Box versus Napoleon Claire Dimond Mills February 2019

For many people, Napoleon Bonaparte was one of history’s most famous tyrants. Rampaging across Europe with his post-revolution French army, he caused chaos and conflict in his wake. Britain, and its allies, did all they could to stop him, leading to notorious military engagements such as the Battles of Trafalgar and Waterloo. But how did the wars against Napoleon affect the common people of Box and what part did they play in his eventual downfall?

French Revolutionary Wars, 1792 – 1802

Apart from a small period, Britain was at war with France and its Revolutionary Government for over nine years. Most of the war was fought in mainland Europe between the major powers of that time. By the beginning of 1798, only Britain was left to fight the French. In March of that year a number of letters from True Britons appeared lending support to the government and encouraging their fellow man to do their bit by giving parochial contributions. At this important crisis, we are not only threatened with an invasion by an inveterate and exasperated enemy but actual preparations by that enemy are being made unless they are powerfully repelled.[1] There were various arguments in support of giving voluntary contributions to the war effort that: if everyone gave a little together, it would amount to a large sum; it would shorten the length of time that tax would be imposed; and public spirit shown in this way would disconcert the designs of the enemy.[2]

There is no doubt that feelings about the enemy were strong and a need to contribute to their downfall was essential. This was obviously shared by the inhabitants of Box who in April 1798 were thanked by the Mansion House, London, for their donation of £110.10s.6d (over £12,000 in today’s terms) and requested that they continue in their laudable exertions to a cause which involves the existence of the country and the preservation of everything that is valuable in society.[3]

The situation for Britain improved when a new coalition with Austria and the Russian Empire was obtained in late 1798. But there was still the problem of funding the war, which was deeply unpopular with some of the Whig opposition led by Charles James Fox. It was left to the Tory government under Pitt the younger to introduce the new tax on income from property, woodlands, trades and professions at rates from under 1% to 10% in 1798. It was abolished (supposedly) in 1816 but abolition only became permanent after 1842.

After a number of conflicts, the British and French signed the Treaty of Amiens in 1802 ending the war but this was short lived. With Napoleon making changes to the international system of Western Europe and freezing Britain out of European affairs, Britain felt a sense of loss of control, as well as loss of international trading markets, and was also worried by Napoleon's possible threat to its overseas colonies. Britain declared war on France again in May 1803.

French Revolutionary Wars, 1792 – 1802

Apart from a small period, Britain was at war with France and its Revolutionary Government for over nine years. Most of the war was fought in mainland Europe between the major powers of that time. By the beginning of 1798, only Britain was left to fight the French. In March of that year a number of letters from True Britons appeared lending support to the government and encouraging their fellow man to do their bit by giving parochial contributions. At this important crisis, we are not only threatened with an invasion by an inveterate and exasperated enemy but actual preparations by that enemy are being made unless they are powerfully repelled.[1] There were various arguments in support of giving voluntary contributions to the war effort that: if everyone gave a little together, it would amount to a large sum; it would shorten the length of time that tax would be imposed; and public spirit shown in this way would disconcert the designs of the enemy.[2]

There is no doubt that feelings about the enemy were strong and a need to contribute to their downfall was essential. This was obviously shared by the inhabitants of Box who in April 1798 were thanked by the Mansion House, London, for their donation of £110.10s.6d (over £12,000 in today’s terms) and requested that they continue in their laudable exertions to a cause which involves the existence of the country and the preservation of everything that is valuable in society.[3]

The situation for Britain improved when a new coalition with Austria and the Russian Empire was obtained in late 1798. But there was still the problem of funding the war, which was deeply unpopular with some of the Whig opposition led by Charles James Fox. It was left to the Tory government under Pitt the younger to introduce the new tax on income from property, woodlands, trades and professions at rates from under 1% to 10% in 1798. It was abolished (supposedly) in 1816 but abolition only became permanent after 1842.

After a number of conflicts, the British and French signed the Treaty of Amiens in 1802 ending the war but this was short lived. With Napoleon making changes to the international system of Western Europe and freezing Britain out of European affairs, Britain felt a sense of loss of control, as well as loss of international trading markets, and was also worried by Napoleon's possible threat to its overseas colonies. Britain declared war on France again in May 1803.

Threat of French Invasion

The threat of French invasion of Britain became real in 1797 when in February 1,400 Republican troops landed at Fishguard, Wales, intending a march on Bristol or Liverpool. The local militia and the Pembroke Yeomanry Cavalry were called out and the invaders were quickly captured together with their ships. It has been called the last military battle fought on British soil by a foreign invader. That wasn’t the end of the matter, however, because the incident sparked a run on the pound at the Bank of England with people wishing to exchange their bank notes for gold. Parliament was forced to refuse such conversion from 1797 until 1827.

Other French plans included attacks on Newcastle, which may have sparked the legend of the Hartlepool monkey during the Napoleonic Wars. A French ship was sighted off the coast, in distress, eventually sinking and a sole survivor was captured on the beach wearing parts of a military uniform. Allegedly, the townsfolk captured him, held a beach trial and hanged him, only to discover later that he wasn’t French at all but was a monkey kept on board the boat as the crew’s mascot. Legend or not, the story reflects the fear of invasion at this time.

The threat of French invasion of Britain became real in 1797 when in February 1,400 Republican troops landed at Fishguard, Wales, intending a march on Bristol or Liverpool. The local militia and the Pembroke Yeomanry Cavalry were called out and the invaders were quickly captured together with their ships. It has been called the last military battle fought on British soil by a foreign invader. That wasn’t the end of the matter, however, because the incident sparked a run on the pound at the Bank of England with people wishing to exchange their bank notes for gold. Parliament was forced to refuse such conversion from 1797 until 1827.

Other French plans included attacks on Newcastle, which may have sparked the legend of the Hartlepool monkey during the Napoleonic Wars. A French ship was sighted off the coast, in distress, eventually sinking and a sole survivor was captured on the beach wearing parts of a military uniform. Allegedly, the townsfolk captured him, held a beach trial and hanged him, only to discover later that he wasn’t French at all but was a monkey kept on board the boat as the crew’s mascot. Legend or not, the story reflects the fear of invasion at this time.

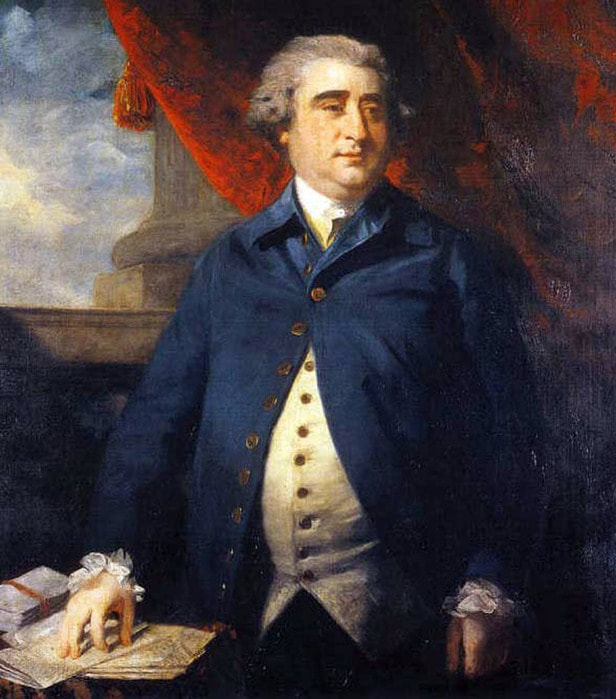

The participants: L to R, Charles James Fox, Pitt the Younger, and Napoleon (all courtesy Wikipedia)

Napoleonic Wars, 1803 - 1815

The whole of Britain was swept with enthusiasm to defend their homes against the French forces as they gradually took over most of mainland Europe. Wearing their own improvised uniforms, local men formed themselves into motley crews of local Volunteers, fuelled by xenophobia and jingoism. The government felt obliged to make proper arrangements and following an Act of Parliament in 1798 every man aged between 17 and 55 was asked to serve as a Volunteer, agreeing to be trained and exercised and sent on march to any part of Great Britain in case of actual invasion or of appearance of the enemy in force upon the coast. Service out of the locality was deeply unpopular and in a letter to the Box Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor dated 2 August 1803, it was explained that Formation of the volunteer corps is highly desirable and of greatest importance at this momentous crisis, a most effectual means of concentrating the national force.

The Volunteers were formed into corps, officered by respectable gentlemen in their own neighbourhood, and intended to be armed by the government. Plans for drilling the Volunteers were also sent out with a request that any local man with a military line of service be flagged up to Matthew Humphreys of Ivy House, the appointed lieutenant of the Chippenham division, so they could help with training. Drill practice was to take place twice a week, usually on a Sunday as this was the only day men would be released from work before or after the church service.[4] The Overseers were also told in the letter that there will be difficulty in issuing arms from His Majesties stores for training, without injury to other branches of the military service so I (Lord Hobart) am directed to resort to the zeal and public spirit of the inhabitants in procuring a return of the arms in their possession. 25 firelocks are considered sufficient for drilling 100 men.[5]

There is a lovely portrayal of the training of the Volunteers in Thomas Hardy’s novel The Trumpet Major. He focused on the ridiculous aspect of the training for those who didn’t have their own weapons: You middle men, that are armed with hurdle-sticks and cabbage-stumps just to make believe, must of course use ‘em as if they were the real thing.[6] Hardy also noted that each man was paid for their attendance at the training. In a letter to the Box Overseers dated 4 August 1803, payment was explained – 20 shillings per man for clothing once in every 3 years, 1 shilling per day for 20 days exercise per year. Men will not be paid their shilling if they hadn’t attended the Sunday before, unless ill. The last paragraph of the letter told the Overseers not to complain about the money!

Box’s Volunteer Corps

By November 1803, the threat of invasion had become so serious that another letter was sent to Rev Isaac William Horlock, this time asking each parish to make preparatory arrangements for abandoning the village and fleeing to a safer location.[7] Cattle was to be marked with the owner’s initials and a second distinguishing mark common to the parish. A place of rendezvous was to be decided where all the horses, cattle, sheep, waggons, carts and carriages (not wanted for service and supply of king’s troops) could be conveyed away. Removal of stock was ordered in the southern and eastern parts of this county owing to their proximity to the British Channel. Transport had to go across open fields and not on turnpike or principal roads.

The effect of the war on the general public began to cause severe hardship. Rural unemployment following Georgian improvement schemes and the continuing enclosure of land by landowners were long-term changes in the countryside. Repeated poor harvests in the 1790s caused widespread food shortages and fast-rising prices. In an attempt to deal with the problem, the government issued instructions and a new term came into general use, allotments, meaning the setting aside of portions of land in strips to enable the poor to cultivate food for themselves. The scheme was to be administered by the Overseers of the Poor, headed by the Inspector of Allotments, Rev Horlock.

The allotment system was for the fit and healthy and the vicar was also made responsible for arranging the removal out of the village of those inhabitants who were incapable of removing themselves by reason of infancy, age, or infirmity. Such people were to take with them only portable effects such as money, securities, apparel, plate, linen, books of accounts, and a small quantity of salted or dried provisions.

Role of the Pioneers

The Pioneers were completely different to the Volunteers. They were servicemen in the army, with a specific role to undertake heavy engineering duties. Because the government thought that local volunteers wouldn’t comply with a scorched-earth policy, they wanted the Overseers to establish local Pioneer groups. The Overseers were asked to make arrangements for the removal of waggons, cattle, horses and livestock out of local areas, to be provisioned by charging the proprietors themselves.

If the enemy should unexpectedly advance into the area, and it was impossible to remove all or part of the livestock, then standing instructions were to be followed expressly issued by His Majesty the King. These included that horses or draft cattle should be shot, or ham strung, if they were in evident danger of falling into the hands of the enemy; and that axle trees or wheels of all carriages should be broken to pieces or damaged as much as possible. Indemnification was to be given to the proprietors for the losses they sustained by the execution of these measures. But if they negligently, or for want of proper exertion, allowed serviceable horses, cattle or carriages to fall into enemy hands they weren’t eligible for compensation.

James Cottle, labourer, the local Captain of the Pioneers, with Superintendents appointed by Rev Horlock to overview matters being:

Mr William Brown, yeoman farmer, who had lost an eye;

Jonathon Lee, also yeoman with 1300 sheep;

Isaac Kingston, overage at 55+ but with status in the parish;

Thomas Jones, younger than his fellows, who was the Tythingman (constable); and

George Mullins, schoolmaster.

At a meeting on Christmas Day 1803, these men decided that Kingsdown would be the rendezvous point, and that a circle with the letters BX inside would be the parish mark for cattle. Local flour millers, George Young, Samuel Pinchin and Edward Baldwin, were engaged to make 36 bags of flour and bakers, George Phillips, Paul Wiltshire, and John Jones, were engaged to make 2,160 3-pound loaves every day. Box was ready for invasion.

The whole of Britain was swept with enthusiasm to defend their homes against the French forces as they gradually took over most of mainland Europe. Wearing their own improvised uniforms, local men formed themselves into motley crews of local Volunteers, fuelled by xenophobia and jingoism. The government felt obliged to make proper arrangements and following an Act of Parliament in 1798 every man aged between 17 and 55 was asked to serve as a Volunteer, agreeing to be trained and exercised and sent on march to any part of Great Britain in case of actual invasion or of appearance of the enemy in force upon the coast. Service out of the locality was deeply unpopular and in a letter to the Box Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor dated 2 August 1803, it was explained that Formation of the volunteer corps is highly desirable and of greatest importance at this momentous crisis, a most effectual means of concentrating the national force.

The Volunteers were formed into corps, officered by respectable gentlemen in their own neighbourhood, and intended to be armed by the government. Plans for drilling the Volunteers were also sent out with a request that any local man with a military line of service be flagged up to Matthew Humphreys of Ivy House, the appointed lieutenant of the Chippenham division, so they could help with training. Drill practice was to take place twice a week, usually on a Sunday as this was the only day men would be released from work before or after the church service.[4] The Overseers were also told in the letter that there will be difficulty in issuing arms from His Majesties stores for training, without injury to other branches of the military service so I (Lord Hobart) am directed to resort to the zeal and public spirit of the inhabitants in procuring a return of the arms in their possession. 25 firelocks are considered sufficient for drilling 100 men.[5]

There is a lovely portrayal of the training of the Volunteers in Thomas Hardy’s novel The Trumpet Major. He focused on the ridiculous aspect of the training for those who didn’t have their own weapons: You middle men, that are armed with hurdle-sticks and cabbage-stumps just to make believe, must of course use ‘em as if they were the real thing.[6] Hardy also noted that each man was paid for their attendance at the training. In a letter to the Box Overseers dated 4 August 1803, payment was explained – 20 shillings per man for clothing once in every 3 years, 1 shilling per day for 20 days exercise per year. Men will not be paid their shilling if they hadn’t attended the Sunday before, unless ill. The last paragraph of the letter told the Overseers not to complain about the money!

Box’s Volunteer Corps

By November 1803, the threat of invasion had become so serious that another letter was sent to Rev Isaac William Horlock, this time asking each parish to make preparatory arrangements for abandoning the village and fleeing to a safer location.[7] Cattle was to be marked with the owner’s initials and a second distinguishing mark common to the parish. A place of rendezvous was to be decided where all the horses, cattle, sheep, waggons, carts and carriages (not wanted for service and supply of king’s troops) could be conveyed away. Removal of stock was ordered in the southern and eastern parts of this county owing to their proximity to the British Channel. Transport had to go across open fields and not on turnpike or principal roads.

The effect of the war on the general public began to cause severe hardship. Rural unemployment following Georgian improvement schemes and the continuing enclosure of land by landowners were long-term changes in the countryside. Repeated poor harvests in the 1790s caused widespread food shortages and fast-rising prices. In an attempt to deal with the problem, the government issued instructions and a new term came into general use, allotments, meaning the setting aside of portions of land in strips to enable the poor to cultivate food for themselves. The scheme was to be administered by the Overseers of the Poor, headed by the Inspector of Allotments, Rev Horlock.

The allotment system was for the fit and healthy and the vicar was also made responsible for arranging the removal out of the village of those inhabitants who were incapable of removing themselves by reason of infancy, age, or infirmity. Such people were to take with them only portable effects such as money, securities, apparel, plate, linen, books of accounts, and a small quantity of salted or dried provisions.

Role of the Pioneers

The Pioneers were completely different to the Volunteers. They were servicemen in the army, with a specific role to undertake heavy engineering duties. Because the government thought that local volunteers wouldn’t comply with a scorched-earth policy, they wanted the Overseers to establish local Pioneer groups. The Overseers were asked to make arrangements for the removal of waggons, cattle, horses and livestock out of local areas, to be provisioned by charging the proprietors themselves.

If the enemy should unexpectedly advance into the area, and it was impossible to remove all or part of the livestock, then standing instructions were to be followed expressly issued by His Majesty the King. These included that horses or draft cattle should be shot, or ham strung, if they were in evident danger of falling into the hands of the enemy; and that axle trees or wheels of all carriages should be broken to pieces or damaged as much as possible. Indemnification was to be given to the proprietors for the losses they sustained by the execution of these measures. But if they negligently, or for want of proper exertion, allowed serviceable horses, cattle or carriages to fall into enemy hands they weren’t eligible for compensation.

James Cottle, labourer, the local Captain of the Pioneers, with Superintendents appointed by Rev Horlock to overview matters being:

Mr William Brown, yeoman farmer, who had lost an eye;

Jonathon Lee, also yeoman with 1300 sheep;

Isaac Kingston, overage at 55+ but with status in the parish;

Thomas Jones, younger than his fellows, who was the Tythingman (constable); and

George Mullins, schoolmaster.

At a meeting on Christmas Day 1803, these men decided that Kingsdown would be the rendezvous point, and that a circle with the letters BX inside would be the parish mark for cattle. Local flour millers, George Young, Samuel Pinchin and Edward Baldwin, were engaged to make 36 bags of flour and bakers, George Phillips, Paul Wiltshire, and John Jones, were engaged to make 2,160 3-pound loaves every day. Box was ready for invasion.

Additional Army Recruits and the Militia

At the start of the French Revolutionary Wars, the total size of the British Army was only 40,000 men which was gradually increased by 1815 to 250,000 servicemen, despite the huge number of fatalities especially in the Peninsula War after 1807. Originally the militia (who we nowadays call Reservists) were independent of the national standing army. They were selected by local ballot and paid for out of local rates, wore red uniforms, when called up, and, most importantly, they never served in their own county.

The invasion by Napoleon’s troops didn’t happen, but it still continued to be a threat for several more years resulting in more government requests for support. The Act of 29th June 1804 decreed a need for establishing and maintaining a permanent additional force for the defence of the realm and for the gradual reduction of the militia of England. In November 1804, Box had to raise a quota of three men for this permanent additional force or pay a £20 fine before 13 November 1804. John Parsons, James Garlick and Thomas Woodham were enlisted, and the Overseers got 1 guinea per man provided. However, a handwritten note explains that Thomas Woodham was discharged as deficient which might explain why a few weeks later Box was notified that it was short of one man and the Overseers had to produce him to the White Horse Inn, Chippenham, on Monday 12 November at 11 o’clock to be then enrolled to serve in the permanent additional force. They must have failed to do this as another handwritten note says that Mr Gisford, Box Overseer paid a twenty pounds fine as they were unable to supply the man.

The decisive naval victory for the British at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 saw the threat of invasion diminish somewhat but in 1808 when the Peninsular Campaign in Spain and Portugal began, the Government saw the need to enable a local militia force to be called forth and employed in case of invasion to aid His Majesty’s regular militia. Men between 18 and 30 selected by ballot enrolled for four-year period of service. There was annual training of not more than 28 days, and they wouldn’t be sent further than neighbouring counties unless invaded and then could be sent anywhere in Great Britain. Five regiments were raised for Wiltshire.

Substitution for the militia was allowed so, if your name was pulled out of the ballot, you could offer a substitute person assuming you could find someone. Interestingly some key Box figures were selected by the ballot including George Mullins, school master, and masons, Anthony Wilshire and Joseph Pillinger. They all found substitutes. William Butler junior also found a substitute and was listed in the 1803 census as lame.

The documents for Box end in 1808, but there are some fascinating posters from Devizes in 1814 that suggest hatred for Napoleon had not diminished. In June 1814 Napoleon had been caught and exiled to Elba and peace restored (or so the public thought). The people of Devizes celebrated by executing an image of Napoleon Bonaparte at the New Drop, Market Place, Devizes on Monday 18 April 1814 and distributing the last dying speech, confession and general details to those who attended.

Napoleon escaped from Elba, raised an army and met Wellington along with the British and Prussian troops at Waterloo in 1815 where he was finally vanquished. Its fascinating to think that Napoleon and the threat of his invasion could have had such an impact on the everyday lives of the inhabitants of Box.

At the start of the French Revolutionary Wars, the total size of the British Army was only 40,000 men which was gradually increased by 1815 to 250,000 servicemen, despite the huge number of fatalities especially in the Peninsula War after 1807. Originally the militia (who we nowadays call Reservists) were independent of the national standing army. They were selected by local ballot and paid for out of local rates, wore red uniforms, when called up, and, most importantly, they never served in their own county.

The invasion by Napoleon’s troops didn’t happen, but it still continued to be a threat for several more years resulting in more government requests for support. The Act of 29th June 1804 decreed a need for establishing and maintaining a permanent additional force for the defence of the realm and for the gradual reduction of the militia of England. In November 1804, Box had to raise a quota of three men for this permanent additional force or pay a £20 fine before 13 November 1804. John Parsons, James Garlick and Thomas Woodham were enlisted, and the Overseers got 1 guinea per man provided. However, a handwritten note explains that Thomas Woodham was discharged as deficient which might explain why a few weeks later Box was notified that it was short of one man and the Overseers had to produce him to the White Horse Inn, Chippenham, on Monday 12 November at 11 o’clock to be then enrolled to serve in the permanent additional force. They must have failed to do this as another handwritten note says that Mr Gisford, Box Overseer paid a twenty pounds fine as they were unable to supply the man.

The decisive naval victory for the British at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 saw the threat of invasion diminish somewhat but in 1808 when the Peninsular Campaign in Spain and Portugal began, the Government saw the need to enable a local militia force to be called forth and employed in case of invasion to aid His Majesty’s regular militia. Men between 18 and 30 selected by ballot enrolled for four-year period of service. There was annual training of not more than 28 days, and they wouldn’t be sent further than neighbouring counties unless invaded and then could be sent anywhere in Great Britain. Five regiments were raised for Wiltshire.

Substitution for the militia was allowed so, if your name was pulled out of the ballot, you could offer a substitute person assuming you could find someone. Interestingly some key Box figures were selected by the ballot including George Mullins, school master, and masons, Anthony Wilshire and Joseph Pillinger. They all found substitutes. William Butler junior also found a substitute and was listed in the 1803 census as lame.

The documents for Box end in 1808, but there are some fascinating posters from Devizes in 1814 that suggest hatred for Napoleon had not diminished. In June 1814 Napoleon had been caught and exiled to Elba and peace restored (or so the public thought). The people of Devizes celebrated by executing an image of Napoleon Bonaparte at the New Drop, Market Place, Devizes on Monday 18 April 1814 and distributing the last dying speech, confession and general details to those who attended.

Napoleon escaped from Elba, raised an army and met Wellington along with the British and Prussian troops at Waterloo in 1815 where he was finally vanquished. Its fascinating to think that Napoleon and the threat of his invasion could have had such an impact on the everyday lives of the inhabitants of Box.

References

[1] An inferior tradesman’s apology for adding his mite to the parochial contributions for the aid of government, 1 March 1798

[2] Letter from a True Briton from Litcham, Norfolk, 20 March 1798

[3] Letter from Mansion House, London to Rev Willis, Pickwick House, Corsham, 26 April 1798

[4] Matthew Humphreys was a wealthy Chippenham clothier who bought the house from the Northey family

[5] Letter from Lord Hobart, principal secretary of state to Lord Pembroke, 4 August 1803

[6] Thomas Hardy, The Trumpet-Major p.139-141

[7] Meeting notes of the Wiltshire Lieutenancy General Meeting, 19 November 1803

[1] An inferior tradesman’s apology for adding his mite to the parochial contributions for the aid of government, 1 March 1798

[2] Letter from a True Briton from Litcham, Norfolk, 20 March 1798

[3] Letter from Mansion House, London to Rev Willis, Pickwick House, Corsham, 26 April 1798

[4] Matthew Humphreys was a wealthy Chippenham clothier who bought the house from the Northey family

[5] Letter from Lord Hobart, principal secretary of state to Lord Pembroke, 4 August 1803

[6] Thomas Hardy, The Trumpet-Major p.139-141

[7] Meeting notes of the Wiltshire Lieutenancy General Meeting, 19 November 1803