|

Rebuilding the Village, 1708 - 29:

Church, Charity School and Poorhouse Alan Payne, January 2019 The years 1708 to 1729 saw possibly the most concentrated rebuilding of the centre of the village in the area around Box Church. The work in those twenty years was typically Georgian, although at the very commencement of the period; the inspiration came from two local individuals: the vicar, Rev George Miller (sometimes called Millard), and Dame Rachel Speke, the last of the Speke dynasty. This is not an attempt to rewrite the excellent articles already on the website about the Rev George Miller and Box's Charity School, but to understand how and why it all happened. Background The work in Box village shows just how much English society was moving at that time. George Louis, the Elector (ruler) of Hanover, Germany, had become the heir to the English throne by the Act of Settlement 1701 which bypassed about fifty closer candidates because they were Catholic even though he was only Queen Ann's second cousin. On a national level, this Act showed the power of Britain's Protestant country gentlemen in Parliament. On a local level, the changes were a precedent reflected in the expansion of local authority by the English gentry with an emphasis on self-determination, fear of foreigners and outsiders, and the belief that Elizabeth I's religious settlement should be the only one. |

Some of these changes came from the writing of John Locke. Locke had published his Essay Concerning Human Understanding in 1690, presenting his views that knowledge was determined by experience and that all humans can improve through conscious effort. His writing is generally believed to have led to the ideas of the Enlightenment, the concept of a social contract between the authority of the state and individual people. Against this background of change, the leaders in Box's society wanted to improve the position of certain disadvantaged residents.

|

It s sometimes claimed that the Georgian period was an Age of Reason, and not particularly religious: The churches in England, such as they were, lacked vitality... there was little enthusiasm for spiritual matters.[1] But the truth seems to be more complex, depending on where you look for evidence.

It was a time when a new form of the church was evolving. John Wesley emphasised that every individual had merit in their own right such as in his 1722 sermon on The Parable of the Talents.[2] Against the challenge of the dissenting claims to put the Bible under every weaver and chambermaid's arm, the SPCK (Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge), founded in 1698, encouraged endowments to create elementary schools in Church of England parishes.[3] Charity children were to be instructed in piety, virtue and honesty, to be dutiful and obedient, and to accept their humble place in the social order.[4] Left: John Locke painted by Godfrey Kneller, St Petersburg State Hermitage Museum (courtesy Wikipedia) |

The Main Players

The Rev George Miller (sometimes calling himself Millard) was at the centre of all the changes in Box. He was a person who owed his position to patronage, as was common at the time. George was presented (installed) in the rectory of Calstone, Calne in 1701 by lord of the manor William Duckett, appointed curate in Box in the same year by George Petty Speke, and became vicar in St Thomas à Becket Church on the 17 September 1707 until his death in July 1740, courtesy of the Northey family.[5]

From his correspondence we get a personal view of him, a determined man committed to making a difference.[6] His writings may seem ingratiating to us because of the flowery language: I begg my most humble duty and service to the honourable society (SPCK), upon whose labours I shall for ever pray for the Divine-Blessing.[7] But we should not judge from our perspective of abbreviated Instagram posts - try reading Alexander Pope's 1712 The Rape of the Locke to understand contemporary language if you have enough time to spare.

This was a time of great change in English society including agricultural improvement that reduced the need for labourers, the flight of people from rural areas into towns and the beginning of a process that we have called the Industrial Revolution. Change was also evident in Box. The bloodline of the Speke family, lords of Box Manor, had died out and the dowager, Dame Rachel Speke, had only a life interest in the estate. She lived at Hazelbury Manor with her second husband Richard Musgrave.[8] When she died without heir in 1726, her nephew George Petty Speke and his son, Thomas Speke, inherited some property but most of the assets were sold to William Northey.[9] However, the Speke family was able to make donations to Rev Miller's projects out of the proceeds of those sales.

Charity School, started in 1708

The first project devised by Rev Miller was a charity school in 1708.[10] As well as being an entirely laudable project, there was also a financial benefit in that uneducated orphan children would no longer be a burden on the parish rates if they could find employment.[11] With moral instruction through the Catechism (religious questions and answers), they might even become upstanding citizens. George extended the work by incentivising older children (as think themselves too bigg to goe to school) to become literate and to teach the younger ones. In return for this, they received payment of 5 shillings for each charity child who could sight-read a chapter in the Bible. It recompensed the older children for the loss of wages as labourers or farm workers.

The charity school expanded as sufficient income was received. Several gifts were £100, which is perhaps equivalent to about £25,000 in today's terms. These were very substantial gifts for a nascent school in an isolated rural village. First, from 1708 to 1712, teaching was held in the church itself at little cost; from 1712 to 1722 in an unidentified building with a very spacious chamber, belonging to the parish .. under which are two large rooms, possibly an extension to the church.[12] From 1722 to 1729 the school was in a new seven-room house at Springfield used to house the schoolmaster and a schoolroom; after 1729, the two top floors of the Poorhouse were used.[13] The raising of these enormous sums of money over a twenty year period reflects George Miller's powers of persuasion, his contacts and his persistence.

Box Church Restored 1713

In the middle of the school project, George launched a major rebuilding of Box Church in 1713.[14] The north aisle was substantially rebuilt and a large buttress added: windows were installed on both sides of the north door; the east end of the north aisle was made to incorporate the Hazelbury chapel with its 14th century window; and the west end of the north aisle improved. George later said that the aisle holds more than 100 (people).[15] In the chancel, the south and east walls were replaced with a 14th century window (now with Victorian stained glass and called the Pinchin Memorial window) being retained in the east wall.

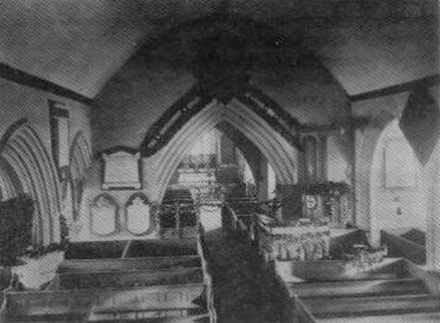

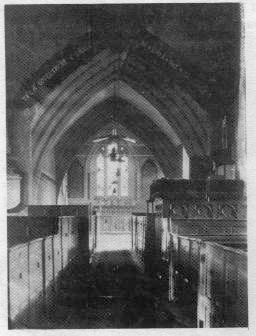

The work may also have involved internal alterations. Two first floor rooms were removed believed to have been the old Church Chambers where the ecclesiastic court would have met at regular intervals to adjudicate wills, marriages and the work of the churchwardens. It is probable that the old pews were recovered, in red or green baize, studded with brass nails and with a candle bracket at each end. The high pews were let to important families in the village on leasehold or copyhold terms, almost as if they were owned.[16] They enabled some members of the congregation to make an entrance, be dutiful in the privacy of their pew for a short time, then exit without attending the whole service. In later years Box Church was described as crowded with hideous pews and with more hideous galleries carried up nearly to the roof with access to one through a window.[17]

The Rev George Miller (sometimes calling himself Millard) was at the centre of all the changes in Box. He was a person who owed his position to patronage, as was common at the time. George was presented (installed) in the rectory of Calstone, Calne in 1701 by lord of the manor William Duckett, appointed curate in Box in the same year by George Petty Speke, and became vicar in St Thomas à Becket Church on the 17 September 1707 until his death in July 1740, courtesy of the Northey family.[5]

From his correspondence we get a personal view of him, a determined man committed to making a difference.[6] His writings may seem ingratiating to us because of the flowery language: I begg my most humble duty and service to the honourable society (SPCK), upon whose labours I shall for ever pray for the Divine-Blessing.[7] But we should not judge from our perspective of abbreviated Instagram posts - try reading Alexander Pope's 1712 The Rape of the Locke to understand contemporary language if you have enough time to spare.

This was a time of great change in English society including agricultural improvement that reduced the need for labourers, the flight of people from rural areas into towns and the beginning of a process that we have called the Industrial Revolution. Change was also evident in Box. The bloodline of the Speke family, lords of Box Manor, had died out and the dowager, Dame Rachel Speke, had only a life interest in the estate. She lived at Hazelbury Manor with her second husband Richard Musgrave.[8] When she died without heir in 1726, her nephew George Petty Speke and his son, Thomas Speke, inherited some property but most of the assets were sold to William Northey.[9] However, the Speke family was able to make donations to Rev Miller's projects out of the proceeds of those sales.

Charity School, started in 1708

The first project devised by Rev Miller was a charity school in 1708.[10] As well as being an entirely laudable project, there was also a financial benefit in that uneducated orphan children would no longer be a burden on the parish rates if they could find employment.[11] With moral instruction through the Catechism (religious questions and answers), they might even become upstanding citizens. George extended the work by incentivising older children (as think themselves too bigg to goe to school) to become literate and to teach the younger ones. In return for this, they received payment of 5 shillings for each charity child who could sight-read a chapter in the Bible. It recompensed the older children for the loss of wages as labourers or farm workers.

The charity school expanded as sufficient income was received. Several gifts were £100, which is perhaps equivalent to about £25,000 in today's terms. These were very substantial gifts for a nascent school in an isolated rural village. First, from 1708 to 1712, teaching was held in the church itself at little cost; from 1712 to 1722 in an unidentified building with a very spacious chamber, belonging to the parish .. under which are two large rooms, possibly an extension to the church.[12] From 1722 to 1729 the school was in a new seven-room house at Springfield used to house the schoolmaster and a schoolroom; after 1729, the two top floors of the Poorhouse were used.[13] The raising of these enormous sums of money over a twenty year period reflects George Miller's powers of persuasion, his contacts and his persistence.

Box Church Restored 1713

In the middle of the school project, George launched a major rebuilding of Box Church in 1713.[14] The north aisle was substantially rebuilt and a large buttress added: windows were installed on both sides of the north door; the east end of the north aisle was made to incorporate the Hazelbury chapel with its 14th century window; and the west end of the north aisle improved. George later said that the aisle holds more than 100 (people).[15] In the chancel, the south and east walls were replaced with a 14th century window (now with Victorian stained glass and called the Pinchin Memorial window) being retained in the east wall.

The work may also have involved internal alterations. Two first floor rooms were removed believed to have been the old Church Chambers where the ecclesiastic court would have met at regular intervals to adjudicate wills, marriages and the work of the churchwardens. It is probable that the old pews were recovered, in red or green baize, studded with brass nails and with a candle bracket at each end. The high pews were let to important families in the village on leasehold or copyhold terms, almost as if they were owned.[16] They enabled some members of the congregation to make an entrance, be dutiful in the privacy of their pew for a short time, then exit without attending the whole service. In later years Box Church was described as crowded with hideous pews and with more hideous galleries carried up nearly to the roof with access to one through a window.[17]

These two photos show the interior of the nave with its high pews prior to the 1896 restoration (courtesy St Thomas à Becket Church brochure).

Georgian proprietorship can also be sensed from the memorials in the church. The old memorials to Sir George Speke (died 1682) and Francis Speke (died 1683) are prominent and they were added to with a brass plate to Thomas Goddard of Rudloe 1703, a dedication to John Rawlings, Senior, 1713, and a memorial to the Neat family of Middlehill.[18]

It was a massive and costly undertaking. George wrote in 1713 that his time since Lady Day last (25 March) has been taken up in rebuilding the Parish Church from the ground, which was opened with great solemnity on All Saints Day (1 November).[19] The new building was a spectacular success. George claimed in 1717 that Our church is now so filled that we have scarce room enough to contain the people. He made it a place that villagers could be proud of and stay to enjoy more of the service.

Springfield Cottages, 1719

George appointed a full-time teacher to take responsibility for the children's education which expanded beyond traditional reading and writing. He started a school choir many of them not being above eight years of age, standing in full view possibly in the gallery, singing two or three psalms before Sunday afternoon service and the like performance after it was over. [20]

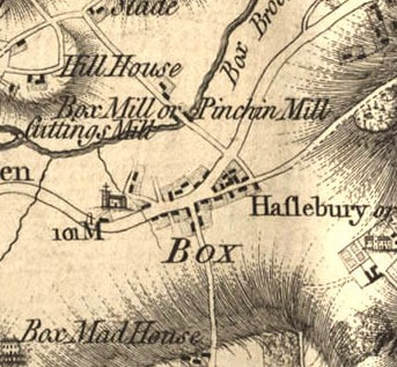

George started to fundraise for a house to be built next to the church at the area we now call Springfield. The land was given by Thomas Speke and John Ford forewent part of his garden to enable the property to be extended for a schoolroom. As we can see from the map shown further below left, the area was substantially altered with the By Brook being diverted away from the area around the church and the track down from The Bear being improved.

Poorhouse, 1727

Box Poorhouse (now called Springfield House) was begun in 1727 in response to an Act of Parliament of 1722 encouraging parishes to rent or own a workhouse for the poor.[21] For a century, the poor had been encouraged to work at home through the issue of materials (such as flax, hemp, wool, thread and iron) with which they could produce goods to be sold for their maintenance. Henceforth this relief was to be limited to those people actually lodging in the institution. The three-storey development was a bold and costly venture, a symbol of a self-supporting community, not unique in the area because Corsham converted four cottages for its poorhouse in 1728, but the scale and grandeur of Springfield House is still impressive today.

The intention behind the Poorhouse reflected the teachings of John Locke enabling inmates to make a meaningful contribution to society. When it opened, it included a workroom, kitchen, brew-house, washhouse, and a separate room for the Master.[22] The workroom was primarily devoted to cloth-making and included twelve spinning wheels, two looms and two scribbling horses for combing the wool. Two hour-glasses were included in the workroom to ensure the inmates worked their full time. The kitchen prepared its own food with a meat block and cleaver, two saltboxes for preserving the food, and the usual kitchen utensils including a rowling pin. Malt beer was made in the brew-house with the mashing tub and stick.

Life inside the house was structured but not oppressive. Men and women were issued with standard clothing. For men, this included shoes with buckles made on the premises, an apron for working and a biggin (night-cap). For females there was also a handkerchief and comb, and two blankets. Recreation facilities comprised The Bible, The Whole Duty of Man, two Common Prayer Books and two New Testaments. An indication of life within the workhouse can be inferred from the costs incurred:

Worsted and needles for the poor learning to knit; A lock and chain for a lunatic; Vagrant put to bed in the workhouse .. Mr Mullin’s Sexton for (attending) her stillborn child.

Those who went into the Poorhouse were required to identify themselves: upon the shoulder of the right sleeve of the uppermost Garment, legally (to) wear, in an open and visible manner, a "Badge or Mark" with a large Roman P, together with the first letter of the name of the parish, cut in red or blue cloth.[23] We find out in the records of April 1728 that the original colour for Box Poorhouse was blue, Paid for some blue cloth to make Badges for the Poor People.[24]

Contributions for the Projects

George Miller obviously used all the contacts he could interest in contributing money to the causes. The Eyre family appear to be local, a branch of the family of the barrister and Member of Parliament for Downton, Salisbury. Henry Hoare of Stourton (now called Stourhead) was a second generation partner in the oldest bank in England, which actually made money in the South Sea Bubble collapse in 1720.

Some of this money probably came from the slave trade. While not directly involved with the trading of slaves, one contributor, Pauncefoot Miller of Jamaica, supplied goods to slaving merchants. The use of money from this vile trade is not surprising as it is estimated that up to 1-in-5 of Britain's wealthy families had significant links to slavery, mostly through the ownership of slaves in the plantations, which were left to widows as an investment.[25] Hoare Bank was associated with financial dealings concerning the slave trade.[26]

One of the issues that taxed the Georgians was how the gentry (gentlemen) could be recognised. Money was not a good indicator because manufacturing men now had access to wealth. In order to differentiate the nouveau riche from the old, behaviour, politeness, morals and even names became the criteria. People's status was determined by their perfume, their interest in culture and their donation to charity.

A considerable amount of the money came from the parish rates, and put considerable strain on local resources. In October 1728 funds of £50 were raised by a special poor rate and a loan of £200 was agreed.[27] The Vestry minutes reported, The burden of the poor (rate) had increased very much, the more for the want of the benefit of the workhouse, begun but not yet finished. Later an additional rate of 1d in £1 was set for the next 38 months to raise funds of £252.7s.8d to enable the Poorhouse to be completed before Easter 1729.

It was a massive and costly undertaking. George wrote in 1713 that his time since Lady Day last (25 March) has been taken up in rebuilding the Parish Church from the ground, which was opened with great solemnity on All Saints Day (1 November).[19] The new building was a spectacular success. George claimed in 1717 that Our church is now so filled that we have scarce room enough to contain the people. He made it a place that villagers could be proud of and stay to enjoy more of the service.

Springfield Cottages, 1719

George appointed a full-time teacher to take responsibility for the children's education which expanded beyond traditional reading and writing. He started a school choir many of them not being above eight years of age, standing in full view possibly in the gallery, singing two or three psalms before Sunday afternoon service and the like performance after it was over. [20]

George started to fundraise for a house to be built next to the church at the area we now call Springfield. The land was given by Thomas Speke and John Ford forewent part of his garden to enable the property to be extended for a schoolroom. As we can see from the map shown further below left, the area was substantially altered with the By Brook being diverted away from the area around the church and the track down from The Bear being improved.

Poorhouse, 1727

Box Poorhouse (now called Springfield House) was begun in 1727 in response to an Act of Parliament of 1722 encouraging parishes to rent or own a workhouse for the poor.[21] For a century, the poor had been encouraged to work at home through the issue of materials (such as flax, hemp, wool, thread and iron) with which they could produce goods to be sold for their maintenance. Henceforth this relief was to be limited to those people actually lodging in the institution. The three-storey development was a bold and costly venture, a symbol of a self-supporting community, not unique in the area because Corsham converted four cottages for its poorhouse in 1728, but the scale and grandeur of Springfield House is still impressive today.

The intention behind the Poorhouse reflected the teachings of John Locke enabling inmates to make a meaningful contribution to society. When it opened, it included a workroom, kitchen, brew-house, washhouse, and a separate room for the Master.[22] The workroom was primarily devoted to cloth-making and included twelve spinning wheels, two looms and two scribbling horses for combing the wool. Two hour-glasses were included in the workroom to ensure the inmates worked their full time. The kitchen prepared its own food with a meat block and cleaver, two saltboxes for preserving the food, and the usual kitchen utensils including a rowling pin. Malt beer was made in the brew-house with the mashing tub and stick.

Life inside the house was structured but not oppressive. Men and women were issued with standard clothing. For men, this included shoes with buckles made on the premises, an apron for working and a biggin (night-cap). For females there was also a handkerchief and comb, and two blankets. Recreation facilities comprised The Bible, The Whole Duty of Man, two Common Prayer Books and two New Testaments. An indication of life within the workhouse can be inferred from the costs incurred:

Worsted and needles for the poor learning to knit; A lock and chain for a lunatic; Vagrant put to bed in the workhouse .. Mr Mullin’s Sexton for (attending) her stillborn child.

Those who went into the Poorhouse were required to identify themselves: upon the shoulder of the right sleeve of the uppermost Garment, legally (to) wear, in an open and visible manner, a "Badge or Mark" with a large Roman P, together with the first letter of the name of the parish, cut in red or blue cloth.[23] We find out in the records of April 1728 that the original colour for Box Poorhouse was blue, Paid for some blue cloth to make Badges for the Poor People.[24]

Contributions for the Projects

George Miller obviously used all the contacts he could interest in contributing money to the causes. The Eyre family appear to be local, a branch of the family of the barrister and Member of Parliament for Downton, Salisbury. Henry Hoare of Stourton (now called Stourhead) was a second generation partner in the oldest bank in England, which actually made money in the South Sea Bubble collapse in 1720.

Some of this money probably came from the slave trade. While not directly involved with the trading of slaves, one contributor, Pauncefoot Miller of Jamaica, supplied goods to slaving merchants. The use of money from this vile trade is not surprising as it is estimated that up to 1-in-5 of Britain's wealthy families had significant links to slavery, mostly through the ownership of slaves in the plantations, which were left to widows as an investment.[25] Hoare Bank was associated with financial dealings concerning the slave trade.[26]

One of the issues that taxed the Georgians was how the gentry (gentlemen) could be recognised. Money was not a good indicator because manufacturing men now had access to wealth. In order to differentiate the nouveau riche from the old, behaviour, politeness, morals and even names became the criteria. People's status was determined by their perfume, their interest in culture and their donation to charity.

A considerable amount of the money came from the parish rates, and put considerable strain on local resources. In October 1728 funds of £50 were raised by a special poor rate and a loan of £200 was agreed.[27] The Vestry minutes reported, The burden of the poor (rate) had increased very much, the more for the want of the benefit of the workhouse, begun but not yet finished. Later an additional rate of 1d in £1 was set for the next 38 months to raise funds of £252.7s.8d to enable the Poorhouse to be completed before Easter 1729.

The maps above show the great changes in the centre of the village. Left: The abundant springs and pool in 1626 (illustrated left by Francis Allen) and

Right: The residential area in 1773 (illustrated by Andrews and Dury). Both maps courtesy Wiltshire History Centre.

Right: The residential area in 1773 (illustrated by Andrews and Dury). Both maps courtesy Wiltshire History Centre.

Conclusion

The work between 1708 and 1729 reflected a pride in the village community from a new sort of people, the gentry whose money derived from trade and finance. As a man of culture and sensitivity in the ranks of the village elite, George preferred the refined and classically-sounding name Millard, rather than Miller which was the name of a common corn-grinder. This was common at the time when gentlemen were identifiable by their knowledge of Greek and Roman culture and formed a distinct elite with people of similar status. It was very different to the power of barons in the middle ages and the inherited status of the nobility.

Box's development was not unique but reflected trends in English society. There is a contemporary report of 29 schools in Wiltshire, written in 1720: Box, a School erected very early, viz in 1708, for 30 poor Children, who are taught to read, write, and say the Catechism, and some Collects out of the Common Prayer Book. The Minister preaches a Charity Sermon every Year, and gives his Easter-Offerings to uphold this Design... Several of the Children have been put out to Husbandmen and Trades.[28]

The work between 1708 and 1729 reflected a pride in the village community from a new sort of people, the gentry whose money derived from trade and finance. As a man of culture and sensitivity in the ranks of the village elite, George preferred the refined and classically-sounding name Millard, rather than Miller which was the name of a common corn-grinder. This was common at the time when gentlemen were identifiable by their knowledge of Greek and Roman culture and formed a distinct elite with people of similar status. It was very different to the power of barons in the middle ages and the inherited status of the nobility.

Box's development was not unique but reflected trends in English society. There is a contemporary report of 29 schools in Wiltshire, written in 1720: Box, a School erected very early, viz in 1708, for 30 poor Children, who are taught to read, write, and say the Catechism, and some Collects out of the Common Prayer Book. The Minister preaches a Charity Sermon every Year, and gives his Easter-Offerings to uphold this Design... Several of the Children have been put out to Husbandmen and Trades.[28]

References

[1] https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2015/11/20/the-faith-of-georgian-england/

[2] Matthew 25:14-30

[3] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750 - 1965, 1979, Wayland Publishers Ltd, p.5, quoting the Duke of Newcastle's advice to Charles II in 1660

[4] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750 - 1965, 1979, p.6

[5] http://www.theclergydatabase.org.uk/jsp/persons/DisplayCcePerson.jsp?PersonID=53133 and Steven Hobbs, Gleanings from Wiltshire Parish Registers, 2010, Wiltshire Record Society, p.21

[6] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.33-46

[7] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.37

[8] Wiltshire Record Society, Volume 56, p.44

[9] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.245

[10] See John Ayers, B-Ed Course, A Christian & Useful Education, Wiltshire History Centre Ref 2265

[11] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLV, p.342-9

[12] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.34

[13] Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England - Wiltshire, 1975, Penguin Books, p.124

[14] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, Guided Tour and A Brief History of St Thomas à Becket Church, Box, 1984

[15] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.38

[16] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.98

[17] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, Guided Tour and A Brief History of St Thomas à Becket Church, Box, 1984

[18] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, 1987, p.37

[19] John Ayers, B-Ed Course, A Christian & Useful Education, Wiltshire History Centre Ref 2265, p.11

[20] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.38-40

[21] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.86 on

[22] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, p.86

[23] Rev Canon Goddard, Appointment of Overseers, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXI, p.395 referring to general instruction by Wiltshire Justices of the Peace in 1755

[24] A Shaw Mellor, Extracts from the Accounts of the Overseers of Box, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLV , p.344

[25] University College London, Legacies of British Slave-ownership, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/search/

[26] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, 1987, p.18

[27] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, p.84

[28] Rev J Cox and A Hally, New Survey of Gt. Britain, Collected and composed by an Impartial Hand, 1720-31, p.198

[1] https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2015/11/20/the-faith-of-georgian-england/

[2] Matthew 25:14-30

[3] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750 - 1965, 1979, Wayland Publishers Ltd, p.5, quoting the Duke of Newcastle's advice to Charles II in 1660

[4] Christopher Martin, A Short History of English Schools 1750 - 1965, 1979, p.6

[5] http://www.theclergydatabase.org.uk/jsp/persons/DisplayCcePerson.jsp?PersonID=53133 and Steven Hobbs, Gleanings from Wiltshire Parish Registers, 2010, Wiltshire Record Society, p.21

[6] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.33-46

[7] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.37

[8] Wiltshire Record Society, Volume 56, p.44

[9] GJ Kidston, History of the Manor of Hazelbury, 1936, p.245

[10] See John Ayers, B-Ed Course, A Christian & Useful Education, Wiltshire History Centre Ref 2265

[11] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLV, p.342-9

[12] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.34

[13] Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England - Wiltshire, 1975, Penguin Books, p.124

[14] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, Guided Tour and A Brief History of St Thomas à Becket Church, Box, 1984

[15] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.38

[16] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton, p.98

[17] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, Guided Tour and A Brief History of St Thomas à Becket Church, Box, 1984

[18] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, 1987, p.37

[19] John Ayers, B-Ed Course, A Christian & Useful Education, Wiltshire History Centre Ref 2265, p.11

[20] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXI, p.38-40

[21] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.86 on

[22] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, p.86

[23] Rev Canon Goddard, Appointment of Overseers, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXI, p.395 referring to general instruction by Wiltshire Justices of the Peace in 1755

[24] A Shaw Mellor, Extracts from the Accounts of the Overseers of Box, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XLV , p.344

[25] University College London, Legacies of British Slave-ownership, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/search/

[26] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket Box, 1987, p.18

[27] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, p.84

[28] Rev J Cox and A Hally, New Survey of Gt. Britain, Collected and composed by an Impartial Hand, 1720-31, p.198