|

Horlock Family of Box and Marshfield

Brian Laurie-Beaumont Photos Brian Laurie-Beaumont, unless stated otherwise March 2017 I have researched the Horlock family (to whom I am related by marriage) and I may be able to add to articles written by David Ibberson, Charles John Sudell, and David Rawlings as pertains to the Horlock family, to whom I am grateful for introducing certain aspects of the family’s history and inter-family relationships. |

Our cousin, the late Henry Wimburn Sudell Sweetapple-Horlock, benefitted from an Oxford education but otherwise appears to have been a hard-working self-made man who was generous, though he had the apparent Horlock desire to live in style. I was asked by an executor of his estate to look into family connections to the portraits in Wimburn’s home. That required creating a family tree going back the three hundred years these paintings covered, and then follow all the family lines forward to the 20th century. What follows is a summary of that work and the hundreds of hours of both genealogical as well as historical research over the past two years.

Given so much discussion by others about the lifestyle of the Horlocks, I found it useful to occasionally provide financial details. So I think a word regarding the relative worth of money in the past comparative to today is required. I have used Measuring Worth, a free online conversion site, when making historic and present day comparisons. Strictly using inflation as a measurement undervalues money historically. With less money circulating in the past each pound’s value was actually greater than mere inflationary adjustment. How much more is a debated question. I have used the labour value / earnings as a comparative measure, this measures the amount of a person’s labour – at historic wages – it would take to buy a loaf of bread or a hat, or something else versus what people earn today. So while one pound sterling in 1800 based on inflation would be worth £73 today, in terms of a person’s labour earnings it is equivalent to £1,086. Another measurement would be income status – akin to one’s standard of living relative to others – that would make a pound worth £1,250 but I felt it was a bit less grounded in available statistics.

Family control of the vicarage at Box

Looking at the Clergy of England Database, 1540-1835, and linking it to the family genealogy, a person can see that a nearly continuous line of family relations were vicars at St Thomas à Becket for one hundred and sixty-five years. It began with

George Miller’s appointment as the vicar in 1707, he had been the curate since 1701; through his brother-in-law by a Webb marriage, John Morris (1740-1774); to a cousin Samuel Webb (1774-1797); to George’s grandson Isaac William Webb Horlock (1797-1830); and great-grandson Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock (1831-1872).

This may have been due to the existence of the advowson system, which goes back far into English history – possibly to Norman times and perhaps before. In return for setting aside a portion of his land and providing an endowment, a manor’s lord would be given the right to nominate the prelate for that church, though it required the bishop’s agreement. It meant he could influence what was preached at the pulpit. It also gave him the opportunity to employ a second son in both a potentially lucrative job as well as a position of social prestige greater than we often afford prelates today. Steps were taken in the 19th century to restrict the practice. The Benefices Act of 1898 and subsequent amendment in 1923 further reduced the use. Advowsons are very rare today and of only ceremonial use.

Given so much discussion by others about the lifestyle of the Horlocks, I found it useful to occasionally provide financial details. So I think a word regarding the relative worth of money in the past comparative to today is required. I have used Measuring Worth, a free online conversion site, when making historic and present day comparisons. Strictly using inflation as a measurement undervalues money historically. With less money circulating in the past each pound’s value was actually greater than mere inflationary adjustment. How much more is a debated question. I have used the labour value / earnings as a comparative measure, this measures the amount of a person’s labour – at historic wages – it would take to buy a loaf of bread or a hat, or something else versus what people earn today. So while one pound sterling in 1800 based on inflation would be worth £73 today, in terms of a person’s labour earnings it is equivalent to £1,086. Another measurement would be income status – akin to one’s standard of living relative to others – that would make a pound worth £1,250 but I felt it was a bit less grounded in available statistics.

Family control of the vicarage at Box

Looking at the Clergy of England Database, 1540-1835, and linking it to the family genealogy, a person can see that a nearly continuous line of family relations were vicars at St Thomas à Becket for one hundred and sixty-five years. It began with

George Miller’s appointment as the vicar in 1707, he had been the curate since 1701; through his brother-in-law by a Webb marriage, John Morris (1740-1774); to a cousin Samuel Webb (1774-1797); to George’s grandson Isaac William Webb Horlock (1797-1830); and great-grandson Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock (1831-1872).

This may have been due to the existence of the advowson system, which goes back far into English history – possibly to Norman times and perhaps before. In return for setting aside a portion of his land and providing an endowment, a manor’s lord would be given the right to nominate the prelate for that church, though it required the bishop’s agreement. It meant he could influence what was preached at the pulpit. It also gave him the opportunity to employ a second son in both a potentially lucrative job as well as a position of social prestige greater than we often afford prelates today. Steps were taken in the 19th century to restrict the practice. The Benefices Act of 1898 and subsequent amendment in 1923 further reduced the use. Advowsons are very rare today and of only ceremonial use.

|

Horlock family comes to Box

The Horlocks entered the history of Box through the marriage of Lucy Miller, daughter of George Miller (sometimes called Millard), [1] vicar of Box, and his wife, the heiress Susanna Webb of Ashwick Hall, Marshfield. George Miller graduated Oxford in 1700 and was appointed to the church at Box in 1707. The Miller family came from near Boxwell, Gloucestershire. George was the brother of Pancefort Miller, who inherited two large Jamaican plantations through his wife. Pancefort died in 1725 and his infant son in 1727. George was Pancefort's executor and was left 500 pounds for himself and 100 pounds for the Charity School, which George Miller had created in Box with the financial help of a couple of local individuals. Pancefort also left George half of one of his Jamaican plantations subject to the passing of Pancefort's mother-in-law, Frances Mitchell, and her son Thomas, who had the use of the plantation during their lives.[2] It is not certain he ever inherited his share as that will was contested and still had not been settled by 1770. |

George's will was probated on 10 May 1740 [4] although it was written in 1732 before his other two brothers, Thomas and William, had died as they are mentioned in his will. He left almost everything to his wife except 200 pounds to his daughter Lucy, a considerable amount for the day that today would equate to an inheritance of £385,000 - he wasn't poor. He died before his wife inherited Ashwick, so the money didn't come from that source. It may have derived from the inheritance from Pancefort Miller or even his father.

|

The Webb Inheritance

It has been mentioned it is curious that Susanna inherited the Webb fortune as she had two older sisters as well as a younger sister, married, with a son, a possible male heir. This can be explained by the family chronology. William Webb's will was written in 1716 and probated 17 March 1725.[5] It stipulated that whoever inherited his estate had to carry the Webb name. George Miller never incorporated the Webb name so that indicates his wife did not inherit in George’s lifetime. This suggests William Webb's eldest daughter would have inherited, as per his will. His oldest daughter was named Lucy (1681-1746). Land deeds previously in the possession of Wimburn Horlock note Lucy Webb, spinster, in both 1729 and 1735 as being of Ashwicke, Marshfield. She never married. His second daughter Elizabeth (1684-1700?), also unmarried, died before her father. Susanna (1688-1760) was next in line. |

Until a will is discovered for Lucy Webb, we will have to think she thought the next child of her father should receive the estate, as stated in her father’s will, regardless of whether they were married and whether they had a child or if it were male or female. After all, she was an unmarried female without child and had inherited from her father. The estate moved from the father's oldest child to the next living oldest child and thence to that person's only child, Lucy Miller. Susanna would have inherited after the passing of her sister Lucy (1746), after her husband died (1740) but before her daughter Lucy was married (1753).

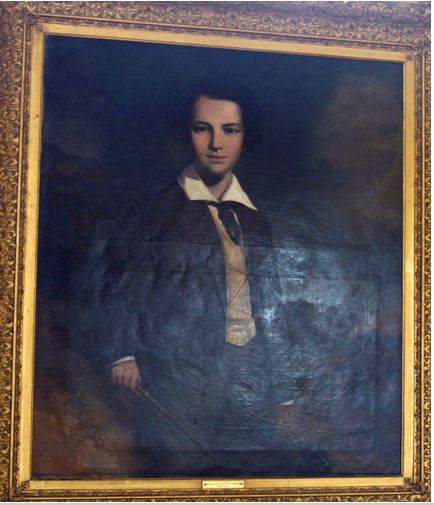

Lucy Miller married Isaac Horlock (1728-1821), the son of Benjamin Horlock of Trowbridge, in 1753. Although no marriage document has yet been found, the event was announced in a society paper of the time, The Gentleman’s Magazine, London. It was somewhat crassly stated in the June issue 1754: [June] 11, Isaac Horlock, of Trowbridge, Esq; [marriage] to Miss Miller, a £20,000 fortune.[6] That magazine had a habit of announcing when men had bagged a wealthy wife. On the same page another fellow had found himself a wife with £50,000. Whilst today we might consider Isaac Horlock a fortune hunter, marrying for romantic love was not the norm in past centuries. For Lucy Miller, Isaac was – based on his portrait – a handsome man from a well-to-do family, and probably having the requisite social manners. Still, with her fortune and at 22 not yet an old maid, Lucy could have had other suitors. That she chose Isaac Horlock may indicate she had an affection for him. More likely it was her mother who wanted to see her only child settled into a marriage; Susanna was already 65 when Lucy married, old for the time.

Lucy Miller married Isaac Horlock (1728-1821), the son of Benjamin Horlock of Trowbridge, in 1753. Although no marriage document has yet been found, the event was announced in a society paper of the time, The Gentleman’s Magazine, London. It was somewhat crassly stated in the June issue 1754: [June] 11, Isaac Horlock, of Trowbridge, Esq; [marriage] to Miss Miller, a £20,000 fortune.[6] That magazine had a habit of announcing when men had bagged a wealthy wife. On the same page another fellow had found himself a wife with £50,000. Whilst today we might consider Isaac Horlock a fortune hunter, marrying for romantic love was not the norm in past centuries. For Lucy Miller, Isaac was – based on his portrait – a handsome man from a well-to-do family, and probably having the requisite social manners. Still, with her fortune and at 22 not yet an old maid, Lucy could have had other suitors. That she chose Isaac Horlock may indicate she had an affection for him. More likely it was her mother who wanted to see her only child settled into a marriage; Susanna was already 65 when Lucy married, old for the time.

|

Isaac Webb Horlock (1728-1821)

Horlocks had been in Trowbridge since at least 1500. However, the Isaac Horlock of Ashwicke Hall – though related to the Trowbridge Horlocks - was from the Blandford Forum branch of the family. His father Benjamin Horlock (1700?-1731) was a clothier, whose father was also named Isaac. He was an apothecary, and a wealthy one at that. Among the many benefices in the elder Isaac’s will, he left £1,500 to Benjamin and another £500 to his grandson Isaac. £500 equates to an income of £920,000 today. Benjamin added to his son’s fortune in his own will, leaving him the residual of his estate after other gifts were deducted and after the death or marriage of his wife. The worth of the inheritance is unknown but Benjamin’s gifts to other family members were in the hundreds of pounds so the remainder was likely substantial. Left: Isaac Webb Horlock |

In 1718 Benjamin’s father paid to apprentice his son to William Temple, a clothier in Trowbidge. That brought him into contact with the local Mortimer family, also clothiers. On the same page noting Benjamin’s apprenticeship is that of John Mortimer, son of Sarah Mortimer, widowed in 1716. Benjamin ended up marrying Sarah Mortimer’s daughter, also called Sarah. Her father, John, had been a wealthy clothier. Just how wealthy is indicated by her brother Nathaniel Mortimer’s home, Beckington Castle (actually a mansion house). Sarah had a modest inheritance from her father.

So Isaac’s family was likely solidly upper middle-class by the standards of the day. And he was himself well off in his own right along with being a clothier in what was at the time a lucrative trade. He would have been regarded as a suitable spouse for a clergyman’s daughter. But this marriage brought with it Lucy’s fortune that was most likely a major step up for him socially.

It is uncertain whether the couple lived at Ashwicke Hall with Lucy’s mother. All the children were baptized at St. James Church, Trowbidge, as had generations of other Horlocks. Whether this was because the family lived at Trowbridge or simply due to Horlock tradition is unknown.

So Isaac’s family was likely solidly upper middle-class by the standards of the day. And he was himself well off in his own right along with being a clothier in what was at the time a lucrative trade. He would have been regarded as a suitable spouse for a clergyman’s daughter. But this marriage brought with it Lucy’s fortune that was most likely a major step up for him socially.

It is uncertain whether the couple lived at Ashwicke Hall with Lucy’s mother. All the children were baptized at St. James Church, Trowbidge, as had generations of other Horlocks. Whether this was because the family lived at Trowbridge or simply due to Horlock tradition is unknown.

|

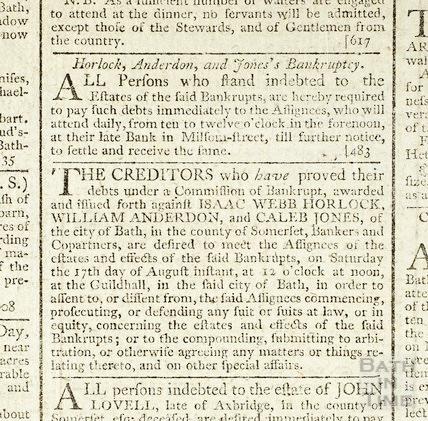

It can be assumed Isaac and family were at Ashwick Hall by 1760 after the death of his mother-in-law. The poll books put Isaac Webb Horlock at Ashwicke in 1776.[7] Lucy’s inheritance allowed him to be a founder of the Bath and Somerset Bank in Bristol, created in 1776, along with his cousin, Joseph Mortimer, and a few others. The late 18th century, with the expansion of British trade and industrialization, saw a rise in the economy. The good times however were not to last. The bank went bankrupt in Aug 1793, one of three banks in Bath to succumb, victims of a sudden devaluation of land and disruption of trade caused by the start of the wars with France. An investigation into one of the three banks (not Isaac’s) concluded the fault was mostly simply bad timing not bad management.[8] Much of Isaac Horlock’s property appears to have been sold to settle his debts.[9]

Right: Notice of asset sale (courtesy Bath in Time) |

That though was not the end of Isaac Horlock. Despite the announcement of land sales, the family must have found a way to hold onto both Ashwick Hall and The Rocks as these properties passed onto their son Isaac William Webb Horlock [10] and are referenced as the homes of his two oldest sons. It is not known exactly when the 1,000 acre neighbouring property, called

The Rocks, actually came into Isaac’s possession. The previous owner’s family line had come to an end and there was no-one else to bequeath it. Perhaps it was inherited. Or possibly The Rocks may have come to him due to his having acquired an interest in the estate much earlier. The 1775 tax records show him paying taxes (nearly £20 – easily one of the highest land tax in the area) on a portion of The Rocks (as well as tax payments on several other properties held by others – perhaps these properties were mortgaged to him, maybe through his bank).[11]

Despite the financial losses Isaac maintained his social standing. In 1811 he was the magistrate in Marshfield, so undoubtedly Isaac still had important friends.[12] Isaac Horlock died at Ashwicke Hall 7 November 1821.[13] Lucy Miller died in either 1773 or 1777, as the National Burial Index for England and Wales has two entries for the burial of Lucy Horlock at St Thomas à Becket for those years but does not distinguish mother from daughter.

The Rocks, actually came into Isaac’s possession. The previous owner’s family line had come to an end and there was no-one else to bequeath it. Perhaps it was inherited. Or possibly The Rocks may have come to him due to his having acquired an interest in the estate much earlier. The 1775 tax records show him paying taxes (nearly £20 – easily one of the highest land tax in the area) on a portion of The Rocks (as well as tax payments on several other properties held by others – perhaps these properties were mortgaged to him, maybe through his bank).[11]

Despite the financial losses Isaac maintained his social standing. In 1811 he was the magistrate in Marshfield, so undoubtedly Isaac still had important friends.[12] Isaac Horlock died at Ashwicke Hall 7 November 1821.[13] Lucy Miller died in either 1773 or 1777, as the National Burial Index for England and Wales has two entries for the burial of Lucy Horlock at St Thomas à Becket for those years but does not distinguish mother from daughter.

|

Isaac Horlock and the slave trade

It has been stated he was a slave trader, perhaps based on stories of the vicarage at some point secreting slaves. However, I have yet to see documentation to support the assertion. I suspect there may be some confusion with the activities of families related to the Horlocks through marriage. As already noted, Isaac’s father-in-law, George Miller, had a brother, Pancefort, who certainly owned slaves. Slavery was only abolished in Britain in 1833. Could Pancefort Miller have brought slaves with him to Box? Left: Box House built by the Horlocks (courtesy Carol Payne) |

Also, Isaac’s grandson, Isaac John Webb Horlock, married the daughter of Andreas Christian Boode who owned five plantations in Demerara (a South American Dutch colony). Maybe a black person showed up in Box due to that connection? There is a document in the Slave Registers of former British Colonial Dependencies, 1813-1834, which records the ownership of slaves by Thomas William Horlock, but he is not connected to these Horlocks. I have never seen evidence that Horlocks of Box were themselves involved with slavery. They did employ a black servant from Jamaica but there is no evidence he was a slave.

Morris family connection

Another profile on the Box Peoples website notes a connection between the Horlocks and a notable local family named Morris.

A Land Tax Redemption record from 1798 shows John Morris renting a property in Box from Isaac Webb Horlock. Also, Wimburn Sweetapple-Horlock had a painting in his possession titled Councillor [sic] John Morris (1735-1814), almost certainly the solicitor named in Mr Rawlings' article.

Morris family connection

Another profile on the Box Peoples website notes a connection between the Horlocks and a notable local family named Morris.

A Land Tax Redemption record from 1798 shows John Morris renting a property in Box from Isaac Webb Horlock. Also, Wimburn Sweetapple-Horlock had a painting in his possession titled Councillor [sic] John Morris (1735-1814), almost certainly the solicitor named in Mr Rawlings' article.

Children of Isaac Horlock and Lucy Miller

Isaac Horlock and Lucy Miller had seven children between 1754 and 1773. George (b 1757) died in 1765 and they had a second son named George baptized in the following year. As noted already, all were baptized at St James Church, Trowbridge. In only one baptism record, that of Susanna Jemima (b 1770), was the father noted as Isaac Webb Horlock.[14] However, they did give their second child and first son born in 1756, the name William Webb Horlock.[15] Although they had not inherited Ashwick Hall by then (Lucy's mother only died in 1760), Isaac probably took on the Webb surname to underline that he and his wife were the next in line for that estate and were abiding by William Webb's will stipulation.

There were four girls. Their first child was a daughter, Lucy, born in 1755 and died, as per the above note, in 1773 or 1777, unmarried. The third child and second daughter was Maria Charlotte, born in 1761. She married John Wilkinson Denison, 5 March 1787. Their daughter, Lucy Maria Charlotte Denison, married Charles Manners-Sutton, Viscount Canterbury, 8 July 1811, the son of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Susanna Jemima was their fifth child and third daughter, born in 1770. She married John Hicks on 11 October 1809 at Box and had two daughters. She died at her home, Plomer Hill House, in Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, but was buried in Box in April 1845. Susanna had a reasonably large estate, spreading it among her step-daughters, nephews and nieces, friends, and was notably generous to her servants.[16] Several people received life-time annuities of a pound per week, including her two longest serving servants. In her will she left her horses and carriage that took her body to the graveyard to her nephew, Rev Holled Horlock. Indeed the reverend received the largest bequest from her estate, £400. Holled’s brothers, Isaac John Horlock and William Knightley Horlock received but £100 as they were otherwise, as their aunt noted, amply provided for, that is each had inherited one of their parent’s landed estates. Isaac and Lucy’s last daughter and final child was named Sarah, who was born in 1773. Nothing more has been discovered about her.

As noted above, of their three sons one, George, died as a young child. Nothing is known of the second George. Susanna did not mention any of her brothers in her will written in January 1741. It is known her brother Isaac was dead by the end of November 1829. Given so many relatives were mentioned in the will any living brother could be expected to be included, so presumably the second George was also dead before 1841. As other nieces and nephews mentioned in the will are accounted for in relation to their parents, it is further presumed the latter George died without issue and may not even have married. That leaves the couple’s only surviving son, Isaac.

Isaac Horlock and Lucy Miller had seven children between 1754 and 1773. George (b 1757) died in 1765 and they had a second son named George baptized in the following year. As noted already, all were baptized at St James Church, Trowbridge. In only one baptism record, that of Susanna Jemima (b 1770), was the father noted as Isaac Webb Horlock.[14] However, they did give their second child and first son born in 1756, the name William Webb Horlock.[15] Although they had not inherited Ashwick Hall by then (Lucy's mother only died in 1760), Isaac probably took on the Webb surname to underline that he and his wife were the next in line for that estate and were abiding by William Webb's will stipulation.

There were four girls. Their first child was a daughter, Lucy, born in 1755 and died, as per the above note, in 1773 or 1777, unmarried. The third child and second daughter was Maria Charlotte, born in 1761. She married John Wilkinson Denison, 5 March 1787. Their daughter, Lucy Maria Charlotte Denison, married Charles Manners-Sutton, Viscount Canterbury, 8 July 1811, the son of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Susanna Jemima was their fifth child and third daughter, born in 1770. She married John Hicks on 11 October 1809 at Box and had two daughters. She died at her home, Plomer Hill House, in Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, but was buried in Box in April 1845. Susanna had a reasonably large estate, spreading it among her step-daughters, nephews and nieces, friends, and was notably generous to her servants.[16] Several people received life-time annuities of a pound per week, including her two longest serving servants. In her will she left her horses and carriage that took her body to the graveyard to her nephew, Rev Holled Horlock. Indeed the reverend received the largest bequest from her estate, £400. Holled’s brothers, Isaac John Horlock and William Knightley Horlock received but £100 as they were otherwise, as their aunt noted, amply provided for, that is each had inherited one of their parent’s landed estates. Isaac and Lucy’s last daughter and final child was named Sarah, who was born in 1773. Nothing more has been discovered about her.

As noted above, of their three sons one, George, died as a young child. Nothing is known of the second George. Susanna did not mention any of her brothers in her will written in January 1741. It is known her brother Isaac was dead by the end of November 1829. Given so many relatives were mentioned in the will any living brother could be expected to be included, so presumably the second George was also dead before 1841. As other nieces and nephews mentioned in the will are accounted for in relation to their parents, it is further presumed the latter George died without issue and may not even have married. That leaves the couple’s only surviving son, Isaac.

|

Rev Isaac William Webb Horlock (1756-1829)

Isaac William Webb was the Horlock’s second child and first son. He inherited The Rocks as well as Ashwicke Hall. He was born at Trowbridge in December 1756, matriculated Oxford University (Brasenose College) on 28 June 1776, received his master’s degree on 29 March 1781, and was assigned as rector of Wynford, Gloucestershire, in 1797. He was assigned as vicar at Box in 1799 and also became the domestic chaplain to Robert, Hobart, the fourth Earl of Buckingham.[17 and 18] The latter is important as one of the perks of being a domestic chaplain to either a monarch or high noble was the right to purchase a license for a second benefice or posting. So it would appear Isaac came to Box because his father held the advowson – a right that went with ownership of the principle local manor, in this case Ashwicke Hall. And Isaac could purchase a license to hold a second post at another church (Wynford) without having to reside there, thus increasing his income. By holding two church posts along with being a private chaplain to a noble family one can begin to see where some of his money came from prior to inheriting Ashwicke Hall or marrying – and why he would be a good match for somebody’s daughter. |

Isaac William Webb Horlock married Ann Smith from Leicestershire. No record of the event has been found but it would have been about 1799, based on when Isaac graduated (1797) and when their first child was born (1801). Ann was thirty-five by then and one presumes happy at the proposal of marriage. Before we call this Isaac a fortune hunter as well, remember he was forty-three himself, already had a good income and so was as likely to be looking for a woman near his age to live out the rest of his life with as well as young enough to bear him a child to succeed to the large estate he would one day inherit. Her father

Holled Smith had been a successful attorney. The family lived at Normanton Turvill, a large estate in Leicestershire, until her father died in 1795. The estate was then sold to Richard Arkwright, inventor of the spinning frame, for £33,000, which suggests the wealth of the Smith family. Holled Smith’s wife predeceased him so his children would have inherited immediately. But Anne is not mentioned specifically in her father’s will, probated in 1796.[19] It appears Holled Smith left some of his daughters annuities of £130 a year. Presumably Anne received something similar, nice but not quite the riches some allude to.

Isaac served as vicar from 1799 until his death in 1830, being succeeded by his son. The couple had three sons.

Isaac John Webb Horlock (1801- 1875)

Isaac John Webb Horlock (b 1801) matriculated Queens College, Oxford 15 June 1819, and received his Bachelor of Arts in 1824, by which time he had inherited The Rocks.[20] In April 1826 he married Phoebe Boode, daughter of Andreas Christian Boode, owner of five sugar plantations in Demerara, South America, and hence a very wealthy man. The marriage, however, did not last. They divorced in May 1834.[21] She went on to remarry while he fell into financial decline – in part, it is said, after losing a legal battle related to his divorce. By 1853, it has been alleged, he had defaulted on his mortgage. In the 1871 census he is found at Wixley Hall in Yorkshire, listed as a widower - rather than a divorcee, though Phoebe’s death date is indeed unknown – living on a pension.[22] Wixley Hall is described by British Listed Buildings as an almshouse since 1754 for decayed gentlemen.

However, he was buried back at Marshfield.

He was survived by a daughter, Anna Phoebe, who married the son of Catharina Elizabeth Adelaide Boode, (a cousin?) and two sons: Frederick Geldart Webb Horlock (who married Emily and then Isabella St John and, through his daughter Elizabeth, from the second marriage, lives on today through the Radcliffe family); and, Knightley Lionel Horlock, who died young.

Knightly William Webb Horlock (1802 – 1882)

Knightly William Webb Horlock married Mary Ann Dacre Brooke Maxwell (1805-1883) on 15 April 1826. Despite the elaborate middle names it has not been able to tease her background out of all the Mary Ann Maxwells alive at the time. In the 1841 census Knightley was found at Ashwicke Hall, with his nine servants. By the 1851 census he was down to two, even though he did earn an income as a magistrate and the fact he was a published author of at least ten books (some on the care and training of fox hounds and horses, some fictional stories of a country gentleman’s life under the pseudonym Scrutator.[23] He spent a month in the county jail during the spring of 1849 for an unpaid debt, [24] which may have something to do with selling Ashwick Hall later that year (the 18th century hall was later demolished by the new owner) [Historic England: Ashwicke Hall]. He was not destitute though. The census for 1881 notes he was receiving an annuity. They had two children.

His daughter Georgina Lucy Mary Horlock married William Charles Burman and led a financially comfortable life, despite her father’s misfortunes, and the greater problems her brother had. Her husband predeceased her (1870) and it looks like she spent her last few years living with her parents at Avon Bank Cottage, Winkton, Hampshire.[25] The couple appear not to have had children. So it is presumed that when Georgina dies (1876) she left her estate (under £4,000) to her parents.[26] That is interesting as when her mother passed away in 1883 she left but £266 – which was taken by her solicitor against her debt to him.[27]

His son, Maxwell Horlock, would likely be considered the family black sheep. Maxwell started out with a good education, being found in the 1851 census at school in Bruton, Somerset, likely Kings Bruton. Sometime things went awry. He was imprisoned at least three times, all for false pretense: first on 20 February 1860, when he received three months imprisonment; next, on

11 April 1870, when he received two years imprisonment (served in Nottingham, according to the 1871 census) and seven years probation; and then, on 5 January 1874, with seven years penal servitude (hard labour) and seven years probation. He finished up in Winchester, being sentenced for obtaining money under false pretense and fraud, and on 7 April 1884 he was sentenced to two years penal servitude and three years probation.[5] Hard labour would have been quite an experience for somebody brought up in a more genteel lifestyle. Still, it could have been worse because prior to the 1853 Penal Servitude Act he would have been transported when he received a seven year term.[28]

Maxwell Horlock married Elizabeth Fripp at Southampton on 13 November 1853 [29] but does not show up in the 1861 and 1881 census, although we know he was still alive. He may have been missed within the prison population. There is no indication that he had children.

Rev Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock (1807-1901)

The Rev Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock graduated from Magdelen Hall, Hereford College, Oxford University; was made an assistant stipendiary curate to Box in October 1830 (just as his father was dying); was ordained 27 March 1831, and made the vicar at Box the following day.[30] He lived well. He had five servants in the 1851 and 1861 census while adding a sixth in 1871. In the 1881 census Holled still had three servants and two in 1891 and 1901, when no longer an active vicar so probably in less need of servants.

There has been some wonderment as to how he could afford to do so. First, he had income from being a vicar. In the 1861 census Holled's neighbour, also a clergyman with six daughters and no parish, employed three servants. Next, his father left him a half-interest in Ashwicke Hall, the division of such income from the estate may have doomed his brother Knightley William Horlock to lose Ashwicke. Maybe profits from his writings, such as An Exposition of the Parables, helped Holled's finances. And then, there was the inheritance from his aunt in 1841. Finally, he too married well.

Holled Smith had been a successful attorney. The family lived at Normanton Turvill, a large estate in Leicestershire, until her father died in 1795. The estate was then sold to Richard Arkwright, inventor of the spinning frame, for £33,000, which suggests the wealth of the Smith family. Holled Smith’s wife predeceased him so his children would have inherited immediately. But Anne is not mentioned specifically in her father’s will, probated in 1796.[19] It appears Holled Smith left some of his daughters annuities of £130 a year. Presumably Anne received something similar, nice but not quite the riches some allude to.

Isaac served as vicar from 1799 until his death in 1830, being succeeded by his son. The couple had three sons.

Isaac John Webb Horlock (1801- 1875)

Isaac John Webb Horlock (b 1801) matriculated Queens College, Oxford 15 June 1819, and received his Bachelor of Arts in 1824, by which time he had inherited The Rocks.[20] In April 1826 he married Phoebe Boode, daughter of Andreas Christian Boode, owner of five sugar plantations in Demerara, South America, and hence a very wealthy man. The marriage, however, did not last. They divorced in May 1834.[21] She went on to remarry while he fell into financial decline – in part, it is said, after losing a legal battle related to his divorce. By 1853, it has been alleged, he had defaulted on his mortgage. In the 1871 census he is found at Wixley Hall in Yorkshire, listed as a widower - rather than a divorcee, though Phoebe’s death date is indeed unknown – living on a pension.[22] Wixley Hall is described by British Listed Buildings as an almshouse since 1754 for decayed gentlemen.

However, he was buried back at Marshfield.

He was survived by a daughter, Anna Phoebe, who married the son of Catharina Elizabeth Adelaide Boode, (a cousin?) and two sons: Frederick Geldart Webb Horlock (who married Emily and then Isabella St John and, through his daughter Elizabeth, from the second marriage, lives on today through the Radcliffe family); and, Knightley Lionel Horlock, who died young.

Knightly William Webb Horlock (1802 – 1882)

Knightly William Webb Horlock married Mary Ann Dacre Brooke Maxwell (1805-1883) on 15 April 1826. Despite the elaborate middle names it has not been able to tease her background out of all the Mary Ann Maxwells alive at the time. In the 1841 census Knightley was found at Ashwicke Hall, with his nine servants. By the 1851 census he was down to two, even though he did earn an income as a magistrate and the fact he was a published author of at least ten books (some on the care and training of fox hounds and horses, some fictional stories of a country gentleman’s life under the pseudonym Scrutator.[23] He spent a month in the county jail during the spring of 1849 for an unpaid debt, [24] which may have something to do with selling Ashwick Hall later that year (the 18th century hall was later demolished by the new owner) [Historic England: Ashwicke Hall]. He was not destitute though. The census for 1881 notes he was receiving an annuity. They had two children.

His daughter Georgina Lucy Mary Horlock married William Charles Burman and led a financially comfortable life, despite her father’s misfortunes, and the greater problems her brother had. Her husband predeceased her (1870) and it looks like she spent her last few years living with her parents at Avon Bank Cottage, Winkton, Hampshire.[25] The couple appear not to have had children. So it is presumed that when Georgina dies (1876) she left her estate (under £4,000) to her parents.[26] That is interesting as when her mother passed away in 1883 she left but £266 – which was taken by her solicitor against her debt to him.[27]

His son, Maxwell Horlock, would likely be considered the family black sheep. Maxwell started out with a good education, being found in the 1851 census at school in Bruton, Somerset, likely Kings Bruton. Sometime things went awry. He was imprisoned at least three times, all for false pretense: first on 20 February 1860, when he received three months imprisonment; next, on

11 April 1870, when he received two years imprisonment (served in Nottingham, according to the 1871 census) and seven years probation; and then, on 5 January 1874, with seven years penal servitude (hard labour) and seven years probation. He finished up in Winchester, being sentenced for obtaining money under false pretense and fraud, and on 7 April 1884 he was sentenced to two years penal servitude and three years probation.[5] Hard labour would have been quite an experience for somebody brought up in a more genteel lifestyle. Still, it could have been worse because prior to the 1853 Penal Servitude Act he would have been transported when he received a seven year term.[28]

Maxwell Horlock married Elizabeth Fripp at Southampton on 13 November 1853 [29] but does not show up in the 1861 and 1881 census, although we know he was still alive. He may have been missed within the prison population. There is no indication that he had children.

Rev Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock (1807-1901)

The Rev Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock graduated from Magdelen Hall, Hereford College, Oxford University; was made an assistant stipendiary curate to Box in October 1830 (just as his father was dying); was ordained 27 March 1831, and made the vicar at Box the following day.[30] He lived well. He had five servants in the 1851 and 1861 census while adding a sixth in 1871. In the 1881 census Holled still had three servants and two in 1891 and 1901, when no longer an active vicar so probably in less need of servants.

There has been some wonderment as to how he could afford to do so. First, he had income from being a vicar. In the 1861 census Holled's neighbour, also a clergyman with six daughters and no parish, employed three servants. Next, his father left him a half-interest in Ashwicke Hall, the division of such income from the estate may have doomed his brother Knightley William Horlock to lose Ashwicke. Maybe profits from his writings, such as An Exposition of the Parables, helped Holled's finances. And then, there was the inheritance from his aunt in 1841. Finally, he too married well.

On 21 September 1832 he married Elizabeth Sudell (1807-1858). There is a description of the Sudell family of Blackburn, Lancashire, in the parish history published in 1877, taking the family back to 1600. It describes Elizabeth’s father, Henry Sudell (1764-1856) as a cloth merchant and manufacturer as well as a major landowner. It is said in 1820 he was a millionaire. Going through various histories about the area that reference Henry Sudell he seems to have been generous with the locals concerning public projects, charities, and his workers, at least by the standards of the time. By 1827 he had lost much of his fortune through overseas speculation. Most of his property, including their home Wofford Hall and much of the park, was settled upon Mr Sudell’s children.[31] The balance of the property (842 acres appraised at £60,000) was sold to settle his debts, though that sum seems inadequate to the total debts suggested elsewhere, so other assets were likely sold, such as business premises in town or other investments. Wofford Hall and the surrounding lands were sold by the family about 1831. It is unknown what was realised from the 1831 sale but the hall and property still made for a large estate. However, nothing in these descriptions suggest a man who stole away in the night leaving his creditors in the lurch.

Elizabeth remained in England with her husband but the rest of the family appears to have left for France, where Henry’s daughter Lydia died. The family returned to Ashley House, Box before 1848 as Henry’s wife died there in April that year.

Henry and his sons, Henry and Thomas, appear in the 1851 census for Box. All three were referenced as fundholders, that is each claimed to be financially self-sufficient investors. They employed five servants. Henry’s other daughter Alice lived nearby at

The Hermitage, next door to the vicarage. She also is noted as being of independent means but makes do with just two servants.

Her nephew Darrell was also at the Hermitage, but whether he is actually living there or just happens to be there during the census is an open question. Elizabeth was next door with her husband and daughter, Elizabeth, along with five servants.

Before the end of the decade all the Sudells were dead. And therein lies an inferred scandal.

Henry and his sons, Henry and Thomas, appear in the 1851 census for Box. All three were referenced as fundholders, that is each claimed to be financially self-sufficient investors. They employed five servants. Henry’s other daughter Alice lived nearby at

The Hermitage, next door to the vicarage. She also is noted as being of independent means but makes do with just two servants.

Her nephew Darrell was also at the Hermitage, but whether he is actually living there or just happens to be there during the census is an open question. Elizabeth was next door with her husband and daughter, Elizabeth, along with five servants.

Before the end of the decade all the Sudells were dead. And therein lies an inferred scandal.

The scandal

No doubt the rapid succession of Sudell deaths caused a stir. Henry junior died in 1851. The story goes he was bitten by a dog and struck by a stick (or cane) of the owner. He thereafter died, either by infection or poison depends on one’s interest in conspiracy theories. Henry senior died in 1856, age 92, which would be considered pretty old for those days or even today.

And Thomas died in 1857, age 54, actually close to an average age for the time. The sudden deaths of the sisters within days of each other in January 1858, wife and sister-in-law of Rev HDCS Horlock, got some people wondering. The Victorians liked a good story as much as anybody.

Various theories are offered up for the death of the two women: they ate tainted food, by accident or by malicious intent; they drank contaminated water, not a stretch in those days; breathing the unhealthy night air from the nearby graveyard; they were murdered for their money by the vicar, or the gardener for some unknown reason, or by people seeking revenge upon the Sudell family for the 1827 family financial turmoil (although these events are 30 years apart).

There is a back-story to these latter deaths that aided in making the last two deaths more salacious. There had been somebody two years prior writing letters to townsfolk condemning the Sudells and Rev Horlock and threatening death. One person was tried but acquitted. And Alice’s house had been burglarised a few weeks before her death. The family evidently did have at least one enemy. But they would have needed an accomplice within the household to use suspected poison, and who wishes to do away with their employer which leads one’s own unemployment.

There has been the suggestion the high-living reverend may have murdered the sisters to acquire their estates to fund his lifestyle. The problem with this suggestion is simply that Horlock would already control his wife’s money. Also, wills for both Thomas Sudell [32] and his sister Alice [33] left all their inheritance to their Horlock niece and nephew, including their railway stock.[34] By 1858 both were over twenty-one and thus would inherit directly, that is Rev Horlock would receive no money even to manage. As his wife was her siblings executor it is reasonable to expect the reverend knew the contents of the wills. Any idea he may have wanted his wife out of the way to remarry another wealthy woman is undermined by the fact he did not remarry until five years later; and his bride, Charlotte Butler Clarke, seems not to come from an especially wealthy family.

The deaths were covered by newspapers throughout the United Kingdom. The investigation put the cause down to contamination from the house water supply, potentially from bacteria from the nearby graveyard. My discussion of the few known facts of the case with a surgeon who has some knowledge of 19th century medicine and the poisons available at the time noted the available poisons would act far more quickly than taking a week to do in Elizabeth Sudell. The lingering nature of the illness suffered by the two women, along with the fact the servants sickened but recovered fairly quickly, led her to agree with the doctors at the time: cause of death was most likely due to bacteria acquired from water contamination.

As noted, Rev Horlock did remarry, in 1863. They had one child, who died many years after her parents, unmarried. He still had some assets to sustain himself. The land tax records in 1873 shows him owning 554 acres at Box worth nearly £1,000, from which he probably received rent on top of his vicar’s salary. The reverend remained at Box until 1878 when he became the vicar at Newton Poppleford, Devon.[35] He died there 28 December 1901, leaving his last daughter less than £80.[36]

No doubt the rapid succession of Sudell deaths caused a stir. Henry junior died in 1851. The story goes he was bitten by a dog and struck by a stick (or cane) of the owner. He thereafter died, either by infection or poison depends on one’s interest in conspiracy theories. Henry senior died in 1856, age 92, which would be considered pretty old for those days or even today.

And Thomas died in 1857, age 54, actually close to an average age for the time. The sudden deaths of the sisters within days of each other in January 1858, wife and sister-in-law of Rev HDCS Horlock, got some people wondering. The Victorians liked a good story as much as anybody.

Various theories are offered up for the death of the two women: they ate tainted food, by accident or by malicious intent; they drank contaminated water, not a stretch in those days; breathing the unhealthy night air from the nearby graveyard; they were murdered for their money by the vicar, or the gardener for some unknown reason, or by people seeking revenge upon the Sudell family for the 1827 family financial turmoil (although these events are 30 years apart).

There is a back-story to these latter deaths that aided in making the last two deaths more salacious. There had been somebody two years prior writing letters to townsfolk condemning the Sudells and Rev Horlock and threatening death. One person was tried but acquitted. And Alice’s house had been burglarised a few weeks before her death. The family evidently did have at least one enemy. But they would have needed an accomplice within the household to use suspected poison, and who wishes to do away with their employer which leads one’s own unemployment.

There has been the suggestion the high-living reverend may have murdered the sisters to acquire their estates to fund his lifestyle. The problem with this suggestion is simply that Horlock would already control his wife’s money. Also, wills for both Thomas Sudell [32] and his sister Alice [33] left all their inheritance to their Horlock niece and nephew, including their railway stock.[34] By 1858 both were over twenty-one and thus would inherit directly, that is Rev Horlock would receive no money even to manage. As his wife was her siblings executor it is reasonable to expect the reverend knew the contents of the wills. Any idea he may have wanted his wife out of the way to remarry another wealthy woman is undermined by the fact he did not remarry until five years later; and his bride, Charlotte Butler Clarke, seems not to come from an especially wealthy family.

The deaths were covered by newspapers throughout the United Kingdom. The investigation put the cause down to contamination from the house water supply, potentially from bacteria from the nearby graveyard. My discussion of the few known facts of the case with a surgeon who has some knowledge of 19th century medicine and the poisons available at the time noted the available poisons would act far more quickly than taking a week to do in Elizabeth Sudell. The lingering nature of the illness suffered by the two women, along with the fact the servants sickened but recovered fairly quickly, led her to agree with the doctors at the time: cause of death was most likely due to bacteria acquired from water contamination.

As noted, Rev Horlock did remarry, in 1863. They had one child, who died many years after her parents, unmarried. He still had some assets to sustain himself. The land tax records in 1873 shows him owning 554 acres at Box worth nearly £1,000, from which he probably received rent on top of his vicar’s salary. The reverend remained at Box until 1878 when he became the vicar at Newton Poppleford, Devon.[35] He died there 28 December 1901, leaving his last daughter less than £80.[36]

|

Rev Darrell Holled Webb Horlock (1837-1911)

Holled’s son Darrell was born at Box. He went into the ministry as well, graduating Wadham College, Oxford in 1854, receiving his bachelors in 1859 and Masters in 1866, was the curate of Hambleton, Buckinghamshire, 1880-82, and then moved to Yale, British Columbia, Canada in 1882.[37] He did not take up his father’s position at St Thomas à Becket. As mentioned above, he inherited a substantial amount of money from his uncle and aunt Sudell in 1858, at just twenty-one. Two years later he had married Alice Wise Saward (1838-1876), daughter of an actuary.[38] The couple moved frequently around southern England: in the 1861 census for Limpsfield, Surrey, Darrell Horlock was a shareholder while in 1871 for North Tamerton, Cornwall he was a landowner and farmer, in both instances he had four servants. We know at some point in-between he lived near Oxford as he obtained his masters degree in 1866 as well as showing up in the rolls of Masonic Lodge members.[39] All-in-all, he was living the life of an unemployed gentleman. |

Alice died in July 1876. In 1878 he married Margaret Catherine Smith of North Tamerton, 18 years his junior, daughter of Rev Richard Chamberlain Smith, [40] rector at North Tamerton and an Oxford graduate, though a generation ahead of Darrell.[41] They moved back to Wadham College, where he showed up in the 1878 Poll Books and Electoral Registers. As already noted, he became a vicar first in Buckinghamshire and within the year moved to British, Columbia, where he remained until at least 1887.

By 1891 he was again in England, appearing in the census at Milton-under-Wychwood, Oxfordshire, working as a clerk for the church. He was still able to employ two servants. By the 1901 census he had moved into the vicarage, though still acting only as the clerk, which allowed him to afford three servants. Like previous Horlocks he had lived well enough but unlike them also managed to increase his wealth. When he died in February 1911 he left his wife £10,493, worth £3.8 million today.[42]

Darrell never had children. His wife Margaret died in 1923, leaving an estate worth nearly £2 million today to two male friends rather than her nieces and nephews.[43]

Elizabeth Horlock (1834-1920)

In January 1861 she married Rev Thomas Sweetapple of Tidworth, Wiltshire.[44] Unfortunately her husband died just a few years later in 1867. Unlike so many of the reverends in this family, Thomas left less than £1,500 to his widow.[45] Fortunately for her, Elizabeth had her own money. Despite being widowed, Elizabeth too, like her brother, lived well with three or four servants per census but must have looked after her Sudell inheritance. When she passed away in December 1920 she left £11,413, equivalent today to over £1.2 million.[46] The couple only had one child, a son, who lived with his mother until his late in life marriage.

Rev Henry Darrell Suddell Sweetapple (1862-1953)

Henry Darrell Suddell Sweetapple was the grandson of Holled Darrell Cave Smith Webb Horlock via the latter’s daughter Elizabeth. He was another Oxford graduate, this time from Queen’s College. He received his master’s degree in 1886 and had church postings in Gloucestershire, Hampshire, and finally Babcary, Somerset (his father’s last posting too). Henry was vicar of Box for a very short time. He was ordained into Box in 1920 but by 1923 he was living at the rectory, Hawkridge, Dulverton, Somerset.[47]

By 1891 he was again in England, appearing in the census at Milton-under-Wychwood, Oxfordshire, working as a clerk for the church. He was still able to employ two servants. By the 1901 census he had moved into the vicarage, though still acting only as the clerk, which allowed him to afford three servants. Like previous Horlocks he had lived well enough but unlike them also managed to increase his wealth. When he died in February 1911 he left his wife £10,493, worth £3.8 million today.[42]

Darrell never had children. His wife Margaret died in 1923, leaving an estate worth nearly £2 million today to two male friends rather than her nieces and nephews.[43]

Elizabeth Horlock (1834-1920)

In January 1861 she married Rev Thomas Sweetapple of Tidworth, Wiltshire.[44] Unfortunately her husband died just a few years later in 1867. Unlike so many of the reverends in this family, Thomas left less than £1,500 to his widow.[45] Fortunately for her, Elizabeth had her own money. Despite being widowed, Elizabeth too, like her brother, lived well with three or four servants per census but must have looked after her Sudell inheritance. When she passed away in December 1920 she left £11,413, equivalent today to over £1.2 million.[46] The couple only had one child, a son, who lived with his mother until his late in life marriage.

Rev Henry Darrell Suddell Sweetapple (1862-1953)

Henry Darrell Suddell Sweetapple was the grandson of Holled Darrell Cave Smith Webb Horlock via the latter’s daughter Elizabeth. He was another Oxford graduate, this time from Queen’s College. He received his master’s degree in 1886 and had church postings in Gloucestershire, Hampshire, and finally Babcary, Somerset (his father’s last posting too). Henry was vicar of Box for a very short time. He was ordained into Box in 1920 but by 1923 he was living at the rectory, Hawkridge, Dulverton, Somerset.[47]

|

In 1909 Henry married Mary Beatruce Laurie (1972-1953) [48], daughter of Lieutenant General John Wimburn Laurie, one-time Member of Parliament for Pembrokeshire and in 1906 Mayor of Paddington. He was a fairly wealthy man with properties in both London and Nova Scotia, Canada. Somewhere between the 1911 census and 1923 when the family was travelling between England and Canada, the family had added Henry’s mother’s maiden name of Horlock to their surname. Canadian passenger lists show numerous voyages of family members between England and Nova Scotia under Sweetapple-Horlock.

Henry and Elizabeth Sweetapple both died in 1953, leaving two children: Elizabeth Darrell Halliburton Sweetapple-Horlock (1914-2015), and Henry Wimburn Sudell Sweetapple-Horlock (1915-2009). Both preferred to drop the Sweetapple. Neither had children. Left: Henry Wimburn Sudell Horlock |

Horlock family of Trowbridge

While I have not undertaken an exhaustive examination of the Horlock line beyond 1700, a cursory investigation takes the family back to Thomas Horlock, born in 1604 to Thomas and Edeth Horlocke.[49] A Thomas Horlock married Jane Bastard at Trowbridge 15 November 1541. It is uncertain if it was Thomas of Trowbridge or, as some suggest, another Thomas Horlock who came from Devon. The latter Thomas’ apparent parentage takes the family back to Barnstable, Devon in the 15th century, but documentation is lacking. There certainly were Horlocks in Barnstable in the 16th century, and even a Rayliegh William Webb Horlock died there in 1853.[50] This person is of some interest. He was baptised at Marshfield on the fourth September 1828, son of William Horlock, gentleman, and his wife Mary Ann.[51] A person of that name was in an insane asylum at Kingsdown House, Box, in 1850.[52] It is likely he was a relative of the Horlocks at Ashwick Hall but the precise connection has not yet been made. Is his dying at Barnstable a clue of a family connection to the county? The earliest Devon Horlocks I have found a document for is Sir Thomas Horlock, rector of Charles, 9 May 1424, in the register of Edmund Lacy, Bishop of Exeter, 1420-1455. Perhaps he is behind the line of Thomas Horlocks in Wiltshire, perhaps not.

Horlock family of Dorset

When researching the Ashwicke and Box Horlock family a person must be careful not to mistakenly assign records that pertain to the Dorset Horlocks, as the same first names frequently arise. The two families were indeed connected but by the 19th century they were distinct branches. Isaac Webb Horlock’s grandfather was also named Isaac Horlock.[53] He was an apothecary from Blandford Forum, Dorset. The latter’s parentage has not been proven yet. The problem seems to be a dearth of documentation, as Blandford Forum was almost leveled in a disastrous fire in 1731, which destroyed so many records. However, he left behind a will and was mentioned as a friend, not therefore a brother or son, in the will of William Horlock of Blandon Forum who died in 1695.[54] It is probable Isaac was a relative of that William Horlock. Isaac Horlock the apothecary died in 1735 and was buried in the same graveyard of St Peter, Blandford Forum, as the aforesaid William. That same year a Thomas Horlock was also buried there, as well as a Henry Horlock in 1737. There is a long history of Horlocks in the area. Two Williams and a Thomas Horlocke are recorded on the Protestation Returns of 1641 for Blandford Forum.[55] Discerning how they all actually relate though is a challenge.

Horlick surname

Likewise the name Horlick arises. In a few records the Box family is given the name Horlick, but these are clerical errors.

The Horlock family that is the subject of this review did not use Horlick as an option. The Horlick family found in the United States is thought to be related. The documentation I have perused thus far suggests their connection to the Horlock family of Blanford Forum, Dorset. But that was prior to the middle of the 18th century. Since then the Horlicks of the malt beverage fame are found in Gloucestershire, 40 miles north of Bristol around Cranham and Ruardean. So the relationship with the Box Horlock family is very distant.

While I have not undertaken an exhaustive examination of the Horlock line beyond 1700, a cursory investigation takes the family back to Thomas Horlock, born in 1604 to Thomas and Edeth Horlocke.[49] A Thomas Horlock married Jane Bastard at Trowbridge 15 November 1541. It is uncertain if it was Thomas of Trowbridge or, as some suggest, another Thomas Horlock who came from Devon. The latter Thomas’ apparent parentage takes the family back to Barnstable, Devon in the 15th century, but documentation is lacking. There certainly were Horlocks in Barnstable in the 16th century, and even a Rayliegh William Webb Horlock died there in 1853.[50] This person is of some interest. He was baptised at Marshfield on the fourth September 1828, son of William Horlock, gentleman, and his wife Mary Ann.[51] A person of that name was in an insane asylum at Kingsdown House, Box, in 1850.[52] It is likely he was a relative of the Horlocks at Ashwick Hall but the precise connection has not yet been made. Is his dying at Barnstable a clue of a family connection to the county? The earliest Devon Horlocks I have found a document for is Sir Thomas Horlock, rector of Charles, 9 May 1424, in the register of Edmund Lacy, Bishop of Exeter, 1420-1455. Perhaps he is behind the line of Thomas Horlocks in Wiltshire, perhaps not.

Horlock family of Dorset

When researching the Ashwicke and Box Horlock family a person must be careful not to mistakenly assign records that pertain to the Dorset Horlocks, as the same first names frequently arise. The two families were indeed connected but by the 19th century they were distinct branches. Isaac Webb Horlock’s grandfather was also named Isaac Horlock.[53] He was an apothecary from Blandford Forum, Dorset. The latter’s parentage has not been proven yet. The problem seems to be a dearth of documentation, as Blandford Forum was almost leveled in a disastrous fire in 1731, which destroyed so many records. However, he left behind a will and was mentioned as a friend, not therefore a brother or son, in the will of William Horlock of Blandon Forum who died in 1695.[54] It is probable Isaac was a relative of that William Horlock. Isaac Horlock the apothecary died in 1735 and was buried in the same graveyard of St Peter, Blandford Forum, as the aforesaid William. That same year a Thomas Horlock was also buried there, as well as a Henry Horlock in 1737. There is a long history of Horlocks in the area. Two Williams and a Thomas Horlocke are recorded on the Protestation Returns of 1641 for Blandford Forum.[55] Discerning how they all actually relate though is a challenge.

Horlick surname

Likewise the name Horlick arises. In a few records the Box family is given the name Horlick, but these are clerical errors.

The Horlock family that is the subject of this review did not use Horlick as an option. The Horlick family found in the United States is thought to be related. The documentation I have perused thus far suggests their connection to the Horlock family of Blanford Forum, Dorset. But that was prior to the middle of the 18th century. Since then the Horlicks of the malt beverage fame are found in Gloucestershire, 40 miles north of Bristol around Cranham and Ruardean. So the relationship with the Box Horlock family is very distant.

Wimburn Sweetapple-Horlock Family Tree

Isaac Horlock of Blandon Forum married Mary Hussey

Children: Mary, Susanna, Thomas, and Benjamin

Benjamin Horlock married Sarah Mortimer

Children: Isaac Horlock (after marriage added Webb)

Isaac Webb Horlock married Lucy Miller

Children: Maria Charlotte, Lucy, Isaac William Webb Horlock, George, George, Susanna Jemima and Sarah

Isaac William Webb Holock married Ann Smith

Children: Isaac John Webb, Knightly William Webb, and Holled Darrell Cave Smith

Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock married Elizabeth Sudell

Children: Elizabeth, and Darrell Holled Webb

Elizabeth Horlock married Thomas Sweetapple

Children: Henry Darrell Sudell married Mary Laurie

Henry Darrell Sudell Sweetapple (later hyphenated Horlock) married Mary Beatrice Halliburton Laurie

Children: Elizabeth Darrell Halliburton, and Henry Wimburn Sudell

Isaac Horlock of Blandon Forum married Mary Hussey

Children: Mary, Susanna, Thomas, and Benjamin

Benjamin Horlock married Sarah Mortimer

Children: Isaac Horlock (after marriage added Webb)

Isaac Webb Horlock married Lucy Miller

Children: Maria Charlotte, Lucy, Isaac William Webb Horlock, George, George, Susanna Jemima and Sarah

Isaac William Webb Holock married Ann Smith

Children: Isaac John Webb, Knightly William Webb, and Holled Darrell Cave Smith

Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock married Elizabeth Sudell

Children: Elizabeth, and Darrell Holled Webb

Elizabeth Horlock married Thomas Sweetapple

Children: Henry Darrell Sudell married Mary Laurie

Henry Darrell Sudell Sweetapple (later hyphenated Horlock) married Mary Beatrice Halliburton Laurie

Children: Elizabeth Darrell Halliburton, and Henry Wimburn Sudell

|

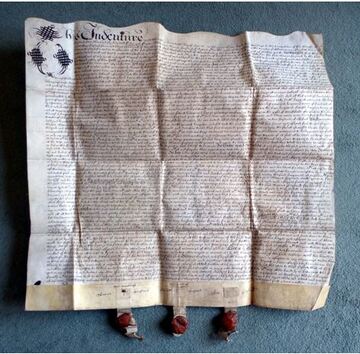

Land deeds in possession of

Henry Wimburn Sudell Sweetapple-Horlock 1654 Nicholas Webb of Marshfield, Gloucestershire. William Webb (deceased) and Christopher Webb, his son and heir apparent. 1662 William Webb of Marshfield 1679 William Webb of Marshfield and Robert Webb of Middle Temple, London (brother of William and apparently a lawyer) 1713 William Webb of Ashwick, Marshfield 1729 Lucy Webb of Marshfield (spinster) 1735 Lucy Webb of Ashwicke Marshfield (spinster) 1785 William Webb the younger 1858 Darrell Holled Webb Horlock of Box, Wiltshire |

References

[1] Clergy of the Church of England Record ID 14545

[2] Will of Pancefort Miller, 21 Dec 1726, PROB 11/628, 14 Feb 1729, Perogative Court of Canterbury, UK National Archives

[3] Details of the painting confirmed through the assistance of David Taylor

[4] Will of George Miller, 6 Nov 1732, proved 10 May 1740, England & Wales, Perogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1538, UK National Archives

[5] Will of William Webb, dated 1716, probated 1725, UK National Archives PROB 11/604/204

[6] London Magazine, or Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer, June 1754, p.284, Marriages and Births

[7] UK Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893

[8] Banking in the Reign of George III, 109, Stephen Clews, Bath Spa University

[9] Bath in Time

[10] UK City and County Directories, 1766-1946

[11] Gloucestershire, England, Land Tax Records, 1713-1833

[12] UK City and County Directories, 1766-1946

[13] Arthur Schomberg, The Monumental Inscriptions of the Box Church, County Wilts, The Genealogist (New Series), page 181, and Keith W Murray (ed.), Vol. X, George Bell & Sons, London, 1894.

[14] England and Wales, Christening Index, 1530-1980

[15] ibid

[16] Will of Susanna Jemima (Horlock) Hicks, 28 Jan 1741, PROB 11/2054, 26 Apr 1747, Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers, UK National Archives

[17] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[18] Clergy of the Church of England Database, 1540-1835, ID: 336904

[19] England and Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1348-1858

[20] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[21] Cases in the English Courts of Common Law and Equity, 1852-1854, Horlock vs. Horlock 1852

[22] 1871 England census

[23] The Internet Archive, under Knightley William Horlock

[24] Gloucestershire, England, Prison Records 1728-1914

[25] History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Hampshire and the Isle of Wright, 1878, p.675

[26] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[27] Ibid

[28] England and Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892

[29] England & Wales Select Marriages, 1538-1973

[30] Clergy of the Church of England Record ID 94932

[31] British History Online

[32] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[33] Ibid

[34] Great Western Railway shareholders 1857 and 1858

[35] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[36] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[37] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[38] London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1928

[39] England, United Grand Lodge of England Freemason Membership Registers, 1751-1921

[40] England & Wales Select Marriages, 1538-1973

[41] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[42] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[43] Ibid

[44] England & Wales Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1837-1915

[45] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[46] Ibid

[47] Clergy of the Church of England Record ID

[48] London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921

[49] England Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975

[50] England and Wales deaths, 1837-2007

[51] Gloucester, England, Church of England Baptisms 1813-1913

[52] UK, Lunacy Patients Admission Records, 1846-1912

[53] Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions, UK National Archives, PROB 11.636/330, Horlock, Isaac, Apothecary of Blanford Forum, will, 1730; Dorset, England, Wills and Probates, 1565-1858

[54] England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858

[55] Dorset Online Parish Clerks web site, Blandford Forum

[1] Clergy of the Church of England Record ID 14545

[2] Will of Pancefort Miller, 21 Dec 1726, PROB 11/628, 14 Feb 1729, Perogative Court of Canterbury, UK National Archives

[3] Details of the painting confirmed through the assistance of David Taylor

[4] Will of George Miller, 6 Nov 1732, proved 10 May 1740, England & Wales, Perogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1538, UK National Archives

[5] Will of William Webb, dated 1716, probated 1725, UK National Archives PROB 11/604/204

[6] London Magazine, or Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer, June 1754, p.284, Marriages and Births

[7] UK Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893

[8] Banking in the Reign of George III, 109, Stephen Clews, Bath Spa University

[9] Bath in Time

[10] UK City and County Directories, 1766-1946

[11] Gloucestershire, England, Land Tax Records, 1713-1833

[12] UK City and County Directories, 1766-1946

[13] Arthur Schomberg, The Monumental Inscriptions of the Box Church, County Wilts, The Genealogist (New Series), page 181, and Keith W Murray (ed.), Vol. X, George Bell & Sons, London, 1894.

[14] England and Wales, Christening Index, 1530-1980

[15] ibid

[16] Will of Susanna Jemima (Horlock) Hicks, 28 Jan 1741, PROB 11/2054, 26 Apr 1747, Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers, UK National Archives

[17] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[18] Clergy of the Church of England Database, 1540-1835, ID: 336904

[19] England and Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1348-1858

[20] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[21] Cases in the English Courts of Common Law and Equity, 1852-1854, Horlock vs. Horlock 1852

[22] 1871 England census

[23] The Internet Archive, under Knightley William Horlock

[24] Gloucestershire, England, Prison Records 1728-1914

[25] History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Hampshire and the Isle of Wright, 1878, p.675

[26] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[27] Ibid

[28] England and Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892

[29] England & Wales Select Marriages, 1538-1973

[30] Clergy of the Church of England Record ID 94932

[31] British History Online

[32] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[33] Ibid

[34] Great Western Railway shareholders 1857 and 1858

[35] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[36] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[37] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[38] London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1928

[39] England, United Grand Lodge of England Freemason Membership Registers, 1751-1921

[40] England & Wales Select Marriages, 1538-1973

[41] Oxford University Alumni 1500-1886

[42] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[43] Ibid

[44] England & Wales Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1837-1915

[45] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966, 1973-1995

[46] Ibid

[47] Clergy of the Church of England Record ID

[48] London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921

[49] England Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975

[50] England and Wales deaths, 1837-2007

[51] Gloucester, England, Church of England Baptisms 1813-1913

[52] UK, Lunacy Patients Admission Records, 1846-1912

[53] Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions, UK National Archives, PROB 11.636/330, Horlock, Isaac, Apothecary of Blanford Forum, will, 1730; Dorset, England, Wills and Probates, 1565-1858

[54] England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858

[55] Dorset Online Parish Clerks web site, Blandford Forum