Great Expectations Alan Payne December 2021

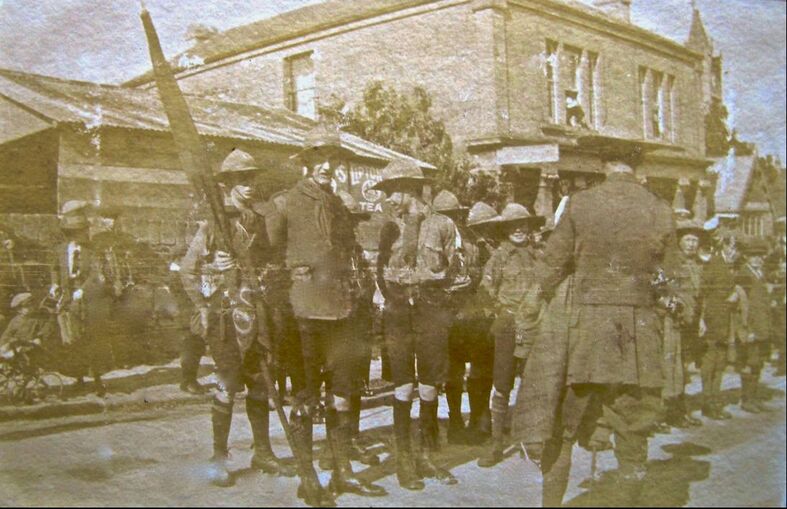

These fabulous photos are a unique record of Box shortly after the First World War. The inter-war years started with high hopes for a peaceful and prosperous future. There had been full employment during the war and low-paid jobs for women (such as domestic service) were on the decline being replaced by clerical and other office work. Malnutrition had been exposed as an evil because of the need for healthy servicemen and women. Optimism particularly affected the young who no longer were in danger of being called up. The years after the Great War were seen as the start of a new beginning of hope and opportunity for the long-term future; not, of course, just an interim period between two world wars.

Expressions of Optimism

The end of the war had many slogans expressing optimism: War to End All Wars, Land fit for Heroes and Homes for Heroes – all used successfully to recruit servicemen and maintain morale during the war. The author HG Wells coined the phrase War to End All Wars early in the war and used it in newspaper articles to mean that, if Britain defeated Germany militarism, it would be a step towards abolishing warfare and establishing a new and better world order. The war was an expression of British imperial power. Many people concluded that victory confirmed the Edwardian perception that Britain was inherently good. Britain was the only great imperial power to survive the war intact whilst Germany, Russia, the Hapsburg and Ottoman Empire states all crumbled. Wells was promoting a world order of peace to fit his socialist views, now sounding more idealistic than achievable. The phrase became increasingly discredited during the atrocities of the war. After the war, little was achieved of the expectation that opportunities – not least for women - and social conditions would be better for the working-class war heroes.

Expressions of Optimism

The end of the war had many slogans expressing optimism: War to End All Wars, Land fit for Heroes and Homes for Heroes – all used successfully to recruit servicemen and maintain morale during the war. The author HG Wells coined the phrase War to End All Wars early in the war and used it in newspaper articles to mean that, if Britain defeated Germany militarism, it would be a step towards abolishing warfare and establishing a new and better world order. The war was an expression of British imperial power. Many people concluded that victory confirmed the Edwardian perception that Britain was inherently good. Britain was the only great imperial power to survive the war intact whilst Germany, Russia, the Hapsburg and Ottoman Empire states all crumbled. Wells was promoting a world order of peace to fit his socialist views, now sounding more idealistic than achievable. The phrase became increasingly discredited during the atrocities of the war. After the war, little was achieved of the expectation that opportunities – not least for women - and social conditions would be better for the working-class war heroes.

Many of the political slogans after the Great War had the objective of trying to bind together the coalition government of Conservatives and some Liberals. Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, expressed his optimism for the future with Land fit for Heroes twelve days after the end of hostilities on 23 November 1918. He declared: There is no time to lose. I want us to take advantage of this new spirit. Don't let us waste this victory merely in ringing joybells. Let us make victory the motive power to link the old land up in such measure that it will be nearer the sunshine than ever before, and that at any rate it will lift those who have been living in the dark places to a plateau where they will get the rays of the sun. He was outlining his political manifesto for the general election on 14 December when, on a wave of euphoria, the victorious prime minister won a majority for his coalition partners of an amazing 283 seats. The realities of British life did not live up these bloated expectations and Lloyd George lost the 1922 election to the Conservative Party.

|

Memorial Fete, 1920

There had been considerable debate in Box about how to commemorate the end of hostilities. The debate was still raging in December 1919 about commissioning an Institute to help returning servicemen but that had received little support.[1] In the end, the Box Parish Council settled on a War Memorial on the site of The Bear Green. The proceeds from an event to be held in the summer of 1920 were allocated towards the cost of the War Memorial. The celebrations in Box in 1920 comprised the usual procession and gathering.[2] The Boy Scouts led the procession accompanied by the Corsham Town Prize Band. Then came the multitude in fancy dress, decorated vehicles and the Friendly Societies with their banners. The parade toured the village and gathered at Fete Field (now the location of Bargates) for sports including skittles, and Jenning’s roundabouts with all the fun of the fair. Attractions at Fete Field included two exhibitions of local mechanical waxworks (often just small clockwork toys). The village authorities recognised that children had missed out during the war and efforts were made to get back some measures of normality. Under the control of Dr JP Martin, swimming in the By Brook was organised into a local club, The Box Swimming Club with its own dressing shed and a diving board and the millstream turned into a bathing establishment.[3] In August 1921, it held its first gala attended by large crowds of people gathering on the banks of the brook. There was a diving display by 13-year-old Leslie Tompkins of Swindon and a demonstration of life-saving by Mrs Birkwood and a lot of mutual congratulation, including the presentation of a fountain pen to Dr Martin. |

Property Sales, 1919

It soon became apparent that economic conditions had deteriorated after the war. The stone industry had endured previous recessions, such as that in 1890 when the Bath Stone Firms sold parts of The Market Place to the Methodist quarrying family, Samuel Rowe and Elizabeth Noble. By the end of the war it was apparent that these rental properties were no longer as desirable. On the death of Elizabeth Noble on 31 October 1918, the properties were put up for sale at auction, including Frogmore House & Shop now let at a reduced rental of £21 in the occupation of Mr Tanner, and the four cottages adjoining tenanted by Messrs Ford, Phelps, Wheatley and Johnson.[4] At the same time, the executors of the estate sold the rest of the Noble’s properties, including a block of four stone-built cottages on Chapel Lane and eight stone-built cottages with gardens at Townsend. It was symbolically the end of a chapter in Box’s history, the end of a family so deeply involved in the quarry trade and the United Methodist Chapel.

It soon became apparent that economic conditions had deteriorated after the war. The stone industry had endured previous recessions, such as that in 1890 when the Bath Stone Firms sold parts of The Market Place to the Methodist quarrying family, Samuel Rowe and Elizabeth Noble. By the end of the war it was apparent that these rental properties were no longer as desirable. On the death of Elizabeth Noble on 31 October 1918, the properties were put up for sale at auction, including Frogmore House & Shop now let at a reduced rental of £21 in the occupation of Mr Tanner, and the four cottages adjoining tenanted by Messrs Ford, Phelps, Wheatley and Johnson.[4] At the same time, the executors of the estate sold the rest of the Noble’s properties, including a block of four stone-built cottages on Chapel Lane and eight stone-built cottages with gardens at Townsend. It was symbolically the end of a chapter in Box’s history, the end of a family so deeply involved in the quarry trade and the United Methodist Chapel.

Conclusion

The story of Box in the inter-war years is one of conflicting interests. For some local people, these years became the Roaring Twenties; for other residents, the period became increasingly a time of unemployment and poverty, both trends dealt with in later issues. The desire to return to a pre-war normality proved to be an illusion with many Box men finding their old jobs had disappeared and women no longer content with work in domestic service and as shop girls.

The war also marked a major turning point in traditional sources of power and authority in the village. The status and role of the Lord of the Manor virtually disappeared after the war in favour of the Box Parish Council and a few individuals came to control many village organisations and clubs. As the 1930s evolved, the rise of middle-class residents was striking and widespread poverty gave way to a greater affluence and consumerism. The inter-war years of two decades was some of the most complicated times in the history of the village.

The story of Box in the inter-war years is one of conflicting interests. For some local people, these years became the Roaring Twenties; for other residents, the period became increasingly a time of unemployment and poverty, both trends dealt with in later issues. The desire to return to a pre-war normality proved to be an illusion with many Box men finding their old jobs had disappeared and women no longer content with work in domestic service and as shop girls.

The war also marked a major turning point in traditional sources of power and authority in the village. The status and role of the Lord of the Manor virtually disappeared after the war in favour of the Box Parish Council and a few individuals came to control many village organisations and clubs. As the 1930s evolved, the rise of middle-class residents was striking and widespread poverty gave way to a greater affluence and consumerism. The inter-war years of two decades was some of the most complicated times in the history of the village.

References

[1] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 6 December 1919

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 25 September 1920

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 27 August 1921

[4] The Wiltshire Times, 18 October 1919

[1] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 6 December 1919

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 25 September 1920

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 27 August 1921

[4] The Wiltshire Times, 18 October 1919