|

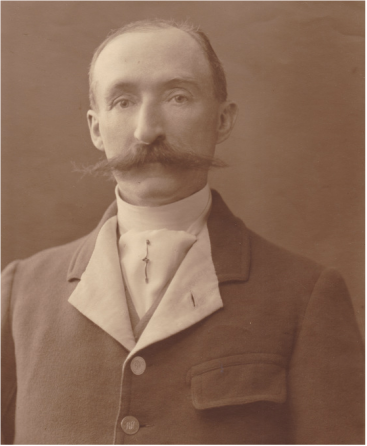

Memories of Ashley House Hugh Spencely September 2016 Photos and article courtesy Hugh Spencely Hugh Spencely records the details of his father, grandfather and earlier relatives, particularly their lives relevant to Box, between 1917 and 1927, when they lived at Ashley House, Shockerwick. Theirs was a style of life that has virtually disappeared: military service for employment, hunting for pleasure, and entertaining for recreation. It was reserved to a few wealthy people in late Victorian and Edwardian society. But they left their mark in Box. Left: Colonel Hugh le Despenser Spencely looking resplendent in Beaufort Hunt attire in about 1925. |

The Spencely family history at Box really starts with Peter Spencely, a man who never lived in the village. Peter was a convict. He was found guilty at Cambridge Assizes in July 1834 of housebreaking and sentenced to seven years transportation to New South Wales. He was released in 1842, the sentence only starting when he arrived there. He spent the rest of his life in poverty, dying in 1863 in New South Wales.

Peter's son, Castle, was born after he was transported. We think that the solicitor who represented Peter at his trial offered to help the unborn child. So he became a solicitors' writing clerk in Cambridge as a sixteen-year-old. The rest of his siblings were milliners and house painters. The name le Despenser is a total Victorian fabrication! I can find no connection with the Despensers.

Castle Spencely

Castle was eventually admitted as a solicitor to the Supreme Court, sponsored by local Cambridge solicitors. He then went up to Liverpool where he succeeded as a solicitor, was a freemason and joined the yeomanry. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, commanded the volunteer battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment and died in 1901. His son was Hugh le Despenser Spencely.

Hugh le Despenser Spencely followed in his father's footsteps in business and in the volunteer forces. He was a great horseman winning cups at the Bath Show. One of the important positions that Castle obtained was as agent to Lord Salisbury's estates in Merseyside. You may ask how he got that post much to the annoyance of the local solicitors. Probably it was due to his connections as a young man in Cambridge. There has been a suggestion that he had connections with Hatfield House, but that is unproven. Hugh le Despenser was an only child so he inherited all his father's wealth in 1901. That allowed him to retire in 1910 when he moved to a 2,000 acre estate in Herefordshire. The family moved from there following the tragic death of Mary aged seven from suspected appendicitis. She was a beautiful child, rather like her mother, my grandmother.

Below you can read Greville's memories which he recorded in about 1950. I do not think that my father knew anything about his grandfather's past. My father, Greville, was in the army like my grandfather. Greville was writing his entrance exams on Armistice Day 1918. He was in the Royal Artillery and on one occasion hacked back from Bulford Camp on Salisbury Plain to Ashley House. Horsemanship ran in the family. Greville resigned his commission in 1923 and went up to Liverpool University to read Architecture.

Peter's son, Castle, was born after he was transported. We think that the solicitor who represented Peter at his trial offered to help the unborn child. So he became a solicitors' writing clerk in Cambridge as a sixteen-year-old. The rest of his siblings were milliners and house painters. The name le Despenser is a total Victorian fabrication! I can find no connection with the Despensers.

Castle Spencely

Castle was eventually admitted as a solicitor to the Supreme Court, sponsored by local Cambridge solicitors. He then went up to Liverpool where he succeeded as a solicitor, was a freemason and joined the yeomanry. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, commanded the volunteer battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment and died in 1901. His son was Hugh le Despenser Spencely.

Hugh le Despenser Spencely followed in his father's footsteps in business and in the volunteer forces. He was a great horseman winning cups at the Bath Show. One of the important positions that Castle obtained was as agent to Lord Salisbury's estates in Merseyside. You may ask how he got that post much to the annoyance of the local solicitors. Probably it was due to his connections as a young man in Cambridge. There has been a suggestion that he had connections with Hatfield House, but that is unproven. Hugh le Despenser was an only child so he inherited all his father's wealth in 1901. That allowed him to retire in 1910 when he moved to a 2,000 acre estate in Herefordshire. The family moved from there following the tragic death of Mary aged seven from suspected appendicitis. She was a beautiful child, rather like her mother, my grandmother.

Below you can read Greville's memories which he recorded in about 1950. I do not think that my father knew anything about his grandfather's past. My father, Greville, was in the army like my grandfather. Greville was writing his entrance exams on Armistice Day 1918. He was in the Royal Artillery and on one occasion hacked back from Bulford Camp on Salisbury Plain to Ashley House. Horsemanship ran in the family. Greville resigned his commission in 1923 and went up to Liverpool University to read Architecture.

|

Greville Spencely's Memoirs

Childhood Writing against time can't have done one's handwriting any good. I didn't get many such punishments but I lost 143 marks for bad writing in the Army Exam; others lost between nil and 819 for this defect. However, I lost nothing for bad spelling, possibly because my vocabulary was limited by the lack of Latin and Greek. The biggest deduction in the Army Exam was 359 for T Price who became the shop's top horseman of his day, winning the Saddle. The photo right of Greville Spencely, aged 21, was taken on the pond below Ashley House, which was fed from the Bybrook. |

While I was at Harrow the family moved from Moor Court to Vennwood, a smaller house rented from Courage's (the brewers) near Marden about six miles north of Hereford. Vennwood afforded hunting and shooting, as did Moor Court, but I was now old enough to get real enjoyment from both. I remember the little parlour maid, Edith, who wore pince-nez (spectacles without side arms), and Milly, the house maid who had worked in the shell-filling factory near Hereford, and was stained yellow from the picric (acidic) fumes. I remember too picking mushrooms near the house as soon as the day was light enough and having them grilled for breakfast a few hours later.

From Vennwood my father, Hugh le D Spencely, took us trout fishing one year to the River Banwy where we stayed for a week or so at Carn Office Hotel on the A458 about ten miles east of Mallwyd.

From Vennwood my father, Hugh le D Spencely, took us trout fishing one year to the River Banwy where we stayed for a week or so at Carn Office Hotel on the A458 about ten miles east of Mallwyd.

Youth in Wales

In 1917 I was invited to a family friend's seaside house, Haulfryn, Abersoch, North Wales. I rode there either from Vennwood or from Ashley House (see later) on a two and three quarter horse-power, horizontal twin-cylinder, Douglas motor bike. As I was trying to slow down for the right angled turn at the village cross roads the exhaust valve's cable snapped and I ended on my right side, reaching Haulfryn late for dinner with lots of dust and dirt and some blood.

In 1917 I was invited to a family friend's seaside house, Haulfryn, Abersoch, North Wales. I rode there either from Vennwood or from Ashley House (see later) on a two and three quarter horse-power, horizontal twin-cylinder, Douglas motor bike. As I was trying to slow down for the right angled turn at the village cross roads the exhaust valve's cable snapped and I ended on my right side, reaching Haulfryn late for dinner with lots of dust and dirt and some blood.

We sometimes took part in tennis tournaments at Criccieth and Pwllheli where county players from Lancashire, Yorkshire and Cheshire played. Pwllheli's courts were so exposed to wind that their surrounding netting was almost useless. My brother, Jim, used to take me to the Chapel Island where we stalked rabbits with .22 rifles. There were scores of rabbits, black, brown and mottled, who shared the burrows with puffins. You might watch a rabbit enter a hole, wait with a rifle trained for it to emerge, only to see a puffin come out in its place - there are few rabbits now and the puffins are gone.

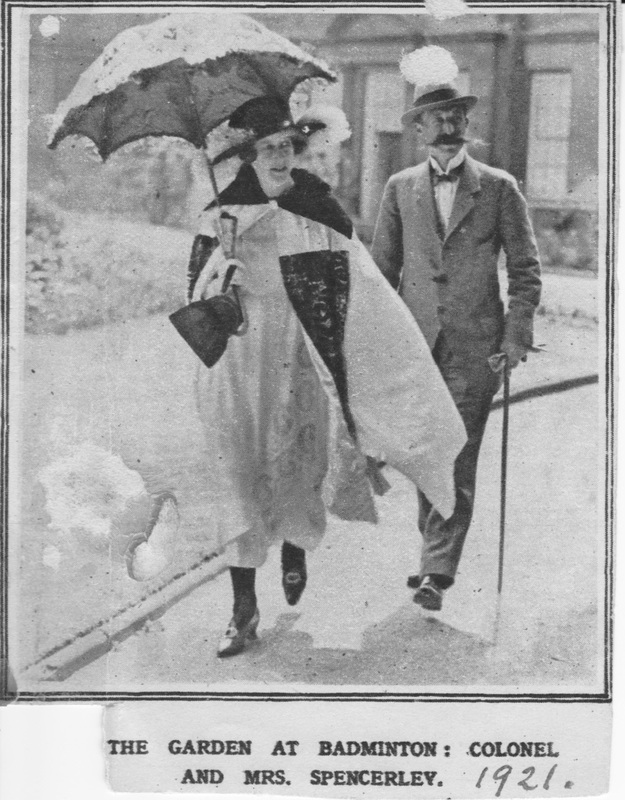

Left and centre: Hugh le D Spencely and Gladys on the occasion of their engagement; right: on an outing in 1921

Ashley House, 1917

In 1917 my family left Vennwood in Herefordshire for Box at the western edge of Wiltshire. My father had hoped to buy a country house with stables within a few miles of the Beaufort Kennels at Badminton. He got Ashley House, stone-built, one and a half miles west of Box, just above the main road (A4) and railway line between London and Bath. My mother liked the house because. among other things, it afforded a fine view down the valley towards Bath, but, as my father said, You can't live on a ...... view, and it was fourteen miles from the kennels.

Ashley House had a brick-walled kitchen garden with good fruit trees, a tennis and croquet lawn, a pond which provided water by means of a hydraulic ram which feeds water to the house (it took ten or fifteen gallons of water to raise one gallon to the house's storage tank), a lodge and a pair of cottages. These last stood in the meadow between the lane and the railway track where my father soon built wooden stables to enclose a yard. He bred chestnuts, sending mares to the King's Premium Stallions in the neighbourhood.

The house had pleasant rooms: a living room with bookshelves and a large open fire, a drawing room chiefly used for my mother's bridge parties, a dining room and a billiards room which provided a good dance floor when the table was dismantled. Jim was the family's expert at billiards which, owing to his asthma, suited him better than more active amusements. He later became champion snooker player at the Constitutional Club in Liverpool.

Upstairs Ashley House contained three double bedrooms, two singles, two bathrooms and staff bedrooms. Next to the dining room were the pantry, kitchen, servants hall and scullery. In a well-lit basement was a good lavatory, coat and boot room. Outside the kitchen was a double garage with a glass-roofed wash space and an engine room. The latter housed the acetylene plant where water dripped slowly onto calcium carbide to produce acetylene which gave a brilliant light. Digging out the resultant sludge was a filthy, smelly job in which I sometimes helped. This plant was later replaced by an oil engine and many electric batteries.

A few hundred yards up the hill, near the edge of Kingsdown, lay a twelve-acre meadow with a stone barn and stone byre, let to a neighbouring farmer, Mr Butt. The barn was later sold for conversion to a house (being replaced by a Dutch barn) and the public footpath diverted. The farmer's daughter still rents this piece of property, the only land belonging still to my father's trust.

In 1917 my family left Vennwood in Herefordshire for Box at the western edge of Wiltshire. My father had hoped to buy a country house with stables within a few miles of the Beaufort Kennels at Badminton. He got Ashley House, stone-built, one and a half miles west of Box, just above the main road (A4) and railway line between London and Bath. My mother liked the house because. among other things, it afforded a fine view down the valley towards Bath, but, as my father said, You can't live on a ...... view, and it was fourteen miles from the kennels.

Ashley House had a brick-walled kitchen garden with good fruit trees, a tennis and croquet lawn, a pond which provided water by means of a hydraulic ram which feeds water to the house (it took ten or fifteen gallons of water to raise one gallon to the house's storage tank), a lodge and a pair of cottages. These last stood in the meadow between the lane and the railway track where my father soon built wooden stables to enclose a yard. He bred chestnuts, sending mares to the King's Premium Stallions in the neighbourhood.

The house had pleasant rooms: a living room with bookshelves and a large open fire, a drawing room chiefly used for my mother's bridge parties, a dining room and a billiards room which provided a good dance floor when the table was dismantled. Jim was the family's expert at billiards which, owing to his asthma, suited him better than more active amusements. He later became champion snooker player at the Constitutional Club in Liverpool.

Upstairs Ashley House contained three double bedrooms, two singles, two bathrooms and staff bedrooms. Next to the dining room were the pantry, kitchen, servants hall and scullery. In a well-lit basement was a good lavatory, coat and boot room. Outside the kitchen was a double garage with a glass-roofed wash space and an engine room. The latter housed the acetylene plant where water dripped slowly onto calcium carbide to produce acetylene which gave a brilliant light. Digging out the resultant sludge was a filthy, smelly job in which I sometimes helped. This plant was later replaced by an oil engine and many electric batteries.

A few hundred yards up the hill, near the edge of Kingsdown, lay a twelve-acre meadow with a stone barn and stone byre, let to a neighbouring farmer, Mr Butt. The barn was later sold for conversion to a house (being replaced by a Dutch barn) and the public footpath diverted. The farmer's daughter still rents this piece of property, the only land belonging still to my father's trust.

Hunting and Hacking

There were usually five or six horses at home including a brood mare or two. They were looked after by Hole, and then Coward, helped by Hinton and a boy named Victor Painter, and were exercised daily.[1] Twice a week, if the hounds met within a reasonable distance, three horses would go there, the third being a second horse for my father.

There were usually five or six horses at home including a brood mare or two. They were looked after by Hole, and then Coward, helped by Hinton and a boy named Victor Painter, and were exercised daily.[1] Twice a week, if the hounds met within a reasonable distance, three horses would go there, the third being a second horse for my father.

Above left: Head groom, Mr Hole, in field above railway line; and above right: Groom Mr Hinton in 1921

The horse in both pictures above is Dutch Doll. Lieutenant Greville Spencely of 143 Battery, Royal Field Artillery, rode this horse back from Bulford Camp, Wiltshire, on his release from Reserve Duties during the coalminers' strike on 6 June 1921.

It was good exercise and pleasant on a dry day to be able to see the countryside over the hedges while jogging along ten or twelve miles partly perhaps along quiet lanes. The minor roads in 1917 were dusty or muddy, tarmac being reserved for the main roads. In dry weather a vehicle or a herd of cattle raised clouds such as you see in Western movies. Riding home ten or twelve miles after a day's hunting could be tiring, but one then learnt how to help one's horse and to be grateful to him for the day's fun. It was during such rides that my father must have regretted the house's distance from kennels; I know that I did. One of the pleasures of hunting was the joy of a hot bath after perhaps six or eight hours in the saddle.

When the Beaufort meets were too far away we attended those of the Avon Vale which were often more fun, chiefly because the Beaufort's popularity (and perhaps snob value, HRH the Prince of Wales sometimes being present) led to fields of three hundred horsemen and scores of cars following, which needed field masters to control the riders and wardens to prevent car drivers getting too far ahead. In such conditions, a good start when a fox was found was essential if you were to see anything of the run. To wait at the side of a covert, watching and listening to hounds working through it was exciting. There was usually a whip at the far end placed to see the fox break away. You could guess what was happening from the hounds' voices, which horses seemed to understand too.

Galloping and jumping were exhilarating, the fences were largely hedges, but in the stone country they were dry walls. These were safer than might be supposed because they stood on firm ground. The biggest risk would be a quarry on the far side but one usually remembered where those few hazards lay. Apart from an occasional fall, usually on soft ground, my only accident was to land on my head, protected by a top hat, on a stone wall.

Galloping and jumping were exhilarating, the fences were largely hedges, but in the stone country they were dry walls. These were safer than might be supposed because they stood on firm ground. The biggest risk would be a quarry on the far side but one usually remembered where those few hazards lay. Apart from an occasional fall, usually on soft ground, my only accident was to land on my head, protected by a top hat, on a stone wall.

Colonel Hugh le Despenser Spencely died in 1927 and was buried at Knowsley, Lancashire. Box village held a service simultaneously with the funeral. Rev George Foster gave the address "As he lived, so he died, a noble man". Colonel Spencely had caught a chill whilst out hunting, became unconscious and died two days later. The village was shocked to hear of his death and the church was packed out with over a hundred people including representatives from the local British Legion and the North Wiltshire Conservative Association.

The Spencely family sold Ashley House in 1934 and left Box. Greville and his wife moved back to the county in 1973; Greville died in 1983 and his wife ten years later. Hugh Spencely and his family moved to Wiltshire in 1967 living mostly in the Devizes area.

The Spencely family sold Ashley House in 1934 and left Box. Greville and his wife moved back to the county in 1973; Greville died in 1983 and his wife ten years later. Hugh Spencely and his family moved to Wiltshire in 1967 living mostly in the Devizes area.

Family Tree

1. Castle Spencely (1835 - 1901) was a solicitor, who lived in Knowsley, Lancashire from about 1868 until 1901. Wife Mary.

Child: Hugh le Despenser Spencely

2. Lieutenant Colonel Hugh le Despenser Spencely TD (1871 - 13 February 1927)

(Territorial Decoration was a military medal for long service in the Territorial Army) Wife Jessie Gladys (nee Thursfield)

Children: Hugh Greville Castle (usually called Greville) Spencely; James le Despenser (usually called Jim) Spencely. On Colonel Spencely's death Ashley House, the garden and grounds, lodge, garage, two cottages and farm buildings were valued for probate at £7,000.

Jessie Gladys remained in the house and in 1928 married her late husband's friend, Major Basil Owen Palmer MBE, late Border Regiment. The house continued in the family's ownership until Mrs Spencely and her new husband moved to Kensington, London in 1934. She died in 1977 aged 99. Major Palmer died in 1939. Jim went on to become a successful business man in Liverpool and was chairman of the Liverpool Conservative Club.[2]

3. Hugh Greville Castle Spencely (1900 - 1983)

Children included Hugh Spencely

1. Castle Spencely (1835 - 1901) was a solicitor, who lived in Knowsley, Lancashire from about 1868 until 1901. Wife Mary.

Child: Hugh le Despenser Spencely

2. Lieutenant Colonel Hugh le Despenser Spencely TD (1871 - 13 February 1927)

(Territorial Decoration was a military medal for long service in the Territorial Army) Wife Jessie Gladys (nee Thursfield)

Children: Hugh Greville Castle (usually called Greville) Spencely; James le Despenser (usually called Jim) Spencely. On Colonel Spencely's death Ashley House, the garden and grounds, lodge, garage, two cottages and farm buildings were valued for probate at £7,000.

Jessie Gladys remained in the house and in 1928 married her late husband's friend, Major Basil Owen Palmer MBE, late Border Regiment. The house continued in the family's ownership until Mrs Spencely and her new husband moved to Kensington, London in 1934. She died in 1977 aged 99. Major Palmer died in 1939. Jim went on to become a successful business man in Liverpool and was chairman of the Liverpool Conservative Club.[2]

3. Hugh Greville Castle Spencely (1900 - 1983)

Children included Hugh Spencely

References

[1] See Victor Painter's recollections, Kingsdown Memories, http://www.choghole.co.uk/victor/victormain.htm. He was employed by the Spencely family and after Hugh's grandmother left the house he was employed by the family as caretaker.

He lived in the lodge. Hugh has Greville's cheque book stubs showing payments made to him.

[2] More details of Ashley House and its residents are available at Ashley House.

[1] See Victor Painter's recollections, Kingsdown Memories, http://www.choghole.co.uk/victor/victormain.htm. He was employed by the Spencely family and after Hugh's grandmother left the house he was employed by the family as caretaker.

He lived in the lodge. Hugh has Greville's cheque book stubs showing payments made to him.

[2] More details of Ashley House and its residents are available at Ashley House.