History of Cuttings Mill Jane Browning March 2017

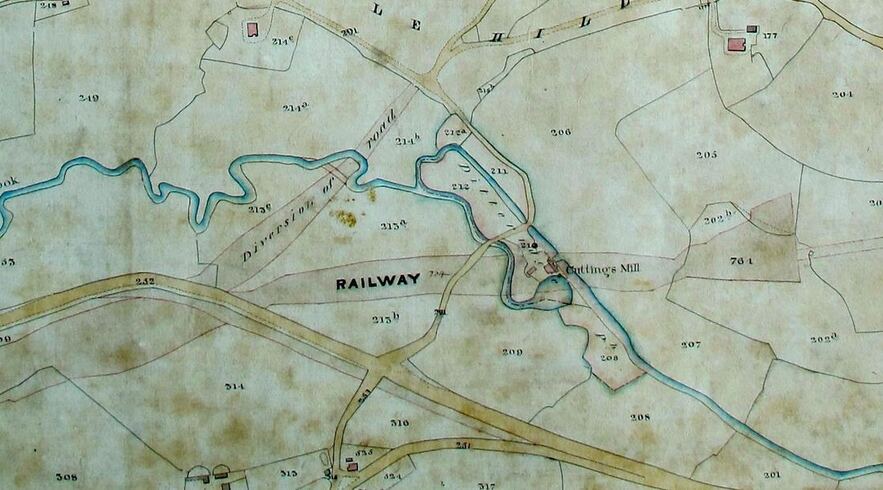

Part of 1838 map which shows the existing roads at Middlehill, the extent of Cuttings Mill, with its long leat and mill buildings, and the proposed route of the GWR through the Mill together with the new route of what is now known as the Avenue. (Courtesy of the Swindon and Wiltshire History Centre).

Many people are not aware that a mill formerly stood on Box Brook at Middlehill.[1] Cuttings Mill was nearer to Middlehill than the actual village of Box. It was on the part of the Brook adjacent to the Dirty Arch, which takes the public footpath from the Wilderness Bridge at Box, across the meadows to Middlehill, under the railway. The mill’s demise was precipitated by the coming of the Great Western Railway (GWR).

Very little is known of the mill itself. The Environment Agency published a booklet on the history of the By Brook which stated Nothing is known of this mill which was a casualty of the Great Western Railway, ending up under the embankment between Middlehill and Box Station.[2] There are a few remnants of stonework still visible in Box Brook at the site of Cuttings Mill and some ironwork, well embedded in the Brook’s bed, which could well have been part of the mill machinery. (Photos below courtesy Jane Browning).

Very little is known of the mill itself. The Environment Agency published a booklet on the history of the By Brook which stated Nothing is known of this mill which was a casualty of the Great Western Railway, ending up under the embankment between Middlehill and Box Station.[2] There are a few remnants of stonework still visible in Box Brook at the site of Cuttings Mill and some ironwork, well embedded in the Brook’s bed, which could well have been part of the mill machinery. (Photos below courtesy Jane Browning).

History

We know the mill existed in the Middle Ages as it was mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1086, which had been ordered by William the Conqueror to show what taxes had been owed during Edward the Confessor’s reign. Or, at least, half of it was mentioned as being within Ditteridge.

Warner holds DITTERIDGE from William (of Eu). Before 1066 it paid tax for 1 hide [120 acres] and 3 virgates of land [3 x 30 acres]. Land for 1 plough, which is there, in lordship;

2 villagers and 4 Cottagers.

½ mill which pays 5s; meadow, 7acres; pasture, 15 acres; underwood, 17acres.

Value 30s.

An Abbot of Malmesbury leased 1 hide of this land to Alstan.[3]

Warner also held the lordship of Chilton Cantelo, Somerset, under William of EU (1058-1096), who was a cousin of William the Conqueror and had fought in the Battle of Hastings. Alstan (1043-1087) held 55 lordships before the Norman Conquest.[4]

There is no mention of the other half of the mill in Domesday. As the mill would have straddled the Brook, the other half most probably came within the parish of Box which belonged to the King and therefore did not need to appear in the Domesday Book.

Watermills had appeared in England by the eight century, originally in eastern England and then spreading westward, though there were fewer water mills in the west.[5] The Domesday survey gives a precise count of England's water-powered flour mills: there were 5,624, or about one for every 300 inhabitants.[6] Each settlement would have had a mill owned by the Lord of the Manor to which all the Lord’s tenants had to take their corn to be milled.

We know the mill existed in the Middle Ages as it was mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1086, which had been ordered by William the Conqueror to show what taxes had been owed during Edward the Confessor’s reign. Or, at least, half of it was mentioned as being within Ditteridge.

Warner holds DITTERIDGE from William (of Eu). Before 1066 it paid tax for 1 hide [120 acres] and 3 virgates of land [3 x 30 acres]. Land for 1 plough, which is there, in lordship;

2 villagers and 4 Cottagers.

½ mill which pays 5s; meadow, 7acres; pasture, 15 acres; underwood, 17acres.

Value 30s.

An Abbot of Malmesbury leased 1 hide of this land to Alstan.[3]

Warner also held the lordship of Chilton Cantelo, Somerset, under William of EU (1058-1096), who was a cousin of William the Conqueror and had fought in the Battle of Hastings. Alstan (1043-1087) held 55 lordships before the Norman Conquest.[4]

There is no mention of the other half of the mill in Domesday. As the mill would have straddled the Brook, the other half most probably came within the parish of Box which belonged to the King and therefore did not need to appear in the Domesday Book.

Watermills had appeared in England by the eight century, originally in eastern England and then spreading westward, though there were fewer water mills in the west.[5] The Domesday survey gives a precise count of England's water-powered flour mills: there were 5,624, or about one for every 300 inhabitants.[6] Each settlement would have had a mill owned by the Lord of the Manor to which all the Lord’s tenants had to take their corn to be milled.

Geology

Box Brook flows into the River Avon at Bathford. In recent geological history, Box Brook was the headwaters of the Avon; drainage to the south, east, and north of its catchment being to the headwaters of the River Thames. Then a major shift along a fault line captured these waters for the River Avon, the sudden increase in water cut gorges through what is now Bristol and Bath exposing deep springs, including Bath's hot springs. This also caused Box Brook to run deeper and steeper, creating the valley it now runs through, and leaving it as a minor tributary of the larger river.[7]

Box Brook flows into the River Avon at Bathford. In recent geological history, Box Brook was the headwaters of the Avon; drainage to the south, east, and north of its catchment being to the headwaters of the River Thames. Then a major shift along a fault line captured these waters for the River Avon, the sudden increase in water cut gorges through what is now Bristol and Bath exposing deep springs, including Bath's hot springs. This also caused Box Brook to run deeper and steeper, creating the valley it now runs through, and leaving it as a minor tributary of the larger river.[7]

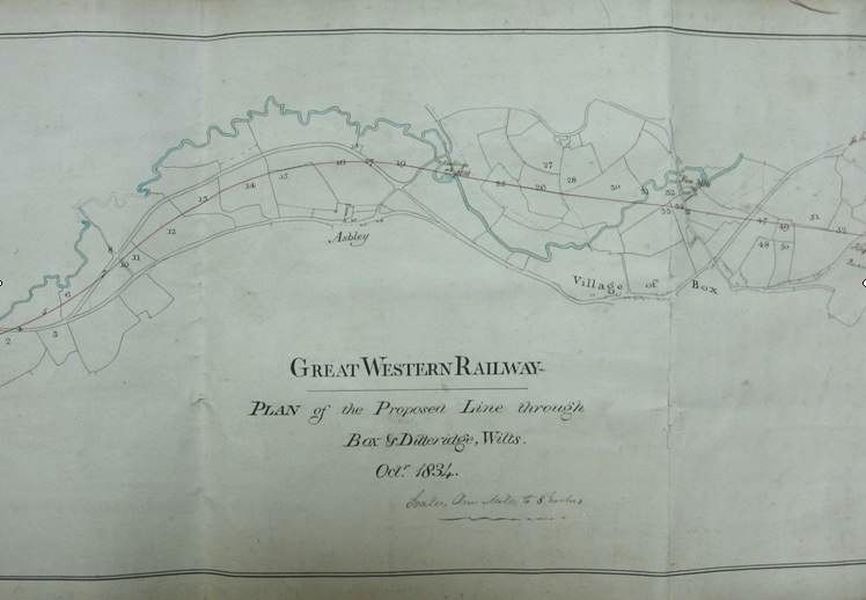

Part of 1834 map which gives an overview of the route of the GWR through Ditteridge and Box. Note the existing road layout at Ashley: there was a cross roads where the Northey Arms currently stands. The landowners in 1834 were Edward Richard Northey and John Iddolls.

(Courtesy of the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre).

(Courtesy of the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre).

The steepness of Box Brook, dropping 200 meters in 25 kilometers from its highest point to its confluence with the River Avon, has encouraged man to use the power of the Brook for milling since at least Roman times.[8]

The Brook has a mean flow rate of 57.25 cubic feet per second (1.621 cubic meters) as recorded at Middlehill near Box. There is evidence of at least twenty mills along the course of the Brook, although none are working today.[9]

Although mills were used for grinding corn in the Roman times, by the end of the 12th century in this area of Wiltshire many had been converted to fulling mills, cleansing and thickening wool. However, some mills reverted back to grinding corn after the Civil War due to the decline of the woollen industry.[10] The only evidence we have as to the raw material used at Cuttings Mill is in the indentures of the 18th century which refer to it as a grist mill (grinding grain into flour).

Although mills were used for grinding corn in the Roman times, by the end of the 12th century in this area of Wiltshire many had been converted to fulling mills, cleansing and thickening wool. However, some mills reverted back to grinding corn after the Civil War due to the decline of the woollen industry.[10] The only evidence we have as to the raw material used at Cuttings Mill is in the indentures of the 18th century which refer to it as a grist mill (grinding grain into flour).

Nearly 600 years after the Domesday Book, the 1630 Tithe map by Francis Allen shows the brook, mill and mill stream although it is not marked as a mill.

Part of the 1630 tithe map by Francis Allen. (Courtesy of the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre).

Millers

I have not been able to identify the dates of all the millers at Cuttings Mill, but the following is what I have managed to piece together from various documents and the parish registers of Box and Ditteridge.

The first mention of the millers by name that I could find is in a will dated 1 Oct 1725, by John Nutt, a miller of Box, though he lived another 20 plus years, dying in 1748. (For clarity, I shall call this person, John the elder) He left to his son, John Nutt of Cuttings Mill (John the younger), the great brass kettle, which he now has in his possession, and five shillings to buy him and his wife a pair of gloves. John the elder was able to leave a house, garden and orchard at Townsend to his daughter Ann, with daughter Jane having that part of the house which John lived in on the death of the wife of John (the elder).[11]

John Nutt (the younger) of Box had married Anne Trotman of Winsley on 29 June 1704 at Ditteridge church, with the marriage register noting he was a miller. The baptismal record for Box church showed his daughter Elizabeth Nutt was baptised on 26 Oct 1704. Again, John’s occupation was given as a millar [sic]. John and Ann had 4 more children who were baptised at Box, but no occupation was given. Whether John was still a miller when the later children were baptised can only be wondered at: the amount of information given in the parish registers was often down to the vicar of the time, but the period between 1700 and 1704 in the Box register invariably shows the occupation of the father.

However, John Nutt the younger was still alive in 1750 (he would have been about 68 years old) and a miller, as we can ascertain from the will of his sister, Ann Nutt, in which she left John £30.[12] As an aside, John’s (the elder) niece, Mary Nutt, daughter of his brother Thomas, was wife of George Mullins, the schoolmaster at Box for fifty years.[13]

Leases of Cuttings Mill

A lease dated 1 May 1775 referred to an earlier lease dated 3 June 1752. This 1752 lease showed that the mill house, outhouses and a watergrist mill was leased from William Northey of Compton Bassett to Robert Davis, late of Box, a blacksmith. This lease was a three-life lease, that is, for 99 years or until the death of the last of the three named people. At the end of each life, which could mean the actual death of the tenant or a change of circumstance for another reason, the incoming tenant bargained for a new lease of life. Customarily, a life was reckoned at 7 years, so a lease of three lives meant 21 yrs. This type of lease gave the tenant a reasonably secure tenure.[14] In this case the three named people were Robert Davis himself and his sons Arthur Lewis Davis and Robert Davis. [15]

The later 1775 lease was between William Northey (the son of the William Northey referred to in the 1752 indenture, who had died in 1770) to Edward Baldwin, late of Doddington, Gloucestershire, now of Box, yeoman. The lease included not only the mill house and mill, but also two quillets [small pieces of land] of meadow ground adjoining Middlehill about 20 perches including all outhouses etc, watercourses streams fishing millponds floodgates floodhatches etc. This time it was a four-life lease, the lives being Edward, his sons James Baldwin, aged 10 years, and Edward Baldwin aged 5 years, and John Brewer, aged about 8, the son of John Brewer of Sandy Lane. The fine, that is the payment to be made by the incoming tenant, was £20. The yearly rent was £1 and 3 shillings. The indenture states the mill had been in the possession of John Nutt, afterwards of the said Robert Davis (who died intestate in 1765) and then of Sarah Davis, his widow and now of Edward Baldwin.

From a survey carried out in 1793 and 1794 by Richard Richardson of Bath for William Northey, we know that Edward Baldwin was the miller. The extent of the land that he leased was 3 rods and 20 perches of which the 20 perches was an orchard additional to that valued with the mill. The total annual value was £20 10 shillings, with the rent being £1 and 3 shillings. It was held under a lifehold tenure.[16] Edward Baldwin died in 1799, leaving his estate, which included Cuttings Mill, equally between his children, with maintenance for his wife. Two of his children had pre-deceased him and, as they each had a child, these two (grand)children were included in the division of his estate.[17]

From 1813 the Ditteridge baptism register included the occupation and abode of the parents. From this we learn that John Salway was a miller and was married to Elizabeth. Elizabeth’s burial entry in the Ditteridge register on 10 March 1826 showed that she lived at Cuttings Mill and died at age 46. So we can take it that John Salway was the miller at Cuttings Mill at least between 1813 and 1826. John and Elizabeth had five children baptized between 1813 and 1828: John in 1813, Charlotte in 1816; Caroline in 1818, James Baldwin in 1819 (who died 1824), Thomas in 1820 and William in 1828, though he was born in 1822. There were four earlier baptisms, between 1807 and 1811 but as the baptism register was not then annotated, we cannot say that John Salway was the miller at that time.

I have not been able to identify the dates of all the millers at Cuttings Mill, but the following is what I have managed to piece together from various documents and the parish registers of Box and Ditteridge.

The first mention of the millers by name that I could find is in a will dated 1 Oct 1725, by John Nutt, a miller of Box, though he lived another 20 plus years, dying in 1748. (For clarity, I shall call this person, John the elder) He left to his son, John Nutt of Cuttings Mill (John the younger), the great brass kettle, which he now has in his possession, and five shillings to buy him and his wife a pair of gloves. John the elder was able to leave a house, garden and orchard at Townsend to his daughter Ann, with daughter Jane having that part of the house which John lived in on the death of the wife of John (the elder).[11]

John Nutt (the younger) of Box had married Anne Trotman of Winsley on 29 June 1704 at Ditteridge church, with the marriage register noting he was a miller. The baptismal record for Box church showed his daughter Elizabeth Nutt was baptised on 26 Oct 1704. Again, John’s occupation was given as a millar [sic]. John and Ann had 4 more children who were baptised at Box, but no occupation was given. Whether John was still a miller when the later children were baptised can only be wondered at: the amount of information given in the parish registers was often down to the vicar of the time, but the period between 1700 and 1704 in the Box register invariably shows the occupation of the father.

However, John Nutt the younger was still alive in 1750 (he would have been about 68 years old) and a miller, as we can ascertain from the will of his sister, Ann Nutt, in which she left John £30.[12] As an aside, John’s (the elder) niece, Mary Nutt, daughter of his brother Thomas, was wife of George Mullins, the schoolmaster at Box for fifty years.[13]

Leases of Cuttings Mill

A lease dated 1 May 1775 referred to an earlier lease dated 3 June 1752. This 1752 lease showed that the mill house, outhouses and a watergrist mill was leased from William Northey of Compton Bassett to Robert Davis, late of Box, a blacksmith. This lease was a three-life lease, that is, for 99 years or until the death of the last of the three named people. At the end of each life, which could mean the actual death of the tenant or a change of circumstance for another reason, the incoming tenant bargained for a new lease of life. Customarily, a life was reckoned at 7 years, so a lease of three lives meant 21 yrs. This type of lease gave the tenant a reasonably secure tenure.[14] In this case the three named people were Robert Davis himself and his sons Arthur Lewis Davis and Robert Davis. [15]

The later 1775 lease was between William Northey (the son of the William Northey referred to in the 1752 indenture, who had died in 1770) to Edward Baldwin, late of Doddington, Gloucestershire, now of Box, yeoman. The lease included not only the mill house and mill, but also two quillets [small pieces of land] of meadow ground adjoining Middlehill about 20 perches including all outhouses etc, watercourses streams fishing millponds floodgates floodhatches etc. This time it was a four-life lease, the lives being Edward, his sons James Baldwin, aged 10 years, and Edward Baldwin aged 5 years, and John Brewer, aged about 8, the son of John Brewer of Sandy Lane. The fine, that is the payment to be made by the incoming tenant, was £20. The yearly rent was £1 and 3 shillings. The indenture states the mill had been in the possession of John Nutt, afterwards of the said Robert Davis (who died intestate in 1765) and then of Sarah Davis, his widow and now of Edward Baldwin.

From a survey carried out in 1793 and 1794 by Richard Richardson of Bath for William Northey, we know that Edward Baldwin was the miller. The extent of the land that he leased was 3 rods and 20 perches of which the 20 perches was an orchard additional to that valued with the mill. The total annual value was £20 10 shillings, with the rent being £1 and 3 shillings. It was held under a lifehold tenure.[16] Edward Baldwin died in 1799, leaving his estate, which included Cuttings Mill, equally between his children, with maintenance for his wife. Two of his children had pre-deceased him and, as they each had a child, these two (grand)children were included in the division of his estate.[17]

From 1813 the Ditteridge baptism register included the occupation and abode of the parents. From this we learn that John Salway was a miller and was married to Elizabeth. Elizabeth’s burial entry in the Ditteridge register on 10 March 1826 showed that she lived at Cuttings Mill and died at age 46. So we can take it that John Salway was the miller at Cuttings Mill at least between 1813 and 1826. John and Elizabeth had five children baptized between 1813 and 1828: John in 1813, Charlotte in 1816; Caroline in 1818, James Baldwin in 1819 (who died 1824), Thomas in 1820 and William in 1828, though he was born in 1822. There were four earlier baptisms, between 1807 and 1811 but as the baptism register was not then annotated, we cannot say that John Salway was the miller at that time.

Evidence of the Mill in Box Brook with remnants of walls and many large blocks of stone in the bed, downstream from the Mill site (Courtesy Jane Browning).

End of Cuttings Mill

We then come to an Emma Hobbs of Cuttings Mill who was buried on 27 Oct 1831 aged 13 months at Ditteridge. At her baptism at Ditteridge in 1830 her father George was a farmer at Alcombe. By 1832 George Hobbs was at Cuttings Mill, as shown in the baptism register for his son Otto, but no occupation was given. By 1841 he was a farmer, and his capacity at Cuttings Mill is not known.

The Ditteridge baptism register indicated that William James was the miller at Cuttings Mill in the 1830s – he and his wife, Mary Ann, had three children baptised at Ditteridge: Sophia in 1833 (died 1835), Hellen in 1835 and Matilda in 1837. A survey of Ditteridge in 1839, made by the order of the Board of Guardians of the Chippenham Union [the local poor house] by Cotterells and Cooper, Bath, mentioned the garden at Cuttings Mill. The mill garden was occupied by William James, but owned by Thomas Andrews. Thomas Andrews appears to have been a limeburner at Weston in 1820 and by 1833 was a farmer. The mill itself was owned by the GWR.[18]

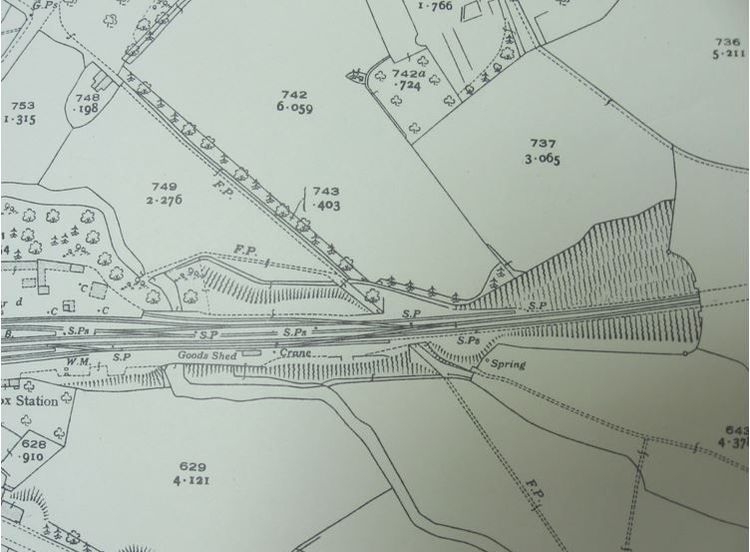

As indicated at the beginning of this article, the mill itself was demolished to make way for the GWR. The 1834 map below shows the extent of the sidings at Box Station where they overlay Cuttings Mill, with the new route of Box Brook. The course of the Brook had to be altered for the railway and the mill pond and leat were chosen to be the new course of the brook, no doubt so that the flow of water could be controlled during the construction of the embankment between the station and Middle Hill tunnel.[19]

We then come to an Emma Hobbs of Cuttings Mill who was buried on 27 Oct 1831 aged 13 months at Ditteridge. At her baptism at Ditteridge in 1830 her father George was a farmer at Alcombe. By 1832 George Hobbs was at Cuttings Mill, as shown in the baptism register for his son Otto, but no occupation was given. By 1841 he was a farmer, and his capacity at Cuttings Mill is not known.

The Ditteridge baptism register indicated that William James was the miller at Cuttings Mill in the 1830s – he and his wife, Mary Ann, had three children baptised at Ditteridge: Sophia in 1833 (died 1835), Hellen in 1835 and Matilda in 1837. A survey of Ditteridge in 1839, made by the order of the Board of Guardians of the Chippenham Union [the local poor house] by Cotterells and Cooper, Bath, mentioned the garden at Cuttings Mill. The mill garden was occupied by William James, but owned by Thomas Andrews. Thomas Andrews appears to have been a limeburner at Weston in 1820 and by 1833 was a farmer. The mill itself was owned by the GWR.[18]

As indicated at the beginning of this article, the mill itself was demolished to make way for the GWR. The 1834 map below shows the extent of the sidings at Box Station where they overlay Cuttings Mill, with the new route of Box Brook. The course of the Brook had to be altered for the railway and the mill pond and leat were chosen to be the new course of the brook, no doubt so that the flow of water could be controlled during the construction of the embankment between the station and Middle Hill tunnel.[19]

1834 map of the railway sidings at Box Station which overlay Cuttings Mill (Courtesy Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre).

Timeline

1086 In Domesday book

1704 John Nutt, miller, married Ann Trotman at Ditteridge

1704 John’s daughter Elizabeth Nutt baptised at Box Church

1748 John Nutt the elder, miller, died

Formerly in possession of John Nutt, Robert Davis and Sarah Davis, his widow.

1750 John Nutt, miller (from Ann Nutt’s will)

1752 Robert Davis leases grist mill for 4 score and nineteen years from William Northey

1775 Mill leased to Edward Baldwin by Wm Northey (Robert Davis had died)

1793-4 Edward Baldwin leasing Mill, Homestead and two orchards at Cuttings Mill

1799 Edward Baldwin died. His estate, including Cuttings Mill, to be split equally between his children (see will) James Broom,

his son-in-law was executor

1813- 1828 baptism of children shows their father John Salway was a miller

1830s William James was miller

1839 GWR owned the mill. Mill garden owned by Thomas Andrews and occupied by William James

1086 In Domesday book

1704 John Nutt, miller, married Ann Trotman at Ditteridge

1704 John’s daughter Elizabeth Nutt baptised at Box Church

1748 John Nutt the elder, miller, died

Formerly in possession of John Nutt, Robert Davis and Sarah Davis, his widow.

1750 John Nutt, miller (from Ann Nutt’s will)

1752 Robert Davis leases grist mill for 4 score and nineteen years from William Northey

1775 Mill leased to Edward Baldwin by Wm Northey (Robert Davis had died)

1793-4 Edward Baldwin leasing Mill, Homestead and two orchards at Cuttings Mill

1799 Edward Baldwin died. His estate, including Cuttings Mill, to be split equally between his children (see will) James Broom,

his son-in-law was executor

1813- 1828 baptism of children shows their father John Salway was a miller

1830s William James was miller

1839 GWR owned the mill. Mill garden owned by Thomas Andrews and occupied by William James

References

[1] I shall refer to it as Box Brook, rather than the Bybrook by which it is known today, as that is what it has always been known by my family who milled at both Drewetts and Box Mills. John Britton in his book of 1825 entitled The Beauties of Wiltshire also called it Box Brook, see Box in 1830.

[2] Ken Tatem, A History of the By Brook, published by the Environment Agency, p.7

[3] Caroline and Frank Thorn (editors), Domesday Book: Wiltshire, 1979, Phillimore Chichester, p.71d

[4] Jane Cox, The Norman Conquest of Box, Wiltshire – Our Medieval Lords, 2016

[5] WG Hoskins, The Making of the English Landscape, 1988, Guild Publishing, p.73

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gristmill accessed 18 Jan 2016

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bybrook_River accessed 18 Jan 2016

[8] Ken Tatem, A History of the By Brook, p.4

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bybrook_River accessed 18 Jan 2016

[10] Ken Tatem, A History of the By Brook, p.4

[11] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File P3/N/237

[12] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre FileP3/N/252

[13] See George Mullins article

[14] Jonathan Brown, Tracing Your Rural Ancestors, 2011, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, p.38

[15] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File 220/9

[16] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File 378/1

[17] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File P3/B/1764

[18] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File 220/14

[19] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2 of British Railway Journal, p.133

[1] I shall refer to it as Box Brook, rather than the Bybrook by which it is known today, as that is what it has always been known by my family who milled at both Drewetts and Box Mills. John Britton in his book of 1825 entitled The Beauties of Wiltshire also called it Box Brook, see Box in 1830.

[2] Ken Tatem, A History of the By Brook, published by the Environment Agency, p.7

[3] Caroline and Frank Thorn (editors), Domesday Book: Wiltshire, 1979, Phillimore Chichester, p.71d

[4] Jane Cox, The Norman Conquest of Box, Wiltshire – Our Medieval Lords, 2016

[5] WG Hoskins, The Making of the English Landscape, 1988, Guild Publishing, p.73

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gristmill accessed 18 Jan 2016

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bybrook_River accessed 18 Jan 2016

[8] Ken Tatem, A History of the By Brook, p.4

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bybrook_River accessed 18 Jan 2016

[10] Ken Tatem, A History of the By Brook, p.4

[11] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File P3/N/237

[12] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre FileP3/N/252

[13] See George Mullins article

[14] Jonathan Brown, Tracing Your Rural Ancestors, 2011, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, p.38

[15] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File 220/9

[16] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File 378/1

[17] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File P3/B/1764

[18] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre File 220/14

[19] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2 of British Railway Journal, p.133