|

Religion: Its Importance in Tudor Box

Alan Payne October 2015 Nowadays we don't have many red-hot debates about religion with friends in the pub. But that wasn't the case in Tudor and Stuart Box. This article tries to explain why it happened and what people might have been discussing. The first thing to say is that the word "religion" had a slightly different meaning then. As we shall see, in Tudor and Stuart times it included certain legal and fiscal connotations which brought it to the everyday thinking of Box inhabitants. But religion was important for itself when people understood the words of the Bible preached to them in their own language for the first time and later had sufficient education to read and discuss spiritual matters with their neighbours. This article is indebted to the review and suggestions made by Martin Devon, who gave many of the more interesting anecdotes and allusions. |

The Spiritual Debate

The intensity of the theological debates was not consistent throughout the whole of this period. It was fierce during the period of the Protestant Reformation of Edward VI (1547-1553) and became most virulent in the 1640s leading into the disturbances of the Civil War and Protectorate periods.[1]

In the middle of these occurrences the Church of England, which had been established as the state religion by Elizabeth I in the Act of Uniformity of 1558-59, was generally accepted. Indeed it could be expensive not to accept because a fine of 12d was imposed on people who did not attend church at least once a week. Thereafter theological discussion became a rather vague anti-Roman Catholic feeling (against popery) such as at the time of the potential invasion by the Spanish Armada in 1588.[2] Many people in Box seem to have been unconcerned with matters of theology such as Sibill Newman who in 1592 was reprimanded for knitting during divine prayer in Box church.[3]

But this period of peace was short-lived because there were two unresolved, fundamental problems about the form that theology should take. First, any practice had to be seen to trace back to the teachings of Christ with unbroken continuity of apostolic succession (there could be no schism or new beginning in Christ's teachings). And secondly, what was to be done about the salvation of ancestors if the old beliefs were sinful? [4] Because there could be only one correct belief and the nature of that belief affected all humanity the arguments between the various religious factions became of vital concern and compromise was simply not possible.

Book of Common Prayer

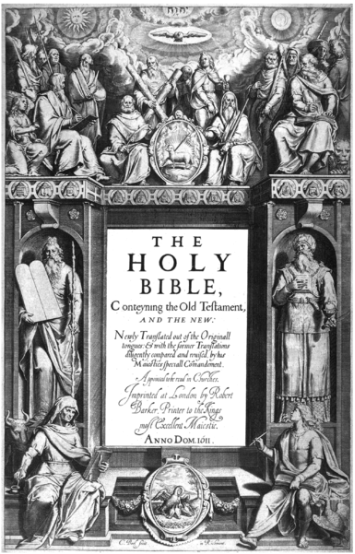

At the heart of much of the controversy was the Book of Common Prayer. This was first issued in 1549, two years after the death of Henry VIII. It was Common (universal) and referred to Praying (the congregation joining in the act of worship by reciting words in English). We now recognise passages as part of our everyday language (in sickness and in health and till death us do part) but at the time it was very controversial.

Previously, priests hidden behind the rood screen, recited the mass in an incomprehensible language, often rattling through the Latin words as quickly as possible in ten minutes. Their narrative was only interrupted by the ringing of a bell three times to indicate the moment when the bread was consecrated and miraculously became the body of Christ. The words were so misheard and not understood that the Latin words at the elevation of the Host, hoc est corpus (this is the body) have come down

to us as hocus-pocus with all that phrase implies.

After 1549 priests and laity took both bread and wine and received communion together. Preaching in English gradually began and transformed people's understanding of religion. The Book was reissued several times after the interruption of the Catholic reign of Queen Mary (1553 - 58) with more Calvinist theology but after 1572 Puritans began a more organised agitation against choirs, bishops, ceremony and Protestant rituals that they saw as still being too papist.

The Denial of 1603

On Easter Day 1603 an extraordinary event happened in Box when ordinary local people challenged the authority of Box's vicar, John Coren; his right to administer communion; the Book of Common Prayer; and the very basis of established authority in the village. It was an incident unlike anything that had gone before in Box's history. The story is easily told.

Two local residents, Christopher Butler, a weaver, and John Humphreyes, a rough mason (quarryman), organised a protest before morning prayer at St Thomas à Becket and In a tumultor sorte denydd the booke of Comon prayer & the book of the Omiles saying that there could be no edificacion for the people by them and that the unpreaching mynister could not rightly nor had noe power to administer the Sacrement.[5] That afternoon they were joined by Sylvester Butler of Castle Combe and they repeated the attack against the vicar in the churchyard.

The intensity of the theological debates was not consistent throughout the whole of this period. It was fierce during the period of the Protestant Reformation of Edward VI (1547-1553) and became most virulent in the 1640s leading into the disturbances of the Civil War and Protectorate periods.[1]

In the middle of these occurrences the Church of England, which had been established as the state religion by Elizabeth I in the Act of Uniformity of 1558-59, was generally accepted. Indeed it could be expensive not to accept because a fine of 12d was imposed on people who did not attend church at least once a week. Thereafter theological discussion became a rather vague anti-Roman Catholic feeling (against popery) such as at the time of the potential invasion by the Spanish Armada in 1588.[2] Many people in Box seem to have been unconcerned with matters of theology such as Sibill Newman who in 1592 was reprimanded for knitting during divine prayer in Box church.[3]

But this period of peace was short-lived because there were two unresolved, fundamental problems about the form that theology should take. First, any practice had to be seen to trace back to the teachings of Christ with unbroken continuity of apostolic succession (there could be no schism or new beginning in Christ's teachings). And secondly, what was to be done about the salvation of ancestors if the old beliefs were sinful? [4] Because there could be only one correct belief and the nature of that belief affected all humanity the arguments between the various religious factions became of vital concern and compromise was simply not possible.

Book of Common Prayer

At the heart of much of the controversy was the Book of Common Prayer. This was first issued in 1549, two years after the death of Henry VIII. It was Common (universal) and referred to Praying (the congregation joining in the act of worship by reciting words in English). We now recognise passages as part of our everyday language (in sickness and in health and till death us do part) but at the time it was very controversial.

Previously, priests hidden behind the rood screen, recited the mass in an incomprehensible language, often rattling through the Latin words as quickly as possible in ten minutes. Their narrative was only interrupted by the ringing of a bell three times to indicate the moment when the bread was consecrated and miraculously became the body of Christ. The words were so misheard and not understood that the Latin words at the elevation of the Host, hoc est corpus (this is the body) have come down

to us as hocus-pocus with all that phrase implies.

After 1549 priests and laity took both bread and wine and received communion together. Preaching in English gradually began and transformed people's understanding of religion. The Book was reissued several times after the interruption of the Catholic reign of Queen Mary (1553 - 58) with more Calvinist theology but after 1572 Puritans began a more organised agitation against choirs, bishops, ceremony and Protestant rituals that they saw as still being too papist.

The Denial of 1603

On Easter Day 1603 an extraordinary event happened in Box when ordinary local people challenged the authority of Box's vicar, John Coren; his right to administer communion; the Book of Common Prayer; and the very basis of established authority in the village. It was an incident unlike anything that had gone before in Box's history. The story is easily told.

Two local residents, Christopher Butler, a weaver, and John Humphreyes, a rough mason (quarryman), organised a protest before morning prayer at St Thomas à Becket and In a tumultor sorte denydd the booke of Comon prayer & the book of the Omiles saying that there could be no edificacion for the people by them and that the unpreaching mynister could not rightly nor had noe power to administer the Sacrement.[5] That afternoon they were joined by Sylvester Butler of Castle Combe and they repeated the attack against the vicar in the churchyard.

|

They wanted a more radical interpretation, perhaps something more like the worship that later Puritans called the Directory of Public Worship. This probably indicates that there was a dissenting minority in Box. The Justices of the Peace reacted strongly against the objectors but the churchwardens at Box pursued a more conciliatory stance. They raised money to install two new bells in the church tower in 1610 and 1617.[6] The tradition of ringing the changes had started with recording the death of the old queen in 1602 and continued for decades thereafter to celebrate her birthday.

Change-ringing was a joyful way of remembering the peaceful traditions of the Elizabethan period. It was a tradition carried on in most areas of England and was unique throughout the continent of Europe. The new bells at Box of the early 1600s are examples of how bell-founding techniques had progressed in the 125 years or so since the mediaeval bells were installed, in particular how the bells may be tuned to a particular pitch while keeping the harmonics under control. How to produce a musical sequence was understood by the end of the 1600s and the first full peal was rung in 1715 at St Peter Mancroft in Norwich. |

Economic Problems

After 1603, religious argument in Box seems to have diminished for several decades and the Speke family, who were reputed to be recusant (Catholic sympathisers), were untroubled by religious debates. Probably people were more concerned about domestic issues. The years 1620 to 1650 were the lowest point of the Little Ice Age. Evidence for this can be seen in the contemporary Cotswold architecture, with steep roofs to shed snow, small windows and large inglenook fireplaces. Annual mean temperatures were 1 to 2 degrees C lower than the present, (which itself is still below the peak of the mediaeval high around 1300). That does not seem very great, but signifies much colder winters during which rivers froze solid and the growing season was drastically shortened. Cotswold stone tiles were made by standing blocks of shelly limestone on end, saturating with water and waiting for ice to do the splitting.

The early 1600s saw chronic local disorder: the plague returned in 1604 and 1627; the cloth trade suffered a severe depression after 1614; there were extremely bad harvests in the 1620s resulting in inflation in grain prices; food protests in 1622; labourers' real wages declined and there were strikes in the west country in 1623.[7]

For those without work, the situation was harsh. Squatters who built on common land were evicted unmercifully. In 1603 the Chippenham Justices of the Peace refused permission for one cottage house within the Comon of Mydlehill built by Anthony Jones and presented to trial Johane (Joanne) Keynes, widow, for living in a small cottage house in Hatt as it did not have two hectares of land attached.[8] The justices were frightened that squatter communities would grow up in Box as they had at Warminster and Broughton Gifford.

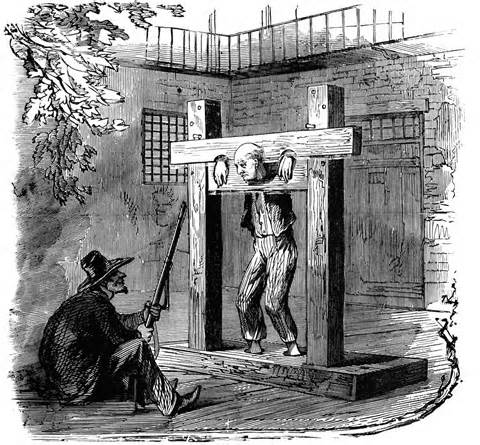

Everywhere there was evidence of the breakdown of rural social order. Squatters and migrants moved to seek work, setting up on wasteland and common or constantly wandering from parish to parish. Poverty and vagrancy were seen as idleness and dishonesty to be punished. Rebellious women (mothers and wives struggling to feed themselves and children) were denounced as witches and punished in the stocks or the ducking stool. All of this disorder was anathema to a Tudor society concerned with status, as expressed in the constant reallocation of seating arrangements in the parish church to allow preference to the gentry.[9]

People regularly complained about their neighbours and were encouraged to do so by collecting fines. Complaints covered all aspects of life, drunkenness, lewdness, mis-behaviour on the Sabbath, violent attacks.[10] Puritan justices warned about disorder arising after church ales and maypole dancing. Complaints were made in Bradford-on-Avon in 1628 against alehouses where: poor workmen and day labourers drown their sorrows whilst their wives and children starved.[11]

Considerable unrest developed because Charles I supported The Book of Sports (recreational activity) which split opinion amongst the clergy and the public.[12] Sundays had become a day of leisure for making merry, wrestling, football and stoolball (cricket). However, these activities often deteriorated into mass participation battles without rules played over huge areas and they resulted in frequent fights, injuries and even fatalities. There were complaints about drunkenness and debauchery; excessive gambling over the results of horse-races and bowling competitions; and thefts or reprisals by losing competitors or even whole villages. For Puritans it was sacrilege on the Lord's Day

The economic situation of many locals deteriorated at this time. Grievances were brought to the attention of the justices but it was beyond local authorities to solve agricultural dips in rural societies. Many got into severe debt and selling everything to Hugh Speke was the only alternative to destitution for some.

Against this background, it was only a matter of time before religious tolerance spilled over into anarchy. The influence of sects, such as Quakers, Anabaptists, ranters and diggers within the New Model Army, was a breeding ground for greater Puritanism. In 1655, during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, the government considered the village insufficiently Puritan and Rev Walter Bushnell, vicar of Box, was removed from office.[13] By then every aspect of belief was under question, including the abolition of bishops, the role and position of altars, predestination, what graven imagery constituted, whether trans-substantiation (creation of the body and blood of Christ in the communion) was real or figurative, whether clergy should wear the surplice; the list of subjects for debate was endless.

Church Court

Whilst theological matters ebbed and flowed, the power of the parish church remained constant in pre- and post-Reformation Box as we can see from the influence of the local Church Court. There were many different legal systems in Box at this time: the royal courts, the manorial court of the lord of the manor and one which concerns us here, the Church Court. Before 1713 the court was held in two rooms above the north aisle of St Thomas à Becket which were called Church Chambers.[14]

Although the concept seems strange to western eyes, it has still continued in Islam with Sharia Law and like it the Church court was one of the most intrusive in Box. For centuries the Catholic Church had jurisdiction over morality, marriage, wills and ecclesiastic matters and surprisingly it continued after the Reformation. The bishop's Protestant apparitor (legal officer) and the archdeacon's official made frequent visitations to Box to discuss ecclesiastic matters with the churchwardens.[15] Box's churchwardens issued bills of presentment (reports) to the bishop, who visited Box every three years; and the archdeacon's official made a visit every 6 months. We know that visitations in Box continued before and after the Reformation, including in 1649.[16]

Based either at the bishop's court at Salisbury or at the archdeacon's court in North Wiltshire, the Church Courts covered many matters that we now call civil. They controlled wills, debt, defamation and marriage licences (for women aged 12 and men aged 14). They covered morality: fornication, drunkenness and weekly church attendance to take the sacraments. They dealt with church matters: building repairs, tithe adjudication and charges against clerics.

After 1603, religious argument in Box seems to have diminished for several decades and the Speke family, who were reputed to be recusant (Catholic sympathisers), were untroubled by religious debates. Probably people were more concerned about domestic issues. The years 1620 to 1650 were the lowest point of the Little Ice Age. Evidence for this can be seen in the contemporary Cotswold architecture, with steep roofs to shed snow, small windows and large inglenook fireplaces. Annual mean temperatures were 1 to 2 degrees C lower than the present, (which itself is still below the peak of the mediaeval high around 1300). That does not seem very great, but signifies much colder winters during which rivers froze solid and the growing season was drastically shortened. Cotswold stone tiles were made by standing blocks of shelly limestone on end, saturating with water and waiting for ice to do the splitting.

The early 1600s saw chronic local disorder: the plague returned in 1604 and 1627; the cloth trade suffered a severe depression after 1614; there were extremely bad harvests in the 1620s resulting in inflation in grain prices; food protests in 1622; labourers' real wages declined and there were strikes in the west country in 1623.[7]

For those without work, the situation was harsh. Squatters who built on common land were evicted unmercifully. In 1603 the Chippenham Justices of the Peace refused permission for one cottage house within the Comon of Mydlehill built by Anthony Jones and presented to trial Johane (Joanne) Keynes, widow, for living in a small cottage house in Hatt as it did not have two hectares of land attached.[8] The justices were frightened that squatter communities would grow up in Box as they had at Warminster and Broughton Gifford.

Everywhere there was evidence of the breakdown of rural social order. Squatters and migrants moved to seek work, setting up on wasteland and common or constantly wandering from parish to parish. Poverty and vagrancy were seen as idleness and dishonesty to be punished. Rebellious women (mothers and wives struggling to feed themselves and children) were denounced as witches and punished in the stocks or the ducking stool. All of this disorder was anathema to a Tudor society concerned with status, as expressed in the constant reallocation of seating arrangements in the parish church to allow preference to the gentry.[9]

People regularly complained about their neighbours and were encouraged to do so by collecting fines. Complaints covered all aspects of life, drunkenness, lewdness, mis-behaviour on the Sabbath, violent attacks.[10] Puritan justices warned about disorder arising after church ales and maypole dancing. Complaints were made in Bradford-on-Avon in 1628 against alehouses where: poor workmen and day labourers drown their sorrows whilst their wives and children starved.[11]

Considerable unrest developed because Charles I supported The Book of Sports (recreational activity) which split opinion amongst the clergy and the public.[12] Sundays had become a day of leisure for making merry, wrestling, football and stoolball (cricket). However, these activities often deteriorated into mass participation battles without rules played over huge areas and they resulted in frequent fights, injuries and even fatalities. There were complaints about drunkenness and debauchery; excessive gambling over the results of horse-races and bowling competitions; and thefts or reprisals by losing competitors or even whole villages. For Puritans it was sacrilege on the Lord's Day

The economic situation of many locals deteriorated at this time. Grievances were brought to the attention of the justices but it was beyond local authorities to solve agricultural dips in rural societies. Many got into severe debt and selling everything to Hugh Speke was the only alternative to destitution for some.

Against this background, it was only a matter of time before religious tolerance spilled over into anarchy. The influence of sects, such as Quakers, Anabaptists, ranters and diggers within the New Model Army, was a breeding ground for greater Puritanism. In 1655, during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, the government considered the village insufficiently Puritan and Rev Walter Bushnell, vicar of Box, was removed from office.[13] By then every aspect of belief was under question, including the abolition of bishops, the role and position of altars, predestination, what graven imagery constituted, whether trans-substantiation (creation of the body and blood of Christ in the communion) was real or figurative, whether clergy should wear the surplice; the list of subjects for debate was endless.

Church Court

Whilst theological matters ebbed and flowed, the power of the parish church remained constant in pre- and post-Reformation Box as we can see from the influence of the local Church Court. There were many different legal systems in Box at this time: the royal courts, the manorial court of the lord of the manor and one which concerns us here, the Church Court. Before 1713 the court was held in two rooms above the north aisle of St Thomas à Becket which were called Church Chambers.[14]

Although the concept seems strange to western eyes, it has still continued in Islam with Sharia Law and like it the Church court was one of the most intrusive in Box. For centuries the Catholic Church had jurisdiction over morality, marriage, wills and ecclesiastic matters and surprisingly it continued after the Reformation. The bishop's Protestant apparitor (legal officer) and the archdeacon's official made frequent visitations to Box to discuss ecclesiastic matters with the churchwardens.[15] Box's churchwardens issued bills of presentment (reports) to the bishop, who visited Box every three years; and the archdeacon's official made a visit every 6 months. We know that visitations in Box continued before and after the Reformation, including in 1649.[16]

Based either at the bishop's court at Salisbury or at the archdeacon's court in North Wiltshire, the Church Courts covered many matters that we now call civil. They controlled wills, debt, defamation and marriage licences (for women aged 12 and men aged 14). They covered morality: fornication, drunkenness and weekly church attendance to take the sacraments. They dealt with church matters: building repairs, tithe adjudication and charges against clerics.

|

The purpose of the court was to enforce morality and the receipt of communion. They controlled personal behaviour to bring order, bland uniformity and the maintenance of the status quo characterised by the report omnia bene (all is well).

The sanctions they used were the opprobrium of neighbours (public denunciation in the parish church), humiliation (whipping pre-Reformation and the stocks in the Market Place afterwards) and, if all else failed, excommunication (sometimes similar to outlawry). We can suppose that Box residents resented the church court for the cost of its legal charges and the intrusion into the affairs of neighbours that it encouraged. The courts were seen as unfair for many reasons, partly because of their strong moral attitude towards the deficiencies of the laity in contrast to their lax treatment of clerics. |

Whilst the Church Courts exercised conformity amongst the lay population, they significantly failed to improve the standards of the local clergy in the village in the years both before and after the Reformation. An official visit by the bishop in 1553 recorded that there were no sermons or preaching by the minister in Box.[17] The poor standards of the clergy had lasted a long time throughout England. In 1561 only 25 of 220 clerics were found to be learned in Latin; 15 unlearned (in writing) and 8 totally unlearned (reading and writing).[18]

Witches

The peak of witch trials also coincided with the low point of the Little Ice Age and on a European scale also coincided with the rye-bread belt of eastern Germany and indeed anywhere that rye-bread was made. Stored under cold and damp conditions, rye flour grows a mould known as ergot. Ergot spores are now known to be cumulatively poisonous and hallucinogenic - hence the reports of flying on broomsticks and so on.

Tithe System

In Box the tithe system (payment of one-tenth of farm produce to the church) had remained constant for hundreds of years.

We have records in Box of the terriers (surveys) made by the church authorities from 1672 until 1790.[19]

They were split into the Great Tithe on corn and the Lesser Tithes on livestock, fruit and other crops. In the early 1600s the lesser tithes included: wool, lambs, cow white (milk), coppices, wood, groves... underwood and hedgerow which is sold.[20] At Ditteridge they included honey, yermoth (the second crop of grass) and fitches (vetches or legumes).[21] Of course, they were not paid to the vicar (the stipendiary cleric) but to the rector (sometimes called the Improprietor) who was at Monkton Farley Priory before the Reformation and a layman who held the advowsen (right to nominate the vicar) in Protestant Box.

We can see how all-encompassing the tithe system was in Box from the detail recorded in 1704; see Appendix.[22]

Witches

The peak of witch trials also coincided with the low point of the Little Ice Age and on a European scale also coincided with the rye-bread belt of eastern Germany and indeed anywhere that rye-bread was made. Stored under cold and damp conditions, rye flour grows a mould known as ergot. Ergot spores are now known to be cumulatively poisonous and hallucinogenic - hence the reports of flying on broomsticks and so on.

Tithe System

In Box the tithe system (payment of one-tenth of farm produce to the church) had remained constant for hundreds of years.

We have records in Box of the terriers (surveys) made by the church authorities from 1672 until 1790.[19]

They were split into the Great Tithe on corn and the Lesser Tithes on livestock, fruit and other crops. In the early 1600s the lesser tithes included: wool, lambs, cow white (milk), coppices, wood, groves... underwood and hedgerow which is sold.[20] At Ditteridge they included honey, yermoth (the second crop of grass) and fitches (vetches or legumes).[21] Of course, they were not paid to the vicar (the stipendiary cleric) but to the rector (sometimes called the Improprietor) who was at Monkton Farley Priory before the Reformation and a layman who held the advowsen (right to nominate the vicar) in Protestant Box.

We can see how all-encompassing the tithe system was in Box from the detail recorded in 1704; see Appendix.[22]

Appendix

Box's Tithe Dues

Terrier of all the Housing, Glebelands, Commons, Tithes, Offerings, & the other Customary Dues belonging to the Vicarage of BOX in the Diocese of SARUM, being called for, & accordingly delivered in under the hand of the Minister & Churchwardens & Chief Inhabitants of the said Parish, December 23rd 1704

The Vicarage House, with the outlets, gardens, & orchard thereunto belonging. The use of two rooms, called the Church Chambers; over the north isle of the Church. A house at the south-east side of the Church, containing two bays of building.

Two stables containing two bays of building.

The Churchyard (the gates & bounds whereof, are to be upheld & maintained by the Parish.) a right of Common in all the Commons belonging to the said Parish.

The tenth cock (stook) of all hay growing in the said Parish & of French-grass, called St Jane, or of the seed of it.

For the milk of every cow fed within the said Parish three pence to be paid at Lammas-tide (the loaf mass held on 1 August).

For all the calves fallen in the said Parish, nine pence to be paid at Lammas-tide. If sold, the tenth of the money. If killed by the owner, one shoulder. For every calf weaned, one half penny: But if sold before they come to be milked or yoked, the tenth of the price.

Of the wool of all sheep kept within the said Parish, the tenth weight, or the tenth pound; & the tenth of the Locks. If the sheep be sold before shear-time, for each sheep a farthing for every month they have been kept within the said Parish: & so for the agistment (grazing) of all sheep.

The tenth, or (if no more) the seventh, of all lambs; to be paid on St. Mark's-day (25 April).

For unprofitable cattle, the tenth penny-rent of their feeding.

The tenth, or (if no more) the seventh of all pigs.

For every hen an egg; for the cock two to be paid at Easter.

The Tithe of apples, pears, & all other fruit.

The tenth acre, or tenth perch of all Coppice-wood. Of all hedge-rows the are sold the tenth- of the money: And the tenth of all Hedge-rows reserved be the owner for the own use, if they be above a perch broad.

The Easter Offering of every Communicant two pence: & for every garden a penny.

For the mill called Pinchin's Mill, five shillings to be paid at Lady-day (25 March) .

For Parker's (alias Crook's Mill), five shillings to be paid at Lady-day.

For Bollen's Mill, one shilling four pence; to be paid at Lady-day.

By a certain Composition between the monks of Farley (anciently Impropriators) & the Vicar of Box, it was agreed that out of the Parsonage or Impropriation of Box aforesaid, there were yearly to be paid to the said Vicar, five quarters of wheat, five quarters of Barley, two quarters of Oates, & three quarters of Dredge or Misceline (Mixture such as of barley & oats) For the which said last three quarters, (because there is now no Misceline sowed in the said Parish) the same is paid in twelve bushels of barley, & twelve bushels of oats more: being in all fifteen quarters of corn: which are to be paid yearly to the Vicar by the Impropriator, or so much money as the said several sorts of grain do yield in the neighbouring markets, as the Impropriator and vicar can agree.

Conclusion

Whilst we no longer regard many of these issues as relevant to the modern church, we can see how intrusive religion was into people's daily lives. That is part of the reason why it was so important in Tudor and Stuart Box.

Box's Tithe Dues

Terrier of all the Housing, Glebelands, Commons, Tithes, Offerings, & the other Customary Dues belonging to the Vicarage of BOX in the Diocese of SARUM, being called for, & accordingly delivered in under the hand of the Minister & Churchwardens & Chief Inhabitants of the said Parish, December 23rd 1704

The Vicarage House, with the outlets, gardens, & orchard thereunto belonging. The use of two rooms, called the Church Chambers; over the north isle of the Church. A house at the south-east side of the Church, containing two bays of building.

Two stables containing two bays of building.

The Churchyard (the gates & bounds whereof, are to be upheld & maintained by the Parish.) a right of Common in all the Commons belonging to the said Parish.

The tenth cock (stook) of all hay growing in the said Parish & of French-grass, called St Jane, or of the seed of it.

For the milk of every cow fed within the said Parish three pence to be paid at Lammas-tide (the loaf mass held on 1 August).

For all the calves fallen in the said Parish, nine pence to be paid at Lammas-tide. If sold, the tenth of the money. If killed by the owner, one shoulder. For every calf weaned, one half penny: But if sold before they come to be milked or yoked, the tenth of the price.

Of the wool of all sheep kept within the said Parish, the tenth weight, or the tenth pound; & the tenth of the Locks. If the sheep be sold before shear-time, for each sheep a farthing for every month they have been kept within the said Parish: & so for the agistment (grazing) of all sheep.

The tenth, or (if no more) the seventh, of all lambs; to be paid on St. Mark's-day (25 April).

For unprofitable cattle, the tenth penny-rent of their feeding.

The tenth, or (if no more) the seventh of all pigs.

For every hen an egg; for the cock two to be paid at Easter.

The Tithe of apples, pears, & all other fruit.

The tenth acre, or tenth perch of all Coppice-wood. Of all hedge-rows the are sold the tenth- of the money: And the tenth of all Hedge-rows reserved be the owner for the own use, if they be above a perch broad.

The Easter Offering of every Communicant two pence: & for every garden a penny.

For the mill called Pinchin's Mill, five shillings to be paid at Lady-day (25 March) .

For Parker's (alias Crook's Mill), five shillings to be paid at Lady-day.

For Bollen's Mill, one shilling four pence; to be paid at Lady-day.

By a certain Composition between the monks of Farley (anciently Impropriators) & the Vicar of Box, it was agreed that out of the Parsonage or Impropriation of Box aforesaid, there were yearly to be paid to the said Vicar, five quarters of wheat, five quarters of Barley, two quarters of Oates, & three quarters of Dredge or Misceline (Mixture such as of barley & oats) For the which said last three quarters, (because there is now no Misceline sowed in the said Parish) the same is paid in twelve bushels of barley, & twelve bushels of oats more: being in all fifteen quarters of corn: which are to be paid yearly to the Vicar by the Impropriator, or so much money as the said several sorts of grain do yield in the neighbouring markets, as the Impropriator and vicar can agree.

Conclusion

Whilst we no longer regard many of these issues as relevant to the modern church, we can see how intrusive religion was into people's daily lives. That is part of the reason why it was so important in Tudor and Stuart Box.

References

[1] See articles on Reformation and Civil War

[2] Conrad Russell, The Causes of the English Civil War, 1990, Clarendon Press, p.84 asserts that the word Anglican was unknown before 1635.

[3] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol III, p.39

[4] Conrad Russell, The Causes of the English Civil War, p.70

[5] BH Cunniston, Records of the County of Wilts, 1932, Devizes, p.5

[6] See St Thomas à Becket article

[7] Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England 1570-1640, 1987, Cambridge University Press, p.78

[8] BH Cunniston, Records of the County of Wilts, p.5

[9] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, 1987, Oxford University Press, p.32

[10] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.47-50, 64

[11] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.84

[12] History Extra podcast, 12 July 2012

[13] See Walter Bushnell article

[14] See St Thomas à Becket article

[15] Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England 1570-1640, p.1-57

[16] See Walter Bushnell article

[17] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol III, p.30

[18] Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England 1570-1640, p.86

[19] Records held by Mike Lyons

[20] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 56, p.42

[21] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 56, p.144

[22] Courtesy Mike Lyons

[1] See articles on Reformation and Civil War

[2] Conrad Russell, The Causes of the English Civil War, 1990, Clarendon Press, p.84 asserts that the word Anglican was unknown before 1635.

[3] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol III, p.39

[4] Conrad Russell, The Causes of the English Civil War, p.70

[5] BH Cunniston, Records of the County of Wilts, 1932, Devizes, p.5

[6] See St Thomas à Becket article

[7] Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England 1570-1640, 1987, Cambridge University Press, p.78

[8] BH Cunniston, Records of the County of Wilts, p.5

[9] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, 1987, Oxford University Press, p.32

[10] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.47-50, 64

[11] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.84

[12] History Extra podcast, 12 July 2012

[13] See Walter Bushnell article

[14] See St Thomas à Becket article

[15] Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England 1570-1640, p.1-57

[16] See Walter Bushnell article

[17] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol III, p.30

[18] Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England 1570-1640, p.86

[19] Records held by Mike Lyons

[20] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 56, p.42

[21] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 56, p.144

[22] Courtesy Mike Lyons