men and women over 30 years who paid local authority rates or were university graduates or married. It gave a vote to about 40% of women (8.4 million out of an electorate of 21 million). Ten months later women were allowed to stand for parliament but only 17 of 1,623 candidates stood in the General Election of December 1918. One was elected, the Sinn Fein candidate Constance Markiewicz, who did not take up her seat. Lady Nancy Astor became the first to do so when she was elected to her husband’s constituency at Plymouth in 1919 after he became a peer.

By July 1928 all women over the age of 21 were enfranchised, the same as men and the election a year later is sometimes called The Flapper Election. The impact of women in the election was overwhelmed by economic and political issues. In the midst of rising unemployment in the Great Depression, a Scottish Highlander, Ramsay MacDonald, led the Second Labour Government to power as a minority party needing Liberal support. Generally categorised as elderly (aged 62) and out of touch (he had founded the Labour Party with Keir Hardy three decades earlier), MacDonald’s insistence on pegging the value of the pound to the Gold Standard worsened the economic problems of the Stock Market Crash of 1929. He left the Labour Party to head a National Coalition government mostly made up of Conservatives in 1931, when the Labour Party was split and nearly wiped out in subsequent elections.

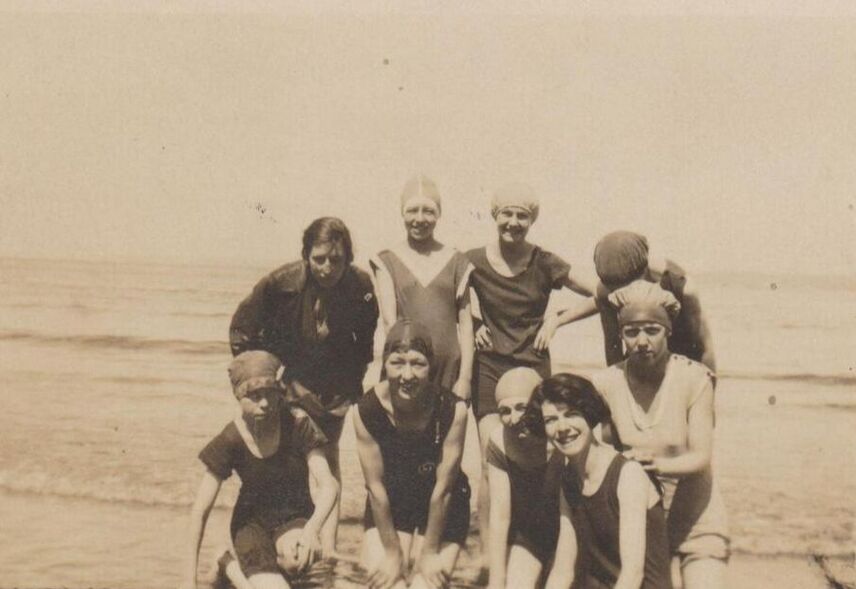

The young women of Box in the 1920s were determined to carve out a more prominent role in society (all photos courtesy Genevieve Brunt)

Women and Children’s Situation

The position of women and children in society didn’t return to exactly the same situation that existed before the First World War but changes emerged only slowly. One issue was the significance of marriage in the operation of law and the problem of children born out of wedlock. The shame of illegitimate children was still too much for an age before birth control. Until 1926 these children could only be legitimised by the marriage of their parents which would then enable them to inherit. Even when a form of social insurance was introduced in the Widows, Orphans and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act of 1925, there was an exclusion for the children of unmarried and divorced women.

Instead, women took to placing babies with relatives in informal adoption and fostering arrangements or in having them taken away from the mother. There was one other dreadful alternative seen in Box in 1924 when engine drivers working at the Railway Station noticed an object floating in the By Brook. They discovered it was the body of a newly-born baby under 10 days old weighing 7lb.[1] It was just another tragedy to be added to many similar others.

A large number of babies were born to unnamed fathers during the Great War but no particular provision was made for these in the village, the babies being absorbed into other families. Later in 1930 a home for children born to unmarried women was acquired in Box at Sunnyside Children’s Home (also known as Holy Innocents Home or By Brook House) in the 1930s.

Nursing Provision

The Box Nursing Association was formed in January 1919, staffed entirely by women.[2] It was a paid service in the years before the NHS and the Box group set out a specific scale of annual fees payable by subscription: Labourers 2s; Artisans and School Teachers 3s; Small Farmers and Tradespeople 5s; Large Farmers and Tradespeople 7s.6d; Gentry 10s. Nursing home visits required supplementary costs ranging from 1d to 2s per visit. The first nurse was Nurse Gregory who was prohibited to receive any gratuity nor take any beer or spirits. She was quickly followed by Nurse Monk.[3] Katherine Harris recalled the nurse’s visits to the Old Jockey in the 1930s: This dedicated lady ministered to the sick, the elderly and the injured in the parish, and to reach these in outlying areas she used a bicycle. After I had a particularly bad tumble the nurse came daily to our home at The Old Jockey to attend to my injured knee.[4]

The 1918-19 epidemic, sometimes called New Flu or Spanish Flu, is known to have had later waves in 1920 but there is no record of higher death rates in the village over these years and few contemporary references to the pandemic. Most of the deaths appear to be of older people, despite flu mortalities known to be higher in younger ages, particularly where malnutrition and overcrowding were prevalent. Instead, an epidemic of the virus hit the village in the winter of 1927-28, when scarcely a house in the parish has escaped the visitation of influenza.[5] Again there are no abnormal cases of death and it may have been a cautionary reference harking back to earlier waves.

Legislative Changes

A number of legal measures were introduced in the inter-war years which really show how disadvantaged women were before the twentieth century. The opportunities for women at work were improved by the 1919 Sex Discrimination Removal Act which opened up female opportunities in the civil service, university and judicial professions including acting as magistrates and jurors. In 1922, the Law of Property Act enabled a husband and wife to inherit each other's property, and also granted them equal rights to inherit the property of intestate children. The Matrimonial Causes Act 1923 allowed women to sue for divorce on the grounds of adultery and in 1925 provision was made for the payment of widows’ pensions. In 1929 a most important legal change occurred when the age of marriage for women was effectively raised from twelve to sixteen.

But there were still many areas of inequality which were not improved until after World War II, such as the dismissal of women on the occasion of their marriage by banks and in the teaching profession and the admission of female peers into the House of Lords after 1958. The influence of women in Box was seen not so much in the national, political arena but in the work of individual women.

The position of women and children in society didn’t return to exactly the same situation that existed before the First World War but changes emerged only slowly. One issue was the significance of marriage in the operation of law and the problem of children born out of wedlock. The shame of illegitimate children was still too much for an age before birth control. Until 1926 these children could only be legitimised by the marriage of their parents which would then enable them to inherit. Even when a form of social insurance was introduced in the Widows, Orphans and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act of 1925, there was an exclusion for the children of unmarried and divorced women.

Instead, women took to placing babies with relatives in informal adoption and fostering arrangements or in having them taken away from the mother. There was one other dreadful alternative seen in Box in 1924 when engine drivers working at the Railway Station noticed an object floating in the By Brook. They discovered it was the body of a newly-born baby under 10 days old weighing 7lb.[1] It was just another tragedy to be added to many similar others.

A large number of babies were born to unnamed fathers during the Great War but no particular provision was made for these in the village, the babies being absorbed into other families. Later in 1930 a home for children born to unmarried women was acquired in Box at Sunnyside Children’s Home (also known as Holy Innocents Home or By Brook House) in the 1930s.

Nursing Provision

The Box Nursing Association was formed in January 1919, staffed entirely by women.[2] It was a paid service in the years before the NHS and the Box group set out a specific scale of annual fees payable by subscription: Labourers 2s; Artisans and School Teachers 3s; Small Farmers and Tradespeople 5s; Large Farmers and Tradespeople 7s.6d; Gentry 10s. Nursing home visits required supplementary costs ranging from 1d to 2s per visit. The first nurse was Nurse Gregory who was prohibited to receive any gratuity nor take any beer or spirits. She was quickly followed by Nurse Monk.[3] Katherine Harris recalled the nurse’s visits to the Old Jockey in the 1930s: This dedicated lady ministered to the sick, the elderly and the injured in the parish, and to reach these in outlying areas she used a bicycle. After I had a particularly bad tumble the nurse came daily to our home at The Old Jockey to attend to my injured knee.[4]

The 1918-19 epidemic, sometimes called New Flu or Spanish Flu, is known to have had later waves in 1920 but there is no record of higher death rates in the village over these years and few contemporary references to the pandemic. Most of the deaths appear to be of older people, despite flu mortalities known to be higher in younger ages, particularly where malnutrition and overcrowding were prevalent. Instead, an epidemic of the virus hit the village in the winter of 1927-28, when scarcely a house in the parish has escaped the visitation of influenza.[5] Again there are no abnormal cases of death and it may have been a cautionary reference harking back to earlier waves.

Legislative Changes

A number of legal measures were introduced in the inter-war years which really show how disadvantaged women were before the twentieth century. The opportunities for women at work were improved by the 1919 Sex Discrimination Removal Act which opened up female opportunities in the civil service, university and judicial professions including acting as magistrates and jurors. In 1922, the Law of Property Act enabled a husband and wife to inherit each other's property, and also granted them equal rights to inherit the property of intestate children. The Matrimonial Causes Act 1923 allowed women to sue for divorce on the grounds of adultery and in 1925 provision was made for the payment of widows’ pensions. In 1929 a most important legal change occurred when the age of marriage for women was effectively raised from twelve to sixteen.

But there were still many areas of inequality which were not improved until after World War II, such as the dismissal of women on the occasion of their marriage by banks and in the teaching profession and the admission of female peers into the House of Lords after 1958. The influence of women in Box was seen not so much in the national, political arena but in the work of individual women.

Leading Box Women

The middle-class ladies of the village took a leading role in trying to mitigate the descent of individual families into poverty. The Box Clothing Club was started before November 1916 and was still going strong in 1930, run by Mrs Shaw Mellor.[6] There was great need in Kingsdown where coal was beyond the means of many families and the Kingsdown Coal Club, run by Mrs Lord in 1930, sought charitable donations for these families.[7]

There was also a need to educate young people who had suffered during the First World War. In the 1920s Hester Maud Fudge from the Box Post Office organised a Recreation Club in the Bingham Hall. The meeting in February 1925 featured sketches by the Box Girl Guides Troop and folk dancing by girl pupils of Box School.[8] The club continued for a long time and was still in operation in 1938.[9]

Mrs Shaw Mellor

One of the most influential Box women in the inter-war years was the Hon Mrs Shaw Mellor of Box House. She was a stalwart of the Church, the Mothers’ Union and the Women’s Institute, a pillar of the establishment. She and her husband were considerable local fundraisers with events such as the History Pageant and various church fetes. They also funded works in the village including the restoration of the Hazelbury Chapel in Box Church.[10]

One of her most impressive efforts was the creation of a new standard (banner) for the Box Mothers’ Union, which was dedicated by the Bishop of Bristol in September 1933. It was reported that the standard was embroidered by Mrs Shaw Mellor using her own wedding dress as the fabric base.

The middle-class ladies of the village took a leading role in trying to mitigate the descent of individual families into poverty. The Box Clothing Club was started before November 1916 and was still going strong in 1930, run by Mrs Shaw Mellor.[6] There was great need in Kingsdown where coal was beyond the means of many families and the Kingsdown Coal Club, run by Mrs Lord in 1930, sought charitable donations for these families.[7]

There was also a need to educate young people who had suffered during the First World War. In the 1920s Hester Maud Fudge from the Box Post Office organised a Recreation Club in the Bingham Hall. The meeting in February 1925 featured sketches by the Box Girl Guides Troop and folk dancing by girl pupils of Box School.[8] The club continued for a long time and was still in operation in 1938.[9]

Mrs Shaw Mellor

One of the most influential Box women in the inter-war years was the Hon Mrs Shaw Mellor of Box House. She was a stalwart of the Church, the Mothers’ Union and the Women’s Institute, a pillar of the establishment. She and her husband were considerable local fundraisers with events such as the History Pageant and various church fetes. They also funded works in the village including the restoration of the Hazelbury Chapel in Box Church.[10]

One of her most impressive efforts was the creation of a new standard (banner) for the Box Mothers’ Union, which was dedicated by the Bishop of Bristol in September 1933. It was reported that the standard was embroidered by Mrs Shaw Mellor using her own wedding dress as the fabric base.

Left: The Hon Mrs Shaw Mellor (courtesy Phil Martin) and Right: the Mothers' Union banner (courtesy Genevieve Brunt)

Sister Lillian Lamb

A little recorded figure was Sister Lilian Lamb in the Methodist movement. She was only in Box in the period from 1923 until the mid-1930s but was at the heart of initiatives in all the Methodist chapels during that time.[11] She had trained as a Deaconess (offering pastoral support) and converted to be an evangelist (preaching the word of God). We get an idea of her beliefs from a sermon she preached on Mothers’ Day at Bradford-on-Avon in 1934.[12] She charmed everyone with her manner and preached a powerful sermon on resisting temptation. She appealed for a restoration of the spirit of worship and for support to be given to organisations calculated to maintain peace in the world. It was a prescient warning that world peace would be challenged by the appointment of Adolph Hitler as German President as well as Chancellor in the summer of that year. It was an engagement that she repeated the following year, illustrated by incidents from her wide experience of work amongst girls in large industrial centres.[13]

Her work in Box was similarly varied, including as deaconess at Kingsdown and Box Hill Chapels. But she faced opposition as a female preacher: in some branches of United Methodism, the advent of a lady preacher was not looked upon favourably.[14]

She overcame these prejudices by her spiritual dedication and was instrumental in organising the building of the 1926 Kingsdown Methodist Church. She supported the 1930 Church Army Pageant by Rev George and Kate Foster, telling of the conversion of Wilson Carlile from businessman to slum missionary work in Westminster, London half a century earlier.[15] She was the organising secretary for the Box Methodist Church Rainbow Bazaar (urging people to hold on to hope) in 1934 which was attended by Anglicans and Methodists alike.[16] Throughout her time in Box, she preached widely and returned frequently to the village after ill-health had forced her to retire to the south coast in the 1930s. She died on 17 March 1938 was buried in Box Cemetery alongside her sister Mrs Beardwood who predeceased her.

A little recorded figure was Sister Lilian Lamb in the Methodist movement. She was only in Box in the period from 1923 until the mid-1930s but was at the heart of initiatives in all the Methodist chapels during that time.[11] She had trained as a Deaconess (offering pastoral support) and converted to be an evangelist (preaching the word of God). We get an idea of her beliefs from a sermon she preached on Mothers’ Day at Bradford-on-Avon in 1934.[12] She charmed everyone with her manner and preached a powerful sermon on resisting temptation. She appealed for a restoration of the spirit of worship and for support to be given to organisations calculated to maintain peace in the world. It was a prescient warning that world peace would be challenged by the appointment of Adolph Hitler as German President as well as Chancellor in the summer of that year. It was an engagement that she repeated the following year, illustrated by incidents from her wide experience of work amongst girls in large industrial centres.[13]

Her work in Box was similarly varied, including as deaconess at Kingsdown and Box Hill Chapels. But she faced opposition as a female preacher: in some branches of United Methodism, the advent of a lady preacher was not looked upon favourably.[14]

She overcame these prejudices by her spiritual dedication and was instrumental in organising the building of the 1926 Kingsdown Methodist Church. She supported the 1930 Church Army Pageant by Rev George and Kate Foster, telling of the conversion of Wilson Carlile from businessman to slum missionary work in Westminster, London half a century earlier.[15] She was the organising secretary for the Box Methodist Church Rainbow Bazaar (urging people to hold on to hope) in 1934 which was attended by Anglicans and Methodists alike.[16] Throughout her time in Box, she preached widely and returned frequently to the village after ill-health had forced her to retire to the south coast in the 1930s. She died on 17 March 1938 was buried in Box Cemetery alongside her sister Mrs Beardwood who predeceased her.

Conclusion

The Hon Mrs Shaw Mellor cannot be called a modern woman in any way. Rather, she followed the benevolent women who had run seventeenth century Box, Dame Rachel Speke and her mother-in-law Mrs Ann Speke. They were wealthy, deemed to be important because of their titles and no part of the emancipation of ordinary local women. In spiritual matters Sister Lillian was successful in challenging prejudice partly because her vredentials included being the godchild of William Booth (founder of the Salvation Army) and his wife Catherine. For evidence of any improvement in the status of women perhaps we need to look at the story of Mildred Brunt, who by her personal energy and enthusiasm for theatre and dance showed what women could achieve.

The Hon Mrs Shaw Mellor cannot be called a modern woman in any way. Rather, she followed the benevolent women who had run seventeenth century Box, Dame Rachel Speke and her mother-in-law Mrs Ann Speke. They were wealthy, deemed to be important because of their titles and no part of the emancipation of ordinary local women. In spiritual matters Sister Lillian was successful in challenging prejudice partly because her vredentials included being the godchild of William Booth (founder of the Salvation Army) and his wife Catherine. For evidence of any improvement in the status of women perhaps we need to look at the story of Mildred Brunt, who by her personal energy and enthusiasm for theatre and dance showed what women could achieve.

It is hard to see that the role of women was significantly improved in the 1920s and 30s. Those items that changed were bred of necessity after the agitation of the suffragists and changes in society leading to small legal improvements. Life in the inter-war period remained male-dominated with women’s roles limited by domestic duties, shop assistance and child-rearing. Social, technological and employment rights were needed before equality could be achieved and we are only just beginning to discuss some of these issues.

References

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 30 August 1924

[2] Parish Magazine, January 1919

[3] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 18 September 1920

[4] See Katherine Harris, Up Hill and Down Hill

[5] Parish Magazine, March 1928

[6] Parish Magazine, November 1916 and April 1930

[7] Parish Magazine, April 1930

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 7 February 1925

[9] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 December 1938

[10] Parish Magazine, May 1925

[11] The Wiltshire Times, 26 March 1938

[12] The Wiltshire Times, 20 October 1934

[13] The Wiltshire Times, 26 October 1935

[14] The Wiltshire Times, 26 March 1938

[15] The Wiltshire Times, 15 November 1930

[16] The Wiltshire Times, 1 December 1934

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 30 August 1924

[2] Parish Magazine, January 1919

[3] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 18 September 1920

[4] See Katherine Harris, Up Hill and Down Hill

[5] Parish Magazine, March 1928

[6] Parish Magazine, November 1916 and April 1930

[7] Parish Magazine, April 1930

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 7 February 1925

[9] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 December 1938

[10] Parish Magazine, May 1925

[11] The Wiltshire Times, 26 March 1938

[12] The Wiltshire Times, 20 October 1934

[13] The Wiltshire Times, 26 October 1935

[14] The Wiltshire Times, 26 March 1938

[15] The Wiltshire Times, 15 November 1930

[16] The Wiltshire Times, 1 December 1934