|

Understanding Rev HDCS Horlock Alan Payne

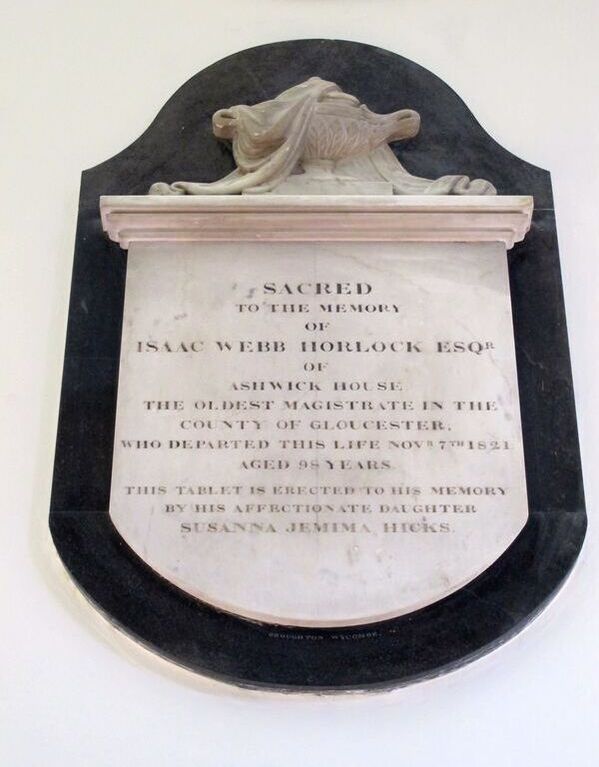

April 2023 It is difficult to make objective judgements about people, even contemporaries, because very few individuals are wholly good or bad, or consistent in their attitudes. The best you can say about Rev Holled DCS Horlock is that he was an unusual man. At the end of his time in Box his behaviour was weird, perhaps unhinged. He was a strange man. There are no contemporary photographs of Rev Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock (1808-1901), no record of his sermons or religious inclinations, no epitaph in Box Church (although there was one to his father). When he left Box in 1874, he was aged 66 and had been vicar in Box for 43 years. His father Isaac William Webb Horlock had been vicar for 30 years previously and the family owned the advowsen (right to appoint the vicar) for 77 years. In that time, they had become extremely wealthy. They lived in a property called The Old Parsonage, next door to the church in the area now occupied by Box House. When the Old Parsonage burnt down in 1805, William Horlock built the current Box House and the family lived in greater comfort in a more modern property. |

The State of Church of England

In the 1840s, the Anglican Church was undergoing a period of spiritual review. The so-called Oxford Movement had issued a number of Tracts for the Times advocating more Roman Catholic practices into the Church of England, including the form of service and ceremony, the creation of Anglican monastic orders, and the importance of the Holy Communion ritual in the conversion of the body and blood of Christ. The leaders of the movement also advocated a broader social political policy of fair wages and improved industrial conditions. The movement’s main success was the creation of Hymns Ancient and Modern but was faltering by the 1870s. One of the leading Tractarians was Liberal Party leader William Gladstone who was defeated as prime minister in the 1874 General Election. None of the Tractarian aspirations seems to have been adopted by Rev Horlock. Indeed, one of the few comments made about his religious inclination says he was a typical Low Churchman (giving little attention to ritual).[1]

In September 1843 Rev Horlock applied to the bishop of Gloucester that Church of England services only should be held at Kingsdown Chapel rather than Dissenting services and refuting that the area was a stronghold of dissent.[2] It is unclear why the application was made or where the chapel was located as the first Kingsdown Methodist Chapel was built in 1869. The friction with Methodist adherents wasn’t a personal grudge by Rev Horlock because his successor, Rev George Gardiner, forbad Methodist burials in the Cemetery and refused admission to the chapel there.[3]

Rev Horlock was an evangelist (zealous preaching often by personal statements) at a time when Box had already moved to fuller Dissenting preaching with the growth of the Methodist movement.[4] Example of his low church Anglican beliefs included supporting the missionary movement.[5] This appears to be confirmed in 1898 when he preached two eloquent services at Christmas at Newton Poppleford.[6] This was amplified later at the harvest supper in the same year when he preached about the Parable of the Sower of seed on rocky ground and Psalm 65:9 Thou visiteth the earth and waterest it (God directing his blessing to those who merited).[7] Perhaps, Rev Horlock was thinking of himself in these sermons.

Local Hostility

There is evidence of Rev Horlock seeking to claim land and buildings as personal possessions from as early as 1834 when he contests that Springfield Cottages (then referred to as the Schoolhouse) were personal property of the family rather than belonging to the school charitable trust.[8] This was refuted by solicitors Mant & Bruce, probably acting on behalf of the Northey family.

The closest we get to personal comments about Rev Holled Horlock are newspaper reports in the 1850s, when strange reports were made about him. In 1853 Henry Sprague, a medical man living in Box, was charged along with Benjamin Bullock, sexton, with writing to the vicar and to Miss Horlock threatening to kill them and encouraging their servants to poison their food.[9] In a diatribe of invectiveness, the letter spoke of the old, damnable doctor (Rev Horlock) oppressing the righteous … You could not spare anything for a famishing old man and his family… never was there such a surly, parsimonious, ugly, filthy, covetous, hypocritical feller. Henry’s father Dr John H Sprague (1784-1865) had been appointed as surgeon in the village on the nomination of Rev Horlock in 1851. But then the vicar changed his mind and started to advocate treatment by Dr Nash. Henry claimed that to my father you have proved a villain and deceiver and accused him of fermenting agitation against his father by young boys in the village.[10]

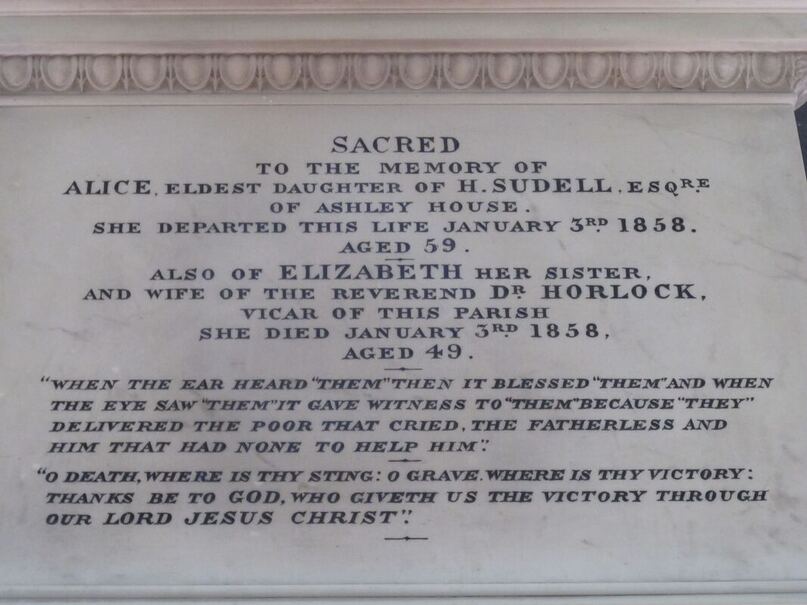

The story of the deaths of Rev Horlock’s wife Elizabeth and sister-in-law Alice Sudell in January 1858 were the talk of the village. The whole family had a Christmas celebratory meal at Box House next to Box Church, the two women fell ill and died early January. Villagers suggested they were poisoned, the Church Commissioners claimed it was due to fumes emanating from the churchyard and stopped future burials there. A letter (in a similar tone to the 1853 letters) was produced to the coroner purporting to be from H Barrington to George Aust, a Box carpenter, urging him to blow up the family with gunpowder.[11] There is an epitaph to the Suddell sisters in the South Aisle of Box Church with the inscription: When the ear heard them, then it blessed them and, when the eye saw them, it gave witness to them because they delivered the poor that cried, the fatherless and him that none to help him. O Death where is thy sting: Oh grave where is thy victory. Thanks be to God who givest us victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. It doesn’t sound like a tribute from a grieving husband and brother-in-law.

In the 1840s, the Anglican Church was undergoing a period of spiritual review. The so-called Oxford Movement had issued a number of Tracts for the Times advocating more Roman Catholic practices into the Church of England, including the form of service and ceremony, the creation of Anglican monastic orders, and the importance of the Holy Communion ritual in the conversion of the body and blood of Christ. The leaders of the movement also advocated a broader social political policy of fair wages and improved industrial conditions. The movement’s main success was the creation of Hymns Ancient and Modern but was faltering by the 1870s. One of the leading Tractarians was Liberal Party leader William Gladstone who was defeated as prime minister in the 1874 General Election. None of the Tractarian aspirations seems to have been adopted by Rev Horlock. Indeed, one of the few comments made about his religious inclination says he was a typical Low Churchman (giving little attention to ritual).[1]

In September 1843 Rev Horlock applied to the bishop of Gloucester that Church of England services only should be held at Kingsdown Chapel rather than Dissenting services and refuting that the area was a stronghold of dissent.[2] It is unclear why the application was made or where the chapel was located as the first Kingsdown Methodist Chapel was built in 1869. The friction with Methodist adherents wasn’t a personal grudge by Rev Horlock because his successor, Rev George Gardiner, forbad Methodist burials in the Cemetery and refused admission to the chapel there.[3]

Rev Horlock was an evangelist (zealous preaching often by personal statements) at a time when Box had already moved to fuller Dissenting preaching with the growth of the Methodist movement.[4] Example of his low church Anglican beliefs included supporting the missionary movement.[5] This appears to be confirmed in 1898 when he preached two eloquent services at Christmas at Newton Poppleford.[6] This was amplified later at the harvest supper in the same year when he preached about the Parable of the Sower of seed on rocky ground and Psalm 65:9 Thou visiteth the earth and waterest it (God directing his blessing to those who merited).[7] Perhaps, Rev Horlock was thinking of himself in these sermons.

Local Hostility

There is evidence of Rev Horlock seeking to claim land and buildings as personal possessions from as early as 1834 when he contests that Springfield Cottages (then referred to as the Schoolhouse) were personal property of the family rather than belonging to the school charitable trust.[8] This was refuted by solicitors Mant & Bruce, probably acting on behalf of the Northey family.

The closest we get to personal comments about Rev Holled Horlock are newspaper reports in the 1850s, when strange reports were made about him. In 1853 Henry Sprague, a medical man living in Box, was charged along with Benjamin Bullock, sexton, with writing to the vicar and to Miss Horlock threatening to kill them and encouraging their servants to poison their food.[9] In a diatribe of invectiveness, the letter spoke of the old, damnable doctor (Rev Horlock) oppressing the righteous … You could not spare anything for a famishing old man and his family… never was there such a surly, parsimonious, ugly, filthy, covetous, hypocritical feller. Henry’s father Dr John H Sprague (1784-1865) had been appointed as surgeon in the village on the nomination of Rev Horlock in 1851. But then the vicar changed his mind and started to advocate treatment by Dr Nash. Henry claimed that to my father you have proved a villain and deceiver and accused him of fermenting agitation against his father by young boys in the village.[10]

The story of the deaths of Rev Horlock’s wife Elizabeth and sister-in-law Alice Sudell in January 1858 were the talk of the village. The whole family had a Christmas celebratory meal at Box House next to Box Church, the two women fell ill and died early January. Villagers suggested they were poisoned, the Church Commissioners claimed it was due to fumes emanating from the churchyard and stopped future burials there. A letter (in a similar tone to the 1853 letters) was produced to the coroner purporting to be from H Barrington to George Aust, a Box carpenter, urging him to blow up the family with gunpowder.[11] There is an epitaph to the Suddell sisters in the South Aisle of Box Church with the inscription: When the ear heard them, then it blessed them and, when the eye saw them, it gave witness to them because they delivered the poor that cried, the fatherless and him that none to help him. O Death where is thy sting: Oh grave where is thy victory. Thanks be to God who givest us victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. It doesn’t sound like a tribute from a grieving husband and brother-in-law.

In 1865 a widow named Mrs Tayler was reported as an imposter using Rev Horlock’s name to obtain money under false pretences but I have found no other detail, although this period in the vicar's life is full of strange details about him.[12] We know that he was interested in animals and won prizes for Cross-Bred Chickens in the Chippenham Agricultural Show of 1860.[13] In 1862 he held his first court leet (half-yearly meeting) as lord of the manor house in Marshfield.[14] This seems a curiously outdated event, appointing a bailiff on behalf of the lord and asserting authority over tenants but the vicar appears to have wanted to be personally involved.

It was Rev Horlock’s opposition to the establishment of a Schools Board in 1871 which caused most local opprobrium. The provision of schooling for Church of England village children was severely restricted to the old charity schools in the top floor of the workhouse and a girl’s school at Henley. No provision had been made for Dissenting children and Methodists had built their own schoolrooms where they could receive their own brand of education. Meanwhile provision in the Church of England areas had declined and the vicar, as the sole trustee of the charity school trust, refused to use trust funds of £80 a year to improve the situation or to appoint additional trustees. In this, he was opposed by local landowners Col George Wilbraham Northey, Thomas Poynder and vociferously by the lawyer William Adair Bruce.[15] Locals organized a parish meeting at the new church vestry room at which 57 leading ratepayers petitioned for an application to form a Schools Board for Box (prior to the creation of a new school).[16]

It was Rev Horlock’s opposition to the establishment of a Schools Board in 1871 which caused most local opprobrium. The provision of schooling for Church of England village children was severely restricted to the old charity schools in the top floor of the workhouse and a girl’s school at Henley. No provision had been made for Dissenting children and Methodists had built their own schoolrooms where they could receive their own brand of education. Meanwhile provision in the Church of England areas had declined and the vicar, as the sole trustee of the charity school trust, refused to use trust funds of £80 a year to improve the situation or to appoint additional trustees. In this, he was opposed by local landowners Col George Wilbraham Northey, Thomas Poynder and vociferously by the lawyer William Adair Bruce.[15] Locals organized a parish meeting at the new church vestry room at which 57 leading ratepayers petitioned for an application to form a Schools Board for Box (prior to the creation of a new school).[16]

Forming a New Vicarage

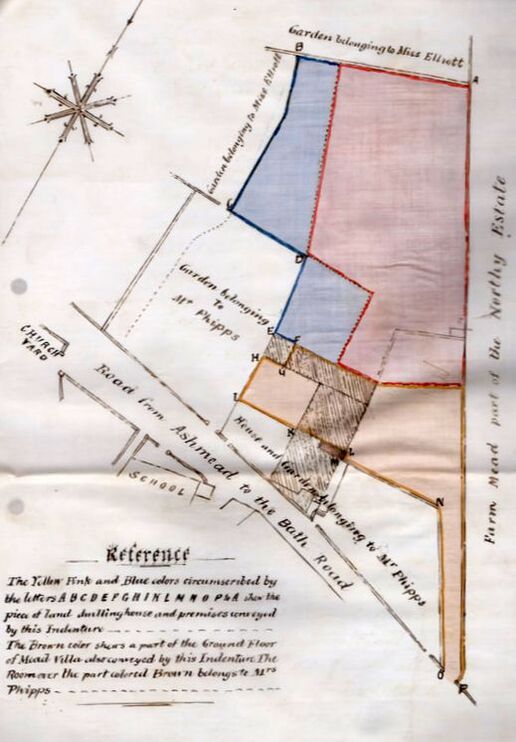

The formation of the Vicarage property was complex. The conveyance is a huge document crowded with repetitions (worse than the usual legal circumlocutions) as if the circumstances were uncertain: And whereas the said Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock some time since undertook that the said hereditament hereinafter expressed to be hereby assured should be appropriated as and for a residence for the vicar of the said parish of Box…. The land selected was adjacent to the Church at the south east corner.

The formation of the Vicarage property was complex. The conveyance is a huge document crowded with repetitions (worse than the usual legal circumlocutions) as if the circumstances were uncertain: And whereas the said Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock some time since undertook that the said hereditament hereinafter expressed to be hereby assured should be appropriated as and for a residence for the vicar of the said parish of Box…. The land selected was adjacent to the Church at the south east corner.

|

First, an entrance had to be made from the A4 road by acquiring a strip of land from Harriet Barlow Phipps at Springfield Villa, widow of John Phipps. During this period (possibly in 1867) the vicar acquired both Springfield Villa and Mead Villa and the conveyance sought to separate the land areas into individual properties. Rev Horlock attributed credibility to his chosen site by referring to the messuage of Parsonage House shown on the Allen 1626 map at one time occupied by George Lee and afterwards by George Phillips.

On 3 August 1874 the vicar sold Mead Villa to William Stancombe of Blounts Court, Devizes. Rev Horlock had already sold the advowsen of Box Church to the same man for £600. Stancombe bought the advowsen to appoint his son-in-law George Gardiner, who moved into Mead Villa on the vicar’s departure. The conveyance seems to exaggerate the grandeur of the building calling it Mead Villa Estate .. a proper residence for the Vicar of Box. Rev Horlock appears to have organized the transfer over a number of years. He bought Mead Villa on 28 November 1867 from the previous owners listed as Rev William Hazeldine of Temple Church, Bristol and Elizabeth Sweetapple (Rev Horlock’s daughter). He also bought land for a garden from Dr Joseph Nash of The Wilderness. It was all a closed arrangement as Rev William Hazeldine was a family friend of the Stancombes and the vicar was the patron of Joseph Nash.[17] To soften the purchase price, the vicar threw the pew number 5 in Box Church as part of the price. |

In this way Rev Horlock avoided any mention of the previous vicarage, Box House, where he was living in 1874. Mead Villa was then advertised for rent, described as Villa, near Church .. with coach-house, stable, flower and kitchen gardens .. very good dining room, and drawing room, seven good bedrooms and hot and cold water.[18]

Leaving Box in Amazing Circumstances

Rev Holled Horlock appears a very different person when he left Wiltshire and moved to South Devon in 1874-75. In Box he guarded his wealth carefully and incurred great local opposition but, when he moved to Newton Poppleford, he appeared to be humble and more dedicated to his religious duties. Surprisingly after such a long tenure, his departure from Box was largely ignored by parishioners and few words of thanks were offered.

Leaving Box in Amazing Circumstances

Rev Holled Horlock appears a very different person when he left Wiltshire and moved to South Devon in 1874-75. In Box he guarded his wealth carefully and incurred great local opposition but, when he moved to Newton Poppleford, he appeared to be humble and more dedicated to his religious duties. Surprisingly after such a long tenure, his departure from Box was largely ignored by parishioners and few words of thanks were offered.

|

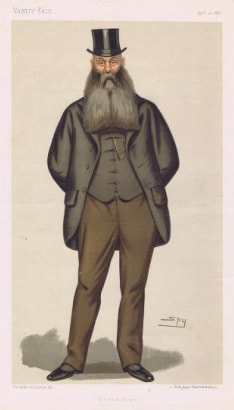

The reason for this change appears in a single sentence in the North Wilts Herald of 14 May 1877: The Rev Dr Horlock, late vicar of Box, has been adjudged a bankrupt. The details of the bankruptcy are simply astounding, sued by another clergyman for property damage. Rev Horlock was lord of the manor of Tormarton and used that right to take the curacy at Tormarton, Gloucestershire after leaving Box. He took up residence in the rectory in October 1875, at that time in the ownership of Rev EJ Everard.[19] Rev Horlock brought a menagerie of animals with him including twenty-seven white mice, three loose pigeons, a hawk (allowed to roam about the place), a dove which went in and out of the rooms, nine small birds, five large dogs, three pugs, a Skye terrier, a squirrel, three cats, five horses and a monkey. By the time he vacated the property in April 1876, the animals had occupied every room converting them from bedrooms to stabling and caused substantial damage to decorations, carpets and curtains.

There have been numerous loal anecdotes that Rev Horlock kept monkeys in Box House but it seemed so ludicrous that David Ibberson speculated that they might really have been non-white servants (see Horlock Dynasty). This photo was found in an album kept by the Lambert family and may have been obtained by Emma Amelia Hobbs (1855-1952) who worked as a domestic servant at Box House in 1871 and later married into a branch of the family. If this speculation is correct, then Rev Horlock kept monkeys in the house and also had coloured servants working for him. Left: Unknown sitters in the Lambert archive (courtesy Margaret Wakefield) |

Rev Horlock was reported as having considerable property but his habits were very curious. Damages to the Tormarton property were assessed as between £60 and £70 (today £7,300 to £8,500).[20] The newspapers savagedthe vicar with descriptions such as this eccentric doctor of divinity and The revelation throws a curious light on the manners and customs of some country parsons in the nineteenth century.[21] The dispute became personal and Holland offered to pay £10 only (£1,200 today) but the bishop ordered him to make good the deficit.[22] Rev Horlock continued to refuse and was summoned to surrender to the district bankruptcy court at Bath at 11am on 19 May.[23]

|

Life at Newton Poppleford

When Rev Horlock moved to Newton Poppleford on the south coast of Devon, he seems to have found a more relevant parish for his beliefs. The church of St Luke was described as a small, plain building formerly a chantry then a chapel-of-ease. The vicar was allowed to preach in an entrance lodge of the Squire of Harefield in what may have resembled a house-church.[24] He took an active role as chairman of the local Conservative Party bonding closely with Devonshire MP, Sir John Kennaway, who was president of the Church Missionary Society and a notable low church supporter.[25] When Rev Horlock died at Newton Poppleford, Devon, on 28 December 1901, he was described as the oldest beneficed clergyman in the county, if not in all England.[26] His obituaries referred to him as an eloquent preacher and the service was begun, rather appropriately, with the hymn Rock of Ages.[27] At 95 years old, Rev Horlock had remained faithful to older times. |

Conclusion

Like all of us, Holled Horlock was a complicated man. He clung on to Georgian values of patronage and possession (which existed in the Church of England as much as in private ownership), whilst society around him moved away from that position to either Methodism or the ritual of the Oxford Movement. His obstinacy did little to endear him to village residents and he was increasingly vilified as a selfish, money-grabber.

It is hard not to see him as delusional with his maintenance of a domestic menagerie and his failure to deal with the judgement of his bishop in the legal case against him by Rev Everard. To modern ears, his refusal to administer correctly the charitable educational trusts deprived Box children of a proper education. In later life, he seems to have redeemed himself in the tranquil south Devon village of Newton Poppleford, where he lived quietly for a further 25 years supported by the few hundred residents of the village.

Like all of us, Holled Horlock was a complicated man. He clung on to Georgian values of patronage and possession (which existed in the Church of England as much as in private ownership), whilst society around him moved away from that position to either Methodism or the ritual of the Oxford Movement. His obstinacy did little to endear him to village residents and he was increasingly vilified as a selfish, money-grabber.

It is hard not to see him as delusional with his maintenance of a domestic menagerie and his failure to deal with the judgement of his bishop in the legal case against him by Rev Everard. To modern ears, his refusal to administer correctly the charitable educational trusts deprived Box children of a proper education. In later life, he seems to have redeemed himself in the tranquil south Devon village of Newton Poppleford, where he lived quietly for a further 25 years supported by the few hundred residents of the village.

Family Tree

Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock (1808-1901) married twice: first to Elizabeth Sudell (1809-1858) in 1832 and secondly to Charlotte Butler Houghton Clarke (1841-1898) in 1865.

Children with Elizabeth:

Elizabeth (1833-1921) who married Thomas Sweetapple (-1867);

Rev Darrell Holled Webb Horlock (1837-1911) who married Alice Saward of Limpsfield Surrey in 1860. Darrell served in British Columbia and was later vicar of Milton-in-Wychwood, Oxfordshire.

Child with Charlotte:

Annette Darrell Emily Houghton Horlock. Known as Nellie (1866-1938), never married. She was the organist at services for her father in Poppleford and described as well-known and beloved by the parishioners at St Luke’s and was buried at Newton Poppleford.

Holled Darrell Cave Smith Horlock (1808-1901) married twice: first to Elizabeth Sudell (1809-1858) in 1832 and secondly to Charlotte Butler Houghton Clarke (1841-1898) in 1865.

Children with Elizabeth:

Elizabeth (1833-1921) who married Thomas Sweetapple (-1867);

Rev Darrell Holled Webb Horlock (1837-1911) who married Alice Saward of Limpsfield Surrey in 1860. Darrell served in British Columbia and was later vicar of Milton-in-Wychwood, Oxfordshire.

Child with Charlotte:

Annette Darrell Emily Houghton Horlock. Known as Nellie (1866-1938), never married. She was the organist at services for her father in Poppleford and described as well-known and beloved by the parishioners at St Luke’s and was buried at Newton Poppleford.

References

[1] The Western Times, 11 April 1902

[2] Licence dated 16 September 1843

[3] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 7 April 1877

[4] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 12 March 1884

[5] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 6 February 1891 and West Somerset Free Press, 19 November 1892

[6] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 30 December 1898

[7] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 23 September 1898

[8] 1845 copy of letter dated 1834

[9] The Globe, 8 August 1853,

[10] The Berkshire Chronicle, 30 July 1853 repeats verbatim much of the Sprague correspondence

[11] See Sudell Deaths

[12] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 2 February 1865

[13] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 20 December 1860

[14] The Wiltshire Independent, 13 November 1862

[15] Bristol Times and Mirror, 21 April 1871

[16] Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, 15 April 1871

[17] The Gentlewoman, 9 November 1901

[18] The Bath Chronicle, 11 February 1869

[19] Royal Cornwall Gazette, 19 August 1876

[20] Illustrated London News, 12 August 1876

[21] Brecon County Times, 12 August 1876

[22] The Worcestershire Chronicle, 12 August 1876

[23] London Evening Standard, 9 May 1877

[24] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 12 March 1884

[25] The Exeter Flying Post, 21 April 1894

[26] East & South Devon Advertiser, 4 January 1902

[27] The Western Times, 2 January 1902

[1] The Western Times, 11 April 1902

[2] Licence dated 16 September 1843

[3] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 7 April 1877

[4] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 12 March 1884

[5] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 6 February 1891 and West Somerset Free Press, 19 November 1892

[6] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 30 December 1898

[7] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 23 September 1898

[8] 1845 copy of letter dated 1834

[9] The Globe, 8 August 1853,

[10] The Berkshire Chronicle, 30 July 1853 repeats verbatim much of the Sprague correspondence

[11] See Sudell Deaths

[12] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 2 February 1865

[13] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 20 December 1860

[14] The Wiltshire Independent, 13 November 1862

[15] Bristol Times and Mirror, 21 April 1871

[16] Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, 15 April 1871

[17] The Gentlewoman, 9 November 1901

[18] The Bath Chronicle, 11 February 1869

[19] Royal Cornwall Gazette, 19 August 1876

[20] Illustrated London News, 12 August 1876

[21] Brecon County Times, 12 August 1876

[22] The Worcestershire Chronicle, 12 August 1876

[23] London Evening Standard, 9 May 1877

[24] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 12 March 1884

[25] The Exeter Flying Post, 21 April 1894

[26] East & South Devon Advertiser, 4 January 1902

[27] The Western Times, 2 January 1902