Discovering Box Roman Villa Research and photos courtesy Kate Carless October 2020

The story of the excavations on the Roman Villa site is a long one. The site itself has been much disturbed as a medieval water-mill was built over it at the property now called The Wilderness and part of the west wing and the courtyard are still covered by the mill pond of that house. In fact, the medieval mill leat leading to the waterwheel cut through the pavements of two rooms (rooms 2 and 39). The pavements at the villa have been uncovered many times and left exposed to the weather before being recovered. Some of them have been wholly or partly destroyed by frost.

Rev George Mullins’ Discovery, 1831

The first reported discovery was in 1831 by the Rev George Mullins, who owned The Wilderness at the time. An unknown author commented in The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1831 that previous parts of a tessellated pavement had been unearthed in a garden belonging to Mr Mullins, adjoining the churchyard but no spot could be pointed out where the same might with certainty be found.[1] In making some additions to a very old building, the workmen, on sinking for a foundation, struck upon the mutilated remains of a tessellated pavement about two or three feet below the surface of the ground. It appeared to have been part of a large square, and the part now discovered was evidently one of its corners. It had a wide ornamental border of no remarkable beauty.[2] The article mentions reports of other pavements in the area, it is said that several beautiful tessellated pavements had formerly been found in the churchyard and gardens adjoining. On the island in the ornamental fishpond of The Wilderness very many Roman tesserae of different colours and sizes were found.

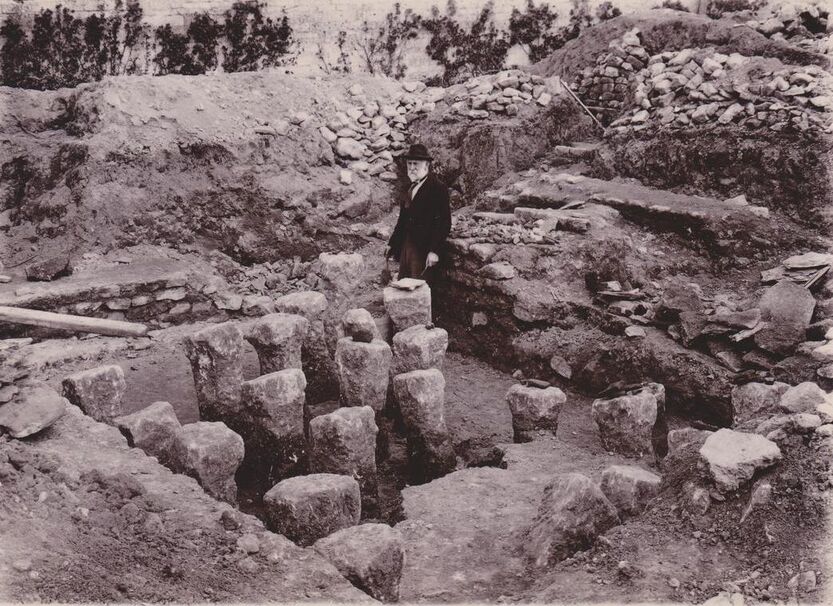

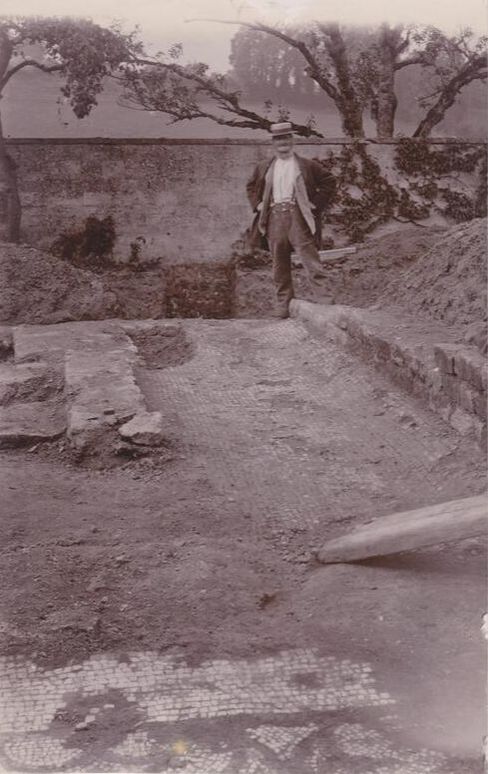

Two years later Rev Mullins gave details of more finds on his land, seven stone pillars leading from the original pavement to another mosaic forty-three yards north from the pavement alluded to.[3] Near the stones was an altar-like erection, consisting of several stones, and a piece of stone of a semi-circular shape about a foot across and eight inches thick. He goes on to list more finds: a tessellated pavement of blue stone with two red borders, a wall on the south side with several flues and a regular hypocaust. At a depth of four feet below the surface of the earth, he discovered a third pavement, nearly perfect, apparently forming a passage from some part of the building. It is nine feet wide, twenty-eight feet long … it evidently extended much further in both directions. He talks about the wall plaster which he discovered being imitations of Egyptian marble, with elegant coloured borderings. This was the first reported evidence of the Box Roman Villa.

Victorian Owners of The Wilderness

There are periodic reports of finds in the area in the Victorian period. Harold Brakspear summarised these in his later article. In 1860 H Syer Cuming reported:

My garden is full of Roman remains—tiles somewhat ornamented, but broken, bricks, tessellated pavement, fused iron, &c. I send all away to mend the roads; they are a perfect nuisance. We cannot put a spade into the ground without bringing up these impediments to vegetable growth. There is a bath quite perfect, in the centre of the (Vicarage?) garden. It has been opened, but is covered up; and a beautiful pavement runs all about. The bits I dug up were white and black, very coarse work.[4] Commenting on the discovery in 1892, the Rev EH Goddard was told that the finds came from a piece of ground adjoining The Wilderness.[5]

The first reported discovery was in 1831 by the Rev George Mullins, who owned The Wilderness at the time. An unknown author commented in The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1831 that previous parts of a tessellated pavement had been unearthed in a garden belonging to Mr Mullins, adjoining the churchyard but no spot could be pointed out where the same might with certainty be found.[1] In making some additions to a very old building, the workmen, on sinking for a foundation, struck upon the mutilated remains of a tessellated pavement about two or three feet below the surface of the ground. It appeared to have been part of a large square, and the part now discovered was evidently one of its corners. It had a wide ornamental border of no remarkable beauty.[2] The article mentions reports of other pavements in the area, it is said that several beautiful tessellated pavements had formerly been found in the churchyard and gardens adjoining. On the island in the ornamental fishpond of The Wilderness very many Roman tesserae of different colours and sizes were found.

Two years later Rev Mullins gave details of more finds on his land, seven stone pillars leading from the original pavement to another mosaic forty-three yards north from the pavement alluded to.[3] Near the stones was an altar-like erection, consisting of several stones, and a piece of stone of a semi-circular shape about a foot across and eight inches thick. He goes on to list more finds: a tessellated pavement of blue stone with two red borders, a wall on the south side with several flues and a regular hypocaust. At a depth of four feet below the surface of the earth, he discovered a third pavement, nearly perfect, apparently forming a passage from some part of the building. It is nine feet wide, twenty-eight feet long … it evidently extended much further in both directions. He talks about the wall plaster which he discovered being imitations of Egyptian marble, with elegant coloured borderings. This was the first reported evidence of the Box Roman Villa.

Victorian Owners of The Wilderness

There are periodic reports of finds in the area in the Victorian period. Harold Brakspear summarised these in his later article. In 1860 H Syer Cuming reported:

My garden is full of Roman remains—tiles somewhat ornamented, but broken, bricks, tessellated pavement, fused iron, &c. I send all away to mend the roads; they are a perfect nuisance. We cannot put a spade into the ground without bringing up these impediments to vegetable growth. There is a bath quite perfect, in the centre of the (Vicarage?) garden. It has been opened, but is covered up; and a beautiful pavement runs all about. The bits I dug up were white and black, very coarse work.[4] Commenting on the discovery in 1892, the Rev EH Goddard was told that the finds came from a piece of ground adjoining The Wilderness.[5]

|

He went on to publish a report on the bath house wing with a semi-circular, sunk space with a water course, the floor and the sides of this well are covered with tesserae.[6] The bath and the pavement had been removed and were for sale in Bath and he led a visit to Box in 1895 to look at a small patch of pavement which had been recently discovered immediately opposite the north side of the church tower, reporting that it is in a very disintegrated condition and will probably not long survive exposure.[7]

Building Valens Terrace, 1900 John Hardy bought a plot of land just north of the vicarage in 1897 to develop housing there (now called Valens Terrace and part of the garden of the Wilderness). He quickly uncovered more mosaic pavements and realising their importance, re-covered them and began asking around for professional archaeological help. Hardy made a tracing of the Mosaics at Roman Villa. It was much damaged by frost but the central portion, which consisted of a two-ringed knot pattern in red, white and blue, was lifted and framed and bought by Mr Falconer who later gave a fragment of a piece from another room to the Devizes Museum (no longer to be found there). To excavate the site in 1902-03 John Hardy commissioned Sir Harold Brakspear of Corsham, an eminent conservationist who had worked on Bath Abbey, Windsor Castle and Lacock Manor.[8] They uncovered a coin of the Roman Emperor Valens (364-378AD) and named the rank of houses after him. The wonderful photographs of the 1902-03 excavation were all taken by Sir Harold’s brother. |

Selwyn Hall Excavation, 1967-68

The last major excavation was in 1968-69 led by Dr Henry Hurst. The purpose was to establish a chronology for the main part of the site, and if possible, to fit into it the evidence from the previous season's work of a fourth century addition to the villa.[9]

Part of the north wing was re-examined and three main periods were distinguished: the courtyard in the first period; the second period involved the demolition much of the north wing, replaced by an apsidal-ended triclinium, 55 ft by 31 ft; and in the third period the triclinium was consolidated, its walls doubled and the external corridor replaced by two rooms. The report went on to say that the dating of the three periods is still far from certain.

The results of the excavation were published in 1987.[10] Evidence of a burnt layer of deposits was associated with copperworking remains and third and fourth-century pottery. The report confirms that Box had one of the richest collections of mosaic floors of any building in Roman Britain, with the remains of floors recorded in twenty of its rooms (equalling the total known for Woodchester).[11]

The last major excavation was in 1968-69 led by Dr Henry Hurst. The purpose was to establish a chronology for the main part of the site, and if possible, to fit into it the evidence from the previous season's work of a fourth century addition to the villa.[9]

Part of the north wing was re-examined and three main periods were distinguished: the courtyard in the first period; the second period involved the demolition much of the north wing, replaced by an apsidal-ended triclinium, 55 ft by 31 ft; and in the third period the triclinium was consolidated, its walls doubled and the external corridor replaced by two rooms. The report went on to say that the dating of the three periods is still far from certain.

The results of the excavation were published in 1987.[10] Evidence of a burnt layer of deposits was associated with copperworking remains and third and fourth-century pottery. The report confirms that Box had one of the richest collections of mosaic floors of any building in Roman Britain, with the remains of floors recorded in twenty of its rooms (equalling the total known for Woodchester).[11]

Box Roman Villa has never achieved the fame it deserves. This is partly because there is little evidence of it above-ground and no museum details apart from the model in the Box Library. It is also difficult to tell the full story of the villa as so much still remains to be discovered despite the efforts of the antiquarians and archaeologists mentioned in this article.

References

[1] Rev EH Goddard, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVI, 1892, p.405-08

[2] Brakspear thought the work was in The Old Parsonage House which burnt down in 1853, being replaced by Box House - see Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, 1904, p.236

[3] Reported by Rev EH Goddard in Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVI, 1892, p.405-08

[4] British Archaeological Journal 1860 (xvi, 340) reported by Harold Brakspear in Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, p.238

[5] Rev EH Goddard, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVI, 1892, p.405

[6] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVI, p.405-08

[7] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVIII, p.258-59

[8] Harold Brakspear, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, 1904, p.236-268

[9] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, 1969

[10] HR Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, Excavations at Box Roman Villa 1967-68, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, Vol.81, 1987, p.19-51

[11] HR Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, Excavations at Box Roman Villa 1967-68, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, Vol.81, 1987, p.22

[1] Rev EH Goddard, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVI, 1892, p.405-08

[2] Brakspear thought the work was in The Old Parsonage House which burnt down in 1853, being replaced by Box House - see Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, 1904, p.236

[3] Reported by Rev EH Goddard in Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVI, 1892, p.405-08

[4] British Archaeological Journal 1860 (xvi, 340) reported by Harold Brakspear in Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, p.238

[5] Rev EH Goddard, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVI, 1892, p.405

[6] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVI, p.405-08

[7] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXVIII, p.258-59

[8] Harold Brakspear, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, 1904, p.236-268

[9] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, 1969

[10] HR Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, Excavations at Box Roman Villa 1967-68, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, Vol.81, 1987, p.19-51

[11] HR Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, Excavations at Box Roman Villa 1967-68, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, Vol.81, 1987, p.22