Scars of Great War Alan Payne December 2021

There is nothing inherently wrong in the idea of nationalism or localism. In recent times, we saw that in the pride of the 2012 London Olympics and the 2016 Euros when the country joined together to support those representing us all. But the national pride which began to emerge in the 1920s and 1930s was different, based on famous Great War battles, patriotic military songs and an exceptionalism that claimed Britain was the greatest nation, superior to all others. The core of this patriotism centred on the British Empire, the King and Britain’s manufacturing and trading ability in the world.

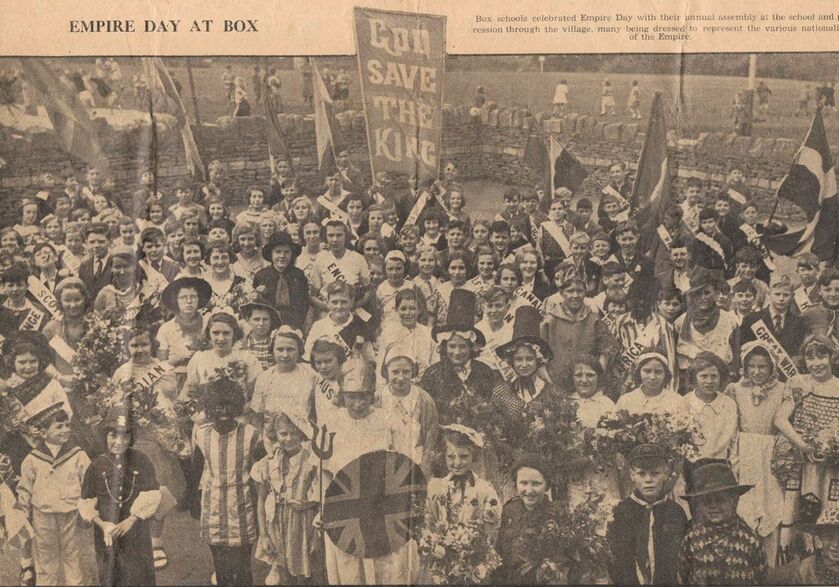

Empire Day at Box

In one respect Empire Day was great fun, when school children were given the morning off school and paraded dressed in red, white and blue on May 24, the commemoration date of Queen Victoria’s birthday. The Browning children, Jim and Anne from 5 Mead Villas, had posies of red daisies, snow on the mountain and forget-me-nots. The flowers made a colourful display and cost nothing. The children were given sashes depicting great British heroes: Queen Victoria, Nurse Cavell, Brunel, Stephenson, Longfellow, Tennyson and the countries in the Empire. Jim wore the sash of Percy Bysshe Shelley and, after the morning off, it was back to school in the afternoon.

The children were usually addressed by a local military man to remind them of great victories of the Empire: Agincourt, Trafalgar and Waterloo and that it was their duty and privilege to be part of the Empire. Proceedings culminated with a hearty rendition of God Save the King. The upper Standards then processed from the Schools to the War Memorial where there was a service and a few hymns, then back to the Schools via The Market Place for oranges and nuts given away by Alfred Shaw Mellor from Box House, as chairman of the school governors and early closing of the school.

In one respect Empire Day was great fun, when school children were given the morning off school and paraded dressed in red, white and blue on May 24, the commemoration date of Queen Victoria’s birthday. The Browning children, Jim and Anne from 5 Mead Villas, had posies of red daisies, snow on the mountain and forget-me-nots. The flowers made a colourful display and cost nothing. The children were given sashes depicting great British heroes: Queen Victoria, Nurse Cavell, Brunel, Stephenson, Longfellow, Tennyson and the countries in the Empire. Jim wore the sash of Percy Bysshe Shelley and, after the morning off, it was back to school in the afternoon.

The children were usually addressed by a local military man to remind them of great victories of the Empire: Agincourt, Trafalgar and Waterloo and that it was their duty and privilege to be part of the Empire. Proceedings culminated with a hearty rendition of God Save the King. The upper Standards then processed from the Schools to the War Memorial where there was a service and a few hymns, then back to the Schools via The Market Place for oranges and nuts given away by Alfred Shaw Mellor from Box House, as chairman of the school governors and early closing of the school.

By 1916 the day had become an institutional event throughout the British Empire to remind children that they formed part of the British Empire, and that they might think with others in lands across the sea, what it meant to be sons and daughters of such a glorious Empire.[1]

We should not ignore that this seemingly harmless level of jingoism had repercussions in the rest of Europe particularly in countries who aspired to have their own Empires. The politicisation of the event was used to reinforce the existing social hierarchy in Britain and overseas with the depiction of black faces and primitive savages for African nationalities. And the use of military songs, poems and heroes represented unbalanced role models for the minds of young children. We might contrast the military depiction of Empire Days with our modern, more uplifting multicultural Commonwealth Day and Remembrance Day.

Other similar activities were popular with adults with concerts in the Bingham Hall, often by the Scouts and Guides, culminating always with Britannia appearing in the grand finale, singing Jerusalem and the National Anthem. These traditions continued until the 1960s when cinema shows culminated with standing to respect God Save the Queen.

We should not ignore that this seemingly harmless level of jingoism had repercussions in the rest of Europe particularly in countries who aspired to have their own Empires. The politicisation of the event was used to reinforce the existing social hierarchy in Britain and overseas with the depiction of black faces and primitive savages for African nationalities. And the use of military songs, poems and heroes represented unbalanced role models for the minds of young children. We might contrast the military depiction of Empire Days with our modern, more uplifting multicultural Commonwealth Day and Remembrance Day.

Other similar activities were popular with adults with concerts in the Bingham Hall, often by the Scouts and Guides, culminating always with Britannia appearing in the grand finale, singing Jerusalem and the National Anthem. These traditions continued until the 1960s when cinema shows culminated with standing to respect God Save the Queen.

A Military Society

The inter-war years witnessed renewed respect for past military achievements. Many ex-military men continued to use their titles and honours in peacetime. It was partly to recognise their wartime contribution and in some cases this work continued after 1918. Colonel John David Beveridge Erskine DSO (3 April 1874 - 11 May 1926) and Capt Roger Alexander Legard (15 June 1891 - 29 January 1972), a bachelor from Kingsdown, used their positions to help the unemployed and invalided ex-servicemen who were otherwise uncatered for in the general recession.[2] They were instrumental with others in founding the Comrades Legion Club at Hardy House and the work of the local British Legion Relief Fund. Colonel Erskine had served before the Boer War and vowed after the First World War to do all I could to help those who came through the war.[3]

As authority and money moved away from the landed classes in Box, military men bought up properties going cheaply. Lieutenant Colonel Hugh le D Spencely acquired Ashley House in 1917 and lived there until his death in 1927. His obituary in the parish magazine recalled He was a fine man, loyal and unaffected, who served his Country and his Church with thorough devotion. His life commanded the respect of all.[4] His wife stayed in occupation of the house until 1936 and married Major Basil Owen Palmer. Captain Arthur Courtney Stewart bought Ashley Manor in 1918 and the family lived there until 1961. Ardgay House was bought by Colonel Marcus Rainsford in 1918. Sherbrooke (sometimes called Rudloe Towers) was to have been sold to Major WG Southey Harrison (late of the 3rd King’s Hussars) in 1921 but completion didn’t go through.[5] Wormcliffe House was restored by Brigadier E Felton Falkner after 1935.

The inter-war years witnessed renewed respect for past military achievements. Many ex-military men continued to use their titles and honours in peacetime. It was partly to recognise their wartime contribution and in some cases this work continued after 1918. Colonel John David Beveridge Erskine DSO (3 April 1874 - 11 May 1926) and Capt Roger Alexander Legard (15 June 1891 - 29 January 1972), a bachelor from Kingsdown, used their positions to help the unemployed and invalided ex-servicemen who were otherwise uncatered for in the general recession.[2] They were instrumental with others in founding the Comrades Legion Club at Hardy House and the work of the local British Legion Relief Fund. Colonel Erskine had served before the Boer War and vowed after the First World War to do all I could to help those who came through the war.[3]

As authority and money moved away from the landed classes in Box, military men bought up properties going cheaply. Lieutenant Colonel Hugh le D Spencely acquired Ashley House in 1917 and lived there until his death in 1927. His obituary in the parish magazine recalled He was a fine man, loyal and unaffected, who served his Country and his Church with thorough devotion. His life commanded the respect of all.[4] His wife stayed in occupation of the house until 1936 and married Major Basil Owen Palmer. Captain Arthur Courtney Stewart bought Ashley Manor in 1918 and the family lived there until 1961. Ardgay House was bought by Colonel Marcus Rainsford in 1918. Sherbrooke (sometimes called Rudloe Towers) was to have been sold to Major WG Southey Harrison (late of the 3rd King’s Hussars) in 1921 but completion didn’t go through.[5] Wormcliffe House was restored by Brigadier E Felton Falkner after 1935.

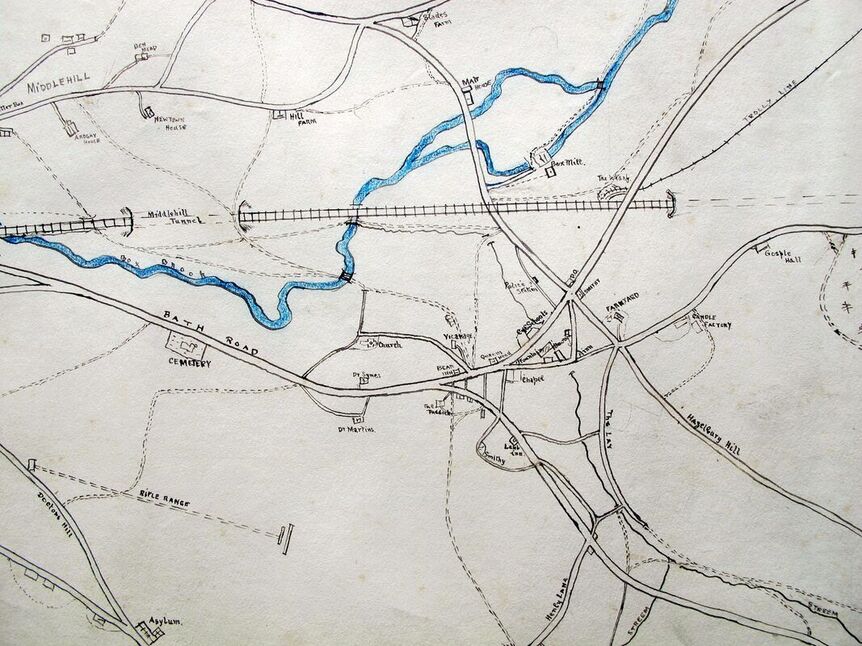

Somerset Territorials

The presence of military men at Ashley was expected annually because the Somerset Territorials used the area as a firing range. A series of butts (derived from Anglo French word bouter meaning to expel) at different distances allowed men to practice their range of shots. In 1927 the Parish Council complained about stray bullets from the exercise causing distress to the residents of Henley.[6] A petition was started in September that year by the inhabitants of Henley and Longsplatt: There is seldom an occasion when firing is in progress that the people of this place are not terrified by stray bullets but the climax was reached last Saturday week when a succession of explosive bullets dropped, some of them within a few yards of men working in the harvest field at Henley.[7]

The presence of military men at Ashley was expected annually because the Somerset Territorials used the area as a firing range. A series of butts (derived from Anglo French word bouter meaning to expel) at different distances allowed men to practice their range of shots. In 1927 the Parish Council complained about stray bullets from the exercise causing distress to the residents of Henley.[6] A petition was started in September that year by the inhabitants of Henley and Longsplatt: There is seldom an occasion when firing is in progress that the people of this place are not terrified by stray bullets but the climax was reached last Saturday week when a succession of explosive bullets dropped, some of them within a few yards of men working in the harvest field at Henley.[7]

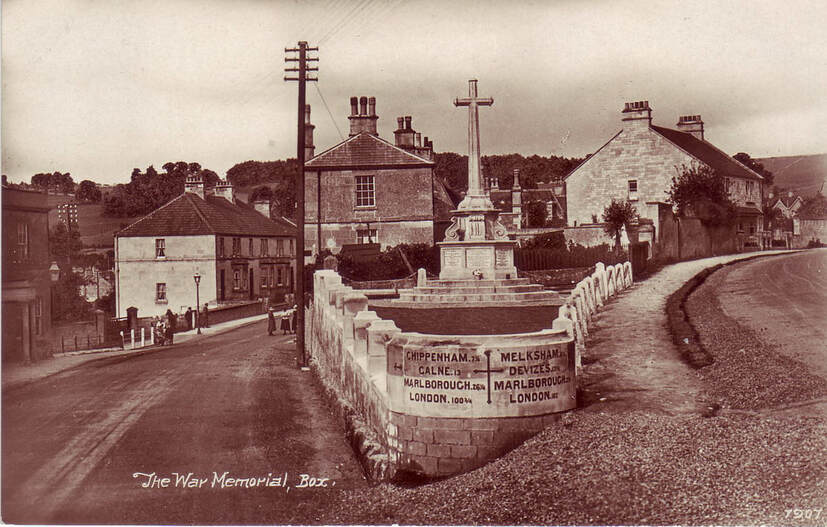

Box War Memorial

If there is one image to define village life in the inter-war years, it is probably the War Memorial on the west of the central residential area. The epitaph united all religions and none, family remembrances of tragedy and loss over the last century and, unique of all Box's unlisted buildings, it is probably the only structure which could never be redeveloped or improved.

If there is one image to define village life in the inter-war years, it is probably the War Memorial on the west of the central residential area. The epitaph united all religions and none, family remembrances of tragedy and loss over the last century and, unique of all Box's unlisted buildings, it is probably the only structure which could never be redeveloped or improved.

Conclusion

We shouldn't be surprised that the Great War preoccupied much of the thinking behind society in the inter-war period because its scale and devestation was unlike anything seen before. For those who had lived through the experience, it was a defining moment in civilisation but the enormity of wartime events was not the defining experience of the younger generation nor of those whose loss had been so devestating that they wanted to forget the wartime horrors.

We shouldn't be surprised that the Great War preoccupied much of the thinking behind society in the inter-war period because its scale and devestation was unlike anything seen before. For those who had lived through the experience, it was a defining moment in civilisation but the enormity of wartime events was not the defining experience of the younger generation nor of those whose loss had been so devestating that they wanted to forget the wartime horrors.

References

[1] https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Empire-Day/

[2] Parish Magazine, May 1926 and August 1932

[3] Parish Magazine, May 1926

[4] Parish Magazine, March 1928

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 6 August 1921

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 1 October 1927

[7] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 September 1927

[1] https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Empire-Day/

[2] Parish Magazine, May 1926 and August 1932

[3] Parish Magazine, May 1926

[4] Parish Magazine, March 1928

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 6 August 1921

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 1 October 1927

[7] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 September 1927