Box’s Forgotten Tunnel: Middlehill Railway Tunnel Varian Tye September 2020

Middlehill tunnel was described by Hubert John Pragnell as the forgotten tunnel and to some extent this is still the case today.[1] People visiting Box often stop to admire the iconic portal of Box Tunnel at the viewing platform off the London Road, especially if a steam train is speeding through. However, if they looked west from London Road bridge, they would see another of Brunel’s wonders, the tunnel portal at Middlehill.

Of course, Box Tunnel is a magnificent piece of engineering, longest in the world at the time it was built, its significance rightly acknowledged. This article tries to highlight the importance of Middlehill Tunnel, another important heritage asset.

Of course, Box Tunnel is a magnificent piece of engineering, longest in the world at the time it was built, its significance rightly acknowledged. This article tries to highlight the importance of Middlehill Tunnel, another important heritage asset.

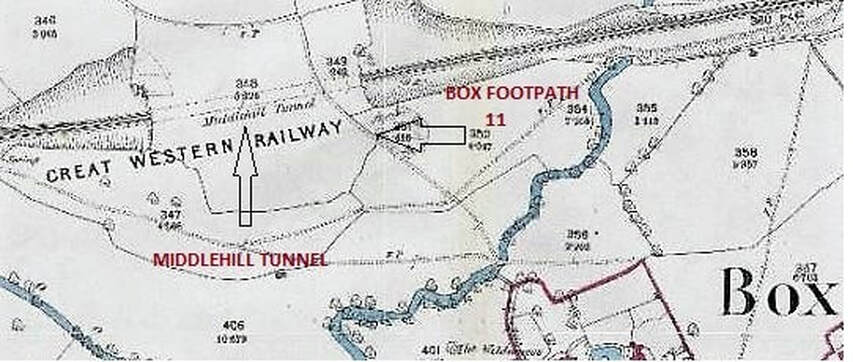

Location of Middlehill Tunnel. Historic OS map, 1844 -1888 (courtesy of Know Your Place). It is interesting to note on the above map the footpath that leads from Box out and over Middle Hill Tunnel as it is now designated a public right of way, Box Footpath 11. The importance of historic buildings and footpaths to The Parish of Box should not be underestimated.

Listed Building Description

The description of the Portals of Middlehill Tunnel on the Historic England website notes they are Grade II*, as is the West Portal to Box Tunnel [2] Compare this to the East Portal of Box Tunnel (in Corsham) which is only Grade II, its architectural interest described as austere.[3] In their assessment of the architectural and historic interest of the tunnel portals, Historic England have concluded that those in the parish of Box are of greater significance.

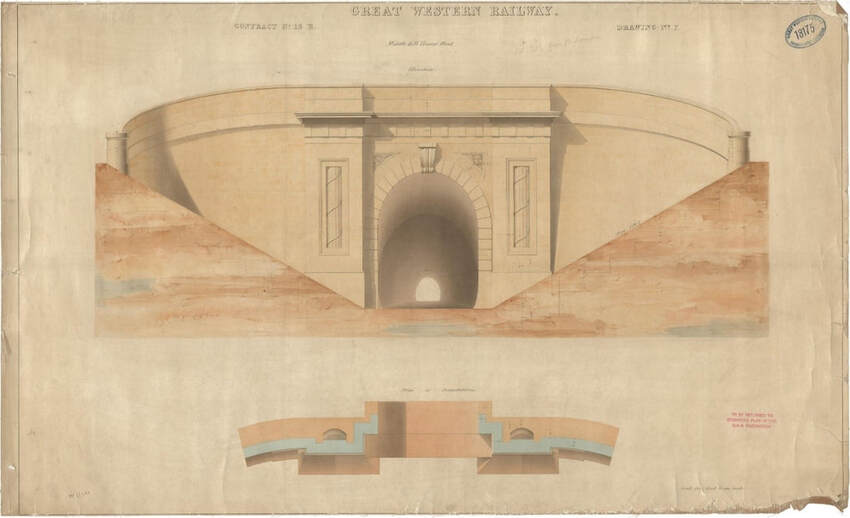

The list description of the East and West Portals of Middlehill Tunnel notes that they are identical. It states for both: Railway tunnel entrance, 1840 by IK Brunel for the Great Western Railway. Ashlar with some later refacing in brick. Ashlar classical archway flanked by curving retaining walls each side, refaced in brick, and terminated at circular piers. Main arch rusticated with heavy moulded console keystone and set back between piers each with recessed panel of massive fasces. Elemental Doric cornice, breaking forward over piers and ashlar parapet with moulded cornice.

The description of the Portals of Middlehill Tunnel on the Historic England website notes they are Grade II*, as is the West Portal to Box Tunnel [2] Compare this to the East Portal of Box Tunnel (in Corsham) which is only Grade II, its architectural interest described as austere.[3] In their assessment of the architectural and historic interest of the tunnel portals, Historic England have concluded that those in the parish of Box are of greater significance.

The list description of the East and West Portals of Middlehill Tunnel notes that they are identical. It states for both: Railway tunnel entrance, 1840 by IK Brunel for the Great Western Railway. Ashlar with some later refacing in brick. Ashlar classical archway flanked by curving retaining walls each side, refaced in brick, and terminated at circular piers. Main arch rusticated with heavy moulded console keystone and set back between piers each with recessed panel of massive fasces. Elemental Doric cornice, breaking forward over piers and ashlar parapet with moulded cornice.

The panels of fasces referred to are shown in the photograph above at either side of the main arch. They are an architectural feature derived from bundles of rods borne before high-ranking Roman Magistrates as a symbol of their power. Andrew Swift commented that If Brunel was aware of the derivation of the motif, he may have been indulging in a sophisticated joke.[4]

Architectural Beauty of the Tunnel

There have been several enthusiastic supporters of the architecture of Middlehill Tunnel. Andrew Swift describes the Middlehill to Box section of his railway trail as: the grand finale of the Brunel Trail, if you have only time to do one section, this is the one to do.[5] A report by Alan Baxter in 2012 notes: Like the nearby Box Tunnel, the identical Bath ashlar east and west portals of Middlehill Tunnel employ a monumental classical language in order to create picturesque landscape scene…architecturally one of the finest tunnel portals ever conceived in Britain and dating from the Pioneering phase of railway construction and very well preserved. The portals form part of a significant sequence of classical railway structure’s conceived as a picturesque landscape approach to Bath. This structure makes a significant contribution to the setting of the World Heritage Site.[6]

The tunnel portals in Box may, therefore, be viewed not only as of interest and importance in their own right but also having a group value when viewed together and read within the landscape. They may also be considered in their wider context as forming an impressive part of a larger group of other important Brunel listed railway structures on the GWR line. One view of the structures designed by Brunel on the Great Western Railway is that they were like a string of pearls on a necklace between Paddington and Bristol. I like to think that we are very fortunate to have three of the biggest and most important pearls on that necklace in the parish of Box.

Railway Cutting or Tunnel

When walking on Box Footpath 11, which leads from Box near the church and out and over Middlehill Tunnel, I have often pondered how short the tunnel is compared to the more famous Box Tunnel. Then I wondered if Brunel may have considered a railway cutting as opposed to a tunnel, such as the one he used at Sonning, Berkshire.

There have been several enthusiastic supporters of the architecture of Middlehill Tunnel. Andrew Swift describes the Middlehill to Box section of his railway trail as: the grand finale of the Brunel Trail, if you have only time to do one section, this is the one to do.[5] A report by Alan Baxter in 2012 notes: Like the nearby Box Tunnel, the identical Bath ashlar east and west portals of Middlehill Tunnel employ a monumental classical language in order to create picturesque landscape scene…architecturally one of the finest tunnel portals ever conceived in Britain and dating from the Pioneering phase of railway construction and very well preserved. The portals form part of a significant sequence of classical railway structure’s conceived as a picturesque landscape approach to Bath. This structure makes a significant contribution to the setting of the World Heritage Site.[6]

The tunnel portals in Box may, therefore, be viewed not only as of interest and importance in their own right but also having a group value when viewed together and read within the landscape. They may also be considered in their wider context as forming an impressive part of a larger group of other important Brunel listed railway structures on the GWR line. One view of the structures designed by Brunel on the Great Western Railway is that they were like a string of pearls on a necklace between Paddington and Bristol. I like to think that we are very fortunate to have three of the biggest and most important pearls on that necklace in the parish of Box.

Railway Cutting or Tunnel

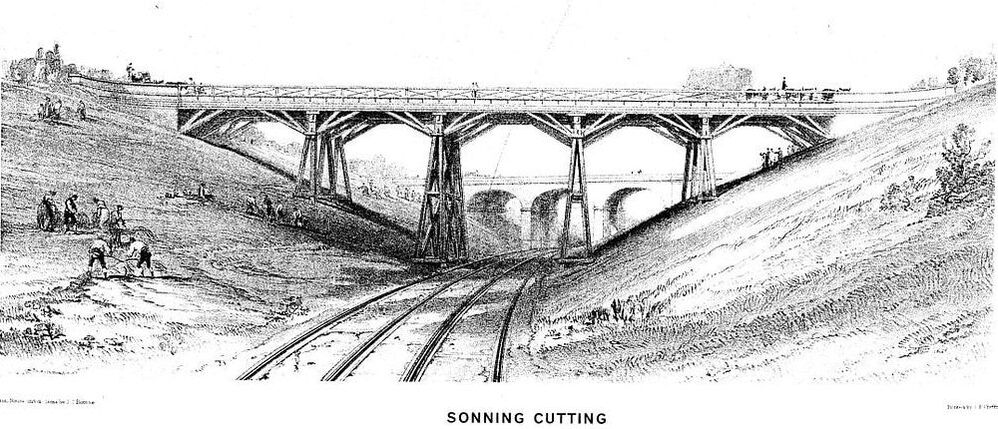

When walking on Box Footpath 11, which leads from Box near the church and out and over Middlehill Tunnel, I have often pondered how short the tunnel is compared to the more famous Box Tunnel. Then I wondered if Brunel may have considered a railway cutting as opposed to a tunnel, such as the one he used at Sonning, Berkshire.

JC Bourne's illustration of Sonning Railway cutting (courtesy of Wikipedia). Sonning cutting is on the GWR to the east of Reading station and to the west of Twyford station in the county of Berkshire. Brunel's original route had been around the north of Sonning Hill past the village but, because of local objections, the railway bypassed the village in a cutting.

Hubert Pragnell suggests that the tunnel was originally intended to be a cutting with a bridge across it. He states, “The clue may lie in a report by Brunel to the Directors on 17 October 1836, where he mentions a possible deviation in the Box valley depending on “an arrangement being made with Mr Wiltshire of Shockerwick”. The matter was still not resolved a year later when Brunel reported “that construction was seriously inconvenienced in consequence of the delay in Mr Wiltshire’s business. Nothing prevents the contract from Bathwick to Box Tunnel being ready but this.” This is the on-going argument which had surfaced at the House of Lords enquiry in 1835 with the family owning not only land through which the track would pass but also the “right to the view” as they saw it. Elizabeth Wiltshire farmed fields about a quarter of a mile to the west of the tunnel. The fact that there are no drawings for the portals in the sketchbooks, yet there are two drawings marked ‘Middle Hill Bridge’ in an 1838 sketchbook, suggests there was never an intention to have a tunnel at this point. As I have suggested in a previous chapter the tunnel was made purely to satisfy the Wiltshires, who wished to retain the view of the existing hill rather than a violent visual gash in the hillside. Better a Georgian style portal!

He goes on to say, In the Box Tithe map of December 1838, five members of the Wiltshire family (major haulage carriers in the 18th century) are listed as owning land in the vicinity of the proposed railway track. The family mansion of Shockerwick was however across the By Brook in Somerset.[7]

The speed and power of the railways took traffic away from Georgian hauliers and the carriage trade. It is perhaps not surprising that Brunel found it difficult to take his railway line across the Wiltshire family land and their magnificent mansion at Shockerwick. Perhaps economics as well as the view of the gash in the hillside at Middlehill would have raised concern in the family. The print below by Alan Fearnley shows a view of an old post coach crossing London Road Bridge, also designed by Brunel, with views of a steam train and the Box Tunnel portal in the distance. It is a timely and evocative reminder of the competition between the railways and horse-drawn hauliers and carriers at this time. Coach travellers looking from the bridge would have had a fine view of the East Portal of Middlehill Tunnel.

He goes on to say, In the Box Tithe map of December 1838, five members of the Wiltshire family (major haulage carriers in the 18th century) are listed as owning land in the vicinity of the proposed railway track. The family mansion of Shockerwick was however across the By Brook in Somerset.[7]

The speed and power of the railways took traffic away from Georgian hauliers and the carriage trade. It is perhaps not surprising that Brunel found it difficult to take his railway line across the Wiltshire family land and their magnificent mansion at Shockerwick. Perhaps economics as well as the view of the gash in the hillside at Middlehill would have raised concern in the family. The print below by Alan Fearnley shows a view of an old post coach crossing London Road Bridge, also designed by Brunel, with views of a steam train and the Box Tunnel portal in the distance. It is a timely and evocative reminder of the competition between the railways and horse-drawn hauliers and carriers at this time. Coach travellers looking from the bridge would have had a fine view of the East Portal of Middlehill Tunnel.

Why Has Middlehill Tunnel Been Overlooked and Why such Grand Portals?

Hubert Pragnell considered reasons why Middlehill Tunnel had been overlooked. He suggested that it could have been overlooked because it did not involve the labour and hardship needed to create nearby Box Tunnel and that Brunel was aware of the fact that a tunnel was unseen as far as passengers were concerned, whereas a viaduct, aqueduct or bridge could have an aesthetic place in the landscape. So, he designed the West Portals of Box Tunnel and both Portals of Middlehill Tunnel to be seen in the landscape and as a feature for travellers on the main Bath –London road, even if unseen from within a railway carriage.

Adrian Vaughan considered that the three Romanised Portals suitable for a Napoleonic figure such as Brunel - triumphal arches to mark his victory over nature and his rival, John Rennie the Elder, who had designed the magnificent Dundas Aqueduct, only a few miles away from Box.[8] I believe Brunel was also aware that he was approaching the historic city of Bath and wished to provide a fitting railway approach to it.

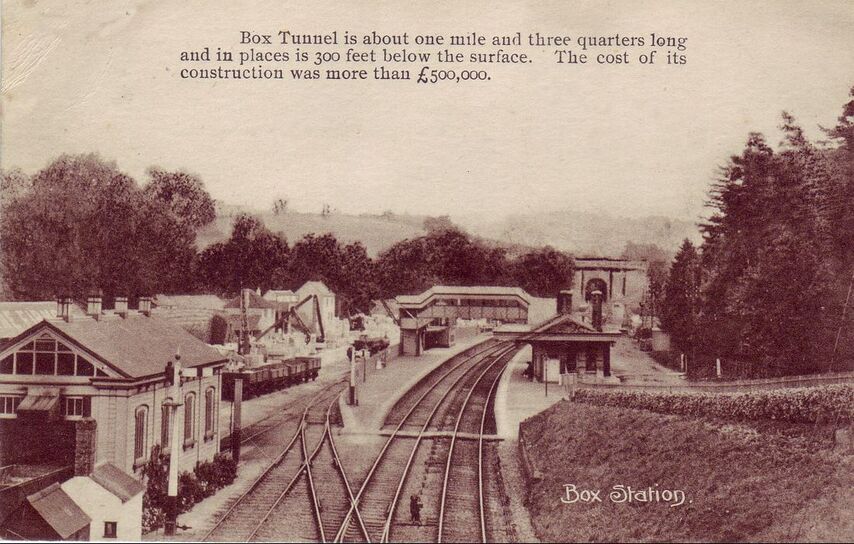

Although it may have been difficult to see the Middlehill Tunnel Portals from the train, it should not be forgotten that the first steam trains would have travelled much slower than today’s trains and that some of the carriages were open. The Western Portal of Middlehill Tunnel, its scale and magnificence, would probably have also been more readily appreciated in the context of views from Box Station, directly to the West of it, and when pulling out of the station and on the train travelling towards it.

Hubert Pragnell considered reasons why Middlehill Tunnel had been overlooked. He suggested that it could have been overlooked because it did not involve the labour and hardship needed to create nearby Box Tunnel and that Brunel was aware of the fact that a tunnel was unseen as far as passengers were concerned, whereas a viaduct, aqueduct or bridge could have an aesthetic place in the landscape. So, he designed the West Portals of Box Tunnel and both Portals of Middlehill Tunnel to be seen in the landscape and as a feature for travellers on the main Bath –London road, even if unseen from within a railway carriage.

Adrian Vaughan considered that the three Romanised Portals suitable for a Napoleonic figure such as Brunel - triumphal arches to mark his victory over nature and his rival, John Rennie the Elder, who had designed the magnificent Dundas Aqueduct, only a few miles away from Box.[8] I believe Brunel was also aware that he was approaching the historic city of Bath and wished to provide a fitting railway approach to it.

Although it may have been difficult to see the Middlehill Tunnel Portals from the train, it should not be forgotten that the first steam trains would have travelled much slower than today’s trains and that some of the carriages were open. The Western Portal of Middlehill Tunnel, its scale and magnificence, would probably have also been more readily appreciated in the context of views from Box Station, directly to the West of it, and when pulling out of the station and on the train travelling towards it.

Postcard courtesy Box Parish Council shows the proximity of the station to the West Portal of Middlehill Tunnel. The footbridge constructed in 1884 would no doubt have also supplied fine view of the tunnel’s portal. Regrettably, almost all of the historic buildings on this important site, including Brunel’s station, have been demolished.

Whilst walking over Middlehill Tunnel from Box I sometimes wonder if a cutting had been built what the gash in the hillside would have looked like. What would the final bridge design over the cutting been, what would the view from the bridge have been like? Andrew Swift states that one of the most splendid railway panoramas in the country is the view from Middlehill looking towards Box Tunnel.[9] Looking from a bridge that crossed a large gash in the hillside formed by a cutting towards Box Tunnel would have probably been memorable as well.

For my own part, I am thrilled that we ended up with three magnificent Tunnel Portals in the parish of Box without a cutting at Middlehill.

For my own part, I am thrilled that we ended up with three magnificent Tunnel Portals in the parish of Box without a cutting at Middlehill.

References

[1] Hubert John Pragnell, Early British Railway Tunnels, 2016, University of York Railway Studies

[2] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1022803

[3] Box Tunnel East Portal (MLN19912), Corsham - 1409161 | Historic England

[4] Andrew Swift, The Ringing Groves of Change, 2006, Akeman Press, p.283

[5] Andrew Swift, The Ringing Groves of Change, 2006, Akeman Press, p.283

[6] Alan Baxter, Great Western Main Line Route Structures Gazetteer Prepared for Network Rail, 2012, on line at: https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/gwml-gazetteer/

[7] See articles about Shockerwick House and the 1761 New Road

[8] Adrian Vaughan, Brunel as Creator of Environment in Conserving the Railway Heritage, 1997, Taylor & Francis Group

[9] Andrew Swift, The Ringing Groves of Change, 2006, Akeman Press, p.285

[1] Hubert John Pragnell, Early British Railway Tunnels, 2016, University of York Railway Studies

[2] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1022803

[3] Box Tunnel East Portal (MLN19912), Corsham - 1409161 | Historic England

[4] Andrew Swift, The Ringing Groves of Change, 2006, Akeman Press, p.283

[5] Andrew Swift, The Ringing Groves of Change, 2006, Akeman Press, p.283

[6] Alan Baxter, Great Western Main Line Route Structures Gazetteer Prepared for Network Rail, 2012, on line at: https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/gwml-gazetteer/

[7] See articles about Shockerwick House and the 1761 New Road

[8] Adrian Vaughan, Brunel as Creator of Environment in Conserving the Railway Heritage, 1997, Taylor & Francis Group

[9] Andrew Swift, The Ringing Groves of Change, 2006, Akeman Press, p.285