|

Civil Wars 1642-51 and After

Alan Payne, October 2016 The English Civil Wars were enormously costly in terms of human lives. It was a devastating event that affected all Englishmen and whose consequences lasted several decades. In total 86,000 were killed in combat and 129,000 civilians died through war-related causes.[1] A larger proportion of the population (3.6%) were killed in England than in any war since. This compares to 1.6% in World War 1 and 0.6% in World War 2. Right: Battle of Naseby, unnown artist, 1645 (courtesy wikipaedia) |

There were several different skirmishes in the war; the First English Civil War lasted from 1642 to 1646, the Second from 1648 to 1649, the Third 1649 to 1651; and, of course, this was accompanied by the execution of King Charles I in 1649. This article deals with the impact of the war on the people of Box.

Battles Around Box

For long periods the war was on the very edge of Box's parish boundaries. The remnants of both armies passed through Box, rushing to and from the battles, seeking local overnight billets or simply defending their homes. For long periods Box was in the frontier region with control varying between the two armies.[2] The western counties were a vital source of supplies for the armies who required food, arms and uniforms and the area also controlled vital routes and access to the port of Bristol.[3]

We might imagine that the old medieval road through Kingsdown saw frequent troop movement as men walked past the Old Jockey and through Kingsdown to get from Bath to Roundway. A musket ball has been found locally which may indicate some action in the area.[4] It is alleged that Cromwell's troops were billeted in the village during the 1640s but there is no known evidence for this.[5] The contemporary writer, John Aubrey, seems to confirm this, however, when he said: There is a tradition that (Cheney) Court, which is large and surrounded by a high wall, was used for some military purpose in the Civil Wars.[6] By popular legend, during her escape to France in July 1644, Queen Henrietta Maria, Catholic wife of Charles I, hid in Cheney Court to avoid Cromwell's troops.[7]

Control of the area around Box ebbed and flowed.[8] By November 1642, Somerset and Wiltshire were largely under the control of the Parliamentarians, but the king retook local towns that year at Marlborough, Malmesbury, Devizes, Salisbury and Cirencester. Box then became trapped between fierce and bloody battles on its borders. On 2 July 1643 the Royalists seized the bridge at Bradford-on-Avon and a day later skirmishes took place at Claverton and other positions south and east of Bath. The main Royalist force moved north through Batheaston to Marshfield, probably going through parts of Box, until the armies eventually met in two open-field battles at Lansdown and Roundway Down in July 1643

For long periods the war was on the very edge of Box's parish boundaries. The remnants of both armies passed through Box, rushing to and from the battles, seeking local overnight billets or simply defending their homes. For long periods Box was in the frontier region with control varying between the two armies.[2] The western counties were a vital source of supplies for the armies who required food, arms and uniforms and the area also controlled vital routes and access to the port of Bristol.[3]

We might imagine that the old medieval road through Kingsdown saw frequent troop movement as men walked past the Old Jockey and through Kingsdown to get from Bath to Roundway. A musket ball has been found locally which may indicate some action in the area.[4] It is alleged that Cromwell's troops were billeted in the village during the 1640s but there is no known evidence for this.[5] The contemporary writer, John Aubrey, seems to confirm this, however, when he said: There is a tradition that (Cheney) Court, which is large and surrounded by a high wall, was used for some military purpose in the Civil Wars.[6] By popular legend, during her escape to France in July 1644, Queen Henrietta Maria, Catholic wife of Charles I, hid in Cheney Court to avoid Cromwell's troops.[7]

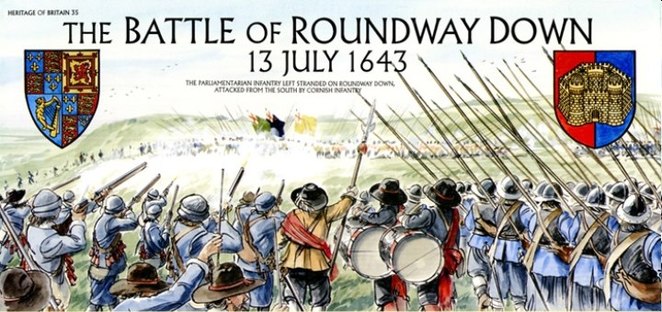

Control of the area around Box ebbed and flowed.[8] By November 1642, Somerset and Wiltshire were largely under the control of the Parliamentarians, but the king retook local towns that year at Marlborough, Malmesbury, Devizes, Salisbury and Cirencester. Box then became trapped between fierce and bloody battles on its borders. On 2 July 1643 the Royalists seized the bridge at Bradford-on-Avon and a day later skirmishes took place at Claverton and other positions south and east of Bath. The main Royalist force moved north through Batheaston to Marshfield, probably going through parts of Box, until the armies eventually met in two open-field battles at Lansdown and Roundway Down in July 1643

|

The first was a fairly indecisive battle at Lansdown, Bath, on 5 July when the Royalist forces were badly out-manoeuvred. The second was a cavalry battle on 13 July 1643 at Roundway Down, Devizes, one of the key battles in the English Civil War. The Royalists totally routed the Parliamentarians as they fled across the Down, many plunging to their deaths down the steep gullies of Oliver's Castle. This success enabled the Royalist leaders Hopton and Prince Rupert to capture both Bath and Bristol.

|

From the summer of 1644, control of the area varied. Large armies from both sides used the routes through Wiltshire and Somerset to access areas further west down to Cornwall. Chippenham, Devizes and Salisbury endured bitter hand-to-hand fighting in December 1644. The creation of a more professional army (the New Model Army) in June 1645 under Sir Thomas Fairfax ensured that the area remained solidly parliamentarian thereafter.

Allegiances in Box

The war split families and friends. Most families would have been affected and it is estimated that a quarter of the adult male population actually fought at some time.[9] We believe that allegiance was split by status or class.[10] People were forced to choose sides regardless of their personal beliefs or indifference partly based on social or religious factors.[11] Sometimes members of the same family found themselves fighting in opposition. When Sir William Waller commanded the Parliamentary forces at the Battle of Lansdown in 1643, he came face-to-face on the battlefield with his lifelong friend, Sir Ralph Hopton, who led the Royalist army.

In Box the established authority (including the gentry and the vicar) probably supported the Royalists but the aspiring classes (clothiers, yeomen, husbandmen and quarry workers) were Puritan by inclination or wanted the sort of change advocated by the Parliamentarians.

The war split families and friends. Most families would have been affected and it is estimated that a quarter of the adult male population actually fought at some time.[9] We believe that allegiance was split by status or class.[10] People were forced to choose sides regardless of their personal beliefs or indifference partly based on social or religious factors.[11] Sometimes members of the same family found themselves fighting in opposition. When Sir William Waller commanded the Parliamentary forces at the Battle of Lansdown in 1643, he came face-to-face on the battlefield with his lifelong friend, Sir Ralph Hopton, who led the Royalist army.

In Box the established authority (including the gentry and the vicar) probably supported the Royalists but the aspiring classes (clothiers, yeomen, husbandmen and quarry workers) were Puritan by inclination or wanted the sort of change advocated by the Parliamentarians.

|

We can suppose that many ordinary Box people were Parliamentarian, as in other Wiltshire clothing and dairying areas.[12] In August 1642 husbandmen and clothiers defeated the Cavalier forces armed with: pitchforks, dungpicks and suchlike weapon before praying and singing Puritan psalms.[13] Local people were subjected to massive propaganda of pamphlets, sermons and declarations; and located between the Parliamentary garrisons at Malmesbury and Great Chalfield they probably have had little option but to support the strongest side.[14]

Effects of the War The war brought considerable economic problems: local parish taxation, excise tax (on domestic goods), the quartering and provisioning of soldiers, and the plundering and despoiling of the countryside. War taxation was introduced through weekly contributions, including the Parliamentarian levy on Box of £8.15s.0d after 1642.[15] By January 1645 the money raised in Box was down to £5.9s.4d and in the following months the total amount was recorded as Returned (in other words no money).[16] The records of the parliamentary garrison at Malmesbury show the extent of provisioning taken from the village: From Box Six bushels of wheat and Goods brought into the garrison from Hazelbury.[17] Quartering of troops was severe in 1644 and by the close of warfare the compulsory conscription of local people into the militia started.[18] |

One of the main concerns in the war was the defence of the local community against a breakdown in law and order. In October 1643 the Wiltshire Quarter Sessions were abandoned because the county was in a dangerous state owing to the souldiers.[19] The rising of the Clubmen (local militia defenders) in the West in 1644 was a massive popular movement against destruction and violence.[20] The Clubmen reflected the economic concerns of local residents with massive rent arrears; rising disorder caused by army desertion and unemployed vagrants; and the absence of local authority after the resignation of Wiltshire's Commissioners.[21]

|

Box in the Commonwealth, 1646 - 1660

The war caused severe local problems during the government of Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth (Republic) that followed the Parliamentary victory.[22] There were various local difficulties: Chippenham weavers complained about unemployment in 1647; poor harvests were experienced in 1647 and 1648; and later food riots, complaints about enclosure and riots against excisemen (tax collectors) in Warminster, Melksham, Bristol and Chippenham.[23] For those who had been disabled in the Civil War farming was no longer possible and many turned to weaving to eke out a living. Two weavers were needed for each loom and a husband and wife team was a common arrangement.[24] The weakness of local government threatened to compromise social order. There were many social problems and a recurrence of the religious divisions that had simmered in the village since 1603. As well as a struggle for military control, the Civil War was a confrontation about the form that the established church should take: traditionalists wanted to return to a high altar, radicals sought to abolish the entire Church hierarchy.[25] |

Evidence of the complex religious background is seen in the celebrated case of Walter Bushnell, vicar of Box.[26] It is one of the fullest descriptions we have of the confused religious situation in the country during the Protectorate.[27] Bushnell was the nomination of George Speke. He became vicar of Box in 1644 and served for the next 12 years, when he was removed from office by the Commissioners in 1656 for being an ignorant and scandalous minister. Bushnell published his version of events and was re-instated, together with the parish clerk Henry Arlet, on the restoration of Charles II in 1660. Bushnell continued until his death in 1667 and Arlet served until 1694.[28]

The Bushnell trial was not unique. The Commissioners of the Committee of Ejectors investigated many parish priests during the period 1645 to 1660. Some priests were accused of involvement with the King’s army. Some were prosecuted for using the Common Prayer Book after 1645. Others were accused of theological variations, including putting up pictures of the Ascension, or the elevation of the communion table.[29] In Wiltshire parishes, eighty clergy were thrown out of their livings for being too traditional or having potential Royalist sympathies; sixty clergy left in the 1660’s because they were too radical to accept the authority of bishops, the Book of Common Prayer and the Established Church.[30]

The Bushnell trial was not unique. The Commissioners of the Committee of Ejectors investigated many parish priests during the period 1645 to 1660. Some priests were accused of involvement with the King’s army. Some were prosecuted for using the Common Prayer Book after 1645. Others were accused of theological variations, including putting up pictures of the Ascension, or the elevation of the communion table.[29] In Wiltshire parishes, eighty clergy were thrown out of their livings for being too traditional or having potential Royalist sympathies; sixty clergy left in the 1660’s because they were too radical to accept the authority of bishops, the Book of Common Prayer and the Established Church.[30]

The Civil War shocked people so fundamentally that they were desperate to move on and forget about it when peace came.

John Aubrey was a contemporary but he does not mention the war in his writings. It was similar to the reactions after the First and Second World Wars. The problems it threw up took generations to resolve, including the roles of the king and parliament, pluralism in religion, settlement of Scottish and Irish independence, the rise of the dissenting religious movements, and the ways of raising taxation in England. Some of these issues were not fully resolved until Victorian times and greatly affected society in Box and throughout the country.

John Aubrey was a contemporary but he does not mention the war in his writings. It was similar to the reactions after the First and Second World Wars. The problems it threw up took generations to resolve, including the roles of the king and parliament, pluralism in religion, settlement of Scottish and Irish independence, the rise of the dissenting religious movements, and the ways of raising taxation in England. Some of these issues were not fully resolved until Victorian times and greatly affected society in Box and throughout the country.

References

[1] Robert Tombs, the English and their History, 2014, Allen Lane, p.242

[2] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, 1987, Oxford University Press, p.146-8

[3] Dr John Wroughton, The Civil War in the West, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/west_01.shtml

[4] In the garden of Old Jockey Farm

[5] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, 1987, p.6

[6] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, p.59

[7] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, p.7 reverse

[8] Dr John Wroughton, The Civil War in the West

[9] Dr John Wroughton, The Civil War in the West

[10] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.168

[11] Conrad Russell, The Causes of the English Civil War, 1990, Clarendon Press, p.59

[12] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.165

[13] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.166

[14] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.164

[15] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 2, p.65

[16] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 2, p.90-1

[17] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 2, p.65

[18] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.151, 184

[19] BH Cunniston, Records of County of Wiltshire, 1932

[20] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.156-9

[21] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.158-61

[22] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.229

[23] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.213

[24] J De L Mann, The Cloth Industry in the West of England, 1987, Alan Sutton, p. 89

[25] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.104

[26] See Rise and Fall of Walter Bushnell

[27] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p199-202

[28] Parish Magazine, April 1935

[29] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol III, p.41

[30] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, p.105-6

[1] Robert Tombs, the English and their History, 2014, Allen Lane, p.242

[2] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, 1987, Oxford University Press, p.146-8

[3] Dr John Wroughton, The Civil War in the West, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/west_01.shtml

[4] In the garden of Old Jockey Farm

[5] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, 1987, p.6

[6] John Aubrey, Wiltshire Topographical Collections, 1862, Longman, p.59

[7] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, p.7 reverse

[8] Dr John Wroughton, The Civil War in the West

[9] Dr John Wroughton, The Civil War in the West

[10] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.168

[11] Conrad Russell, The Causes of the English Civil War, 1990, Clarendon Press, p.59

[12] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.165

[13] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.166

[14] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.164

[15] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 2, p.65

[16] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 2, p.90-1

[17] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 2, p.65

[18] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.151, 184

[19] BH Cunniston, Records of County of Wiltshire, 1932

[20] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.156-9

[21] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.158-61

[22] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.229

[23] David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion, p.213

[24] J De L Mann, The Cloth Industry in the West of England, 1987, Alan Sutton, p. 89

[25] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.104

[26] See Rise and Fall of Walter Bushnell

[27] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p199-202

[28] Parish Magazine, April 1935

[29] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol III, p.41

[30] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, p.105-6