|

Their Name Liveth For Evermore:

Box War Memorial Alan Payne August 2018 The Wiltshire Times wrote in October 1920: Dedication of the War Memorial. The parishes of Box and Ditteridge stood well in regard to the number of men who went forth in their country's cause in the Great War, and of that number there was a heavy toll. To honour the memories of those who fell, the parishes have provided a handsome memorial which has been erected in a prominent position at the junction of the Devizes and London Roads.[1] |

Planning the Memorial

After the First World War, the Parish Council and villagers of Box were determined to have a memorial appropriate to the memory of parishioners who had lost their lives in the war. A suitable site was needed and Dr Martin, chairman of the Council, sought a suitable plot of land, eventually agreeing to buy part of the garden of The Glen, sometimes called Bear Green, on behalf of the council.

The collection of names was difficult. Lists honouring the dead were published in the Parish Magazine during the war but decisions had to be made about: how long to wait for the missing to be declared dead; where to honour children who had relocated; and how long after the war should the list be kept open for those who died of wounds. Peace was signed at Versailles in June 1919, months after the Armistice and a list of those to be recorded on the memorial was set up on the High Street for residents' comments. The name of George Milsom, who died of wounds in July 1920, was the last to be included.

After the First World War, the Parish Council and villagers of Box were determined to have a memorial appropriate to the memory of parishioners who had lost their lives in the war. A suitable site was needed and Dr Martin, chairman of the Council, sought a suitable plot of land, eventually agreeing to buy part of the garden of The Glen, sometimes called Bear Green, on behalf of the council.

The collection of names was difficult. Lists honouring the dead were published in the Parish Magazine during the war but decisions had to be made about: how long to wait for the missing to be declared dead; where to honour children who had relocated; and how long after the war should the list be kept open for those who died of wounds. Peace was signed at Versailles in June 1919, months after the Armistice and a list of those to be recorded on the memorial was set up on the High Street for residents' comments. The name of George Milsom, who died of wounds in July 1920, was the last to be included.

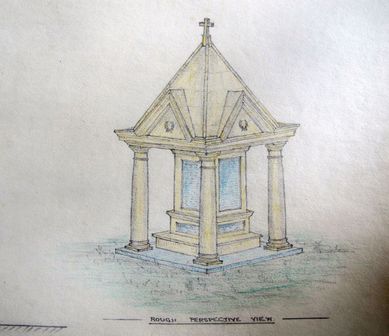

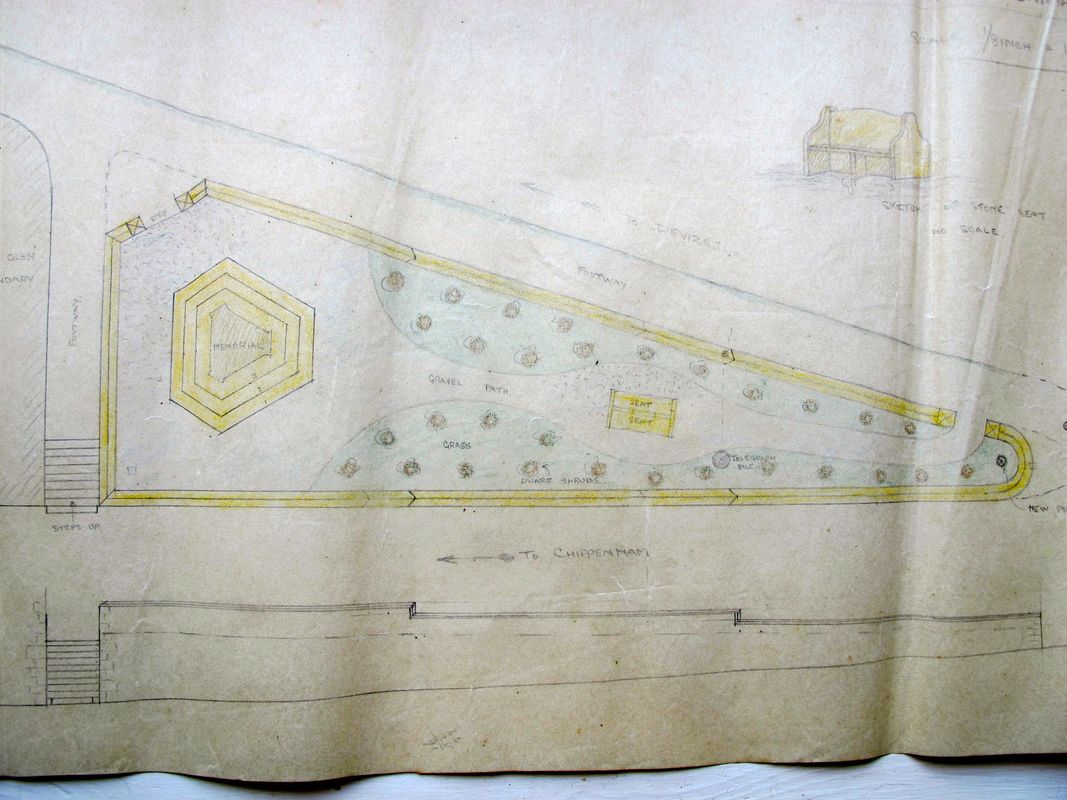

Box villagers were asked to submit designs for the memorial. Cecil Lambert, then aged 25 and newly returned from service in the war, produced some interesting plans (see above, courtesy of Anna Grayson). He suggested rebuilding the London Road wall and widening the junction access to allow a turn right from the Devizes Road down to the east. The memorial would be set up on three steps with a permanent seat and raised lettering and emblems decorated in bronze. He estimated the cost of the work at £530. It was much more than had been raised by residents and financial constraints and the size of the plot resulted in a simpler plan produced by Arthur Chaffey of Charlotte Cottage.

Roll of Honour

The list of names of the fallen proved a much more difficult job than had been expected.[2] The Church sought to confirm full names with relatives and the rank and regiment of the servicemen. By July 1920 there was only one name left for which no information can be supplied, namely E Buck.

In the event, the names of all 43 Box men who died in the First World War are recorded on the memorial. Many of the servicemen were teenagers, little more than children, with poor education and restricted employment opportunities. We have brief obituaries to them at the article Never Forgotten. These listings are remarkably inadequate for the sacrifices made but we remember and honour them.

The Parish Magazine sought to keep residents involved in the decisions and a sketch of the final design was hung in Box Church in July 1920 accompanied by a donations box as the full cost had not been collected. The contract for construction of the memorial was given to Joseph Bell of College Green, Bristol, a curious decision in view of the number of local stone masons but perhaps reflecting how many young quarrymen had been lost in the war.

Inauguration, Saturday 23 October 1920

The inauguration was two weeks before Remembrance Day 1920 to allow relatives of the servicemen to mourn in less crowded conditions. The local newspapers carried an extensive tribute to the memorial in October: Henceforward all wayfarers who approach the village of Box from the west will pass beneath the shadow of a wayside cross.[3] Its mission was the silent admonition to remembrance and its location at the parting of the ways ... of the two roads which lead to London. It will tell over and over again its story of sacrifice, repeating with silent eloquence to all who will heed the message," Is it nothing to you, all ye that pass by?"

A procession through the village from the Schools was headed by the Corsham Brass Band and accompanied by the women's VAD detachment under Mrs Langdon, the boy scouts under Scoutmaster Lambert, parish councillors, ex-servicemen, members of St John's Ambulance and the Friendly Societies. The unveiling from beneath a Union Jack was performed by Mr George Wilbraham Northey, lord of the manor, Mr Perrin played the organ and Rev White, vicar of Box, the Rev P Madge, of the United Methodist Church and the Rev Gordon Tidy, rector of Ditteridge Church conducted an inter-denominational service, ending with the hymn O God, our help in ages past. After the sounding of the Last Post by buglers, Privates Collins and Harris, the National Anthem was sung after which relatives and friends of the fallen placed wreaths at the base.

Vicar William White addressed the gathered crowd saying about those who had returned, Perhaps they would not die for England; then let them live for England and for God, and live better lives for the sake of those who had gone before.

Roll of Honour

The list of names of the fallen proved a much more difficult job than had been expected.[2] The Church sought to confirm full names with relatives and the rank and regiment of the servicemen. By July 1920 there was only one name left for which no information can be supplied, namely E Buck.

In the event, the names of all 43 Box men who died in the First World War are recorded on the memorial. Many of the servicemen were teenagers, little more than children, with poor education and restricted employment opportunities. We have brief obituaries to them at the article Never Forgotten. These listings are remarkably inadequate for the sacrifices made but we remember and honour them.

The Parish Magazine sought to keep residents involved in the decisions and a sketch of the final design was hung in Box Church in July 1920 accompanied by a donations box as the full cost had not been collected. The contract for construction of the memorial was given to Joseph Bell of College Green, Bristol, a curious decision in view of the number of local stone masons but perhaps reflecting how many young quarrymen had been lost in the war.

Inauguration, Saturday 23 October 1920

The inauguration was two weeks before Remembrance Day 1920 to allow relatives of the servicemen to mourn in less crowded conditions. The local newspapers carried an extensive tribute to the memorial in October: Henceforward all wayfarers who approach the village of Box from the west will pass beneath the shadow of a wayside cross.[3] Its mission was the silent admonition to remembrance and its location at the parting of the ways ... of the two roads which lead to London. It will tell over and over again its story of sacrifice, repeating with silent eloquence to all who will heed the message," Is it nothing to you, all ye that pass by?"

A procession through the village from the Schools was headed by the Corsham Brass Band and accompanied by the women's VAD detachment under Mrs Langdon, the boy scouts under Scoutmaster Lambert, parish councillors, ex-servicemen, members of St John's Ambulance and the Friendly Societies. The unveiling from beneath a Union Jack was performed by Mr George Wilbraham Northey, lord of the manor, Mr Perrin played the organ and Rev White, vicar of Box, the Rev P Madge, of the United Methodist Church and the Rev Gordon Tidy, rector of Ditteridge Church conducted an inter-denominational service, ending with the hymn O God, our help in ages past. After the sounding of the Last Post by buglers, Privates Collins and Harris, the National Anthem was sung after which relatives and friends of the fallen placed wreaths at the base.

Vicar William White addressed the gathered crowd saying about those who had returned, Perhaps they would not die for England; then let them live for England and for God, and live better lives for the sake of those who had gone before.

Funding the Work

In the troubled years after the war, arrangements were very local. The Parish Council acquired the plot of ground, the stone was gifted by the Bath Stone Company and the £320 cost of working it was raised by public subscription.[4] The inscription on the lower panel was instigated by the Rev Vere Awdry, father of the creator of Thomas the Tank Engine.

The dedication of the memorial was for the living as well as of the dead. They thought of the hearts that mourned, and the lives that were lonely, and they hoped that such who mourned for the dead saw a little more clearly than many others of them perhaps did.

In the troubled years after the war, arrangements were very local. The Parish Council acquired the plot of ground, the stone was gifted by the Bath Stone Company and the £320 cost of working it was raised by public subscription.[4] The inscription on the lower panel was instigated by the Rev Vere Awdry, father of the creator of Thomas the Tank Engine.

The dedication of the memorial was for the living as well as of the dead. They thought of the hearts that mourned, and the lives that were lonely, and they hoped that such who mourned for the dead saw a little more clearly than many others of them perhaps did.

The memorial was to honour the men who during the Great War 1914-1918 left all that was dear to them at the call of duty, to endure hardship, to face danger, and gave their lives for the freedom of the world. Their name liveth for evermore.[5]

Contemporary reports make it clear that the sacrifice was to resist German aggression and the possibility of invasion: to overthrow spiritual wickedness in high places and to overthrow the doctrine of might and to establish that right is might.[6]

They lost their futures out of their commitment to God and the King and the belief that this was the War to End All Wars. It is the ignominy of their deaths that strikes us most - many were drowned in a sea of mud with their bodies never recovered. The aftermath of the war was chronic unemployment, inadequate housing, and the emergence of racist philosophies that split the world again. Our collective failure to rebuild a better world makes the remembrance more vital. Box villagers have kept their faith by honouring the Remembrance Day Service ever since.

Symbolically, in 1939 Box Parish Council objected to the most disgraceful suggestion to erect traffic lights and two large direction signs right in front of the memorial obscuring the base of the cross.[7] It would spoil the whole aspect of the place. A letter of protest was sent to the London Office of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England. Memories were still very raw.

Contemporary reports make it clear that the sacrifice was to resist German aggression and the possibility of invasion: to overthrow spiritual wickedness in high places and to overthrow the doctrine of might and to establish that right is might.[6]

They lost their futures out of their commitment to God and the King and the belief that this was the War to End All Wars. It is the ignominy of their deaths that strikes us most - many were drowned in a sea of mud with their bodies never recovered. The aftermath of the war was chronic unemployment, inadequate housing, and the emergence of racist philosophies that split the world again. Our collective failure to rebuild a better world makes the remembrance more vital. Box villagers have kept their faith by honouring the Remembrance Day Service ever since.

Symbolically, in 1939 Box Parish Council objected to the most disgraceful suggestion to erect traffic lights and two large direction signs right in front of the memorial obscuring the base of the cross.[7] It would spoil the whole aspect of the place. A letter of protest was sent to the London Office of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England. Memories were still very raw.

|

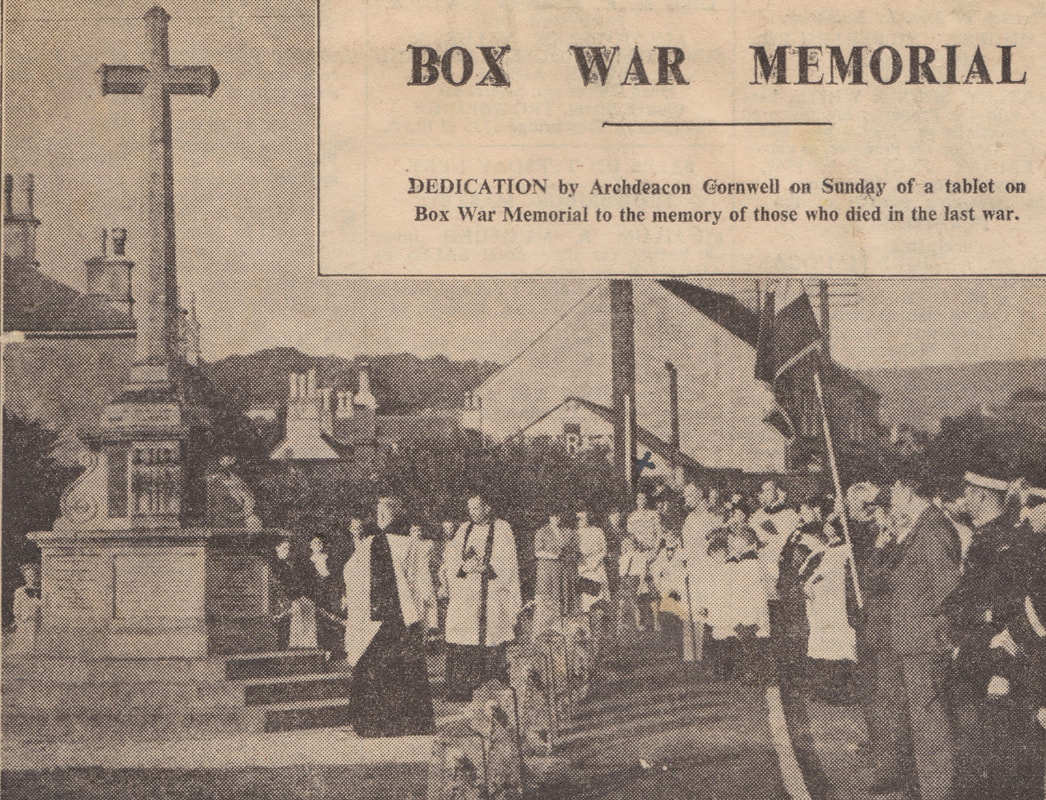

Second World War Additions Box went through the same process of coming to terms with the end of war, grieving the dead and establishing a new life. In July 1949 additions were made to the memorial with three tablets dedicated by the Archdeacon of Swindon, the Venerable LC Cornwall to those who lost their lives in the Second World War.[8] A stone tablet in the church for World War 1, designed by Oswald Brakspear of Corsham, was moved from behind the lectern to the west wall to be on permanent view there alongside another for the Second War. Two rows of pews were removed and families were invited to leave cut flowers on ledges underneath. |

For the War Memorial dedication, the choir and cross-bearer processed from the Church to the memorial for the Archdeacon's dedication. His address referred to the names as the cutting off of hope, the cutting off of plans, of sorrow and tears to be treasured so long as there is anybody living here to who those names are something more than just names.

In 2019 it will be seventy years since the names of a further eighteen servicemen were added to the list in a dedication by the Archdeacon of Swindon. In the Second World War there were 18 fatalities, all men: 12 soldiers, 2 sailors, 1 airman and 3 unknown. Some lost their lives in the Far East, one seems to have died from so-called friendly fire. The list was less certain than in the First World War and there were others who might have been on the list because they had a long-term connection with the village. You can read more about all of these people and others at Servicemen and Women.

In 2019 it will be seventy years since the names of a further eighteen servicemen were added to the list in a dedication by the Archdeacon of Swindon. In the Second World War there were 18 fatalities, all men: 12 soldiers, 2 sailors, 1 airman and 3 unknown. Some lost their lives in the Far East, one seems to have died from so-called friendly fire. The list was less certain than in the First World War and there were others who might have been on the list because they had a long-term connection with the village. You can read more about all of these people and others at Servicemen and Women.

References

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 30 October 1920

[2] Parish Magazine, July 1920

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 30 October 1920

[4] The Wiltshire Times, 30 October 1920

[5] Inscription on the memorial

[6] The Wiltshire Times, 30 October 1920

[7] The Wiltshire Times, 1 July 1939

[8] The Wiltshire Times, 16 July 1949

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 30 October 1920

[2] Parish Magazine, July 1920

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 30 October 1920

[4] The Wiltshire Times, 30 October 1920

[5] Inscription on the memorial

[6] The Wiltshire Times, 30 October 1920

[7] The Wiltshire Times, 1 July 1939

[8] The Wiltshire Times, 16 July 1949